Intramuscular Injections: GUIDELINES for BEST PRACTICE B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Intramuscular Injection Is an Injection Given Directly Into The

Depo Lupron and Testosterone are both given by intramuscular injection. The following is a guideline on their administration. Eileen Durham, RN, NP Version 12 Jan 2010 Description Intramuscular (IM) injections are given directly into the central area of selected muscles. There are a number of sites that are suitable for IM injections; there are three sites that are most commonly used in this procedure described below. The volume of viscosity of the medication to be injected determines the site that should be used. IM injections cause stretching of the muscle fiber so the larger the muscle used the less discomfort. Intramuscular Injection Sites Depo Lupron Depo Lupron 3 month preparation should only be injected into the Gluteus medius due to the viscosity and volume of the medication approx. 1.5 – 2 cc. Depo Lupron 1 month preparation can be injection into the vastus lateralis or the gluteus medius. Testosterone Testosterone administered to adolescents and adults can be injected into any of the sites listed below, as long as the volume is 1 cc or less. For a volume of 1.5 use the vastus lateralis or Gluteus medius, if the volume is 2 cc you must you the largest muscle the Gluteus medius. If the volume is greater then 2 cc you must divide the dose and give 2 injections as the maximum volume in the Gluteal muscle is 2 cc. Testosterone administered to infants and toddlers use only the anteriolateral aspect of the thigh. Deltoid muscle The deltoid muscle located laterally on the upper arm can be used for intramuscular injections. -

Intravenous Therapy Procedure Manual

INTRAVENOUS THERAPY PROCEDURE MANUAL - 1 - LETTER OF ACCEPTANCE __________________________________________ hereby approves (Facility) the attached Reference Manual as of _____________________. (Date) The Intravenous Therapy Procedure Manual will be reviewed at least annually or more often when deemed appropriate. Revisions will be reviewed as they occur. Current copies of the Intravenous Therapy Procedure Manual shall be maintained at each appropriate nursing station. I have reviewed this manual and agree to its approval. __________________________ (Administrator) __________________________ (Director of Nursing) __________________________ (Medical Director) - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A. Purpose 1 B. Local Standard of Practice 1 RESPONSIBILITIES A. Responsibilities: M Chest Pharmacy 1 B. Responsibilities: Administrator 1 C. Responsibilities: Director of Nursing Services (DON/DNS) 1 D. Skills Validation 2 AMENDMENTS GUIDELINES A. Resident Candidacy for IV Therapy 1 B. Excluded IV Medications and Therapies 1 C. Processing the IV Order 1 D. IV Solutions/Medications: Storage 2 E. IV Solutions/Medications: Handling 3 F. IV Solutions and Supplies: Destroying and Returning 4 G. IV Tubing 5 H. Peripheral IV Catheters and Needles 6 I. Central Venous Devices 7 J. Documentation and Monitoring 8 K. IV Medication Administration Times 9 L. Emergency IV Supplies 10 I TABLE OF CONTENTS PROTOCOLS A. IV Antibiotic 1 1. Purpose 2. Guidelines 3. Nursing Responsibilities B. IV Push 2 1. Purpose 2. Guidelines C. Anaphylaxis Allergic Reaction 4 1. Purpose 2. Guidelines 3. Nursing Responsibilities and Interventions 4. Signs and Symptoms of Anaphylaxis 5. Drugs Used to Treat Anaphylaxis 6. Physician Protocol PRACTICE GUIDELINES A. Purpose 1 B. Personnel 1 C. Competencies 1 D. -

Injection Technique 1: Administering Drugs Via the Intramuscular Route

Copyright EMAP Publishing 2018 This article is not for distribution except for journal club use Clinical Practice Keywords Intramuscular injection/ Medicine administration/Absorption Practical procedures This article has been Injection technique double-blind peer reviewed Injection technique 1: administering drugs via the intramuscular route rugs administered by the intra- concerns that nurses are still performing Author Eileen Shepherd is clinical editor muscular (IM) route are depos- outdated and ritualistic practice relating to at Nursing Times. ited into vascular muscle site selection, aspirating back on the syringe Dtissue, which allows for rapid (Greenway, 2014) and skin cleansing. Abstract The intramuscular route allows absorption into the circulation (Dough- for rapid absorption of drugs into the erty and Lister, 2015; Ogston-Tuck, 2014). Site selection circulation. Using the correct injection Complications of poorly performed IM Four muscle sites are recommended for IM technique and selecting the correct site injection include: administration: will minimise the risk of complications. l Pain – strategies to reduce this are l Vastus lateris; outlined in Box 1; l Rectus femoris Citation Shepherd E (2018) Injection l Bleeding; l Deltoid; technique 1: administering drugs via l Abscess formation; l Ventrogluteal (Fig 1, Table 1). the intramuscular route. Nursing Times l Cellulitis; Traditionally the dorsogluteal (DG) [online]; 114: 8, 23-25. l Muscle fibrosis; muscle was used for IM injections but this l Injuries to nerves and blood vessels muscle is in close proximity to a major (Small, 2004); blood vessel and nerves, with sciatic nerve l Inadvertent intravenous (IV) access. injury a recognised complication (Small, These complications can be avoided if 2004). -

22428 Moxifloxacin Statisical PREA

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Translational Science Office of Biostatistics S TATISTICAL R EVIEW AND E VALUATION CLINICAL STUDIES NDA/Serial Number: 22,428 Drug Name: Moxifloxacin AF (moxifloxacin hydrochloride ophthalmic solution) 0.5% Indication(s): Treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis Applicant: Alcon Pharmaceuticals, Ltd. Date(s): Letter date:21 May 2010; Filing date: 18 June, 2010; PDUFA goal date: 19 November 2010 Review Priority: Priority Biometrics Division: Anti-infective and Ophthalmology Products Statistical Reviewer: Mark. A. Gamalo, Ph.D. Concurring Reviewers: Yan Wang, Ph.D. Medical Division: Anti-infective and Ophthalmology Products Clinical Reviewer: Lucious Lim, M.D. Project Manager: Lori Gorski Keywords: superiority, Moxifloxacin hydrochloride ophthalmic solution, bacterial conjunctivitis, bulbar conjunctival injection, conjunctival discharge/exudate TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF TABLES.......................................................................................................................... 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 4 1. 1 Conclusions and Recommendations..................................................................................... 4 1. 2 Brief Overview of Clinical Studies ..................................................................................... -

Self-Administering a Vitamin B12 Injection

Self-administering a Vitamin B12 injection This is usually given as an intramuscular injection, every 2-3 months. Alternatives to an intramuscular injection are: Oral Vitamin B12 at a dose of at least 1000mcg per day. • Available as tablets or a spray. They can be bought over the counter and available at most health food stores and pharmacies. • Oral Vitamin B12 is not recommended if: - If you have a bowel condition such as inflammatory bowel disease, Coeliac disease, small bowel overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption and short bowel (you will require injections) - You require an initial loading of B12 (soon after diagnosis) It is important to monitor your symptoms if you change to oral B12. If symptoms return, then the oral/sublingual dose can be increased to 2000mcg or you may need to consider starting back on injections. https://www.hollandandbarrett.com/shop/product/betteryou-pure-energy-b12-boost-oral-spray-60099160?skuid=099160 https://www.hollandandbarrett.com/search?query=%20Vitamin%20B12%20Tablets&utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=google&isSearch=true# gclid=EAIaIQobChMIh5nLgOH26AIVxLTtCh0JIA_GEAAYASAAEgJL-fD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds Subcutaneous (SC) injection; this is off-licence but still effective. It is considered an easier method of administration. It is how insulin and blood thinning medication are usually self-administered. Equipment needed to self-inject - Prescribed medicine - 1 syringe (2 ml) - 2 needles (1 for drawing up the drug and 1 for administration – you can use the same size needle for both). o For an IM injection; the needle gauge should be 19-25. The needle length is 1- 1 ½ inches (up to 3 inches for larger adults) o For a SC injection; the needle gauge should be 25-27. -

Informed Consent for Medication, Zyprexa

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH SERVICES STATE OF WISCONSIN Division of Care and Treatment Services 42 CFR483.420(a)(2) F-24277 (09/2016) DHS 134.31(3)(o) DHS 94.03 & 94.09 §§ 51.61(1)(g) & (h) INFORMED CONSENT FOR MEDICATION Dosage and / or Side Effect information last revised on 04/16/2021 Completion of this form is voluntary. If not completed, the medication cannot be administered without a court order unless in an emergency. This consent is maintained in the client’s record and is accessible to authorized users. Name – Patient / Client (Last, First MI) ID Number Living Unit Date of Birth , Name – Individual Preparing This Form Name – Staff Contact Name / Telephone Number – Institution ANTICIPATED RECOMMENDED MEDICATION CATEGORY MEDICATION DOSAGE DAILY TOTAL DOSAGE RANGE RANGE Antipsychotic / Bipolar Agent Zyprexa oral tablet; Oral: 2.5 mg-50 mg with most doses in Zyprexa Zydis oral the 2.5 mg-20 mg range disintegrating tablet; IM: 5 mg-10 mg per dose, up to 3 doses Zyprexa Intramuscular 24 hours Injection; Long Acting Injectable: 150 mg-300 mg Zyprexa Relprevv IM every 2 weeks, Intramuscluar Injection 300 mg-405 mg IM every 4 weeks (olanzapine) The anticipated dosage range is to be individualized, may be above or below the recommended range but no medication will be administered without your informed and written consent. Recommended daily total dosage range of manufacturer, as stated in Physician’s Desk Reference (PDR) or another standard reference. This medication will be administered Orally Injection Other – Specify: 1. Reason for Use of Psychotropic Medication and Benefits Expected (note if this is ‘Off-Label’ Use) Include DSM-5 diagnosis or the diagnostic “working hypothesis.” 2. -

Product Monograph

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr SANDOZ ONDANSETRON ODT Ondansetron Orally Disintegrating Tablets 4 mg and 8 mg ondansetron Manufacturer Standard Pr SANDOZ ONDANSETRON Ondansetron Tablets 4 mg and 8 mg ondansetron (as ondansetron hydrochloride dihydrate) Manufacturer Standard PrONDANSETRON INJECTION USP (ondansetron hydrochloride dihydrate) 2 mg/mL PrONDANSETRON HYDROCHLORIDE DIHYDRATE INJECTION Ondansetron Injection Manufacturer Standard 2 mg/mL Ondansetron (as ondansetron hydrochloride dihydrate) for injection Antiemetic (5-HT3-receptor antagonist) Sandoz Canada Inc. Date of Preparation: 145 Jules-Léger September 26, 2016 Boucherville, Québec, Canada J4B 7K8 Control No.: 198381 Ondansetron by Sandoz Page 1 of 43 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .......................................................... 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ................................................................................. 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ....................................................................................... 4 CONTRAINDICATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS .......................................................................................... 5 ADVERSE REACTIONS ............................................................................................................ 7 DRUG INTERACTIONS ............................................................................................................ -

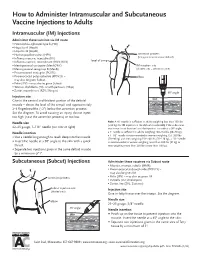

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccines to Adults

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccine Injections to Adults Intramuscular (IM) Injections Administer these vaccines via IM route • Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) • Hepatitis A (HepA) • Hepatitis B (HepB) • Human papillomavirus (HPV) acromion process (bony prominence above deltoid) • Influenza vaccine, injectable (IIV) • level of armpit • Influenza vaccine, recombinant (RIV3; RIV4) • Meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) IM injection site • Meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) (shaded area = deltoid muscle) • Pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) • Pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV23) – elbow may also be given Subcut • Polio (IPV) – may also be given Subcut • Tetanus, diphtheria (Td), or with pertussis (Tdap) • Zoster, recombinant (RZV; Shingrix) 90° angle Injection site skin Give in the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle – above the level of the armpit and approximately subcutaneous tissue 2–3 fingerbreadths (~2") below the acromion process. See the diagram. To avoid causing an injury, do not inject muscle too high (near the acromion process) or too low. Needle size Note: A ⅝" needle is sufficient in adults weighing less than 130 lbs (<60 kg) for IM injection in the deltoid muscle only if the subcutane- 22–25 gauge, 1–1½" needle (see note at right) ous tissue is not bunched and the injection is made at a 90° angle; Needle insertion a 1" needle is sufficient in adults weighing 130–152 lbs (60–70 kg); a 1–1½" needle is recommended in women weighing 153–200 lbs • Use a needle long enough to reach deep into the muscle. (70–90 kg) and men weighing 153–260 lbs (70–118 kg); a 1½" needle • Insert the needle at a 90° angle to the skin with a quick is recommended in women weighing more than 200 lbs (91 kg) or thrust. -

Efficacy/Risk Profile of Triamcinolone Acetonide in Severe Asthma

ARTICLE IN PRESS Respiratory Medicine CME (2008) 1, 111–115 respiratory MEDICINE CME CASE REPORT Efficacy/risk profile of triamcinolone acetonide in severe asthma: Lessons from one case study Cesar Picadoà Servei de Pneumologia, Hospital Clinic, Universitat de Barcelona, Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain Received 26 November 2007; accepted 22 January 2008 KEYWORDS Summary Insulin; Some prednisone-resistant asthma patients respond to intramuscular triamcinolone Refractory asthma; acetonide (TA). The use of TA has been questioned on the basis of its potential toxicity. Severe asthma; TA’s ratio of clinical efficacy to systemic effects compared with oral prednisone has not Steroid-dependent been clearly defined. asthma; We report the case of a prednisone-insensitive severe asthma patient with insulin- Triamcinolone dependent diabetes, hypertension and diabetic retinopathy treated with repeated sessions acetonide of laser therapy. By daily monitoring the needs of insulin doses we compared the systemic effects of prednisone and TA. The analysis of the balance between systemic effects (insulin doses) and beneficial effects (PEF values) show that TA has a better benefit/risk profile than prednisone. The patient has been followed up for 3 years and has received injections of TA repeated at intervals ranging from 21 to 60 days according to patient response and the evolution of PEF and clinical symptoms. During this period the patient lost 3 kg of weight, while presenting increased bone mineral density, normalized arterial tension, and improved proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The present case report shows that TA has a better benefit/risk profile than prednisone. TA can be a valuable alternative in the control of some patients with severe prednisone- resistant asthma. -

How to Administer Intramuscular, Intradermal, and Intranasal Influenza Vaccines

How to Administer Intramuscular, Intradermal, and Intranasal Influenza Vaccines Intramuscular injection (IM) Intradermal administration (ID) Intranasal administration (NAS) Inactivated Influenza Vaccines (IIV), including Inactivated Influenza Vaccine (IIV) Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (LAIV) recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3) 1 Gently shake the microinjection system before 1 FluMist (LAIV) is for intranasal administration 1 Use a needle long enough to reach deep into administering the vaccine. only. Do not inject FluMist. the muscle. Infants age 6 through 11 mos: 1"; 1 through 2 yrs: 1–1¼"; children and adults 2 Hold the system by placing the 2 Remove rubber tip protector. Do not remove 3 yrs and older: 1–1½". thumb and middle finger on dose-divider clip at the other end of the sprayer. the finger pads; the index finger 2 With your left hand*, bunch up the muscle. should remain free. 3 With the patient in an upright position, place the tip just inside the nostril 3 With your right hand*, insert the needle at a 3 Insert the needle perpendicular to the skin, to ensure LAIV is delivered into 90° angle to the skin with a quick thrust. in the region of the deltoid, in a short, quick the nose. The patient should movement. breathe normally. 4 Push down on the plunger and inject the entire contents of the syringe. There is no need to 4 Once the needle has been 4 With a single motion, depress plunger as aspirate. inserted, maintain light pressure rapidly as possible until the dose-divider clip on the surface of the skin and prevents you from going further. -

Self-Administering an Intramuscular Injection

Self-administering an Intramuscular injection If you have testosterone injections: - You can consider self-injecting Sustanon. - We do not recommend self-administration of Nebido as this is a more difficult to give (due to the high viscosity and preferred site of administration). If you wish to switch from Nebido to Sustanon, so you can self-inject, we will get advice from your GIC - A change to testosterone gel is an option. If this is something you wish to consider then please discuss with your GIC or a medical professional at the Health Centre. Equipment needed for an IM injection - Prescribed medicine - 1 syringe - 2 needles (1 for drawing up the drug and 1 for administration – you can use the same size needle for both) - Sharps box (purple lid for testosterone injections and yellow lid for everything else) Below is a list of the syringes and needle sizes required. If you are injecting a drug not listed below then please contact the Health Centre for further advice. These can be purchased online without a prescription. This is normally the most cost-effective way; Amazon have a good stock. If you have any problems purchasing equipment please contact the Health Centre. There is no need to purchase alcohol wipes. PHE (2013) advised that if you are physically clean and in good general health then swabbing prior to injecting is not required. Drug Syringe Size Needle Gauge Needle Length Site Angle 1- 1½ inches (up Testosterone Thigh, upper 2ml 19-25 to 3 inches for 90 (Sustanon) arm, buttocks larger adults) 1-1 ½ inches (up Thigh, upper B12 (IM) 2ml 19-25 to 3 inches for 90 arm, buttocks larger adults) Comes preloaded with 2 syringes, one MMR Thigh 90 for drawing up and one for injecting Where to inject The easiest site when self-administering an IM injection is the middle third of the vastus lateralis muscle of the thigh. -

A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists 4Th Edition

A Guide To Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists 4th Edition Douglas S. Gardenhire, EdD, RRT-NPS, FAARC Dave Burnett, PhD, RRT, AE-C Shawna Strickland, PhD, RRT-NPS, RRT-ACCS, AE-C, FAARC Timothy R. Myers, MBA, RRT-NPS, FAARC Platinum Sponsor Copyright ©2017 by the American Association for Respiratory Care A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists, 4th Edition Douglas S. Gardenhire, EdD, RRT-NPS, FAARC Dave Burnett, PhD, RRT, AE-C Shawna Strickland, PhD, RRT-NPS, RRT-ACCS, AE-C, FAARC Timothy R. Myers, MBA, RRT-NPS, FAARC With a Foreword by Timothy R. Myers, MBA, RRT-NPS, FAARC Chief Business Officer American Association for Respiratory Care DISCLOSURE Douglas S. Gardenhire, EdD, RRT-NPS, FAARC has served as a consultant for the following companies: Westmed, Inc. and Boehringer Ingelheim. Produced by the American Association for Respiratory Care 2 A Guide to Aerosol Delivery Devices for Respiratory Therapists, 4th Edition American Association for Respiratory Care, © 2017 Foreward Aerosol therapy is considered to be one of the corner- any) benefit from their prescribed metered-dose inhalers, stones of respiratory therapy that exemplifies the nuances dry-powder inhalers, and nebulizers simply because they are of both the art and science of 21st century medicine. As not adequately trained or evaluated on their proper use. respiratory therapists are the only health care providers The combination of the right medication and the most who receive extensive formal education and who are tested optimal delivery device with the patient’s cognitive and for competency in aerosol therapy, the ability to manage physical abilities is the critical juncture where science inter- patients with both acute and chronic respiratory disease as sects with art.