How to Become a Centaur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 12Th Top Chess Engine Championship

TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship Article Accepted Version Haworth, G. and Hernandez, N. (2019) TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship. ICGA Journal, 41 (1). pp. 24-30. ISSN 1389-6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190090 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76985/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190090 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online TCEC12: the 12th Top Chess Engine Championship Guy Haworth and Nelson Hernandez1 Reading, UK and Maryland, USA After the successes of TCEC Season 11 (Haworth and Hernandez, 2018a; TCEC, 2018), the Top Chess Engine Championship moved straight on to Season 12, starting April 18th 2018 with the same divisional structure if somewhat evolved. Five divisions, each of eight engines, played two or more ‘DRR’ double round robin phases each, with promotions and relegations following. Classic tempi gradually lengthened and the Premier division’s top two engines played a 100-game match to determine the Grand Champion. The strategy for the selection of mandated openings was finessed from division to division. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Evaluating Chess-Like Games Using Generated Natural Language Descriptions

Evaluating Chess-like Games Using Generated Natural Language Descriptions Jakub Kowalski?, Łukasz Żarczyński, and Andrzej Kisielewicz?? 1 Institute of Computer Science, University of Wrocław, [email protected] 2 Institute of Computer Science, University of Wrocław, [email protected] 3 Institute of Mathematics, University of Wrocław, [email protected] Abstract. We continue our study of the chess-like games defined as the class of Simplified Boardgames. We present an algorithm generating natural language descriptions of piece movements that can be used as a tool not only for explaining them to the human player, but also for the task of procedural game generation using an evolutionary approach. We test our algorithm on some existing human-made and procedurally generated chess-like games. 1 Introduction The task of Procedural Content Generation (PCG) [1] is to create digital content using algorithmic methods. In particular, the domain of games is the area, where PCG is used for creating various elements including names, maps, textures, music, enemies, or even missions. The most sophisticated and complex goal is to create the complete rules of a game [2–4]. Designing a game generation algorithm requires restricting the set of possible games to some well defined domain. This places the task into the area of General Game Playing, i.e. the art of designing programs which can play any game from some fixed class of games. The use of PCG in General Game Playing begins with the Pell’s Metagame system [5], describing the so-called Symmetric Chess-like Games. The evaluation of the quality of generated games was left entirely for the human expert. -

John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giff to US Chess

Included with this issue: 2021 Annual Buying Guide John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giftto US Chess DECEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com So you want to improve your chess? NEW! If you want to improve your chess the best place to start is looking how the great champs did it. dŚƌĞĞͲƟŵĞh͘^͘ŚĂŵƉŝŽŶĂŶĚǁĞůůͲ known chess educator Joel Benjamin ŝŶƚƌŽĚƵĐĞƐĂůůtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶƐĂŶĚ shows what is important about their play and what you can learn from them. ĞŶũĂŵŝŶƉƌĞƐĞŶƚƐƚŚĞŵŽƐƚŝŶƐƚƌƵĐƟǀĞ games of each champion. Magic names ƐƵĐŚĂƐĂƉĂďůĂŶĐĂ͕ůĞŬŚŝŶĞ͕dĂů͕<ĂƌƉŽǀ ĂŶĚ<ĂƐƉĂƌŽǀ͕ƚŚĞLJ͛ƌĞĂůůƚŚĞƌĞ͕ƵƉƚŽ ĐƵƌƌĞŶƚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶDĂŐŶƵƐĂƌůƐĞŶ͘ Of course the crystal-clear style of Bobby &ŝƐĐŚĞƌ͕ƚŚĞϭϭƚŚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶ͕ŵĂŬĞƐ for a very memorable chapter. ^ƚƵĚLJŝŶŐƚŚŝƐŬǁŝůůƉƌŽǀĞĂŶĞdžƚƌĞŵĞůLJ ƌĞǁĂƌĚŝŶŐĞdžƉĞƌŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂŵďŝƟŽƵƐ LJŽƵŶŐƐƚĞƌƐ͘ůŽƚŽĨƚƌĂŝŶĞƌƐĂŶĚĐŽĂĐŚĞƐ ǁŝůůĮŶĚŝƚǁŽƌƚŚǁŚŝůĞƚŽŝŶĐůƵĚĞƚŚĞŬ in their curriculum. paperback | 256 pages | $22.95 from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDS at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum – Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked CONTRIBUTORS DECEMBER Dan Lucas (Cover Story) Dan Lucas is the Senior Director of Strategic Communication for US Chess. He served as the Editor for Chess Life from 2006 through 2018, making him one of the longest serving editors in US Chess history. This is his first cover story forChess Life. { EDITORIAL } CHESS LIFE/CLO EDITOR John Hartmann ([email protected]) -

Portland Daily Press: September 06,1865

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. June S3,186S. Voi. 4. J-Mabusned WEDNESDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 1805. Term. $s PORTLAND, 0, p„ „,„mm ln mUance ---—_____32_; ~ DAILY PRESS: our hearts. It would, however,, be a melan- ——- --1 PORTLAND the little Miscellaneous. Miscellaneous. For Sale to choly satisfaction to us to find poor and Let. Wants, Lost and Found. Business Cards. JOHN T* GILMAN# Editor, mangled body, and consign it to a decent grave. Business Cards. At our becoming more accustomed PUBLISHED AT 82J EXCHANGE STREET, BY length eyes IMPORTANT SARR Streaked Mountain Place for Sale. to the state of we discovered that the Cow Lost. I>lt. If. A. ,s things, REASONS This is one of the best for sum- Notice. MALI., had covered the places a small red Cow with dark Copartnership N. A. FOSTER & CO. had fallen in, and floor mer The Sunday. Sept. 3d, ceiling boarding in the country. had a that in the where our ON htripes; leather tog attached to horns with its and place house is situated at the foot ol the morse 1 undersigned have funned a un- debris, '*G. B. Buzelie, Portland.’! Auy one re- copartnership physician and Daily Pbess is stood there was an enormous Mountain, and commands a view der the name and Arm of The Pobtland published at child’s bed had Why Persons Should Timber turningthe coW,or information of her,will be lilierallv THE surgeon, ■ Saw Mills lor natural loveliness cannot be #8.00 per year in advance. Limits, rewarded. GEO. B. pile of rubbish. surpassed——that BUZEiLE, U. T. -

2018 SCI National Conference

SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, INC. 2018 SCI National Conference JOEL PUCKETT, guest composer Featuring performances by Symphony Orchestra, Anna Wittstruck, conductor JAKE RUNESTAD, guest composer Wind Ensemble, Gerard Morris, conductor HEARTLAND MARIMBA QUARTET, guest ensemble Adelphian Concert Choir, Steven Zopfi, conductor ROB HUTCHINSON, host Dorian Singers, Kathryn Lehmann, conductor Clarinet Choir, Jennifer Nelson, conductor Flute Choir, Wendy Wilhelmi, conductor MARCH 1–3, 2018 Faculty performers: Catherine Case, Tim Christie, Tracy Knoop, University of Puget Sound Dawn Padula, Alistair MacRae, Maria Sampen, Tacoma, Washington and Tanya Stambuk PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUND SCHOOL OF MUSIC Additional funding provided by Matthew Norton Clapp Visiting Artist Endowment SCHOOL OF MUSIC presents 2018 SCI NATIONAL CONFERENCE March 1–3, 2018 University of Puget Sound Tacoma, Washington Rob Hutchinson, host Joel Puckett, guest composer Jake Runestad, guest composer featuring performances by Puget Sound Symphony Orchestra Puget Sound Wind Ensemble Adelphian Concert Choir Dorian Singers Puget Sound Clarinet Choir Puget Sound Flute Choir 2018 Society of Composers, Inc., National Conference, p. 2 Contents Welcome from Rob Hutchinson, Conference Host p. 3 Welcome from Keith Ward, Director, School of Music p. 4 Biographical summary of Joel Puckett, guest composer p. 5 Biographical summary of Jake Runestad, guest composer p. 6 Concert programs p. 7 Biographical information for composers and guest performers p. 28 Conference Schedule Thursday, March 1 6:30 – 7:30 p.m. Registration MUSIC BUILDING FOYER 7:30 p.m. Concert 1: Heartland Marimba Quartet SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL Friday, March 2 9–10 a.m. Registration and Coffee MUSIC BUILDING FOYER 10 a.m. Concert 2: Chamber Music 1 SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL Noon–2 p.m. -

WCSC 2013: the 3Rd World Chess Software Championship

WCSC 2013: the 3rd World Chess Software Championship Article Published Version Article Krabbenbos, J., Haworth, G. and van den Herik, J. (2013) WCSC 2013: the 3rd World Chess Software Championship. ICGA Journal, 36 (3). pp. 159-165. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/34052/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online The 3rd World Chess Software Championship (WCSC 2013) 159 THE 3RD WORLD CHESS SOFTWARE CHAMPIONSHIP (WCSC 2013) Jan Krabbenbos, Guy Haworth and Jaap van den Herik1 Amersfoort, Reading and Tilburg :&6&FRQWLQXHGWKH VHTXHQFHRI WRXUQDPHQWVGHVLJQHGWRSLWDXWKRUV¶FKHVVHQJLQHVDJDLQVWHDFK other on identical hardware platforms. It was held in parallel with WCCC 2013 from the 12th to the 18th of August and the same programs took part in a double round-robin format. The platform was an HP ELITEBOOK 8570W, with 16GB of RAM, 500GB HDD, and a 4-core Intel i7 3740QM Ivy Bridge processor supporting a potential 8 threads of activity7KHJDPHWHPSRZDVµDOOc + 15sPRYH¶ The 30 games (9 White wins, 10 draws and 11 Black wins) can be consulted on the web as played (ICGA, 2013) and also with evolving comments (Krabbenbos et al., 2013b) LQFOXGLQJ VRPH IURP µ08¶ 0DUN 8QLDFNH µ+:¶ +DUYH\ :LOOLDPVRQ µ-=¶ -RKDQQHV =ZDQ]JHU DQG IURP µ9$¶ :RUOG &KDPSLRQ 9LVK\ Anand (Williamson 2013). -

Lot No Description Res.–Est

Lot No Description Res.–Est. 500 Agriculture/Agriculture 15001 ENT U.S.A. (1864) Farmland. Postal stationery envelope (N) with corner advertisement for farm land near Philadelphia. "Good loam soil, highly productive for Wheat, Corn, Grass, Fruits and Vegetables." Prices are $25 to $35 an acre. Fascinating bit of agricultural history. .................. $30.00-- $25.00 15002 ENT U.S.A. (1874) Hoe. Interesting postal stationery envelope (N) with advertisement for some type of mechanical hoe, it reads:"The teeth of this machine drop in outward curves. It can be run much closer than any other, fairly hoeing any properly planted crop, and 10 acres a day, Then the ad just ends. Looks like only part of the entire ad was printed on the envelope. Perhaps there was supposed to be a picture also. Interesting!"" .................. $20.00-- $15.00 15003 ENT RUSSIA (1930) Farmer standing over fields. Illustrated postal propaganda card (O). Boosting Productivity! ..................................... $60.00-- $50.00 15004 ENT RUSSIA (1932) Tractors spraying fields. Insect pests. Illustrated postal propaganda card (O). ................................................. $60.00-- $50.00 15005 ENT RUSSIA (1932) Farming families at work. Illustrated postal propaganda card (O). Farmers, wives and children engaging in work. ................... $60.00-- $50.00 15006 ENT RUSSIA (1935) Man pointing at silo. Horse. Illustrated postal propaganda card (O). Take care of the collective farm! ............................. $60.00-- $50.00 15007 ENT U.S.A. (1935) Plow*. Seeder*. Sled*. Postal card with illustrated ad printed on back for agricultural implements. Scarce! ............................. $30.00-- $25.00 15008 EA FRANCE (1935) Workers in rice paddy*. Die proof in black signed by the engraver HERTENBERGER. -

The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants

THE CLASSIFIED ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CHESS VARIANTS I once read a story about the discovery of a strange tribe somewhere in the Amazon basin. An eminent anthropologist recalls that there was some evidence that a space ship from Mars had landed in the area a millenium or two earlier. ‘Good heavens,’ exclaims the narrator, are you suggesting that this tribe are the descendants of Martians?’ ‘Certainly not,’ snaps the learned man, ‘they are the original Earth-people — it is we who are the Martians.’ Reflect that chess is but an imperfect variant of a game that was itself a variant of a germinal game whose origins lie somewhere in the darkness of time. The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants D. B. Pritchard The second edition of The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants completed and edited by John Beasley Copyright © the estate of David Pritchard 2007 Published by John Beasley 7 St James Road Harpenden Herts AL5 4NX GB - England ISBN 978-0-9555168-0-1 Typeset by John Beasley Originally printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn Contents Introduction to the second edition 13 Author’s acknowledgements 16 Editor’s acknowledgements 17 Warning regarding proprietary games 18 Part 1 Games using an ordinary board and men 19 1 Two or more moves at a time 21 1.1 Two moves at a turn, intermediate check observed 21 1.2 Two moves at a turn, intermediate check ignored 24 1.3 Two moves against one 25 1.4 Three to ten moves at a turn 26 1.5 One more move each time 28 1.6 Every man can move 32 1.7 Other kinds of multiple movement 32 2 Games with concealed -

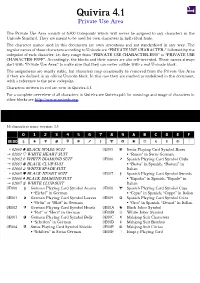

Quivira Private Use Area

Quivira 4.1 Private Use Area The Private Use Area consists of 6,400 Codepoints which will never be assigned to any characters in the Unicode Standard. They are meant to be used for own characters in individual fonts. The character names used in this documents are own inventions and not standardised in any way. The regular names of these characters according to Unicode are “PRIVATE USE CHARACTER-” followed by the codepoint of each character, i.e. they range from “PRIVATE USE CHARACTER-E000” to “PRIVATE USE CHARACTER-F8FF”. Accordingly, the blocks and their names are also self-invented. These names always start with “Private Use Area:” to make sure that they can never collide with a real Unicode block. The assignments are mostly stable, but characters may occasionally be removed from the Private Use Area if they are defined in an official Unicode block. In this case they are marked as undefined in this document, with a reference to the new codepoint. Characters written in red are new in Quivira 4.1. For a complete overview of all characters in Quivira see Quivira.pdf; for meanings and usage of characters in other blocks see http://www.unicode.org. Private Use Area: Playing Card Symbols 0E000 – 0E00F 16 characters since version 3.5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0E00 → 02660 ♠ BLACK SPADE SUIT 0E005 Swiss Playing Card Symbol Roses → 02661 ♡ WHITE HEART SUIT • “Rosen” in Swiss German → 02662 ♢ WHITE DIAMOND SUIT 0E006 Spanish Playing Card Symbol Clubs → 02663 ♣ BLACK CLUB SUIT • “Bastos” in Spanish, “Bastoni” in → 02664 -

WCSC 2019: the 9Th World Chess Software Championship

WCSC 2019: the 9th World Chess Software Championship Article Accepted Version The ICGA WCSC 2019 report Krabbenbos, J., van den Herik, J. and Haworth, G. (2020) WCSC 2019: the 9th World Chess Software Championship. ICGA Journal, 41 (4). pp. 222-236. ISSN 1389-6911 doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190126 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/85846/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: https://content.iospress.com/articles/icga-journal/icg190126 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ICG-190126 Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online WCSC 2019: The 9th World Chess Software Championship Jan Krabbenbos, Jaap van den Herik and Guy Haworth1 Amersfoort, the Netherlands, Leiden, the Netherlands and Reading, UK The 9th World Chess Software Championship started on August 11th, 2019. The six programs of Table 1 participated in a double round robin tournament of ten rounds. The tournament took place at the Venetian Macau Hotel Resort in Macau, China and was organized by the ICGA. The venue was part of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-19) which also acted as the main sponsor.