Center for Texas Public History Department of History Texas State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Texas § City of Brownsville § County of Cameron §

THE STATE OF TEXAS § CITY OF BROWNSVILLE § COUNTY OF CAMERON § Derek Benavides, Secretary Abraham Galonsky, Commissioner Troy Whittemore, Commissioner Aaron Rendon, Commissioner Ruben O’Bell, Commissioner Vanessa Castillo, Commissioner Ronald Mills, Chairman NOTICE OF A PUBLIC MEETING OF THE PLANNING AND ZONING COMMISSION OF THE CITY OF BROWNSVILLE TELECONFERENCE OPEN MEETING Pursuant to Chapter 551, Title 5 of the Texas Government Code, the Texas Open Meetings Act, notice is hereby given that the Planning and Zoning Commission of the City of Brownsville, Texas, has scheduled a Regular Meeting on Thursday, April 1, 2021 at 5:30 P.M. via Zoom Teleconference Meeting by logging on at: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81044265311?pwd=YXZJcWhpdWNvbXNxYjZ5NzZEWUgrZz09 Meeting ID: 810 4426 5311 Passcode: 659924 This Notice and Meeting Agenda, are posted online at: http://www.cob.us/AgendaCenter The members of the public wishing to participate in the meeting hosted through WebEx Teleconference can join at the following numbers: One tap mobile: +13462487799,,81044265311#,,,,*659924# US (Houston) +16699006833,,81044265311#,,,,*659924# US (San Jose) Or Telephone: Dial by your location: +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) +1 929 205 6099 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Washington DC) Meeting ID: 810 4426 5311 Passcode: 659924 Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kbgc6tOoRF Members of the public who submitted a “Public Comment Form” will be permitted to offer public comments as provided by the agenda and as permitted by the presiding officer during the meeting. -

Southern Illinois University Welcomed Home One of Its All-Time Greats, Naming Bryan Mullins As the School’S 14Th Men’S Basketball Head Coach on March 20, 2019

@SIU_BASKETBALL // #SALUKIS // SIUSALUKIS.COM Contents 2019-20 schedule INTRO TO SALUKI BASKETBALL Date Note Opponent Location Time Watch Schedule/Roster ..................................1 Nov. 5 Illinois Wesleyan Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN3 Banterra Center ............................... 2-9 Sunshine Slam 1967 NIT Championship ............. 10-11 Nov. 8 vs. UTSA Kissimmee, Fla. 6:30 p.m. CT FloHoops 1977 Sweet 16 .................................... 12 Nov. 9 vs. Delaware Kissimmee, Fla. 2 p.m. CT FloHoops Rich Herrin Era ................................... 13 Nov. 10 vs. Oakland Kissimmee, Fla. 12 p.m. CT FloHoops 2002 Sweet 16 ..............................14-15 Nov. 16 ^ San Francisco Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN3 Six-Straight NCAAs ......................16-17 Nov. 19 at Murray State Murray, Ky. 7 p.m. ESPN+ 2007 Sweet 16 ..............................18-19 Nov. 26 NC Central Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN+ Salukis in the NBA ....................... 20-21 Dec. 1 at Saint Louis St. Louis, Mo. 3 p.m. Fox Sports Midwest Academics / Strength ................22-23 Dec. 4 Norfolk State Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN+ Dec. 7 at Southern Miss Hattiesburg, Miss. TBD TBD 2019-20 PREVIEW Dec. 15 at Missouri Columbia, Mo. 3 p.m. SEC Network Season Outlook .................................25 Dec. 18 Hampton Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. ESPN+ Player Bios (Alphabetical) ........ 26-39 Dec. 21 Southeast Missouri Carbondale, Ill. 3 p.m. ESPN3 Head Coach Bryan Mullins .......40-41 Dec. 30 * at Indiana State Terre Haute, Ind. 7 p.m. MVC TV Network Coaching & Support Staff ........ 42-46 Jan. 4 * Illinois State Carbondale, Ill. 3 p.m. ESPN3 Quick Facts .........................................47 Jan. 7 * Valparaiso Carbondale, Ill. 7 p.m. -

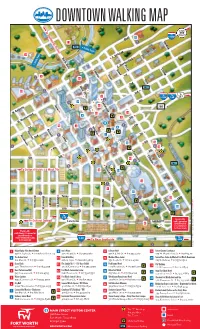

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

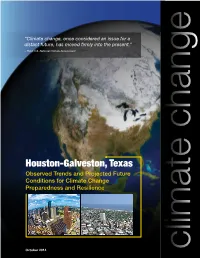

Houston-Galveston Exercise Division

About the National Exercise Program Climate About the National Exercise Program Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional The Third U.S. National Climate Assessment, Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional The Third U.S. National Climate Assessment, Workshops released in May 2014, assesses the science of climate Workshops released in May 2014, assesses the science of climate change and its impacts across the United States, now change and its impacts across the United States, now The Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional Workshops are an element of the the settingThe Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional Workshops are an element of the the setting and throughout this century. It integrates findings of and throughout this century. It integrates findings of overarching Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Exercise Series sponsored by the White overarching Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Exercise Series sponsored by the White the U.S. Global Change Research Program with the the U.S. Global Change Research Program with the House National Security Council Staff, Council on Environmental Quality, and Office of Science House National Security Council Staff, Council on Environmental Quality, and Office of Science results of research and observations from across the results of research and observations from across the and Technology Policy, in collaboration with the National Exercise Division. The workshops and Technology Policy, in collaboration with the NationalThe Houston-Galveston Exercise -

Total Population

HOW WE COMPARE Diversity . Education . Employment . Housing . Income . Transportation ____________________________________________ Houston’s Comparison with Major U.S. Cities April 2009 CITY OF HOUSTON Planning and Development Department Public Policy Division CITY OF HOUSTON Planning and Development Dept. Public Policy Division April 2009 HOW WE COMPARE Diversity . Education . Employment . Housing . Income . Transportation ____________________________________________ Table of Contents • Population o Figure 1: Total Population o Figure 2: Population Change o Figure 3: Male and Female Population o Figure 4: Population by Race\Ethnicity o Figure 5: Age 18 Years and Over o Figure 6: Age 65 Years and Over o Figure 7: Native and Foreign born • Households o Figure 8: Total Households o Figure 9: Family and Non-Family Households o Figure 10: Married Couple Family o Figure 11: Female Householder – No husband Present o Figure 12: Average Household Size o Figure 13: Marital Status • Education o Figure 14: Educational Attainment o Figure 15: High School Graduates o Figure 16: Graduate and Professional • Income & Poverty o Figure 17: Median Household Income o Figure 18: Individuals Below Poverty Level o Figure 19: Families Below Poverty Level • Employment o Figure 20: Not in Labor Force o Figure 21: Employment in Educational, Health & Services o Figure 22: Unemployment Rate for Cities o Figure 23: Unemployment Rate for Metro Areas o Figure 24: Class of Workers CITY OF HOUSTON Planning and Development Dept. Public Policy Division April 2009 HOW WE -

District 16 District 142 Brandon Creighton Harold Dutton Room EXT E1.412 Room CAP 3N.5 P.O

Elected Officials in District E Texas House District 16 District 142 Brandon Creighton Harold Dutton Room EXT E1.412 Room CAP 3N.5 P.O. Box 2910 P.O. Box 2910 Austin, TX 78768 Austin, TX 78768 (512) 463-0726 (512) 463-0510 (512) 463-8428 Fax (512) 463-8333 Fax 326 ½ N. Main St. 8799 N. Loop East Suite 110 Suite 305 Conroe, TX 77301 Houston, TX 77029 (936) 539-0028 (713) 692-9192 (936) 539-0068 Fax (713) 692-6791 Fax District 127 District 143 Joe Crab Ana Hernandez Room 1W.5, Capitol Building Room E1.220, Capitol Extension Austin, TX 78701 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 463-0520 (512) 463-0614 (512) 463-5896 Fax 1233 Mercury Drive 1110 Kingwood Drive, #200 Houston, TX 77029 Kingwood, TX 77339 (713) 675-8596 (281) 359-1270 (713) 675-8599 Fax (281) 359-1272 Fax District 144 District 129 Ken Legler John Davis Room E2.304, Capitol Extension Room 4S.4, Capitol Building Austin, TX 78701 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 463-0460 (512) 463-0734 (512) 463-0763 Fax (512) 479-6955 Fax 1109 Fairmont Parkway 1350 NASA Pkwy, #212 Pasadena, 77504 Houston, TX 77058 (281) 487-8818 (281) 333-1350 (713) 944-1084 (281) 335-9101 Fax District 145 District 141 Carol Alvarado Senfronia Thompson Room EXT E2.820 Room CAP 3S.06 P.O. Box 2910 P.O. Box 2910 Austin, TX 78768 Austin, TX 78768 (512) 463-0732 (512) 463-0720 (512) 463-4781 Fax (512) 463-6306 Fax 8145 Park Place, Suite 100 10527 Homestead Road Houston, TX 77017 Houston, TX (713) 633-3390 (713) 649-6563 (713) 649-6454 Fax Elected Officials in District E Texas Senate District 147 2205 Clinton Dr. -

Parkway Plaza 5855 Eastex Freeway Beaumont, Texas 77706

RETAIL PROPERTY FOR LEASE PARKWAY PLAZA 5855 EASTEX FREEWAY BEAUMONT, TEXAS 77706 MICHAEL FERTITTA, PRINCIPAL | 409.791.6453 | [email protected] CRAIG GARANSUAY, CEO | 210.667.6466 | [email protected] No warranty expressed or implied has been made as to the accuracy of this information, no liability assumed for errors or omissions. RETAIL PROPERTY FOR LEASE PARKWAY PLAZA 5855 EASTEX FREEWAY BEAUMONT, TEXAS 77706 PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Parkway Plaza is located on Eastex Freeway across from Parkdale Mall. Parkway Plaza is part of the main trade area servicing the Beaumont-Port Arthur Metropolitan area and is currently experiencing substantial growth with approximately 75,000 SF of new to market retail and dining being developed. Beaumont is located in Southeast Texas on the Neches River about 90 miles East of Houston. Beaumont is the county seat of Jefferson County with a population of around 120,000. This trade area serves the Beaumont–Port Arthur Metropolitan Area with a population of approximately 405,000 people. The city is home to Lamar University and the Lamar Institute of Technology which educates around 19,000 students in total. The area also boasts one of the largest deep- water ports in the country, two large hospitals and medical campus. Beaumont is well known for its refineries and industrial opportunities as well as the South Texas State Fair and Rodeo which is the second largest State Fair with approximately 500,000 visitors annually. SIZE AVAILABLE 45,854 SF (Approx. 216’ x 212’) divisible PRICE Call broker for pricing TRIPLE NET CHARGES Call broker for pricing TRAFFIC COUNTS Eastex Freeway: 80,192 VPD | Dowlen Rd: 8,832 VPD KEY TENANTS Best Buy, ALDI, Party City, FedEx, IHOP and Fuzzy’s Tacos AREA RETAILERS Target, Walmart, Burlington, Kohl’s, Lowes Home Improvement, Kroger, Academy, Conn’s Home Plus, Ross Dress for Less, PetSmart, Petco and many more. -

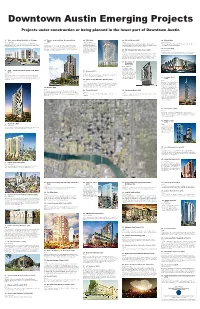

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects Projects under construction or being planned in the lower part of Downtown Austin 1. 7th & Lamar (North Block, Phase II) (C2g) 11. Thomas C. Green Water Treatment Plant 20. 7Rio (R60) 28. 5th and Brazos (C54) 39. Eleven (R86) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ (C56) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ Planned 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ &RQVWUXFWLRQLVXQGHUZD\DWWKHVLWHRIWKHIRUPHU.$6(.9(7UDGLR Planned &RQVWUXFWLRQVWDUWHGLQ0D\ $QH[LVWLQJYDOHWSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLOOEHWRUQGRZQDQGUHSODFHGE\DQ :RUNFRQWLQXHVRQWKLVXQLWPXOWLIDPLO\SURMHFWRQ(WK6WUHHW VWXGLREXLOGLQJIRUWKHFRQVWUXFWLRQRIDQHZSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWK 7KH*UHHQVLWHZLOOFRQVLVWRIVHYHUDOEXLOGLQJVXSWRVWRULHVWDOO RQWKLVXQLWDSDUWPHQW HLJKWVWRU\SDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWKVSDFHV7KDWJDUDJHVWUXFWXUHZLOODOVR RYHUORRNLQJ,DQGGRZQWRZQ$XVWLQ VIRIJURXQGÀRRUUHWDLO ,QFOXGLQJ%ORFN VHHEHORZ WKHSURMHFWZLOOKDYHPLOOLRQ WRZHUDW:WK6WUHHWDQG5LR LQFOXGHVTXDUHIHHWRIVWUHHWOHYHOUHWDLOVSDFH VTXDUHIHHWRIGHYHORSPHQWLQFOXGLQJDSDUWPHQWVVTIWRI *UDQGHE\&DOLIRUQLDEDVHG RI¿FHVSDFHDURRPKRWHODQGVTIWRIUHWDLO PRVWDORQJDQ GHYHORSPHQWFRPSDQ\&:6 40. Corazon (R66) H[WHQVLRQRIWKHQG6WUHHW'LVWULFW 7KHSURMHFWZDVGHVLJQHG 29. 5th & Brazos Mixed-Use Tower (C89) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ E\ORFDODUFKLWHFWXUDO¿UP Planned 5KRGH3DUWQHUV &\SUHVV5HDO(VWDWH$GYLVHUVLVEXLOGLQJ&RUD]RQDYHUWLFDOPL[HGXVH $VN\VFUDSHURIXSWRVWRULHVZLWKKRWHOURRPVDQGUHVLGHQFHVDW(DVW SURMHFWWKDWZLOOLQFOXGHUHVLGHQWLDOXQLWVUHWDLODQGDUHVWDXUDQW )LIWKDQG%UD]RVVWUHHWVGRZQWRZQ7KHWRZHUFRXOGLQFOXGHRQHRUWZR KRWHOVDQGPRUHWKDQKRXVLQJXQLWVPRVWOLNHO\DSDUWPHQWV&KLFDJR EDVHG0DJHOODQ'HYHORSPHQW*URXSZRXOGGHYHORSWKHSURMHFWZLWK :DQ[LDQJ$PHULFD5HDO(VWDWH*URXSDOVREDVHGLQWKH&KLFDJRDUHD -

Quick Facts 2004-05 Schedule Contents

Contents General Information Schedule/Quick Facts .........................1 Media Information ..............................2 Troutt-Wittmann Center ....................3 Southern Illinois University ...........4-5 SIU Arena .........................................6-9 Salukis in the NBA ......................10-11 Origin & History of the Saluki ...12-13 Chancellor Walter Wendler .............14 Paul Kowalczyk .................................15 Chris Lowery ...............................16-17 Assistant Coaches .......................18-19 2004-05 Preview Season Outlook ........................... 20-21 Rosters ............................................... 22 The Players Returning Veterans ....................24-35 Newcomers .................................36-42 2003-04 Recap 2004-05 Schedule Quick Facts Game Summaries ....................... 44-51 November The University Statistics ......................................52-54 Sun. 7 Missouri Southern (Exhibition) 5:05 p.m. Founded ..................................... 1869 Sun. 14 Lincoln University (Exhibition) 2:05 p.m. Enrollment ................................ 21,589 The Record Book Sun. 21 Augustana (lll.)• 2:05 p.m. Nickname ................................. Salukis Tues. 23 Tennessee State• 7:05 p.m. Colors .....................Maroon and White Year-By-Year Team Stats ........... 56-57 Fri. 26 Vanderbilt•• 5:00 p.m. (PST) Arena .................................. SIU Arena Chronological Lists .....................58-59 Sat. 27 TBA•• TBA Capacity ................................... -

The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan

ORDINANCE NO. 040826-56 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING THE AUSTIN TOMORROW COMPREHENSIVE PLAN BY ADOPTING THE CENTRAL AUSTIN COMBINED NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN. BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF AUSTIN: PARTI. Findings. (A) In 1979, the Cily Council adopted the "Austin Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan." (B) Article X, Section 5 of the City Charter authorizes the City Council to adopt by ordinance additional elements of a comprehensive plan that are necessary or desirable to establish and implement policies for growth, development, and beautification, including neighborhood, community, or area-wide plans. (C) In December 2002, the Central Austin neighborhood was selected to work with the City to complete a neighborhood plan. The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan followed a process first outlined by the Citizens' Planning Committee in 1995, and refined by the Ad Hoc Neighborhood Planning Committee in 1996. The City Council endorsed this approach for neighborhood planning in a 1997 resolution. This process mandated representation of all of the stakeholders in the neighborhood and required active public outreach. The City Council directed the Planning Commission to consider the plan in a 2002 resolution. During the planning process, the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team gathered information and solicited public input through the following means: (1.) neighborhood planning team meetings; (2) collection of existing data; (3) neighborhood inventory; (4) neighborhood survey; (5) neighborhood workshops; (6) community-wide meetings; and (7) a neighborhood final survey. Page 1 of 3 (D) The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan recommends action by the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team, City staff, and by other agencies to preserve and improve the neighborhood. -

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 JoinJoin UsUs inin T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A CONTENTS N 3 Why Come to Austin? PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS 37 AASLH Institutional A 6 About Austin 20 Wednesday, September 6 Partners and Patrons C I 9 Featured Speakers 39 Special Thanks SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS R 11 Top 12 Reasons to Visit Austin 40 Come Early and Stay Late 22 Thursday, September 7 E 12 Meeting Highlights and Sponsors 41 Hotel and Travel 28 Friday, September 8 M 14 Schedule at a Glance 43 Registration 34 Saturday, September 9 A 16 Tours 19 Special Events AUSTIN!AUSTIN! T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A N othing can replace the opportunitiesC ontents that arise A C when you intersect with people coming together I R around common goals and interests. E M A 2 AUSTIN 2017 oted by Forbes as #1 among America’s fastest growing cities in 2016, Austin is continually redefining itself. Home of the state capital, the heart of live music, and a center for technology and innovation, its iconic slogan, “Keep Austin Weird,” embraces the individualistic spirit of an incredible city in the hill country of Texas. In Austin you’ll experience the richness in diversity of people, histories, cultures, and communities, from earliest settlement thousands of years in the past to the present day — all instrumental in the growth of one of the most unique states in the country. -

Press = Herald

South ......... 46 West .... ... 62 Montgomery . 73 Torrance . '.". 82 Morningside . ITTTforth ........ 94 Redondo. ; .. 44 Aviation .. ... .54 Murphy ...... 35 Leuzinger ..... 70 Rolling Hills. 46 Hawthorne ... 56 Sweep to Victory A \ * HB » Kaw'-i *HH South North B reezes ^ ^ $t e#&?|tt8uj[ ^^H V Wins To 7th TFriumph By HENR V BURKE Pair Press-Herald Sports Editor In comparison with We Patent pending. dnesday's last second 4847 Wait for the final two sec win over Redondo, North 1High returned to its restyi- ffSPORTSB ished gym Friday night to " show up" Hawthorne, 94-56. ^^^^^HHBH^HHj^^l^^; ' ^^^iMlllL^L^L^L^LI onds and shoot from any where on the court. It will Coach Skip Enger's Saxons iupped their Bay League ree jeat Redondo every time. A-4 FEBRUARY 5, 1967 ord to 7-0 and set the stage fer Wednesday's showdown South used a 25-foot shot with second place Mira Costa. >y Chuck Fernandes to bea Micohi came away from a by seven with three minutes he Seahawks in their Bay 60-37 win over Inglewood Fri to go, Sims went outside the League game Friday night, day with a 6-1 record. key to direct a down-slow Tomas Leads West 46-44. North's Dan Hanson, who game. The Saxons went on It was the third straight scored only 4 points against defense and forced Redondo oss for defending champion Hawthorne, connected on a into a series of game decid ledondo. The team lost to 20-foot goal as the buzzer ing turnovers. tfira Costa in overtime las sounded to beat Redondo The margin was 3 point* To 62-54 Victory iYiday and dropped a 48-4' Wednesday.