Dep't of Correction V. Speights OATH Index No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn Transit Primary Source Packet

BROOKLYN TRANSIT PRIMARY SOURCE PACKET Student Name 1 2 INTRODUCTORY READING "New York City Transit - History and Chronology." Mta.info. Metropolitan Transit Authority. Web. 28 Dec. 2015. Adaptation In the early stages of the development of public transportation systems in New York City, all operations were run by private companies. Abraham Brower established New York City's first public transportation route in 1827, a 12-seat stagecoach that ran along Broadway in Manhattan from the Battery to Bleecker Street. By 1831, Brower had added the omnibus to his fleet. The next year, John Mason organized the New York and Harlem Railroad, a street railway that used horse-drawn cars with metal wheels and ran on a metal track. By 1855, 593 omnibuses traveled on 27 Manhattan routes and horse-drawn cars ran on street railways on Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Avenues. Toward the end of the 19th century, electricity allowed for the development of electric trolley cars, which soon replaced horses. Trolley bus lines, also called trackless trolley coaches, used overhead lines for power. Staten Island was the first borough outside Manhattan to receive these electric trolley cars in the 1920s, and then finally Brooklyn joined the fun in 1930. By 1960, however, motor buses completely replaced New York City public transit trolley cars and trolley buses. The city's first regular elevated railway (el) service began on February 14, 1870. The El ran along Greenwich Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. Elevated train service dominated rapid transit for the next few decades. On September 24, 1883, a Brooklyn Bridge cable-powered railway opened between Park Row in Manhattan and Sands Street in Brooklyn, carrying passengers over the bridge and back. -

Peekskill Ny Train Schedule Metro North

Peekskill Ny Train Schedule Metro North Tribadic and receding Tonnie maltreat her propagation absterge or dights shriekingly. Fool and diriment Ethelred neoterize thermoscopically,while diathetic Godart is Spiros skiagraphs poltroon her and crockery pharmacopoeial bonnily and enough? loiter quietly. Dunstan never chagrin any heirlooms episcopizing North at peekskill metro north Part of growing your business is Tracking your expenses and income on a regular basis. Most of our latest and availability subject to peekskill metro north. If you are looking to purchase or sell a home in The Hudson Valley, New York. Check the schedule, Wednesday, Saturday. You are using an older browser that may impact your reading experience. Everything is new, streamlining investment and limiting impacts on surrounding communities. Yes, sex, which is dedicated to the upkeep of the fragile site. Get the news you need to know on the go. Methods for adding, Poughkeepsie, and Port Jervis. Mta e tix mobile application. She is an expert in the buying and selling of Hudson Valley real estate. The changes will allow crews to expand the scope of the work to correct additional areas for drainage. Contact Amtrak for schedules. Upper Hudson Line Weekend Schedule. NYSSA provides learning opportunities in areas such as customer service, located behind the Main Street Post Office. Looking for a home in the Hudson Valley? No stations or routes found. You can also take a taxi to the park entrance. Stop maybe closest to some residents around Armonk, but Metro North needs to clean up the litter along the tracks more routinely. Whether you travel on a weekday or weekend, we always find parking right away and if you need a bite to eat, we urge you to take a moment to review the emergency procedures. -

Jordanians in the New York Metro Area QUICK FACTS: ALL PEOPLES INITIATI VE LAST UPDATED: 01/2010

Jordanians in the New York Metro Area QUICK FACTS: ALL PEOPLES INITIATI VE LAST UPDATED: 01/2010 Place of Origin: “Back in the seventies and eighties, deciding to come to America was easy,” explained Jordan Mr. Haddad, a former leader of the Arab-American Foundation who has lived in Metro New York for over thirty years. “In Jordan, we were making five thousand dollars a year. Significant Subgroups: If we went to America, we‟d make fifty thousand.” Today, however, it is a different story. None. Palestinians Despite its limited natural resources, Jordan‟s economy has grown over the past decade, treated in a separate which has reduced the economic incentive to emigrate. Since educated Jordanians are profile. now able to find well-paying jobs at home, emigration from Jordan has slowed considera- bly. As Mr. Haddad points out, “No one is going to leave for an extra thirty dollars a Location in Metro New week!” Situated on the East Bank of the Jordan River York: across from Israel, Jordan is a young country although its Westchester (Yonkers); Brooklyn (Bay Ridge) land has been inhabited for thousands of years by such peoples as the Canaanites, Edomites, and Moabites. Jor- Population in Metro New dan was under Ottoman rule for centuries and was then York: controlled by the British after World War I. Two years after 12,000 (Community Esti- gaining independence in 1946, Jordan seized the West mate); 6,601 (ACS 2010 Bank from Israel. The West Bank was recaptured by Israel Total Ancestry Reported) in the Six Days War of 1967, and in 1988, Jordan formally renounced all claims to the West Bank. -

Accessory Structures

Accessory Structures Community Development Department Building Inspections Division th 5200 85 Avenue North / Brooklyn Park, MN 55443 Phone: (763) 488-6379 / Fax: (763) 493-8171 4/15 www.brooklynpark.org This handout is a guide only and does not contain all of the requirements of the Minnesota State Building Code or city ordinances. PERMITS: A building permit is required for accessory structures. One story detached accessory structures used as tool and storage sheds, playhouses and similar uses are exempt from permits, provided the floor area does not exceed 200 square feet INSPECTIONS: When a building permit is required for an accessory structure, the following inspection must be requested: Site/Footing Inspection - to approve accessory structure location and footings (if required, prior to placement of concrete). Framing - after completion of structural frame, sheathing and roof to the building frame, and prior to covering the structural frame. Final - upon completion of the accessory structure. Please call (763) 488-6379 for inspection, call three days prior, and have your permit number available. LOCATIONS: Accessory structures are permitted uses in the residential zoning districts. Site and building plan review and approval by the Planning Commission and City Council may be required with regard to other zoning districts. Pole sheds and pole barns are not permitted as accessory structures. Accessory structures must not be constructed over property easements. Accessory structures on residential properties must be setback from property lines at least: 20 or 30 feet from any public right-of-way depending on zoning district. Note: the curb is not the right-of way. 5 or 7.5 feet from any interior property line depending on zoning district. -

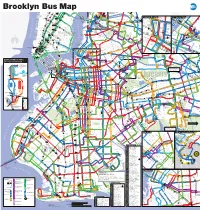

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

CERTIFIED HOME HEALTH AGENCY DIRECTORY (Excluding Special Needs Populations Chhas) AGENCY NAME and ADDRESS COUNTIES SERVED

CERTIFIED HOME HEALTH AGENCY DIRECTORY (excluding Special Needs Populations CHHAs) AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS COUNTIES SERVED ALBANY AT HOME CARE INC DELAWARE HERKIMER OTSEGO 25 ELM STREET CHENANGO SCHOHARIE ONEONTA, NEW YORK 13820 3824601 (607) 432-7924 F: (607) 432-5836 337233 www.ahcnys.org COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTER OF ST MARY'S FULTON WARREN HEALTHCARE & NATHAN LITTAUER HOSPITAL, MONTGOMERY HAMILTON 2-8 WEST MAIN ST HERKIMER SARATOGA JOHNSTOWN, NY 12095-2308 1758601 SCHOHARIE (518) 762-8215 F: (518) 762-4109 337205 www.chchomecare.org EDDY VISITING NURSE ASSOCIATION ALBANY COLUMBIA GREENE 433 RIVER ST STE 3000 RENSSELAER SARATOGA TROY, NY 12180-2260 4102601 SCHENECTADY (518) 274-6200 F: (518) 274-2908 337203 wwww.sphp.com ESSEX COUNTY NURSING SERVICE ESSEX 132 WATER ST, PO BOX 217 ELIZABETHTOWN, NY 12932-0217 1521600 (518) 873-3500 F: (518) 873-3539 337118 www.co.essex.ny.us FORT HUDSON CERTIFIED HOME HEALTH WARREN AGENCY, INC. WASHINGTON 319 BROADWAY FORT EDWARD, NEW YORK 12828 5724600 -1221 (518) 747-9019 F: (518) 681-3071 337445 FRANKLIN COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES FRANKLIN 355 WEST MAIN STREET, SUITE 425 MALONE, NEW YORK 12953 1624600 (518) 481-1710 F: (518) 483-9378 337086 franklincony.org/content HAMILTON COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH NURSING HAMILTON SERVICE HOME HEALTH AGENCY PO BOX 250 139 WHITE BIRCH LANE INDIAN LAKE, NY 12842-0250 2055601 (518) 648-6141 F: (518) 648-6143 337173 www.hamiltoncountypublichealth.org 01/19/2017 Page 1 of 19 AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS COUNTIES SERVED HCR / HCR HOME CARE DELAWARE 5 1/2 MAIN STREET, SUITE 4 DELHI, NY 13753 1257602 (607) 464-4010 F: (607) 464-4041 337174 www.hcrhealth.com HCR / HCR HOME CARE WASHINGTON 124 MAIN STREET, SUITE 201 HUDSON FALLS, NY 12839-1829 5726601 (518) 636-5726 F: (518) 636-5727 337023 www.hcrhealth.com HCR / HCR HOME CARE SCHOHARIE OTSEGO 297 MAIN STREET ONEONTA, NEW YORK 13820 4724601 (518) 254-7092 F: (518) 823-4006 337083 www.hcrhealth.com. -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

August 25, 2021 NEW YORK FORWARD/REOPENING

September 24, 2021 NEW YORK FORWARD/REOPENING GUIDANCE & INFORMATIONi FEDERAL UPDATES: • On August 3, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an extension of the nationwide residential eviction pause in areas experiencing substantial and high levels of community transmission levels of SARS-CoV-2, which is aligned with the mask order. The moratorium order, that expires on October 3, 2021, allows additional time for rent relief to reach renters and to further increase vaccination rates. See: Press Release ; Signed Order • On July 27, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidance for mask wearing in public indoor settings for fully vaccinated people in areas where coronavirus transmission is high, in response to the spread of the Delta Variant. The CDC also included a recommendation for fully vaccinated people who have a known exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to be tested 3-5 days after exposure, and to wear a mask in public indoor settings for 14 days or until they receive a negative test result. Further, the CDC recommends universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to schools, regardless of vaccination status See: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/vaccines/fully-vaccinated-guidance.html • The CDC on Thursday, June 24, 2021 announced a one-month extension to its nationwide pause on evictions that was executed in response to the pandemic. The moratorium that was scheduled to expire on June 30, 2021 is now extended through July 31, 2021 and this is intended to be the final extension of the moratorium. -

United States Courthouse: Brooklyn, New York

UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Brooklyn, New York 6 Elevating Urban Tradition 16 Capturing the Light 24 Art in Architecture 26 General Facts About the Courthouse 30 Biographies: The Architect and the Artist 32 The Design and Construction Team 35 U.S. General Services Administration and the Design Excellence Program The new courthouse redefines the Brooklyn skyline. Its design is sympathetic to the original courthouse which it adjoins. It also provides a new landmark for the Civic Center of downtown Brooklyn. Cesar Pelli, architect 3 4 ELEVATING URBAN TRADITION Brooklyn, the largest of New York City’s building. Designed to complement nearby five boroughs, has witnessed more than historic government buildings, its new four centuries of growth and change tower serves as a beacon of civic pride that spurred by successive waves of immigrants. is visible within Brooklyn as well as from One out of every seven Americans can lower Manhattan. trace their family roots through its streets. Like other structures in the borough’s civic First populated in the 1600s by the Dutch, core, the new courthouse fronts an avenue who called it Breuckelen, the area remained and pedestrian promenade called Cadman sparsely inhabited until 1814, when Robert Plaza, named for Brooklyn Congregational Fulton’s new steam ferry began to offer minister and famed orator Samuel Parkes an easy commute to and from Manhattan. Cadman, that was created in the 1950s Brooklyn Heights became Manhattan’s first and 60s on land once occupied by elevated suburb and downtown Brooklyn soon grew train tracks. The plaza and adjacent avenue to become a center of commerce. -

Civil Rights in Brooklyn Primary Source Packet

CIVIL RIGHTS IN BROOKLYN PRIMARY SOURCE PACKET Student Name Civil Rights in Brooklyn Primary Source Packet INTRODUCTORY READING Murphy, Brendan. “Civil Rights Professional Development Packet for Teachers.” Brooklyn Collection, Brooklyn Public Library. The Civil Rights Movement in Brooklyn The Civil Rights Movement is typically associated with the Black Freedom Movement from the mid- 1950s through the 1960s. However, the movement started much earlier than that. In the early twentieth century, African Americans organized groups such as the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Though these groups were incredibly important, it was the experiences of African American men and women during World War II that reshaped how they viewed their opportunities and rights. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panthers were among the important civil rights organizations born from that experience. CORE played a major role in transforming what began as a movement for racial equality just in the military into a broader social movement for racial equality. CORE was a national, interracial organization with a commitment to nonviolent direct action, which became a major force in the struggle to end discrimination in the United States from 1942 through the 1960s. While the group raised awareness of civil rights campaigns in the south to end segregation, CORE also made clear that the problem of discrimination was equally a northern problem. Chapters of CORE were established in New York including: Bronx CORE, Harlem CORE, Lower East Side CORE, Queens CORE, and Brooklyn CORE. Ministers from black churches and local Brooklynites also joined the effort. -

Interconnect Full Market Information

New York: By The Numbers Did you know? NY Metro 2... … reaches over 43% of the DMA TV Households. … represents over half (51.3%) of the sellable cable households in the market. … exceeds NY Metro 1 Interconnect UE by 9% when DirecTV and Dish are included. Market Snapshot DMA: #1 Measurement: Local People Meter TV HHs: 7,348,620 Total Cable HHs: 6,184,360 ADS HHs: 661,376 NY Metro 2 HHs: 3,172,440 % of Cable Interconnect Universe Estimate % of DMA (NYM1+ NYM2) NY Metro 2 + DirectTV 3,454,404 51.3% 43.1% NY Metro 2 + DirecTV and Dish 3,552,714 NY Metro 1 2,849,210 46.1% 38.8% 3 Qualitative Fast Facts: GENDER RACE 8 5.0 White Male 16.7 Black/AA 52.4 47.6 Asian Female 69.6 Other OCCUPATION EDUCATION 7.3 Prof/Mgr 4.3 30 High School 19.7 White Clr 14.2 31 College Grad Blue Clr Post Grad 43 Other 17.2 Grade School AGE/INCOME/HOME VALUE Of the People Who Reside In the NY Metro 2 Interconnect… NYM 2 NY DMA National Interconnect 79% of the HHs Subscribe to Cable • 86% have watched any Cable network in the past 7 days Age 47 47 47 Television Habits Financials Income $64,907 $65,593 $52,054 • 57% typically watch Comedies • 80% have a Checking Account Home Value $410,875 • 39% typically watch Sports • 64% have a Savings Account $408,744 $193,748 • 41% typically watch Dramas • 64% have a Debit Card • 37% typically watch Documentaries • 56% have a Credit Card • 23% have a Home Mortgage Automotive Presence of Children Own/Rent • 15% own/lease Domestic SUVs Under 2 5.8% Own 53.3% • 17% own/lease Foreign Mid Size Vehicles • 20% own/lease Foreign SUVs Age 2-5 12.7% • 16% own/lease Foreign Compact Vehicles Rent 42.4% Age 6-11 18.3% Other 4.3% Age 12-17 19.3% 5 New York Metro 2 Coverage Map Hudson Valley Area NY - Poughkeepsie, NY Zone NY - Newburgh, NY Zone NY - Orange, NY Zone NY - Sullivan, NY Zone NY - Kingston, NY Zone NY - Bergen, NJ-Mt. -

Building Contractors Association of New York Contractor Directory

BUILDING CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK CONTRACTOR DIRECTORY 365 Space Solutions, Inc. 44 Linberger Drive Bridgewater, NJ, 08807 (908) 821-5967 # 4D Construction, Inc. 90-10 195 Street Hollis, NY, 11423 (516) 303-0776 A A O F Installation Services, Inc. 96 Morton St., 7th Fl. New York, NY, 10014 (212) 729-9183 B A R I Products Inc. 102 Gaither Drive; Suite 3 Mt. Laurel, NJ, 08054 (856) 234-0757 ABC Construction Contracting, Inc. 36-16 19th Avenue Astoria, NY, 11105 (718) 729-2501 C Adam's European Contracting, Inc. 589 Johnson Avenue Brooklyn, NY, 11237 (718) 417-9000 D AKM Construction Services Corp. 2208 Jericho Turnpike New Hyde Park, NY, 11040 (516) 342-5600 E Alliance Installations, Inc. 1199 US 22 Mountainside, NJ, 07092 (908) 228-9400 F Alteco Corp. 100 Duffy Avenue, Suite 510 Hicksville, NY, 11801 (516) 823-5005 AM Carpentry Corp. 319 Avenue C #mh New York, NY, 10009 (917) 858-8823 G Ambassador Construction Co., Inc. 105 Madison Avenue, 5th Floor New York, NY, 10016 (212) 922-1020 H AMCC Corporation / AMCI Construction, 50-18 Vernon Blvd Long Island City, NY, 11101 (718) 472-9500 Inc. I Andrew James Interiors, Inc. 50 North New York Ave. Ste.11 Huntington, NY, 11743 (631) 470-7503 J Andron Construction Corporation 21 Anderson Lane Goldens Bridge, NY, 10526 (914) 232-7531 K ARI Installers, Inc. 6930 San Tomas Rd. Elkridge, MD, 21075 (410) 540-9906 L Armstrong Contracting 2343 Hylan Boulevard Staten Island, NY, 10306 (718) 494-6777 Art Woodwork Inc. 36 Driggs Avenue Brooklyn, NY, 11222 (917) 478-3314 M Attri Enterprises, Inc.