Journal No.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Dorset Rural Area Profile Christchurch and East Dorset East Dorset Rural Area Profile

Core Strategy Area Profile Options for Consideration Consultation 4th October – 24th December 2010 East Dorset Rural Area Prepared by Christchurch Borough Council and East Dorset District Council as part of the Local Development Framework October 2010 Contents 1 Area Overview 2 2 Baseline Data 2 3 Planning Policy Context 3 4 Existing Community Facilities 4 5 Accessibility Mapping 5 6 Community Strategy Issues 5 7 Retail Provision 6 8 Housing 6 9 Employment 13 10 Transport 16 11 Core Strategic Messages 18 East Dorset Rural Area Profile Christchurch and East Dorset East Dorset Rural Area Profile 1 Area Overview 1.1 The rural area of East Dorset is made up of the villages and rural area outside of the main urban settlements of the the District, which form part of the South East Dorset Conurbation. 1.2 The villages can be divided into two types, the smaller villages of Chalbury, Edmondsham, Furzehill, Gaunt’s Common, Gussage All Saints, Gussage St Michael, Hinton Martell, Hinton Parva, Holt, Horton, Long Crichel, Moor Crichel, Pamphill, Shapwick, Wimborne St Giles, Witchampton and Woodlands and the four larger villages of Sturminster Marshall, Cranborne, Alderholt and Sixpenny Handley have a larger range of facilities. 1.3 The southerly villages from Edmondsham southwards to Holt and Pamphill are constrained by the South East Dorset Green Belt while the more northerly and easterly ones from Pentridge southwards to Sturminster Marshall fall within the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. 2 Baseline Data 2.1 The total population in the 2001 census for the smaller villages was 5,613. -

Cranborne Chase 13.Pub

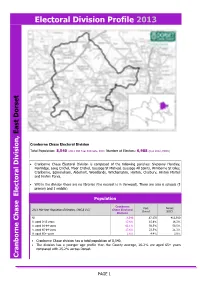

Electoral Division Profile 2013 East Dorset Cranborne Chase Electoral Division Total Population: 8,540 (2011 Mid Year Estimate, DCC) Number of Electors: 6,988 (Dec 2012, EDDC) Cranborne Chase Electoral Division is composed of the following parishes: Sixpenny Handley, Pentridge, Long Crichel, Moor Crichel, Gussage St Micheal, Gussage All Saints, Wimborne St Giles, Cranborne, Edmonsham, Alderholt, Woodlands, Witchampton, Horton, Chalbury, Hinton Martell and Hinton Parva. Within the division there are no libraries (the nearest is in Verwood). There are also 6 schools (5 primary and 1 middle). Population Cranborne East Dorset 2011 Mid-Year Population Estimates, ONS & DCC Chase Electoral Dorset (DCC) Division All 8,540 87,170 412,910 % aged 0-15 years 17.6% 15.6% 16.3% % aged 16-64 years 62.1% 56.5% 58.5% % aged 65-84 years 17.6% 23.5% 21.3% % aged 85+ years 2.6% 4.4% 3.9% Cranborne Chase division has a total population of 8,540. The division has a younger age profile than the County average, 20.2% are aged 65+ years compared with 25.2% across Dorset. Cranborne Chase Electoral Division, PAGE 1 Ethnicity/Country of Birth Cranborne Chase East Dorset Census, 2011 Electoral Dorset (DCC) Division % white British 96.7 96.2 95.5 % Black and minority ethnic groups (BME) 3.3 3.8 4.5 % England 92.3 91.8 91.0 % born rest of UK 3.3 3.3 3.4 % Rep of IRE 0.3 0.4 0.4 % EU (member countries in 2001) 1.3 1.2 1.3 % EU (Accession countries April 2001 to March 2011) 0.3 0.4 0.7 % born elsewhere 2.6 2.9 3.1 The proportion from black and minority ethnic groups is lower than the County average (3.3% compared with 4.5%). -

Word Version

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for East Dorset Report to the Electoral Commission April 2002 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2002 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Boundary Committee for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report Number: 276 2 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? 5 SUMMARY 7 1 INTRODUCTION 13 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 15 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 19 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 21 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 23 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 47 APPENDIX A Final Recommendations for East Dorset: 49 Detailed Mapping A large map illustrating the existing and proposed ward boundaries for Colehill, Ferndown, Verwood and Wimborne Minster is inserted inside the back cover of this report. BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND 3 4 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to the Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No 3692). -

Bulletin of Change to Local Authority Arrangements, Areas and Names in England; 2015

Bulletin of Change to local authority arrangements, areas and names in England; 2015 Part A Changes effected by Order of the Secretary of State 1. Changes effected by Order of the Secretary of State under section 86 (A1), (4) (7), 87 (1), (3) and 105 of the Local Government Act 2000. There are three Orders made by the Secretary of State, which made changes to the scheme of elections. The Borough of Rotherham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 This Order provides a new scheme for the holding of the ordinary elections of councillors of all wards within the borough of Rotherham. It replaces the previous scheme for the ordinary election of councillors by thirds. It also changes the year of election for parish councillors for all parishes within the borough. The City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 This Order provides a new scheme for the holding of the ordinary elections of councillors of all wards in the City of Birmingham. It replaces the previous scheme for the ordinary election of councillors by thirds. It also changes the year of election for parish councillors in the parish of New Frankley within the city. The City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) (Amendment) Order 2015 The City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 (S.I.2015/43) provides a new scheme for the holding of the ordinary elections of councillors of all wards in the City of Birmingham from 2017. It also provides for the parish of New Frankley to have parish council elections in 2017. This Order amends the City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 so that the first elections will take place in 2018. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for East Dorset

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for East Dorset October 2001 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2001 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND? v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 5 3 SUBMISSIONS RECEIVED 9 4 ANALYSIS AND DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 11 5 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 33 APPENDICES A Draft Recommendations for East Dorset: 35 Detailed Mapping B Code of Practice on Written Consultation 39 A large map illustrating the existing and proposed ward boundaries for Colehill, Ferndown, Verwood and Wimborne Minster is inserted inside the back cover of this report. LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND? The Local Government Commission for England is an independent body set up by Parliament. Our task is to review and make recommendations on whether there should be changes to local authorities’ electoral arrangements. Members of the Commission: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) We are required by law to review the electoral arrangements of every principal local authority in England. -

The Chase, the Hart and the Park an Exploration of the Historic Landscapes of the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

The Chase, the Hart and Park The Chase, the Hart and the Park An exploration of the historic landscapes of the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty This publication was prepared following a one-day seminar held by the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in November 2006. The day was open to anyone interested in finding out more about recent work on this remarkable historic landscape. A panel of speakers were invited to follow in some of the best traditions of a BBC ‘Time Team’ style exercise in setting out what it is we know and how we know it - and what it is we don’t know and would like to find out. The papers are published here in the order in which they were given. It is hoped this will be the first of an Occasional Papers Series which will explore various aspects of the history and the natural history in the making of a very distinctive tract of countryside which lies across the borders of four counties, Dorset, Wiltshire, Hampshire and Somerset. The aim of the series is to make current research on this area available to a much wider readership than would normally be possible through strictly academic publication. Each contributor has been invited to append an outline of sources, notes for further reading and to make reference to forthcoming academic publication where applicable. The Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty is a nationally designated landscape covering 981 square kilometres of Dorset, Hampshire, Wiltshire and Somerset. -

Christchurch Borough Council and East Dorset District Council Housing Allocation Policy

1 CHRISTCHURCH BOROUGH COUNCIL AND EAST DORSET DISTRICT COUNCIL JOINT ALLOCATION POLICY. DECEMBER 2013 Amended NOVEMBER 2016 Contents Section 1 Introduction 2 Statutory Background 3 Introduction to the CED Allocation Policy 4 Qualification for the CED Allocation Policy 5 CED Priorities 6 Determining priorities of applicants 7 Administering applications 8 Allocations and Lettings 9 Administration Appendix 1 Allocating Temporary Accommodation Appendix 2 Allocating Extra Care Accommodation Appendix 3 Sensitive Lettings Appendix 4 Owner Occupiers Appendix 5 Summary of bands Appendix 6 Medical and Welfare Assessment Appendix 7 Definitions 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Christchurch Borough Council and East Dorset District Council (known as the Councils in this document), have agreed a common approach for the allocation of social housing across the two local authority areas and have joined a wider Dorset Partnership to operate a choice based lettings scheme called Dorset Home Choice. The scheme is made up of 8 local authority partners operating 3 different allocation policies. This document outlines the allocation policy for the Christchurch and East Dorset Councils (known as CED in this document). Choice based lettings is a system for letting social housing which allows housing applicants more choice by advertising vacancies and inviting applicants to express an interest in being the tenant of any given property. 1.2 The Policy has been developed within the context of national policy particularly the freedoms and flexibilities granted to local authorities -

Agenda Document for Dorset Council

Public Document Pack Cabinet Date: Tuesday, 3 November 2020 Time: 10.00 am Venue: MS Teams Live Event Membership: (Quorum 3) Spencer Flower (Chairman), Peter Wharf (Vice-Chairman), Ray Bryan, Graham Carr- Jones, Tony Ferrari, Laura Miller, Andrew Parry, Gary Suttle, Jill Haynes and David Walsh Cabinet Lead Members (6) (are not members of the Cabinet but are appointed to work along side Portfolio Holders) Cherry Brooks, Piers Brown, Simon Gibson, Nocturin Lacey-Clarke, Byron Quayle and Jane Somper Chief Executive: Matt Prosser, South Walks House, South Walks Road, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1UZ (Sat Nav DT1 1EE) For easy access to the Council agendas and minutes download the free public app Mod.gov for use on your iPad, Android and Windows tablet. Once downloaded select Dorset Council. For more information about this agenda please contact Kate Critchel 01305 252234 - [email protected] Due to the current coronavirus pandemic the Council has reviewed its approach to holding committee meetings. Members of the public are welcome to attend this meeting and listen to the debate either online by using the following link: Link to meeting via Teams Live Event Members of the public wishing to view the meeting from an iphone, ipad or android phone will need to download the free Microsoft Team App to sign in as a Guest, it is advised to do this at least 30 minutes prior to the start of the meeting.” Please note that public speaking has been suspended. However Public Participation will continue by written submission only. Please see detail set out below. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 384 LOCAL GOVERHKHJT BOTJHDAHY COMMISSION FOH EHGLAED CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KGB DEPUT7 CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin MJSfiBERS Lady Bo?:den Mr J T Brockbank Mr R H Thornton C3E DL Mr B P Harrison Professor G B Cherry PH To the Rt Hon William Whitelaw, CH MC, MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE DISTRICT OF WIMBORNE IN THE COUNTY OF DORSET 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the district of Wimborne, in accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that district. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in Section 60(1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 31 December 197^ that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to Wimborne District Council, copies of which were circulated to Dorset County Council, town councils, parish councils and parish meetings in the district, the Member of Parliament for the constituency concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of the local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies. 3. Wimborne District Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representation for our consideration. -

East Dorset Local Plan Options East Dorset District Council Contents

Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Picture of East Dorset 8 3 Strategic Policy 19 3.1 Challenges, Vision & Strategic Objectives 19 3.2 The Key Strategy 25 4 Core Policies & Development Management 53 4.1 Environment 53 4.2 Green Belt 74 4.3 Housing 79 4.4 Heritage & Conservation 89 4.5 Landscape, Design & Open Spaces 91 4.6 Economic Growth 99 4.7 Bournemouth Airport 110 5 Site Allocations and Area Based Policies 116 5.1 Wimborne, Colehill & Corfe Mullen 116 5.1.1 Introduction 116 5.1.2 Housing 116 5.1.3 Open Space 141 5.1.4 Town, District & Local Centres 144 5.2 Ferndown, West Parley and Longham 150 5.2.1 Introduction 150 5.2.2 Housing 150 5.2.3 Open Space 170 5.2.4 Town, District & Local Centres 170 5.2.5 Employment 180 5.3 Verwood, St Leonards, St Ives & West Moors 182 5.3.1 Introduction 182 5.3.2 Housing 183 5.3.3 Open Space 201 5.3.4 Town, District & Local Centres 202 5.3.5 Community Facilities & Services 208 East Dorset Local Plan Options East Dorset District Council Contents 5.4 Rural settlements in East Dorset 210 5.4.1 Introduction 210 5.4.2 Alderholt 211 5.4.3 Cranborne 218 5.4.4 Edmondsham 224 5.4.5 Furzehill 229 5.4.6 Gaunts Common 232 5.4.7 Gussage All Saints 234 5.4.8 Gussage St Michael 235 5.4.9 Hinton Martell 235 5.4.10 Holt 240 5.4.11 Horton 242 5.4.12 Longham 243 5.4.13 Shapwick 245 5.4.14 Sixpenny Handley 246 5.4.15 Sturminster Marshall 252 5.4.16 Three Legged Cross 261 5.4.17 Wimborne St Giles 263 5.4.18 Woodlands / Whitmore 268 Appendices A Affordable Housing Definitions 272 B Guidelines for the Establishment of Suitable Alternative Natural Greenspace (SANGs) 276 C Glossary 284 East Dorset District Council East Dorset Local Plan Options Introduction 1 East Dorset Local Plan Options East Dorset District Council 1 1 Introduction 1 Introduction What is the Local Plan (Review)? 1.0.1 The East Dorset Local Plan (Review) is the document which sets out the planning strategy for East Dorset District over the next 15 years to 2033. -

The History of Wimborne Workhouse by Janet K L Seal

1 The History of Wimborne Workhouse By Janet K L Seal The terms ‘workhouse’, ‘poor-house’ and ‘hospital’ seem to be inter- changeable in medieval records. All catered for the needs of the poor, the sick and the homeless with varying degrees of kindness and efficiency. From catering for two dozen to two hundred souls, the housing of the destitute has been well recorded in the parish of Wimborne and later in an area encompassing many local villages. The gradual transfer of the responsibility for needy residents from the church to a secular committee of parish leaders can be traced by an addition to the rates for that particular purpose. 1483 Entry in churchwardens records ‘ad finam occid ‘Turris de Wymborn’ referring to the workhouse called St Mary’s house. 1479 St Mary's House mentioned by Hutchins as being a poor house. 20d rent paid by the Minster churchwardens to Lord of Hampreston. There may have been up to two dozen people there because in 1495 two dozen wooden dishes were purchased. John Cole and John Scote made doors with locks as well as an ‘entirclos1 in le workhouse.’ Under the entry for year 1483 St Mary's House is mentioned as being at the end of the West Tower of the Minster. From the known plans of the Minster there is no evidence that this house was built of stone. It might therefore have looked like the adjacent sketch, the screen dividing male and female wards in a wooden annexe. Sketch by author 1524 Wimborne church wardens refer to ‘a tenement late called Saynte Marye House’, an ancient hospital or workhouse for the relief and employment of poor people. -

SIF Implementation Specification (UK)

table of contents Schools Interoperability Framework™ Implementation Specification (United Kingdom) 1.1 June 19, 2008 This version: http://specification.sifinfo.org/Implementation/UK/1.1/ Previous version: http://specification.sifinfo.org/Implementation/UK/1.0/ Latest version: http://specification.sifinfo.org/Implementation/UK/ 1 of 1189 Schemas SIF_Message (single file, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) SIF_Message (single file, annotated) (ZIP archive) SIF_Message (includes, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) SIF_Message (includes, annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (single file, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (single file, annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (includes, non-annotated) (ZIP archive) DataModel (includes, annotated) (ZIP archive) Note: SIF_Message schemas define every data object element as optional per SIF's Publish/Subscribe and SIF Request/Response Models; DataModel schemas maintain the cardinality of all data object elements. Please refer to the errata for this document, which may include some normative corrections. This document is also available in these non-normative formats: ZIP archive, PDF (for printing as a single file), Excel spreadsheet. Copyright ©2008 Schools Interoperability Framework (SIF™) Association. All Rights Reserved. 2 of 1189 3 of 1189 1 Preamble 1.1 Abstract 1.1.1 What is SIF? The Schools Interoperability Framework (SIF) is not a product, but a technical blueprint for enabling diverse applications to interact and share data related to entities in the pK-12 instructional and administrative environment.