Hurricane Preparedness Guide (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 1-B Cause & Impact of Landfalling Tropical Cyclone

Part 1-b Cause & Impact of Landfalling Tropical Cyclone Rainfall & River Flooding • In addition to high winds & storm surge, all tropical storms can produce torrential rains causing massive flooding & trigger landslides and debris floods • Catastrophic flash flooding may occur as a result of intense rainfall over a relatively short duration. Longer duration storms, say a few days, can be equally devastating. 2 River flooding associated with heavy rainfall from tropical cyclones Flood stages & inundation maps • Rain-triggered flooding is not confined to coastal areas. The reach of a large tropical storm can cause flooding well inland, especially along the estuaries. • Beneficial contributions of tropical cyclones: rainfall for needed water supply in the region; and maintenance of global heat balance 5 Cases of landfalling of catastrophic tropical cyclones • Hurricane Andrew , August 24, 1993- Florida • Hurricane Allison , June 5-9, 2001- Houston and TX and LA coasts • Hurricane Katrina , Aug 29, 2005- New Orleans & LA and TX coasts • Hurricane Mitch , Oct 26- Nov 5, Honduras, Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala • Typhoon Morakot , August 3-10, 2009, Taiwan • Typhoon Ketsana , Sept 23-30, 2009, Manila, Philippine , Vietnam & Cambodia 6 Hurricane Andrew (Aug24,1993) 7 Hurricane Andrew (Aug24,1993) Source: Report on Hurricane Andrew Storm Summary & Impacts on Florida Beaches, by USACE & Florida DNR, May 1993 Pressure zones, wind zones and storm surge contour 9 Surge at landfall & waves height Storm surges Wave Heights 10 Impact of gusts on homes 11 Impacts on beaches of Florida 12 Erosion and accretion of beach profiles 13 Hurricane Allison, June 5-9, 2001 * Hurricane Allison’s swath of rainfall – 25-50 cm or more rainfall in coastal TX & LA for nearly 6 days. -

Observed Hurricane Wind Speed Asymmetries and Relationships to Motion and Environmental Shear

1290 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 142 Observed Hurricane Wind Speed Asymmetries and Relationships to Motion and Environmental Shear ERIC W. UHLHORN NOAA/AOML/Hurricane Research Division, Miami, Florida BRADLEY W. KLOTZ Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, Florida TOMISLAVA VUKICEVIC,PAUL D. REASOR, AND ROBERT F. ROGERS NOAA/AOML/Hurricane Research Division, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 6 June 2013, in final form 19 November 2013) ABSTRACT Wavenumber-1 wind speed asymmetries in 35 hurricanes are quantified in terms of their amplitude and phase, based on aircraft observations from 128 individual flights between 1998 and 2011. The impacts of motion and 850–200-mb environmental vertical shear are examined separately to estimate the resulting asymmetric structures at the sea surface and standard 700-mb reconnaissance flight level. The surface asymmetry amplitude is on average around 50% smaller than found at flight level, and while the asymmetry amplitude grows in proportion to storm translation speed at the flight level, no significant growth at the surface is observed, contrary to conventional assumption. However, a significant upwind storm-motion- relative phase rotation is found at the surface as translation speed increases, while the flight-level phase remains fairly constant. After removing the estimated impact of storm motion on the asymmetry, a significant residual shear direction-relative asymmetry is found, particularly at the surface, and, on average, is located downshear to the left of shear. Furthermore, the shear-relative phase has a significant downwind rotation as shear magnitude increases, such that the maximum rotates from the downshear to left-of-shear azimuthal location. -

Wind Speed-Damage Correlation in Hurricane Katrina

JP 1.36 WIND SPEED-DAMAGE CORRELATION IN HURRICANE KATRINA Timothy P. Marshall* Haag Engineering Co. Dallas, Texas 1. INTRODUCTION According to Knabb et al. (2006), Hurricane Katrina Mehta et al. (1983) and Kareem (1984) utilized the was the costliest hurricane disaster in the United States to concept of wind speed-damage correlation after date. The hurricane caused widespread devastation from Hurricanes Frederic and Alicia, respectively. In essence, Florida to Louisiana to Mississippi making a total of three each building acts like an anemometer that records the landfalls before dissipating over the Ohio River Valley. wind speed. A range of failure wind speeds can be The storm damaged or destroyed many properties, determined by analyzing building damage whereas especially near the coasts. undamaged buildings can provide upper bounds to the Since the hurricane, various agencies have conducted wind speeds. In 2006, WSEC developed a wind speed- building damage assessments to estimate the wind fields damage scale entitled the EF-scale, named after the late that occurred during the storm. The National Oceanic Dr. Ted Fujita. The author served on this committee. and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, 2005a) Wind speed-damage correlation is useful especially conducted aerial and ground surveys and published a when few ground-based wind speed measurements are wind speed map. Likewise, the Federal Emergency available. Such was the case in Hurricane Katrina when Management Agency (FEMA, 2006) conducted a similar most of the automated stations failed before the eye study and produced another wind speed map. Both reached the coast. However, mobile towers were studies used a combination of wind speed-damage deployed by Texas Tech University (TTU) at Slidell, LA correlation, actual wind measurements, as well as and Bay St. -

Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 1997

2440 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 127 Eastern North Paci®c Hurricane Season of 1997 MILES B. LAWRENCE Tropical Prediction Center, National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 15 June 1998, in ®nal form 20 October 1998) ABSTRACT The hurricane season of the eastern North Paci®c basin is summarized and individual tropical cyclones are described. The number of tropical cyclones was near normal. Hurricane Pauline's rainfall ¯ooding killed more than 200 people in the Acapulco, Mexico, area. Linda became the strongest hurricane on record in this basin with 160-kt 1-min winds. 1. Introduction anomaly. Whitney and Hobgood (1997) show by strat- Tropical cyclone activity was near normal in the east- i®cation that there is little difference in the frequency of eastern Paci®c tropical cyclones during El NinÄo years ern North Paci®c basin (east of 1408W). Seventeen trop- ical cyclones reached at least tropical storm strength and during non-El NinÄo years. However, they did ®nd a relation between SSTs near tropical cyclones and the ($34 kt) (1 kt 5 1nmih21 5 1852/3600 or 0.514 444 maximum intensity attained by tropical cyclones. This ms21) and nine of these reached hurricane force ($64 kt). The long-term (1966±96) averages are 15.7 tropical suggests that the slightly above-normal SSTs near this storms and 8.7 hurricanes. Table 1 lists the names, dates, year's tracks contributed to the seven hurricanes reach- maximum 1-min surface wind speed, minimum central ing 100 kt or more. pressure, and deaths, if any, of the 1997 tropical storms In addition to the infrequent conventional surface, and hurricanes, and Figs. -

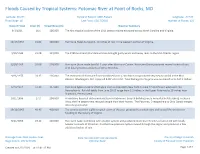

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD Latitude: 39.274 Period of Record: 1889-Present Longitude: -77.543 Flood Stage: 16 Last Flood: 12/17/2018 Number of Floods: 121 Date of Flood Crest (ft) Streamflow (cfs) Weather Summary 9/1/1911 16.1 106,000 The first tropical cyclone of the 1911 season moved eastward across North Carolina and Virginia. 10/17/1954 21.02 130,000 Hurricane Hazel dumped 6- 10 inches of rain in the western portion of Virginia. 9/20/1945 21.98 139,000 The 1945 Southeast Florida Hurricane brought gusty winds and heavy rains to the Mid-Atlantic region. 8/20/1955 29.08 214,000 Hurricane Diane made landfall 5 days after Hurricane Connie. Hurricane Diane produced several inches of rain with locally heavier amounts of 10 to 20 inches. 9/26/1975 24.35 126,000 The remnants of Hurricane Eloise combined with a cold front and produced very heavy rainfall in the Mid- Atlantic. Washington, D.C. reported 9.08" of rainfall. Total damage for Virginia was estimated to be $17.2 million. 6/23/1972 37.43 347,000 Hurricane Agnes made landfall again over southeastern New York on June 22 and moved westward into Pennsylvania. Rainfall totals from June 20-25 range from 2-3 inches in the Upper Potomac to 18 inches near Shamokin, Pennsylvania. 10/1/1896 27.2 204,000 A hurricane knocked out communication in Richmond. Several buildings were unroofed in Petersburg. In Buena Vista, the fire department rescued people from their homes. -

FEMA FOIA Log – 2018

Mirandra Abrams, Monique any and all records concerning clients. Kindly provide our office with 10/4/2017 Sambursky a complete copy of clients entire file as it pertains as it pertains to Slone Sklarin Inquiry Number (b) (6) ; Voucher Number (b) (6) ; Payee Verveniotis Reference Number (b) (6) in your possession. 2017-FEFO-02138 - Masters, Mark all contract documents related to temporary staffing services 10/5/2017 contracts for emergency call center support for FEMA in the last five 2017-FEFO-02177 (5) years 2017-FEFO-02187 - (b) (6) all files, correspondence, or other records concerning yourself 10/6/2017 Dallas News Benning, Tom 1) All active FEMA contracts for manufactured housing units. 2) All 10/13/2017 active FEMA individual assistance/technical assistance contracts (IATACs). 3) All pre-event contracts for debris removal that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 4) All pre-event contracts for housing assistance that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 5) All noncompetitive disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017. 6) All non-local disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017, including the written justification 2017-FEFO-02214 for choosing a non-local vendor. FCI Keys, Clay a copy of any and all records related to [FEMA's] response to 10/23/2017 SEAGOVILLE hurricane Katrina, including all memoranda, communications and records of any kind and from any source from August 29, 2005 to 2012. (Date Range for Record Search: From 8/29/2005 To 2017-FEFO-02239 12/1/2012) - (b) (6) Any files related to yourself (Date Range for Record Search: From 10/24/2017 2017-FEFO-02240 1/1/2000 To 9/11/2017) - McClain, Don every individual who has requested assistance by FEMA from both 10/31/2017 Hurricane Irma and Harvey. -

Wasn't That a Mighty Day Galveston Hurricane Song Prompt Folk Song

Wasn’t That a Mighty Day Galveston Hurricane Song Prompt Folk song lyrics are often flawed with respect to facts. This results from generations passing along verses which, though fraught with emotion, are sometimes lacking facts. Also, needing rhyming words may inject error into historical accuracy. The purpose of this prompt is to assess the accuracy of the lyrics of a popular song about the 1900 Galveston hurricane, Wasn’t That a Mighty Day? There are at least six errors/exaggerations among the verses listed below. After reading the account below, write a one page double-spaced essay describing your findings. I remember one September, When storm winds swept the town; The high tide from the ocean, Lord, Put water all around. Chorus: Wasn't that a mighty day, A mighty day A mighty day, Great God, that morning When the storm winds swept the town! There was a sea-wall there in Galveston To keep the waters down, But the high tide from the ocean, Lord, Put water in the town. The trumpets warned the people, 'You'd better leave this place!' But they never meant to leave their homes Till death was in their face. The trains they all were loaded With people leaving town; The tracks gave way to the ocean, Lord, And the trains they went on down. Great Galveston Storm Article Paraphrased from Wikipedia Information At the end of the 19th century, the city of Galveston, Texas was a booming city with a population of approximately 38,000 residents. Its position on the natural harbor of Galveston Bay along the Gulf of Mexico made it the center of trade and the biggest city in the state of Texas. -

Hurricane Knowledge

Hurricane Knowledge Storm conditions can vary on the intensity, size and even the angle which the tropical cyclone approaches your area, so it is vital you understand what the forecasters and news reporters are telling you. Tropical Depressions are cyclones with winds of 38 mph. Tropical Storms vary in wind speeds from 39-73 mph while Hurricanes have winds 74 mph and greater. Typically, the upper right quadrant of the storm (the center wrapping around the eye) is the most intense portion of the storm. The greatest threats are damaging winds, storm surge and flooding. This is in part why Hurricane Katrina was so catastrophic when bringing up to 28-foot storm surges onto the Louisiana and Mississippi coastlines. A Tropical Storm Watch is when tropical storm conditions are possible in the area. A Hurricane Watch is when hurricane conditions are possible in the area. Watches are issued 48 hours in advance of the anticipated onset of tropical storm force winds. A Tropical Storm Warning is when tropical storm conditions are expected in the area. A Hurricane Warning is when hurricane conditions are expected in the area. Warnings are issued 36 hours in advance of tropical storm force winds. Here are a few more terms used when discussing hurricanes: Eye: Clear, sometimes well-defined center of the storm with calmer conditions. Eye Wall: Surrounding the eye, contains some of the most severe weather of the storm with the highest wind speed and largest precipitation. Rain Bands: Bands coming off the cyclone that produce severe weather conditions such as heavy rain, wind and tornadoes. -

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events

Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events Final Report December 22, 2015 Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events BACKGROUND A “classic late-season…extraordinarily large hurricane,” 1 Sandy was the 18th named tropical cyclone of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season. It made landfall along the mid-Atlantic coast near Atlantic City, NJ about 6:30 pm on October 29, 2012 as a Category 1 hurricane with 80- mph maximum sustained winds. But due to its extensive breadth (winds above 40 mph (tropical storm force) stretched 900 miles), Sandy’s real damage was done by a calamitous storm surge that merged with a high tide to produce a storm surge, primarily pounding the New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut coastlines (Figure 1). The United States Geological Survey measured water levels on Staten Island, New York at almost eight feet above ground level. Even after the storm moved on, it impacted inland states, including Ohio, West Virginia, and Indiana, with high winds, soaking rains, and even heavy snow in the Appalachians. 2,3 Very High: > 10,000 people exposed to surge High: 500 – 10,000 people exposed to surge OR > $100 million in wind damage OR > 8” rain Moderate: 100 – 500 people exposed to surge OR $10 - $100 million in wind damage OR 4” - 8” rain Low: no surge impacts OR < $10 million in wind damage OR < 4” rain Figure 1. 2 FEMA Hurricane Sandy Impact Analysis The consequences of the storm’s destructive power were significant. -

Lang Hurricane Basic Information Flyer

LANG FLYER INFORMATION BASIC LANG HURRICANE HURRICANE BASIC INFORMATION FLYER FLYER This flyer will try to explain what actions to take when you receive a hurricane watch or warning alert from the INFORMATION INFORMATION National Weather Service for your local area. It also provides tips on what to do before, during, and after a hurricane. https://www.ready.gov/hurricane-toolkit LANG EM WEB PAGE: LANG HURRICANE BASIC BASIC LANG HURRICANE http://geauxguard.la.gov/resources/emergency-management/ 1 Hurricane Basics What Hurricanes are massive storm systems that form over the water and move toward land. Threats from hurricanes include high winds, heavy rainfall, storm surge, coastal and inland flooding, rip currents, and tornadoes. These large storms are called typhoons in the North Pacific Ocean and cyclones in other parts of the world. Where Each year, many parts of the United States experience heavy rains, strong winds, floods, and coastal storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes. Affected areas include all Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastal areas and areas over 100 miles inland, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Hawaii, parts of the Southwest, the Pacific Coast, and the U.S. territories in the Pacific. A significant per cent of fatalities occur outside of landfall counties with causes due to inland flooding. When The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30, with the peak occurring between mid- August and late October. The Eastern Pacific hurricane season begins May 15 and ends November 30. Basic Preparedness Tips •Know where to go. If you are ordered to evacuate, know the local hurricane evacuation route(s) to take and have a plan for where you can stay. -

Urbanization Exacerbated the Rainfall and Flooding Caused by Hurricane Harvey and Tropical Storm Allison

Urbanization exacerbated the rainfall and flooding caused by hurricane Harvey and tropical storm Allison Wei Zhang IIHR-Hydroscience & Engineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City Hurricanes are formed in the warm ocean and make landfall over coastal regions occasionally. NASA 2 Hurricanes are warm-core low-pressure systems with destructive winds and torrential rainfall. Harvey in 2017 Katrina in 2005 100+ casualties 1,800+ casualties $125+ billion in damage $160+ billion in damage National Weather Service 3 Harvey stayed in Texas for several days. The reason for its stalling movement is still under investigation. 4 Record-breaking hurricane Harvey poured more than 1 meter rainfall over some parts of Houston. 休斯顿 Houston Stage IV Radar Products 5 Extreme precipitation and flash flooding caused by hurricane Harvey have led to major damages to Houston and surrounding areas. Associated Press CNN 6 Research on Harvey Rainfall (Impacts of anthropogenic forcing) • Assessing the present and future probability of Hurricane Harvey's rainfall (Emanuel 2018) • Quantitative attribution of climate effects on Hurricane Harvey's extreme rainfall in Texas (Wang et al. 2018) • Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017 (Van Oldenborgh et al. 2018) • Hurricane Harvey links to ocean heat content and climate change adaptation (Trenberth et al. 2018) 7 Climate change increased the probability of Harvey rainfall events. (Van Oldenborgh et al. 2018) 8 Again, climate change increased the probability of Harvey rainfall events. Emanuel, 2017, PNAS But, I examined Harvey rainfall from a different perspective … 9 What was the role played by buildings in Houston in changing the rainfall associated with hurricane Harvey? Before Hurricane Harvey After Hurricane Harvey 10 Oke et al.