2015 Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tropical Cyclone—Induced Heavy Rainfall and Flow in Colima, Western Mexico

Heriot-Watt University Research Gateway Tropical cyclone—Induced heavy rainfall and flow in Colima, Western Mexico Citation for published version: Khouakhi, A, Pattison, I, López-de la Cruz, J, Martinez-Diaz, T, Mendoza-Cano, O & Martínez, M 2019, 'Tropical cyclone—Induced heavy rainfall and flow in Colima, Western Mexico', International Journal of Climatology, pp. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6393 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1002/joc.6393 Link: Link to publication record in Heriot-Watt Research Portal Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: International Journal of Climatology General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via Heriot-Watt Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy Heriot-Watt University has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the content in Heriot-Watt Research Portal complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1 Tropical cyclone - induced heavy rainfall and flow in 2 Colima, Western Mexico 3 4 Abdou Khouakhi*1, Ian Pattison2, Jesús López-de la Cruz3, Martinez-Diaz 5 Teresa3, Oliver Mendoza-Cano3, Miguel Martínez3 6 7 1 School of Architecture, Civil and Building engineering, Loughborough University, 8 Loughborough, UK 9 2 School of Energy, Geoscience, Infrastructure and Society, Heriot Watt University, 10 Edinburgh, UK 11 3 Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Colima, Mexico 12 13 14 15 Manuscript submitted to 16 International Journal of Climatology 17 02 July 2019 18 19 20 21 *Corresponding author: 22 23 Abdou Khouakhi, School of Architecture, Building and Civil Engineering, Loughborough 24 University, Loughborough, UK. -

Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 1997

2440 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 127 Eastern North Paci®c Hurricane Season of 1997 MILES B. LAWRENCE Tropical Prediction Center, National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 15 June 1998, in ®nal form 20 October 1998) ABSTRACT The hurricane season of the eastern North Paci®c basin is summarized and individual tropical cyclones are described. The number of tropical cyclones was near normal. Hurricane Pauline's rainfall ¯ooding killed more than 200 people in the Acapulco, Mexico, area. Linda became the strongest hurricane on record in this basin with 160-kt 1-min winds. 1. Introduction anomaly. Whitney and Hobgood (1997) show by strat- Tropical cyclone activity was near normal in the east- i®cation that there is little difference in the frequency of eastern Paci®c tropical cyclones during El NinÄo years ern North Paci®c basin (east of 1408W). Seventeen trop- ical cyclones reached at least tropical storm strength and during non-El NinÄo years. However, they did ®nd a relation between SSTs near tropical cyclones and the ($34 kt) (1 kt 5 1nmih21 5 1852/3600 or 0.514 444 maximum intensity attained by tropical cyclones. This ms21) and nine of these reached hurricane force ($64 kt). The long-term (1966±96) averages are 15.7 tropical suggests that the slightly above-normal SSTs near this storms and 8.7 hurricanes. Table 1 lists the names, dates, year's tracks contributed to the seven hurricanes reach- maximum 1-min surface wind speed, minimum central ing 100 kt or more. pressure, and deaths, if any, of the 1997 tropical storms In addition to the infrequent conventional surface, and hurricanes, and Figs. -

Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific Ab Sins Nicholas S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School March 2019 Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific aB sins Nicholas S. Grondin Louisiana State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Climate Commons, Meteorology Commons, and the Physical and Environmental Geography Commons Recommended Citation Grondin, Nicholas S., "Climatology, Variability, and Return Periods of Tropical Cyclone Strikes in the Northeastern and Central Pacific asinB s" (2019). LSU Master's Theses. 4864. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4864 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATOLOGY, VARIABILITY, AND RETURN PERIODS OF TROPICAL CYCLONE STRIKES IN THE NORTHEASTERN AND CENTRAL PACIFIC BASINS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Nicholas S. Grondin B.S. Meteorology, University of South Alabama, 2016 May 2019 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my family, especially mom, Mim and Pop, for their love and encouragement every step of the way. This thesis is dedicated to my friends and fraternity brothers, especially Dillon, Sarah, Clay, and Courtney, for their friendship and support. This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and college professors, especially Mrs. -

Lang Hurricane Basic Information Flyer

LANG FLYER INFORMATION BASIC LANG HURRICANE HURRICANE BASIC INFORMATION FLYER FLYER This flyer will try to explain what actions to take when you receive a hurricane watch or warning alert from the INFORMATION INFORMATION National Weather Service for your local area. It also provides tips on what to do before, during, and after a hurricane. https://www.ready.gov/hurricane-toolkit LANG EM WEB PAGE: LANG HURRICANE BASIC BASIC LANG HURRICANE http://geauxguard.la.gov/resources/emergency-management/ 1 Hurricane Basics What Hurricanes are massive storm systems that form over the water and move toward land. Threats from hurricanes include high winds, heavy rainfall, storm surge, coastal and inland flooding, rip currents, and tornadoes. These large storms are called typhoons in the North Pacific Ocean and cyclones in other parts of the world. Where Each year, many parts of the United States experience heavy rains, strong winds, floods, and coastal storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes. Affected areas include all Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastal areas and areas over 100 miles inland, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Hawaii, parts of the Southwest, the Pacific Coast, and the U.S. territories in the Pacific. A significant per cent of fatalities occur outside of landfall counties with causes due to inland flooding. When The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30, with the peak occurring between mid- August and late October. The Eastern Pacific hurricane season begins May 15 and ends November 30. Basic Preparedness Tips •Know where to go. If you are ordered to evacuate, know the local hurricane evacuation route(s) to take and have a plan for where you can stay. -

Hurricane Guide

HOUSTON/GALVESTON HURRICANE GUIDE CAUTION HURRICANE SEASON > TROPICAL STORM BILL 2015 ©2016 CenterPoint Energy 161174 55417_txt_opt_205.06.2016 08:00 AMM Introduction Index of Pages Hurricanes and tropical storms have brought damaging winds, About the Hurricane devastating storm surge, flooding rains and tornadoes to Southeast Page 3 Texas over the years. The 1900 Galveston Hurricane remains the Storm Surge deadliest natural disaster on record for the United States with an Page 4 - 5 estimated 8000 deaths. In 2008 Hurricane Ike brought a deadly storm Zip Zone Evacuation surge to coastal areas and damaging winds that led to extended Pages6-7 power loss to an estimated 3 million customers in southeast Texas. A Winds, Flooding, and powerful hurricane will certainly return but it is impossible to predict Tornadoes Pages8-9 when that will occur. The best practice is to prepare for a hurricane landfall ahead of each hurricane season every year. Preparing Your Home, Business and Boat Pages10-11 This guide is designed to help you prepare for the hurricane season. For Those Who Need There are checklists on what to do before, during and after the storm. Assistance Each hurricane hazard will be described. Maps showing evacuation Page 12 zones and routes are shown. A hurricane tracking chart is included in Preparing Pets and Livestock the middle of the booklet along with the names that will be used for Page 13 upcoming storms. There are useful phone numbers for contacting the Insurance Tips local emergency manager for your area and web links for finding Page 14 weather and emergency information. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2009

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2009 WMO-No. 1055 WMO-No. 1055 © World Meteorological Organization, 2010 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11055-8 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office and the Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; and the National Climatic Data Center, the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, and the National Weather Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Goddard Institute for Space Studies operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Snow and Ice Data Center, United States of America. Other contributors are the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services of Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, -

The Climatology and Nature of Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North

THE CLIMATOLOGY AND NATURE OF TROPICAL CYCLONES OF THE EASTERN NORTH PACIFIC OCE<\N Herbert Loye Hansen Library . U.S. Naval Postgraduate SchdOl Monterey. California 93940 L POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California 1 h i £L O 1 ^ The Climatology and Nature of Trop ical Cy clones of the Eastern North Pacific Ocean by Herbert Loye Hansen Th ssis Advisor : R.J. Renard September 1972 Approved ^oh. pubtic tidLixu, e; dLitnAhiLtlon anturuJitd. TU9568 The Climatology and Nature of Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Ocean by Herbert Loye Hansen Commander, United 'States Navy B.S., Drake University, 1954 B.S., Naval Postgraduate School, 1960 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN METEOROLOGY from the b - duate School y s ^594Q Mo:.--- Lilornia ABSTRACT Meteorological satellites have revealed the need for a major revision of existing climatology of tropical cyclones in the Eastern North Pacific Ocean. The years of reasonably good satellite coverage from 1965 through 1971 provide the data base from which climatologies of frequency, duration, intensity, areas of formation and dissipation and track and speed characteristics are compiled. The climatology of re- curving tracks is treated independently. The probable structure of tropical cyclones is reviewed and applied to this region. Application of these climatolo- gies to forecasting problems is illustrated. The factors best related to formation and dissipation in this area are shown to be sea-surface temperature and vertical wind shear. The cyclones are found to be smaller and weaker than those of the western Pacific and Atlantic oceans. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Hurricane Patricia

HURRICANE TRACKING ADVISORY eVENT™ Hurricane Patricia Information from NHC Advisory 15, 10:00 AM CDT Friday October 23, 2015 Potentially catastrophic Hurricane Patricia is moving northward toward landfall in southwestern Mexico. Maximum sustained winds remain near 200 mph with higher gusts. Patricia is a category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Some fluctuations in intensity are possible today, but Patricia is expected to remain an extremely dangerous category 5 hurricane through landfall. Intensity Measures Position & Heading Landfall (NHC) Max Sustained Wind 200 mph Position Relative to 125 miles SW of Manzanillo Speed: (category 5) Land: 195 miles S of Cabo Corrientes Today between Puerto Est. Time & Region: Vallarta and Manzanillo Min Central Pressure: 880 mb Coordinates: 17.6 N, 105.5 W Trop. Storm Force Est. Max Sustained Wind 155 mph or greater 175 miles Bearing/Speed: N or 5 degrees at 10 mph Winds Extent: Speed: (category 5) Forecast Summary The NHC forecast map (below left) shows Patricia making landfall later today on southwestern Mexico as a major hurricane (category 3+). The windfield map (below right) is based on the NHC’s forecast track which is shown in bold black. To illustrate the uncertainty in Patricia’s forecast track, forecast tracks for all current models are shown in pale gray. Hurricane conditions should reach the hurricane warning area during the next several hours, with the worst conditions likely this afternoon and this evening. Tropical storm conditions are now spreading across portions of the warning area. Hurricane conditions are also possible in the hurricane watch area today. -

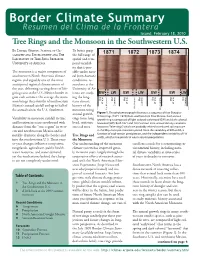

Border Climate Summary

%RUGHU&OLPDWH6XPPDU\ 5HVXPHQGHO&OLPDGHOD)URQWHUD ,VVXHG)HEUXDU\ Tree Rings and the Monsoon in the Southwestern U.S. B" D#$%&' G(%))%$, S*+,,' ,) G&- To better grasp ,-(#.+" #$/ D&0&',.1&$2 #$/ T+& the full range of L#3,(#2,(" ,) T(&&-R%$- R&4&#(*+, spatial and tem- U$%0&(4%2" ,) A(%5,$# poral variabil- ity that is pos- 6e monsoon is a major component of sible under natu- southwestern North America’s climate ral (non-human) regime and arguably one of the most conditions, re- anticipated regional climate events of searchers at the the year, delivering varying doses of life- University of Ar- giving rains to the U.S.-Mexico border re- izona are study- (: /: (: /: (: (: /: gion each summer. On average, the mon- ing the long- Dry Dry Dry soon brings three-fourths of northwestern term climate Wet Wet Wet Wet Winter Winter Winter Winter Mexico’s annual rainfall and up to half of history of the Summer Summer Summer Pre-Monson? Pre-Monsoon? the annual rain in the U.S. Southwest. monsoon using Dry Summer annual growth Figure 1. This photomicrograph illustrates a sequence of four Douglas- !r tree rings (1871–1874) from southwestern New Mexico. Each annual Variability in monsoon rainfall in time rings from long- growth ring is composed of light-colored earlywood (EW) and dark-colored and location increases northward with lived, moisture- latewood (LW). Both 1871 and 1872 contain intra-annual density variations distance from the “core region” in west- stressed trees. known as “false rings,” which are probably related to reduced soil moisture ern and northwestern Mexico and is in the May–June pre-monsoon period. -

9. East Pacific Easterly Wave Genesis Experiment

9. East Pacific Easterly Wave Genesis Experiment Principle Investigators: Ghassan Alaka (HRD) Adam Rydbeck (NRL) Eric Maloney (CSU) Links to IFEX Goals: Goal 1: Collect observations that span the TC life cycle in a variety of environments for model initialization and evaluation; Goal 3: Improve understanding of the physical processes important in intensity change for a TC at all stages of its lifecycle. Significance & Background: Many studies have hypothesized that African easterly waves (EWs) serve as seed disturbances for East Pacific tropical cyclones (TCs) (e.g., Avila and Pasch 1992). However, it is often difficult to track African EWs crossing Central America and entering the East Pacific basin. In addition, African EWs may not be necessary to initiate EWs in the East Pacific. Several mechanisms for the in situ generation of EWs in the East Pacific have been proposed: 1) breakdown of the inter-tropical convergence zone (Ferriera and Schubert 1997), 2) barotropically unstable gap jets (Mozer and Zehnder 1996), 3) inertial instabilities from cross-equatorial pressure gradients (Toma and Webster 2010), 4) growth of vorticity noise by barotropic conversion in favorable basic states (Maloney and Hartmann 2001, Hartmann and Maloney 2001), and 5) upscale vorticity organization from diurnal convection in the Panama Bight (Rydbeck et al. 2016). This last mechanism for EW generation, proposed by Rydbeck et al. (2016), is the focus of this experiment. East Pacific EW initiation can occur near the coasts of Panama and Colombia, with little or no preceding signal propagating from the Atlantic Ocean (Rydbeck and Maloney 2014). The Panama Bight has the highest occurrence of organized deep convection on the planet based on the NOAA Highly Reflective Cloud dataset (Kilonsky and Ramage 1976). -

HURRICANE OLAF (EP192015) 15 – 27 October 2015

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE OLAF (EP192015) 15 – 27 October 2015 Eric S. Blake National Hurricane Center Jon Jelsema Central Pacific Hurricane Center 1 6 September 2016 NOAA GOES-15 INFARED SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE OLAF AT 0630 UTC 20 OCTOBER 2015. Olaf was an unusually long-lasting October hurricane that formed much farther southwest than average and stayed out at sea. Olaf has the distinction of being the only tropical cyclone on record to move from the eastern Pacific to the central Pacific and back again. 1 Original report date 9 February 2016. Report updated to include CPHC verification 6 September 2016. Hurricane Olaf 2 Hurricane Olaf 15 – 27 OCTOBER 2015 SYNOPTIC HISTORY The genesis of Olaf can be traced to a wave that left the west African coast on 24 September. The wave produced a fair amount of convection for a few days, but lost all thunderstorm activity in the central Atlantic on 27 September. After moving slowly westward during the next several days, the wave entered the eastern Pacific on 7 October. Convection greatly increased the next day, and a broad low formed by late on 9 October at a low latitude south of 10°N. The thunderstorm activity, however, was generally limited over the next several days, and the low remained broad while it moved westward. On 14 October, convection increased and the low became better defined, leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 0000 UTC 15 October about 860 n mi south-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. The “best track” chart of the tropical cyclone’s path is given in Fig. -

State of the Climate in 2015

STATE OF THE CLIMATE IN 2015 Special Supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society Vol. 97, No. 8, August 2016 STATE OF THE CLIMATE IN 2015 Editors Jessica Blunden Derek S. Arndt Chapter Editors Howard J. Diamond Jeremy T. Mathis Jacqueline A. Richter-Menge A. Johannes Dolman Ademe Mekonnen Ahira Sánchez-Lugo Robert J. H. Dunn A. Rost Parsons Carl J. Schreck III Dale F. Hurst James A. Renwick Sharon Stammerjohn Gregory C. Johnson Kate M. Willett Technical Editors Kristin Gilbert Tom Maycock Susan Osborne Mara Sprain AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY COVER CREDITS: FRONT: Reproduced by courtesy of Jillian Pelto Art/University of Maine Alumnus, Studio Art and Earth Science — Landscape of Change © 2015 by the artist. BACK: Reproduced by courtesy of Jillian Pelto Art/University of Maine Alumnus, Studio Art and Earth Science — Salmon Population Decline © 2015 by the artist. Landscape of Change uses data about sea level rise, glacier volume decline, increasing global temperatures, and the increas- ing use of fossil fuels. These data lines compose a landscape shaped by the changing climate, a world in which we are now living. (Data sources available at www.jillpelto.com/landscape-of-change; 2015.) Salmon Population Decline uses population data about the Coho species in the Puget Sound, Washington. Seeing the rivers and reservoirs in western Washington looking so barren was frightening; the snowpack in the mountains and on the glaciers supplies a lot of the water for this region, and the additional lack of precipitation has greatly depleted the state’s hydrosphere. Consequently, the water level in the rivers the salmon spawn in is very low, and not cold enough for them.