Autumn's Velocity Austin Robert Smith Freeport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Rubieże Kultury Popularnej

rubieże kultury popularnej Anna Nacher Rubieże kultury popularnej Popkultura w świecie przepływów recenzje anna nacher prof. dr hab. Eugeniusz Wilk prof. UAM dr hab. Marek Krajewski redakcja Karolina Sikorska ilustracje Paulina Płachecka projekt & opracowanie graficzne Magdalena Heliasz rubieże (txt publishing) copyright by Anna Nacher Galeria Miejska Arsenał druk Zakład Poligraficzny Moś i Łuczak, Poznań ISBN 978-83-61886-36-5 kultury wydawca Galeria Miejska Arsenał Stary Rynek 6 61-772 Poznań www.arsenal.art.pl dyrektor Wojciech Makowiecki partnerzy medialni kultura popularna popularnej popkultura w świecie przepływów Dofinansowano ze środków Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego Galeria Miejska Arsenał Poznań, 2012 – spis treści 10 212 Wstęp Rozdział szósty Rubieże kultury popularnej: Kontrkultury mediosfery między sceną a akademią – cyberaktywizm 28 242 Rozdział pierwszy Rozdział siódmy Taneczny culture jamming Kontrkultury substancji – pogranicza ciała – od halucynogenów do enteogenów 62 Rozdział drugi 282 PKP – polityczna kultura Rozdział ósmy popularna: od centrali do Kontrkultury czasu prowincji i z powrotem – kultura typu slow 92 306 Rozdział trzeci Rozdział dziewiąty Etnowyprzedaż? Miejskie ogrody Etnomuzykologia, world music albo miasto-ogród i Murzynek Bambo po partyzancku 146 338 Rozdział czwarty Rozdział dziesiąty Między eco-chic, Rewolucja ubrana w gadżety projektowaniem zaangażowanym albo wyblakły urok a ekokiczem hipsterstwa – ekologia jako styl życia 360 176 Bibliografia Rozdział piąty Kontrkultury mediosfery 388 – media taktyczne Appendix Rubieże kultury popularnej – między sceną a akademią 10 Rubieże kultury popularnej – między sceną a akademią 1111 wstęp Rubieże kultury popularnej – między sceną a akademią Kiedy otrzymałam propozycję poprowadzenia cyklu wy- kładów w poznańskiej Galerii Miejskiej Arsenał, poświęconych „rubieżom kultury popularnej”, porwała mnie fala entuzjazmu. Im bliżej było jednak pierwszego spotkania, tym wyraźniej mnożyły się wątpliwości. -

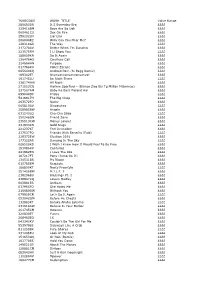

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Ireland Into the Mystic: the Poetic Spirit and Cultural Content of Irish Rock

IRELAND INTO THE MYSTIC: THE POETIC SPIRIT AND CULTURAL CONTENT OF IRISH ROCK MUSIC, 1970-2020 ELENA CANIDO MUIÑO Doctoral Thesis / 2020 Director: David Clark Mitchell PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES AVANZADOS: LENGUA, LITERATURA Y CULTURA Ireland into the Mystic: The Poetic Spirit and Cultural Content of Irish Rock Music, 1970-2020 by Elena Canido Muiño, 2020. INDEX Abstract .......................................................................................................................... viii Resumen .......................................................................................................................... ix Resumo ............................................................................................................................. x 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1.1. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1.2. Thesis Structure ............................................................................................................. 5 2. Historical and Theoretical Introduction to Irish Rock ........................................ 9 2.1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. The Origins of Rock ...................................................................................................... 9 2.1.3. -

Wishing on Dandelions a Novel

Wishing On Dandelions A novel By Mary E. DeMuth Mary E. DeMuth, Inc. P.O. Box 1503 Rockwall, TX 75087 Copyright 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission from Mary E. DeMuth, Inc, P.O. Box 1503, Rockwall, TX 75087, www.marydemuth.com. Cover design Mary DeMuth Cover photo by Mary E. DeMuth This novel is a work of fiction. Any people, places or events that may resemble reality are simply coincidental. The book is entirely from the imagination of the author. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations in this publication are taken from the King James Version (KJV). Other version used: the New American Standard Bible (NASB), copyright The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DeMuth, Mary E., 1967- Watching the Tree Limbs / Mary E. DeMuth p. cm. Includes biographical references. ISBN-10: 0983436754 ISBN-13: 978-0-9834367-5-1 1. Girls—fiction, 2. Rape victims—fiction 1. Title To those who wish for healing . Acknowledgements atrick, it blesses me that you read my novels, even when you don’t read novels, Pand tell me how they move your heart. I love you. I couldn’t have written this book without the insight of my critique group, Life Sentence. Leslie and D’Ann, thank you for plowing through the first draft with me and offering valuable words of encouragement and clarity. I love our Wednesday phone calls. I only wish I could import you to France! Thank you, prayer team, for faithfully praying -

Biography I'm a Multi-Award Winning Sound Designer / Mix Engineer With

Biography Employment I’m a multi-award winning sound designer / mix engineer with over Freelance - Sound Designer / Audio Post 10 years of industry experience working across an eclectic mix of 2008 - Present Advertising, Digital, Long Form, Promos, Branding and Film. I have won over 20 awards including D&AD, Music & Sound, New York — Advertising, Long Form Television, Promos, Film, Branding Festival, Cannes Lion, Kinsale, & British Arrow awards. Working with — Clients: Nike, Nokia, VW, Agent Provocateur, Secret Cinema, top agencies BBH, W+K, Mother, AMV, Adam&Eve, & Fallon. I have Armani Jeans. worked on brands such as Nike, Honda, Mercedes, VW, Armani & Virgin Media. I have also worked on long & short form television for Factory Studios - Sound Designer / Engineer broadcasters such as BBC, Channel 4, ITV, MTV, SKY, Virgin, Discovery 2011 - 2016 and freelanced at top studios such as Halo, Evolutions, Crow TV & BBC Post. I have a deep understanding of audio and a creative flair in — Advertising, Digital, VR, Films crafting sounds. I am highly motivated and work well within a team — Clients: BBH, Mother, Adam&Eve, W&K, WCRS, AMV. and independently. Good client hospitality and project time manage- — Brands: Honda, Nike, Mercedes, Stella, Google, Canon. ment even under pressure. On Demand Group - Sound Designer / Dubbing Mixer Skills 2009 - 2010 — Experienced and qualified 210P Pro Tools operator. — Promos — Creative flair in Sound Design. — Clients: Virgin Media, Film Flex, Various foreign clients — Highly experienced in VO / ADR recording and client hospitality. — Fluent in all AVID control surfaces, SSL desks. Ascent Media - Dubbing Mixer / Sound Designer — Technical Knowledge: DOLBY ATMOS / 7.1/ 5.1, DOLBY E, 2008 - 2009 ISDN, Source Connect, Binaural, VR, Nugen, Sound Recording — Third Party Plugin’s: Waves, iZotope, Sound Toys, Sonomic, — Promos Sound Miner, Audio Ease, Native Instruments. -

Copy of CDLIST

CD LIST FOR RICK OBEY'S ENTERTAINMENT SONG ARTIST ALBUM 3:00 AM MATCHBOX 20 PROMO ONLY RADIO 11/97 7 PRINCE THE HITS 1 19 PAUL HARDCASTLE ROCK OF THE 80'S 24 JEM PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT MARCH 2005 360 JOSH HOGE PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT JULY 2006 409 THE BEACH BOYS GREATEST HITS 1963 NEW ORDER SUBSTANCE DISC 2 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS PROMO ONLY CLUB 4/96 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT JULY 2004 1999 PRINCE DJ TOOLS VOLUME 7 1999 PRINCE THE HITS 1 1999 PRINCE PROMO ONLY-CLUB-DEC. '98 TITO PUENTE JR & THE LATIN ( ACCAPELLA) RHYTHM ETHNIC-OYE COMO VA MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON SWINGIN SINGLES #1 NELLY COLD PROMO ONLY-RADIO-OCT. 2001 $250 A HEAD ALAN SILVESTRI SOUND TRACK- FATHER OF THE BRIDE LUTHER VANDROSS & MARIAH ( INSTRUMENTAL) CAREY ENDLESS LOVE (BABY) HULLY GULLY THE OLYMPICS ULTIMATE 50'S PARTY (GOD MUST HAVE SPENT) A LITTLE MORE TIME ON YOU N SYNC PROMO ONLY-RADIO-NOV. 98 (HOT S**T) COUNTRY GRAMMAR NELLY PROMO ONLY-RADIO-AUG. '00 (HOW COULD YOU) BRING HIM HOME EAMON PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT AUGUST 2006 (I HATE) EVERYTHING ABOUT YOU THREE DAYS GRACE PROMO ONLY RADIO JANUARY 2004 (I JUST) DIED IN YOUR ARMS CUTTING CREW SOUNDS OF THE 80'S (1987) (I KNOW) I'M LOSING YOU UPTOWN GIRLS LOSING YOU (I) GET LOST ERIC CLAPTON PROMO ONLY - CLUB-DEC. '99 (MUCHO MAMBO)SWAY SHAFT PROMO ONLY-CLUB-NOV. '99 (MUNCHO MAMBO) SWAY (RADIO EDIT) SHAFT BURN THE FLOOR (NOT THE)GREATEST RAPPER 1000 CLOWNS PROMO ONLY-RADIO-FEB. -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

Loverboy the GOSPELTRUTH

ft I March 27, 1982 I I Loverboy THE GOSPELTRUTH ASCAP member won 16 Dove Awards in 1981. More than all the other licensing oiganizations combined. DOTTIE RAMBO Gospel Songwriter of the Year DOTTIE RAMBO Writer of Gospel Song of the Year “WE SHALL BEHOLD HIM” JOHN T. BENSON Publisher of Gospel Song of the Year “WE SHALL BEHOLD HIM” PUBLISHING CO. RUSS TAEE Male Vocalist of the Year DINO KARTSONAKIS Gospel InstrumenLilist of the Year PAUL SMITH Of the Imperials — Gospel Group of the Year PAUL SMITH Of the Imperials — Contemporaiv' Gospel Album of the Year “PRIORITY” MICHAEL OMARTIAN Producer of Contemporary' Gospel Album of the Year “PRIORITY” KLJRT KAISER Producer of Inspirational Gospel Album of the Year “JONES SONG” BOB MacKENZIE Producer Gospel Album of the Year — Children’s Music “KIDS UNDER CONSTRUCTION” RON HUEF Producer Gospel Album of the Year— Children’s Music “KIDS UNDER CONSTRUCTION” RON HUEE Producer of Gospel Album of the Year — Worship Music “EXALTATION” DON WYRTZEN Producer of Gospel Album of the Year — Musicals “THE LOVE STORY’ EDWIN HAWKINS Artist — Inspirational Gospel Album of the Year ( Black ) “EDWIN HAWKINS LIVE” EDWIN HAWKINS Producer— Inspirational Gospel Album of the Year ( Black) “EDWIN ILAVKINS LIVE” KEN HARDING Producer of Traditional Gospel Album of the Year “ONE STEP CLOSER” QSCQbAmerican Society of Composers, Authors & Publishers We've always had the greats. VOLUME XLIII -- NUMBER 44 — March 27, 1982 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY C4SH BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NICK ALBARANO Vice President EDITORML Throw The Book At ’Em ALAN SUTTON Vice President and Editor In Chief The news last week that the Motion Picture Assn, Unfortunately, with the current state of J.B. -

Approved Judgment

Neutral Citation Number: [2016] EWCA Civ 1214 Case No: A3/2014/1401 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM CHANCERY DIVISION Mr Justice Birss HC12A02971 Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 01/12/2016 Before : LORD JUSTICE BRIGGS LORD JUSTICE FLOYD and LORD JUSTICE CHRISTOPHER CLARKE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : WADE & ANR Appellants - and - BRITISH SKY BROADCASTING LIMITED Respondents - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ms Christina Michalos (instructed by Payne Hicks Beach ) for the Appellants Mr John Baldwin QC and Ms Lindsay Lane (instructed by Charles Russell Speechlys ) for the Respondents Hearing date : 22 November 2016 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Wade & Anr v British Sky Broadcasting Limited Lord Justice Briggs: 1. This appeal arises out of an unsuccessful claim for mis-use of confidential information. The claim was brought by the co-creators and promoters of a proposed television talent show who believe that the gist of their innovative format was copied by the defendant British Sky Broadcasting Limited (“Sky”) in order to produce a television programme which, although differently named, was suspiciously similar to their own. They allege that the appearance of a combination of original features in both formats, coupled with the short time between their pitch of their format to Sky, and the later televising of its talent show, raises the irresistible inference that, consciously or unconsciously, the key features of their format were misused by being copied, without their consent, by Sky. 2. By contrast with the law relating to private confidences, which has been transformed by the influence of the Human Rights Convention, the law relating to mis-use of confidential information in a business context has been well settled for very many years. -

Volume 40, Number 06 (June 1922) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1922 Volume 40, Number 06 (June 1922) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 40, Number 06 (June 1922)." , (1922). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/691 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Price 25 Cents Theo. Presser Co., Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa. $2.00 a Year Many Progressive Teachers Are Planning Summer Study Classes Summer for the coming vacation period A prime requisite for successfully conducting a 1 idgS ENTERTAINING AND INSTRUCTIVE MUSICAL LITERATURE special study class is the selection of an interest¬ Acquire a More Complete Musical Knowledge ing and brief, yet comprehensive text book. Through- Reading Such Books as These St/Gcisr/OJVS FOR MUSIC LOVERS OF ALL AGES These Meritorious Works Anecdotes of Great Great Singers on the Musicians contain excellent material for this purpose; the Art of Singing subject matter is given in a clear, simple and By James Francis Cooke hudred well authenticated ancedotes of composers, players and singers told direct style enabling the instructor to cover the entertaining style and embodying much brook,rlcl^pteiC°giving advice and science* ground thoroughly in a limited amount of time.