Lessons Learned from Hurricane Sandy and Recommendations for Improved Healthcare and Public Health Response and Recovery for Future Catastrophic Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

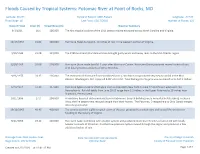

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD Latitude: 39.274 Period of Record: 1889-Present Longitude: -77.543 Flood Stage: 16 Last Flood: 12/17/2018 Number of Floods: 121 Date of Flood Crest (ft) Streamflow (cfs) Weather Summary 9/1/1911 16.1 106,000 The first tropical cyclone of the 1911 season moved eastward across North Carolina and Virginia. 10/17/1954 21.02 130,000 Hurricane Hazel dumped 6- 10 inches of rain in the western portion of Virginia. 9/20/1945 21.98 139,000 The 1945 Southeast Florida Hurricane brought gusty winds and heavy rains to the Mid-Atlantic region. 8/20/1955 29.08 214,000 Hurricane Diane made landfall 5 days after Hurricane Connie. Hurricane Diane produced several inches of rain with locally heavier amounts of 10 to 20 inches. 9/26/1975 24.35 126,000 The remnants of Hurricane Eloise combined with a cold front and produced very heavy rainfall in the Mid- Atlantic. Washington, D.C. reported 9.08" of rainfall. Total damage for Virginia was estimated to be $17.2 million. 6/23/1972 37.43 347,000 Hurricane Agnes made landfall again over southeastern New York on June 22 and moved westward into Pennsylvania. Rainfall totals from June 20-25 range from 2-3 inches in the Upper Potomac to 18 inches near Shamokin, Pennsylvania. 10/1/1896 27.2 204,000 A hurricane knocked out communication in Richmond. Several buildings were unroofed in Petersburg. In Buena Vista, the fire department rescued people from their homes. -

FEMA FOIA Log – 2018

Mirandra Abrams, Monique any and all records concerning clients. Kindly provide our office with 10/4/2017 Sambursky a complete copy of clients entire file as it pertains as it pertains to Slone Sklarin Inquiry Number (b) (6) ; Voucher Number (b) (6) ; Payee Verveniotis Reference Number (b) (6) in your possession. 2017-FEFO-02138 - Masters, Mark all contract documents related to temporary staffing services 10/5/2017 contracts for emergency call center support for FEMA in the last five 2017-FEFO-02177 (5) years 2017-FEFO-02187 - (b) (6) all files, correspondence, or other records concerning yourself 10/6/2017 Dallas News Benning, Tom 1) All active FEMA contracts for manufactured housing units. 2) All 10/13/2017 active FEMA individual assistance/technical assistance contracts (IATACs). 3) All pre-event contracts for debris removal that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 4) All pre-event contracts for housing assistance that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 5) All noncompetitive disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017. 6) All non-local disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017, including the written justification 2017-FEFO-02214 for choosing a non-local vendor. FCI Keys, Clay a copy of any and all records related to [FEMA's] response to 10/23/2017 SEAGOVILLE hurricane Katrina, including all memoranda, communications and records of any kind and from any source from August 29, 2005 to 2012. (Date Range for Record Search: From 8/29/2005 To 2017-FEFO-02239 12/1/2012) - (b) (6) Any files related to yourself (Date Range for Record Search: From 10/24/2017 2017-FEFO-02240 1/1/2000 To 9/11/2017) - McClain, Don every individual who has requested assistance by FEMA from both 10/31/2017 Hurricane Irma and Harvey. -

Tropical Topics Week 2021 NWS Florida &

5/21/2021 Tornado Recognition, Impacts & Messaging Scott Spratt; NWS Melbourne | Robert Molleda; NWS Miami 1 TC Tornadoes Tornado Recognition, Impacts & Messaging 2 1 5/21/2021 TC Tornadoes Today’s Presentation Topics • Previous Events • Climatology/Favorable Patterns • Worse Case Scenario • Threat/Impact Messaging Hurricane Irma September 10, 2017 EF-1 Tornado 1124 am | Indialantic, FL • Future Improvements 3 TC Tornadoes What is the relative threat? Which tropical cyclone hazard poses the greatest threat? A. Wind B. Storm Surge Flooding C. Heavy Rainfall Flooding D. Tornadoes E. It depends – on the particular storm/hurricane; and on where you are located 4 2 5/21/2021 The TC Tornado Hazard can be Significant A Specific Example – Tropical Storm Gordon (1994) T Barefoot Bay, FL November 16, 1994 Nearly 500 MH damaged Including 62 destroyed Tropical storm center at 1 Fatality; 40 injuries time of tornado T Tornado location 5 TC Tornadoes Threat Recognition, Impacts & Messaging The primary Tropical Cyclone (TC) tornado challenges are. 1) Predicting tornadoes outside the area where people are prepared for hurricane force winds; or prior to the damaging hurricane wind onset. 2) Predicting tornadoes from weaker systems where tornadoes may pose the greatest threat. 3) Minimizing the amount of over-warning. 4) Successfully Messaging #1-3 6 3 5/21/2021 TC Tornadoes Addressing the primary challenges • Threat Assessment • Impact Recognition • Effective Messaging 7 TC Tornado Development Diagnosing the local tornado hazard • Certain weather factors enhance the tornado potential of landfalling or paralleling systems: ✓ Strong low-level wind shear (maximized in right-front quadrant). ✓ Pockets of dry air (enhance instability; isolated cells). -

Voters Guide

VOTING ENDS September 30, 2017 FREE 2018 VOTERS GUIDE VOTE FOR THE BEST BUSINESSES IN BROOKLYN NOMINATED BY YOU! 2,000+ BUSINESSES 175+ CATEGORIES PRODUCED BY SCHNEPS COMMUNICATIONS FOLLOW US ENJOY THE FREE LIFE. FREE CHECKING AND A FREE GIFT! Get a free gift1 when you you open any Perfectly Free Checking account. 800.321.DIME (3463) • dime.com Dime Community Bank 1 We reserve the right to substitute a gift of similar value. Free gift provided at time of account opening. Free gift may be reported on a 1099-INT or 1099-MISC. Limit of one new checking account opened per customer receiving a free gift. Other fees such as for non-sufficient funds, overdraft, etc. may apply. See Schedule of Service Charges for details. Bank rules and regulations apply. Minimum opening deposit is only $25. Ask us for details. 2 BEST OF BROOKLYN 2018 • VOTERS GUIDE • BESTOFBK.COM Congratulations to all of the businesses that have been nominated for the 2018 Dime Best of Brooklyn awards. The nominees were selected by Brooklyn residents and each exemplifies excellence in the category for which they were nominated. Dime Community Bank is proud to be the Naming Sponsor of the Dime Best of Brooklyn program. In partnering with Best of Brooklyn, we are delighted to showcase and highlight this magnificent borough’s small businesses, a core part of our vibrant and growing communities. The voting period is already underway and we look forward to crowning the Dime Best of Brooklyn winners for 2018. Just like the businesses nominated, Dime has deep Brooklyn roots tracing our history back to 1864 in Williamsburg. -

School of Nursing 2012–2013

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Nursing 2012–2013 School of Nursing 2012–2013 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 108 Number 15 September 5, 2012 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 108 Number 15 September 5, 2012 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849 (voice), 203.432.9388 The closing date for material in this bulletin was August 1, 2012. -

Hurricane & Tropical Storm

5.8 HURRICANE & TROPICAL STORM SECTION 5.8 HURRICANE AND TROPICAL STORM 5.8.1 HAZARD DESCRIPTION A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (NOAA, 2013). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. The average wind speeds for tropical storms and hurricanes are listed below: . A tropical depression has a maximum sustained wind speeds of 38 miles per hour (mph) or less . A tropical storm has maximum sustained wind speeds of 39 to 73 mph . A hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; similar storms in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean are called cyclones. A major hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 111 mph or higher (NOAA, 2013). Over a two-year period, the United States coastline is struck by an average of three hurricanes, one of which is classified as a major hurricane. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and tropical depressions may pose a threat to life and property. These storms bring heavy rain, storm surge and flooding (NOAA, 2013). The cooler waters off the coast of New Jersey can serve to diminish the energy of storms that have traveled up the eastern seaboard. -

Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

FLORIDA HURRICANES AND TROPICAL STORMS 1871-1995: An Historical Survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams '+wcCopy~~ I~BN 0-912747-08-0 Florida SeaGrant College is supported by award of the Office of Sea Grant, NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce,grant number NA 36RG-0070, under provisions of the NationalSea Grant College and Programs Act of 1966. This information is published by the Sea Grant Extension Program which functionsas a coinponentof the Florida Cooperative Extension Service, John T. Woeste, Dean, in conducting Cooperative Extensionwork in Agriculture, Home Economics, and Marine Sciences,State of Florida, U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, U.S. Departmentof Commerce, and Boards of County Commissioners, cooperating.Printed and distributed in furtherance af the Actsof Congressof May 8 andJune 14, 1914.The Florida Sea Grant Collegeis an Equal Opportunity-AffirmativeAction employer authorizedto provide research, educational information and other servicesonly to individuals and institutions that function without regardto race,color, sex, age,handicap or nationalorigin. Coverphoto: Hank Brandli & Rob Downey LOANCOPY ONLY Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms 1871-1995: An Historical survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams Division of Marine and Environmental Systems, Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, FL 32901 Technical Paper - 71 June 1994 $5.00 Copies may be obtained from: Florida Sea Grant College Program University of Florida Building 803 P.O. Box 110409 Gainesville, FL 32611-0409 904-392-2801 II Our friend andcolleague, Fred Doehringpictured below, died on January 5, 1993, before this manuscript was completed. Until his death, Fred had spent the last 18 months painstakingly researchingdata for this book. -

28/38 Bwn/Awp

BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 18pBWN, 16pBRZ •Vol. 28, No. 38 •Saturday, September 24, 2005 • FREE MAKE IT SMALLER Marty downsizes his support for Ratner By Jess Wisloski homeowners with the use of eminent do- The Brooklyn Papers main for private gain. Reform Party and Libertarian Party candidate Gary Popkin Borough President Marty Marko- charged collusion between elected officials witz has urged that developer Bruce and private-party interests in the project. Ratner downsize his Atlantic Yards Attorney Theodore Alatsas, running on mega-development, a project vigorous- the Republican and Conservative ballots, ly supported by Markowitz since 2003. supports the project. “We do have to scale down this project,” Awave of applause followed Marko- Markowtiz said during a debate Monday witz’s call for the downscaling. among Markowitz and three challengers The borough president has long been an seeking his job in the November election. outspoken advocate of bringing a pro- “There is no question, in terms of the sports team to Brooklyn and has not fal- project, in terms of the housing, and in tered in his support for Ratner’s larger terms of the buildings, it is time for all of project, would be built east of the intersec- Thor Equities us to join together to work cooperatively tion of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. and downscale the project and to make it “I was as surprised as probably every- more reflective of the needs and aspira- body in the room; I don’t think I’d ever tions of those of the environment it’s in.” heard those words uttered by him,” said His comments came after two of Fort Greene Association Chairman Phillip Markowitz’s rivals voiced their opposition Kellogg following Markowitz’s com- to the way in which Ratner’s bid to erect ments. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 16, 2015, Designation List 482 LP-2519

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 16, 2015, Designation List 482 LP-2519 M.H. RENKEN DAIRY COMPANY, Office Building, 582-584 Myrtle Avenue (aka 192 Classon Avenue), and Engine Room Building, 580 Myrtle Avenue, Brooklyn Built: Office Building, 1932; Koch & Wagner, architects Engine Room Building, circa 1860, architect not determined; main facade 1936-37, Koch & Wagner, architects Landmark Site: Borough of Brooklyn, Tax Map Block 1909, Lot 32 in its entirety and Lots 1001 and 1002 in part, consisting of that portion of Lots 1001 and 1002 lying north of a line beginning at a point on the eastern boundary line of Lots 1001 and 1002 that is 61.21 feet south of the northern boundary line of Lots 1001 and 1002, thence running westerly, parallel with the northern boundary line of Lots 1001 and 1002, to a point on the western boundary line of Lots 1001 and 1002. On June 2, 2015, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the M.H. Renken Dairy Company Office and Engine Room Buildings and the proposed designation of the related Landmark site (Item No. 3). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Two people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the Historic Districts Council and New York Landmarks Conservancy. The Commission also received letters in favor of designation from Council Member Laurie A. Cumbo, Community Board 2, and the Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. This followed two earlier hearings in which the two buildings were heard individually. -

Hurricane Committee Considers Lessons from Sandy Lessons

Hurricane Committee Considers Lessons from Sandy Lessons learned from Hurricane Sandy are high on the agenda of a meeting convened by the World Meteorological Organization to review the 2012 tropical cyclone season in the Atlantic and eastern North Pacific and prepare for the forthcoming season. The Hurricane Committee of WMO Regional Association IV (North and Central America and the Caribbean) meets in Curacao 8-12 April to discuss how to strengthen warning services and regional coordination to protect lives and property. The 2012 Atlantic hurricane season was marked by above-average tropical cyclone activity with the formation of 19 tropical storms, of which ten became hurricanes. The numbers of tropical storms and hurricanes were each above the long-term average (1981–2010) of 12 and 6, respectively. Two of the hurricanes – Michael and Sandy – strengthened into major hurricanes (Category 3 or stronger on the Saffir- Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale), according to a review of the past hurricane season prepared by WMO’s Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) Miami. The U. S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) serves as the RSMC for WMO Regional Association IV. WMO Deputy Secretary-General Jerry Lengoasa said the massive impact of Hurricane Sandy on the Caribbean and United States had heightened international awareness about the threat of tropical cyclones in the region. “This Hurricane, which caused or contributed to the deaths of almost 300 people and resulted in total economic losses of over 75 billion US dollars, has left us many important lessons to learn in forecasting, early warning and communication,” Mr Lengoasa told the opening session of the Hurricane Committee. -

Hurricane Preparedness Guide (PDF)

hurricanes... Unleashing Nature’s Fury FEMA Hurricane Floyd, 1999/NOAA A PREPAREDNESS GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service Revised August 2001 What is a Hurricane? The term hurricane has its origin in the indigenous religions of old civilizations. The Mayan storm god A hurricane is a type of tropical cyclone–an organized was named Hunraken. A god considered evil by rotating weather system that develops in the tropics. the Taino people of the Caribbean was called Huracan. Hurricanes rotate counterclockwise in the Northern Hurricanes may not be considered evil but they Hemisphere. Tropical cyclones are classified as follows: are one of nature’s most powerful storms. Their ■ Tropical Depression—An organized system of potential for loss of life and destruction of property persistent clouds and thunderstorms with a closed is tremendous. Those in hurricane-prone areas low-level circulation and maximum sustained winds need to be of 38 mph (33 knots) or less. prepared for hurricanes and ■ Tropical Storm—An organized system of strong tropical storms. thunderstorms with a well defined circulation and Even inland areas, maximum sustained winds of 39 to 73 mph well away from (34-63 knots). the coastline, ■ Hurricane—An intense tropical weather system can experience with a well defined circulation and sustained winds destructive winds, of 74 mph (64 knots) or higher. In the western North tornadoes and Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons, and similar floods from storms in the Indian Ocean are called cyclones. tropical storms and hurricanes. Hurricane Iniki/NOAA 1998 Atlantic Ocean Hurricane Season Summary/NOAA 2 Tropical depressions and tropical storms, while generally less dangerous than hurricanes, still can be deadly. -

A Civic Republican View of Hospital Closures and Community Health Planning Jin Hee Lee New York Lawyers for the Public Interest

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 35 | Number 3 Article 3 2008 A Civic Republican View of Hospital Closures and Community Health Planning Jin Hee Lee New York Lawyers for the Public Interest Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jin Hee Lee, A Civic Republican View of Hospital Closures and Community Health Planning, 35 Fordham Urb. L.J. 561 (2008). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol35/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CIVIC REPUBLICAN VIEW OF HOSPITAL CLOSURES AND COMMUNITY HEALTH PLANNING Jin Hee Lee* I. INTRODUCTION Listening to today's news, it is impossible not to hear someone call for immediate health care reform. The uninsured, rising health care costs, the diabetes epidemic, the financial instability of health care facilities-these are just some of the issues that have contrib- uted to what has become a health crisis of epic proportions. Presi- dential candidates,1 former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer,2 and even New York City Council Speaker Christine Quinn3 have presented various reform proposals to cover the uninsured and un- derinsured, expand primary care, and curb inflated health care costs in an effort to manage this crisis. What is missing from these proposals, however, is a crucial element that health care policy- makers have overlooked for far too long: meaningful community participation in a deliberative process whereby community re- sidents can influence decisions about their local health care resources.