Hyde Park: an Early Suburban Development in Austin, Texas (1891- 1941)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Central Texas Runners Guide: Information About Races and Running Clubs in Central Texas Running Clubs Running Clubs Are a Great Way to Stay Motivated to Run

APRIL-JUNE EDITION 2017 Central Texas Runners Guide: Information About Races and Running Clubs in Central Texas Running Clubs Running clubs are a great way to stay motivated to run. Maybe you desire the kind of accountability and camaraderie that can only be found in a group setting, or you are looking for guidance on taking your running to the next level. Maybe you are new to Austin or the running scene in general and just don’t know where to start. Whatever your running goals may be, joining a local running club will help you get there faster and you’re sure to meet some new friends along the way. Visit the club’s website for membership, meeting and event details. Please note: some links may be case sensitive. Austin Beer Run Club Leander Spartans Youth Club Tejas Trails austinbeerrun.club leanderspartans.net tejastrails.com Austin FIT New Braunfels Running Club Texas Iron/Multisport Training austinfit.com uruntexas.com texasiron.net New Braunfels: (830) 626-8786 (512) 731-4766 Austin Front Runners http://goo.gl/vdT3q1 No Excuses Running Texas Thunder Youth Club noexcusesrunning.com texasthundertrackclub.com Austin Runners Club Leander/Cedar Park: (512) 970-6793 austinrunners.org Rogue Running roguerunning.com Trailhead Running Brunch Running Austin: (512) 373-8704 trailheadrunning.com brunchrunning.com/austin Cedar Park: (512) 777-4467 (512) 585-5034 Core Running Company Round Rock Stars Track Club Tri Zones Training corerunningcompany.com Youth track and field program trizones.com San Marcos: (512) 353-2673 goo.gl/dzxRQR Tough Cookies -

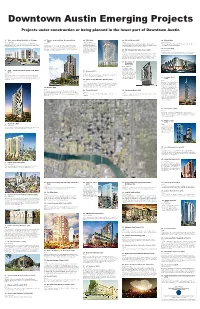

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects Projects under construction or being planned in the lower part of Downtown Austin 1. 7th & Lamar (North Block, Phase II) (C2g) 11. Thomas C. Green Water Treatment Plant 20. 7Rio (R60) 28. 5th and Brazos (C54) 39. Eleven (R86) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ (C56) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ Planned 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ &RQVWUXFWLRQLVXQGHUZD\DWWKHVLWHRIWKHIRUPHU.$6(.9(7UDGLR Planned &RQVWUXFWLRQVWDUWHGLQ0D\ $QH[LVWLQJYDOHWSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLOOEHWRUQGRZQDQGUHSODFHGE\DQ :RUNFRQWLQXHVRQWKLVXQLWPXOWLIDPLO\SURMHFWRQ(WK6WUHHW VWXGLREXLOGLQJIRUWKHFRQVWUXFWLRQRIDQHZSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWK 7KH*UHHQVLWHZLOOFRQVLVWRIVHYHUDOEXLOGLQJVXSWRVWRULHVWDOO RQWKLVXQLWDSDUWPHQW HLJKWVWRU\SDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWKVSDFHV7KDWJDUDJHVWUXFWXUHZLOODOVR RYHUORRNLQJ,DQGGRZQWRZQ$XVWLQ VIRIJURXQGÀRRUUHWDLO ,QFOXGLQJ%ORFN VHHEHORZ WKHSURMHFWZLOOKDYHPLOOLRQ WRZHUDW:WK6WUHHWDQG5LR LQFOXGHVTXDUHIHHWRIVWUHHWOHYHOUHWDLOVSDFH VTXDUHIHHWRIGHYHORSPHQWLQFOXGLQJDSDUWPHQWVVTIWRI *UDQGHE\&DOLIRUQLDEDVHG RI¿FHVSDFHDURRPKRWHODQGVTIWRIUHWDLO PRVWDORQJDQ GHYHORSPHQWFRPSDQ\&:6 40. Corazon (R66) H[WHQVLRQRIWKHQG6WUHHW'LVWULFW 7KHSURMHFWZDVGHVLJQHG 29. 5th & Brazos Mixed-Use Tower (C89) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ E\ORFDODUFKLWHFWXUDO¿UP Planned 5KRGH3DUWQHUV &\SUHVV5HDO(VWDWH$GYLVHUVLVEXLOGLQJ&RUD]RQDYHUWLFDOPL[HGXVH $VN\VFUDSHURIXSWRVWRULHVZLWKKRWHOURRPVDQGUHVLGHQFHVDW(DVW SURMHFWWKDWZLOOLQFOXGHUHVLGHQWLDOXQLWVUHWDLODQGDUHVWDXUDQW )LIWKDQG%UD]RVVWUHHWVGRZQWRZQ7KHWRZHUFRXOGLQFOXGHRQHRUWZR KRWHOVDQGPRUHWKDQKRXVLQJXQLWVPRVWOLNHO\DSDUWPHQWV&KLFDJR EDVHG0DJHOODQ'HYHORSPHQW*URXSZRXOGGHYHORSWKHSURMHFWZLWK :DQ[LDQJ$PHULFD5HDO(VWDWH*URXSDOVREDVHGLQWKH&KLFDJRDUHD -

2Nd Street District Austin, Texas 78701

FOR LEASE 2ND STREET DISTRICT AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 www.cbre.com/ucr FOR LEASE | 2ND STREET DISTRICT | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 PROPERTY INFO + The 2ND Street District is made up of the best shopping, dining and entertainment in Austin. + Heavy foot traffic during the week and on weekends. + Over 450 apartments immediately in the district, and within 1/4 mile from multiple condominiums and the two highest grossing hotels in the city, The JW Marriott and The W Hotel. + Tenants in the district include Austin City Limits Live at the Moody Theater, Violet Crown Cinema, Urban Outfitters, Jo’s Coffee, La Condesa, Milk & Honey, Lamberts, Austin Java, and many more. GROSS LEASABLE AREA + 144,137 SF AVAILABLE SPACE + 1,200 SF - 5,059 SF RATES | NNN + Please call for rates. www.cbre.com/ucr FOR LEASE | 2ND STREET DISTRICT | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 3RD STREE T BALLET AUSTIN BALLET Popbar AMLI on 2ND DEN Leasing Office At Lease AVAILABLE 1/1/18 Starbucks 5,059 S.F. Which Wich? Cathy’s Cleaners Peli Peli Royal Blue Grocery Daily Juice Finley’s Barber Shop Finley’s Barber Shop Con’ Olio G Con’ Olio U Austin Proper Sales Office A 2ND Street W Austin Away Spa D AMLI on 2ND District Office L A A AMLI DOWNTOWN W Austin Bar Chi V L A PUBLIC PARKING LACQUER U BLOCK 21 PUBLIC PARKING C BLOCK 22 P 110 PUBLIC PARKS | 34 STREET PARKS BLOCK 20 A E P 412 PUBLIC PARKS | 7 STREET PARKS $ 326 PUBLIC PARKS | 34 STREET PARKS Hacienda v P Trace AMLI Downtown Leasing Office PRIZE Authentic Smiles At Lease 3TEN Urban Outfitters Violet Crown Cinema LOFT Austin City Limits La Condesa & Malverde Crú Estilo ModCloth Taverna Taverna Circus Upstairs Upstairs Austin City Limits Live at the Moody Theatre Rocket Electrics Jo’s Hot Coffee Bonobos C Austin MacWorks Alimentari 28 Numero $ Design Within Reach O v L ORA Public Art 2ND STREE T D League ofEtcetera, Rebels etc. -

The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan

ORDINANCE NO. 040826-56 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING THE AUSTIN TOMORROW COMPREHENSIVE PLAN BY ADOPTING THE CENTRAL AUSTIN COMBINED NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN. BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF AUSTIN: PARTI. Findings. (A) In 1979, the Cily Council adopted the "Austin Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan." (B) Article X, Section 5 of the City Charter authorizes the City Council to adopt by ordinance additional elements of a comprehensive plan that are necessary or desirable to establish and implement policies for growth, development, and beautification, including neighborhood, community, or area-wide plans. (C) In December 2002, the Central Austin neighborhood was selected to work with the City to complete a neighborhood plan. The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan followed a process first outlined by the Citizens' Planning Committee in 1995, and refined by the Ad Hoc Neighborhood Planning Committee in 1996. The City Council endorsed this approach for neighborhood planning in a 1997 resolution. This process mandated representation of all of the stakeholders in the neighborhood and required active public outreach. The City Council directed the Planning Commission to consider the plan in a 2002 resolution. During the planning process, the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team gathered information and solicited public input through the following means: (1.) neighborhood planning team meetings; (2) collection of existing data; (3) neighborhood inventory; (4) neighborhood survey; (5) neighborhood workshops; (6) community-wide meetings; and (7) a neighborhood final survey. Page 1 of 3 (D) The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan recommends action by the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team, City staff, and by other agencies to preserve and improve the neighborhood. -

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 JoinJoin UsUs inin T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A CONTENTS N 3 Why Come to Austin? PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS 37 AASLH Institutional A 6 About Austin 20 Wednesday, September 6 Partners and Patrons C I 9 Featured Speakers 39 Special Thanks SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS R 11 Top 12 Reasons to Visit Austin 40 Come Early and Stay Late 22 Thursday, September 7 E 12 Meeting Highlights and Sponsors 41 Hotel and Travel 28 Friday, September 8 M 14 Schedule at a Glance 43 Registration 34 Saturday, September 9 A 16 Tours 19 Special Events AUSTIN!AUSTIN! T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A N othing can replace the opportunitiesC ontents that arise A C when you intersect with people coming together I R around common goals and interests. E M A 2 AUSTIN 2017 oted by Forbes as #1 among America’s fastest growing cities in 2016, Austin is continually redefining itself. Home of the state capital, the heart of live music, and a center for technology and innovation, its iconic slogan, “Keep Austin Weird,” embraces the individualistic spirit of an incredible city in the hill country of Texas. In Austin you’ll experience the richness in diversity of people, histories, cultures, and communities, from earliest settlement thousands of years in the past to the present day — all instrumental in the growth of one of the most unique states in the country. -

804 Congress Ave. | Austin, Texas 78701

804 CONGRESS AVE. | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 FOR MORE JASON STEINBERG, SIOR MATT LEVIN, SIOR INFORMATION 512.505.0004 512.505.0001 PLEASE CONTACT j [email protected] [email protected] 812 SAN ANTONIO | SUITE 105 | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 | 512.505.0000 | WWW.ECRTX.COM 804 CONGRESS NEW STREETSCAPE THE BOSCHE-HOGG BUILDING 804 CONGRESS AVENUE | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 FOR LEASE OFFICE | FOR MORE JASON STEINBERG, SIOR MATT LEVIN, SIOR INFORMATION 512.505.0004 512.505.0001 PLEASE CONTACT j [email protected] [email protected] 812 SAN ANTONIO | SUITE 105 | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 | 512.505.0000 | WWW.ECRTX.COM 804 CONGRESS PROPERTY INFORMATION THE BOSCHE-HOGG BUILDING 804 CONGRESS AVENUE | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 AVAILABILITY FOR LEASE Suite 300 - 6,770 RSF Available 7/1/17 OFFICE | PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 804 Congress, also known as The Bosche-Hogg Building, is a historic office building located in the heart of Downtown Austin. Only three blocks from the State of Texas Capitol building, it is in close proximity to both the Court House and the University of Texas. The building was built in 1897 and has had significant recent renovations, including a new Café Medici coffee bar within the updated lobby as well as a offering a rare outdoor park. It is within walking distance to dozens of restaurants and attractions, making it ideal for professional and creative users. Creative office suites, premier signage, several parking options, and State of Texas Capitol views makes this an attractive office lease opportunity. FEATURES BUILDING LOCATION SUITES • Six-story office -

Hospital Data Dictionary

HOSPITAL DATA DICTIONARY Texas Department of State Health Services EMS/Trauma Registry July 24, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Definitions ii 2002 Data File Formats iii Respiratory Rate for Trauma Score 12 Revised Trauma Score 13 Sex 2 Patient Demographics Software Identification 31 Main Fields Systolic Blood Pressure 8 (*Shaded fields are required or Systolic Blood Pressure at Scene 21 conditionally required. See page Systolic Blood Pressure for Trauma Score 12 TDH Firm Number (EMS ID#) 24 number referenced for clarification) Time of Arrival 7 (Body Region) Injury Severity 18 Time of Arrival to First Hospital 28 (Body Region) Type of Injury 18 Time of Departure from First Hospital 29 Abbreviated Injury Scale 17 Time of Discharge or Death 15 Alcohol Level 8 Time of Dispatch 24 Alcohol Level Tested 8 Time of Injury 4 Billed Hospital Charges 20 Time of Leaving The Scene 25 Cause of Injury 4 Time of Scene Arrival 25 City of Residence 30 Time of Trauma Team Activation 30 Condition on Discharge 14 Total Reimbursement 20 County of Injury 4 Transfer Status (Is This a Transfer?) 27 County of Residence 5 Trauma Registry Number 1 Date of Arrival 7 Trauma Team Activation 30 Date of Arrival to First Hospital 28 Vehicle Extrication 26 Date of Birth 3 Verbal Response 10 Date of Departure from First Hospital 29 Verbal Response at Scene 22 Date of Discharge or Death 15 Date of Injury 3 Diagnoses 17 32 Diastolic Blood Pressure 8 Research Fields Eye Opening Response 11 Desired Fields 33 Eye Opening Response at Scene 23 Appendices Facility Number 2 Appendix A -Hospitals – see ID Numbers web First Hospital Number 27 Appendix B - EMS Providers -see ID Numbers web Glasgow Coma Score at Admission 11 Appendix C - County Code List………………. -

AVAILABILITY REPORT Properties & Land for Lease Or Sale

RETAIL FOR SALE OFFICE FOR LEASE RETAIL FOR LEASE OFFICE FOR SALE SUBLEASE SPACE INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE INDUSTRIAL FOR SALE LAND FOR SALE AVAILABILITY REPORT Properties & Land for Lease or Sale April 2021 Austin, TX 5TH + TILLERY FEATURES AVAILABILITY PARKING RATE CONTACT 3:1,000 Matt Frizzell Class A building • 3 stories with abundant natural light • Decks Kevin Granger with panoramic views • 600 KW array of solar panels • Direct 182,716 RSF Surface $38.00 entry to suites • Automatic doors allowing for touchless entry to property APRIL 2021 | LISTING REPORT OFFICE SPACE for Lease PROPERTY AVAILABILITY RATE FEATURES CONTACT • Central location with easy access to TECH 3443 Highway 183 and entrances/exits on the 3443 Ed Bluestein Blvd. frontage road Austin, TX 78721 • Valet and reserved parking Melissa Totten Lease Call Broker • On-site building management Mark Greiner 327,278 RSF for Rate • State-of-the-art-fitness center with Property Flyer lockers and showers Charlie Hill • On-site healthcare services, yoga studio, bike path and bike storage NE • Direct access to Walnut Creek Bike Trail 5TH + TILLERY 618 Tillery St. Austin, TX 78702 • Class A building $40.00 NNN • 3:1,000 parking ratio Lease Matt Frizzell • 3 stories with tons of natural light ±182,716 RSF 2021 Est. OpEx Property Flyer $17.50 • Decks with panoramic views Kevin Granger • 600 KW array of solar panels Visit Website EAST UPLANDS CORP CENTER I & II UPLANDS I Lease 5301 Southwest Pkwy. • 4:1,000 SF parking; expandable to Austin, TX 78735 UPLANDS I 5.5/1,000 as needed 23,956 SF UPLANDS II Matt Frizzell Call Broker (Avail. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the WESTERN DISTRICT of TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION SHANNON PEREZ, Et Al., Plaintiffs, V

Case 5:11-cv-00360-OLG-JES-XR Document 1622 Filed 03/18/19 Page 1 of 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION SHANNON PEREZ, et al., Plaintiffs, CIVIL ACTION NO. v. SA-11-CA-360-OLG-JES-XR [Lead case] STATE OF TEXAS, et al., Defendants. DEFENDANTS’ REPLY TO MALC AND TLRTF’S RESPONSES REGARDING REMEDY FOR STATE HOUSE DISTRICT HD90 On February 23, 2019, the Court ordered Plaintiffs “to respond to Defendants’ advisory concerning the use of Plan H328 and notify the Court of any alternative proposals” by March 11, 2019. ECF No. 1619. On that date, TLRTF and MALC independently submitted their own proposed plans. ECF Nos. 1620, 1621. TLRTF resubmitted Plan H407, a proposed remedial plan that seeks to return HD90 to its configuration under Plan H283 and remove the Como neighborhood from HD90. But the Court has already considered and rejected Plan H407. ECF No. 1600. The Shaw violations found by the Court “rest on changes made to HD90 after Como was moved back into HD90.” Perez v. Abbott, 267 F. Supp. 3d 750, 794 (W.D. Tex. 2017); see also id. at 792 (finding racial considerations behind “changes made between Plan H328 and Plan H342”). Plan H407 is therefore inconsistent with the Court’s Case 5:11-cv-00360-OLG-JES-XR Document 1622 Filed 03/18/19 Page 2 of 8 instruction that any remedy in HD90 “must respect the legislative choices made in 2013, except to remedy the constitutional violations.” ECF No. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

Muffled Voices of the Past: History, Mental Health, and HIPAA

INTERSECT: PERSPECTIVES IN TEXAS PUBLIC HISTORY 27 Muffled Voices of the Past: History, Mental Health, and HIPAA by Todd Richardson As I set out to write this article, I wanted to explore mental health and the devastating toll that mental illness can take on families and communities. Born out of my own personal experiences with my family, I set out to find historical examples of other people who also struggled to find treatment for themselves or for their loved ones. I know that when a family member receives a diagnosis of a chronic mental illness, their life changes drastically. Mental illness affects individuals and their loved ones in a variety of ways and is a grueling experience for all parties involved. When a family member’s mind crumbles, often that person— the brother or father or favorite aunt— is gone forever. Families, left helpless, watch while a person they care for exists in a state of constant anguish. I understood that my experiences were neither new nor unique. As a student of history, I knew that other families’ stories must exist somewhere in the recorded past. By looking back through time, I hoped to shine a light on the history of American mental health policy and perhaps to make the voices of those affected by mental illness heard. Doing so might bring some sense of justice and awareness to the lives of people with mental illness in the present in the same way that history allows other marginalized groups to make their voices heard and reshape the way people perceive the past. -

Texas House Select Committee on Mental Health Interim Report

Interim Report to the 85th Texas Legislature House Select Committee on Mental Health December 2016 HOUSE SELECT COMMITTEE ON MENTAL HEALTH TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2016 A REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 85TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE FOUR PRICE CHAIRMAN COMMITTEE DIRECTOR SANDRA TALTON Select Committee On Mental Health DecemberJanuary 3,29, 2017 2016 Four Price P.O. Box 2910 Chairman Austin, Texas 78768-2910 The Honorable Joe Straus Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Members of the Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Select Committee on Mental Health of the Eighty-fourth Legislature hereby submits its interim report including recommendations for consideration by the Eighty-fifth Legislature. Respectfully submitted, _______________________ Four Price, Chair ___________________________ ______________________________ Joe Moody, Vice Chair Representative Greg Bonnen ___________________________ ______________________________ Representative Garnet Coleman Representative Sarah Davis ___________________________ ______________________________ Representative Rick Galindo Representative Sergio Munoz ___________________________ ______________________________ Representative Andy Murr Representative Toni Rose ___________________________ ______________________________ Representative Kenneth Sheets Representative Senfronia Thompson ___________________________ ______________________________ Representative Chris Turner Representative James White