The History of Wimborne Workhouse by Janet K L Seal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Dorset Rural Area Profile Christchurch and East Dorset East Dorset Rural Area Profile

Core Strategy Area Profile Options for Consideration Consultation 4th October – 24th December 2010 East Dorset Rural Area Prepared by Christchurch Borough Council and East Dorset District Council as part of the Local Development Framework October 2010 Contents 1 Area Overview 2 2 Baseline Data 2 3 Planning Policy Context 3 4 Existing Community Facilities 4 5 Accessibility Mapping 5 6 Community Strategy Issues 5 7 Retail Provision 6 8 Housing 6 9 Employment 13 10 Transport 16 11 Core Strategic Messages 18 East Dorset Rural Area Profile Christchurch and East Dorset East Dorset Rural Area Profile 1 Area Overview 1.1 The rural area of East Dorset is made up of the villages and rural area outside of the main urban settlements of the the District, which form part of the South East Dorset Conurbation. 1.2 The villages can be divided into two types, the smaller villages of Chalbury, Edmondsham, Furzehill, Gaunt’s Common, Gussage All Saints, Gussage St Michael, Hinton Martell, Hinton Parva, Holt, Horton, Long Crichel, Moor Crichel, Pamphill, Shapwick, Wimborne St Giles, Witchampton and Woodlands and the four larger villages of Sturminster Marshall, Cranborne, Alderholt and Sixpenny Handley have a larger range of facilities. 1.3 The southerly villages from Edmondsham southwards to Holt and Pamphill are constrained by the South East Dorset Green Belt while the more northerly and easterly ones from Pentridge southwards to Sturminster Marshall fall within the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. 2 Baseline Data 2.1 The total population in the 2001 census for the smaller villages was 5,613. -

Cranborne Chase 13.Pub

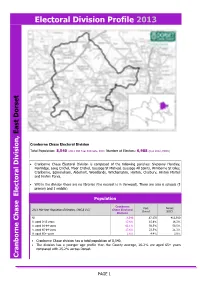

Electoral Division Profile 2013 East Dorset Cranborne Chase Electoral Division Total Population: 8,540 (2011 Mid Year Estimate, DCC) Number of Electors: 6,988 (Dec 2012, EDDC) Cranborne Chase Electoral Division is composed of the following parishes: Sixpenny Handley, Pentridge, Long Crichel, Moor Crichel, Gussage St Micheal, Gussage All Saints, Wimborne St Giles, Cranborne, Edmonsham, Alderholt, Woodlands, Witchampton, Horton, Chalbury, Hinton Martell and Hinton Parva. Within the division there are no libraries (the nearest is in Verwood). There are also 6 schools (5 primary and 1 middle). Population Cranborne East Dorset 2011 Mid-Year Population Estimates, ONS & DCC Chase Electoral Dorset (DCC) Division All 8,540 87,170 412,910 % aged 0-15 years 17.6% 15.6% 16.3% % aged 16-64 years 62.1% 56.5% 58.5% % aged 65-84 years 17.6% 23.5% 21.3% % aged 85+ years 2.6% 4.4% 3.9% Cranborne Chase division has a total population of 8,540. The division has a younger age profile than the County average, 20.2% are aged 65+ years compared with 25.2% across Dorset. Cranborne Chase Electoral Division, PAGE 1 Ethnicity/Country of Birth Cranborne Chase East Dorset Census, 2011 Electoral Dorset (DCC) Division % white British 96.7 96.2 95.5 % Black and minority ethnic groups (BME) 3.3 3.8 4.5 % England 92.3 91.8 91.0 % born rest of UK 3.3 3.3 3.4 % Rep of IRE 0.3 0.4 0.4 % EU (member countries in 2001) 1.3 1.2 1.3 % EU (Accession countries April 2001 to March 2011) 0.3 0.4 0.7 % born elsewhere 2.6 2.9 3.1 The proportion from black and minority ethnic groups is lower than the County average (3.3% compared with 4.5%). -

Bulletin of Change to Local Authority Arrangements, Areas and Names in England; 2015

Bulletin of Change to local authority arrangements, areas and names in England; 2015 Part A Changes effected by Order of the Secretary of State 1. Changes effected by Order of the Secretary of State under section 86 (A1), (4) (7), 87 (1), (3) and 105 of the Local Government Act 2000. There are three Orders made by the Secretary of State, which made changes to the scheme of elections. The Borough of Rotherham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 This Order provides a new scheme for the holding of the ordinary elections of councillors of all wards within the borough of Rotherham. It replaces the previous scheme for the ordinary election of councillors by thirds. It also changes the year of election for parish councillors for all parishes within the borough. The City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 This Order provides a new scheme for the holding of the ordinary elections of councillors of all wards in the City of Birmingham. It replaces the previous scheme for the ordinary election of councillors by thirds. It also changes the year of election for parish councillors in the parish of New Frankley within the city. The City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) (Amendment) Order 2015 The City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 (S.I.2015/43) provides a new scheme for the holding of the ordinary elections of councillors of all wards in the City of Birmingham from 2017. It also provides for the parish of New Frankley to have parish council elections in 2017. This Order amends the City of Birmingham (Scheme of Elections) Order 2015 so that the first elections will take place in 2018. -

Agenda Document for Dorset Council

Public Document Pack Cabinet Date: Tuesday, 3 November 2020 Time: 10.00 am Venue: MS Teams Live Event Membership: (Quorum 3) Spencer Flower (Chairman), Peter Wharf (Vice-Chairman), Ray Bryan, Graham Carr- Jones, Tony Ferrari, Laura Miller, Andrew Parry, Gary Suttle, Jill Haynes and David Walsh Cabinet Lead Members (6) (are not members of the Cabinet but are appointed to work along side Portfolio Holders) Cherry Brooks, Piers Brown, Simon Gibson, Nocturin Lacey-Clarke, Byron Quayle and Jane Somper Chief Executive: Matt Prosser, South Walks House, South Walks Road, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1UZ (Sat Nav DT1 1EE) For easy access to the Council agendas and minutes download the free public app Mod.gov for use on your iPad, Android and Windows tablet. Once downloaded select Dorset Council. For more information about this agenda please contact Kate Critchel 01305 252234 - [email protected] Due to the current coronavirus pandemic the Council has reviewed its approach to holding committee meetings. Members of the public are welcome to attend this meeting and listen to the debate either online by using the following link: Link to meeting via Teams Live Event Members of the public wishing to view the meeting from an iphone, ipad or android phone will need to download the free Microsoft Team App to sign in as a Guest, it is advised to do this at least 30 minutes prior to the start of the meeting.” Please note that public speaking has been suspended. However Public Participation will continue by written submission only. Please see detail set out below. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 384 LOCAL GOVERHKHJT BOTJHDAHY COMMISSION FOH EHGLAED CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KGB DEPUT7 CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin MJSfiBERS Lady Bo?:den Mr J T Brockbank Mr R H Thornton C3E DL Mr B P Harrison Professor G B Cherry PH To the Rt Hon William Whitelaw, CH MC, MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE DISTRICT OF WIMBORNE IN THE COUNTY OF DORSET 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the district of Wimborne, in accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that district. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in Section 60(1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 31 December 197^ that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to Wimborne District Council, copies of which were circulated to Dorset County Council, town councils, parish councils and parish meetings in the district, the Member of Parliament for the constituency concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of the local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies. 3. Wimborne District Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representation for our consideration. -

Journal No.2

T » ?1 ! 1 T II INDEX Foreword 1 * Rescue Excavation Blandford By-Pass, 1983 2 Henge Monuments 5 Excavation of Ring Ditch at Wyke Down 6 Book Reviews 9 Rempstone - A Study in Neglect 10 Book Review 15 Extracts from Experimental Shale Working Projects 16 Archaeological Excavations on the site of the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Wimbome Minster 18 Road Fever 23 Animal Safari 26 Tarrant Abbey 28 The Seventeenth Century Token Coinage of East Dorset 31 The Red House Museum 35 COMMITTEE MEMBERS 1984/85 Chairman: John W Day General Secretary: Dennis Bicheno Vice Chairman: Haydn Everall Treasurer: Les Baker Membership Secretary: Della Day Special Adviser: Martin Green Social Secretary: Cherry Trent Members: Janet Bicheno; Sylvia Church; Phil Coles; Teresa Hall; Ann Sims; Bob Vincent We thank Len Norris and Brian Tiller for their work in the past year* FOREWORD We have pleasure in presenting our second Journal, which we hope you will read and enjoy* The first year of E.D.A.S. has been one full of interest and varied activity, and two excavations have been particularly exciting. The discovery of a Henge Monument at Wyke Down, Gussage St. Michael was most unexpected and is the first in Wessex* Martin Green now wonders how many of the ring ditch crop and soil marks which he has photographed and not ploughed-out barrows, as hitherto assumed, but more henges. On the Blandford Bypass we excavated part of a Bronze Age village, which made us realise just how much more there is to find. The post-holes of the huts and their porches were clearly visible, despite the passage of earth-moving machinery.