On Religious Toleration: Prudence and Charity in Augustine, Aquinas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Bickel's Philosophy of Prudence

The Yale Law Journal Volume 94, Number 7, June 1985 Alexander Bickel's Philosophy of Prudence Anthony T. Kronmant INTRODUCTION Six years after Alexander Bickel's death, John Hart Ely described his former teacher and colleague as "probably the most creative constitutional theorist of the past twenty years."" Many today would concur in Ely's judgment.' Indeed, among his academic peers, Bickel is widely -regarded with a measure of respect that borders on reverence. There is, however, something puzzling about Bickel's reputation, for despite the high regard in which his work is held, Bickel has few contemporary followers.' There is, today, no Bickelian school of constitutional theory, no group of scholars working to elaborate Bickel's main ideas or even to defend them, no con- tinuing and connected body of legal writing in the intellectual tradition to which Bickel claimed allegiance. In fact, just the opposite is true. In the decade since his death, constitutional theory has turned away from the ideas that Bickel championed, moving in directions he would, I believe, f Professor of Law, Yale Law School. 1. J. ELY, DEMOCRACY AND DISTRUST 71 (1980). 2. See B. SCHMIDT, HISTORY OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES: THE JUDICI- ARY AND RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT 1910-21 (pt. 2) 722 (1984) (describing Bickel as "the most brilliant and influential constitutional scholar of the generation that came of age during the era of the Warren Court"); Ackerman, The Storrs Lectures: Discovering the Constitution, 93 YALE L.J. 1013, 1014 (Bickel "revered as spokesman-in-chief for a school of thought that emphasizes the importance of judicial restraint"). -

Quafter Concluded from Page 18

Quafter Concluded from page 18. Previous to the days of railways, when roads were bad and communication difficult and expensive, Friends did not often go far from home. Heads of families, sometimes accom panied by their sons and daughters, would occasionally go to the Quarterly Meetings, but we can see by the intermarriages of families that acquaintanceship and society were generally limited to those who resided in the neighbourhood. Thus, in a county, the centre of a Monthly Meeting, we find, say, half a dozen families whose members were continually intermarrying. In the County Wexford, for instance, situated as it is in a corner of the island, there were the families of Davis, Woodcock, Sparrow, Martin, Poole, Sandwith, Goff, and Chamberlin, who married and inter married again and again. Cork people married Cork people, and so it was in Limerick and in Waterford, to a degree which nowadays we do not realise. Marriages between Ulster and Munster were, in the eighteenth century, very uncommon. Dublin, naturally, was a kind of meeting- point, and its importance as the capital, and being the seat of the largest Monthly Meeting, led to many marriages there of couples of whom one at least resided in the country. The old rule of not allowing second cousins to be passed for marriage of course very much limited choice. So many in that relationship have been united since the rule was relaxed that, we may take it, if such alteration had not taken place, a dead lock and a break up would have occurred. While the change, and, perhaps, that of allowing first and second cousins4 also to many, can hardly be regretted, it is to be hoped that the latitude sanctioned by London Yearly Meeting as regards first cousins may continue to be forbidden in this country.5 All are agreed that as regards consanguinity 4 What we in this country understand by this term, is the relationship between a person and the child of his first cousin. -

An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion Michael J

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85369-9 - An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion Michael J. Murray and Michael C. Rea Index More information Index Adams, Robert M., 239, 240–2, 243, 245, Christology 248, 249 three-part, 84 afterlife, see immortality two-part, 83–4 Alston, William, 108, 109 see also Incarnation Anselm, of Canterbury St., 8, 12–13 Commissurotomy, see Trinity, and and perfect-being theology, 8 commissurotomy Ontological Argument, 124–35 compatibilism, 54, 61 Apollinarianism, 81 Constitution Trinitarianism, see Trinity, Aquinas, Thomas St., 30, 61, 100, statue–lump analogy 238, 263 Cosmological Argument, 135–46 Arianism, 81 Kalam version, 143–6 Aristotle, 73 counterfactual, 53 aseity, see self-existence of freedom, 59, 60–1 Assumption, 84 power, 53–4 atemporality, 40; see also eternity see also Molinism; Ockhamism Athanasian Creed, 66 Craig, William Lane, 143, 145 atheism creation, 22–3, 26–33 arguments for, see God, arguments Cryptomnesia, 277 against the existence of evolutionary argument against, see Davis, Stephen, 76 Evolution Dawkins, Richard, 97, 221 Augustine, St., 61, 70 Dembski, William, 215–16 Descartes, Rene´, 17, 125–6, 263 basic belief, 108 Design Arguments, 146–55 Basil, St., 69 argument from analogy, 147–8 Bayle, Pierre, 252 inference to the best explanation Behe, Michael, 216–20 argument, 148–9 Bergmann, Michael, 110 fine-tuning argument, Boethius, 40, 41 150–5 Brower, Jeffrey, 66, 67 determinism, 54 divine command ethics, see ethics; Calvin, John, 61 divine commands Calvinism, see Providence Docetism, 81 Chalcedonian Creed, 80 Draper, Paul, 178–80 287 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85369-9 - An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion Michael J. -

Nominalism, Romanticism, Negative Dialectics by Megan A. O'connor A

Nominalism, Romanticism, Negative Dialectics By Megan A. O’Connor A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Steven Goldsmith, Chair Professor Kevis Goodman Professor Celeste Langan Professor Martin Jay Spring 2019 Nominalism, Romanticism, Negative Dialectics © 2019 by Megan A. O’Connor Abstract Nominalism, Romanticism, Negative Dialectics by Megan A. O’Connor Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Steven Goldsmith, Chair This dissertation recovers a neglected dialectical tradition within British empiricism and its Romantic afterlife. Beginning with John Locke, I demonstrate how a dialectical tradition developed as a self-critical response to the political, philosophical, and aesthetic problem of nominalism, which holds that universals do not exist and that everything is particular. As contemporaries like Dugald Stewart and S.T. Coleridge observed, British empiricists had revived the medieval nominalist-realist debates and sided with the nominalists. I show that nominalism – what Karl Marx called the “first form” of materialism – was taken up and critiqued by Romantic poets as an impediment to the task of representing abstract social and historical forces. Romantic poets as distinct as Coleridge, William Blake, and Charlotte Smith suggest that, in questioning the validity of social abstractions, the nominalist bent of empiricism tended to disable critical interrogations of larger social structures that otherwise remain inaccessible to the senses. In diagnosing the abstracting force of historical conditions like the commodification of the literary marketplace, however, the texts I examine also respond by affirming particularity. -

Philosophy of Religion (HSA020N247H) | University of Roehampton

09/25/21 Philosophy of Religion (HSA020N247H) | University of Roehampton Philosophy of Religion (HSA020N247H) View Online (Module Validation) Philosophy of Religion How are we to approach the philosophy of religion? Is it more than the philosophy of God? and what, if anything, does it have to do with the various practical and moral issues which occupy us as human beings? We shall approach the subject in a manner which acknowledges the significance of these practical and methodological issues, and will consider questions such as the following. What is the relation between science and religion? Does it make sense to say that there is purpose in the natural world? How are we to understand the purpose of our human lives? What is the relation between spirituality and religion? Is God necessary for morality? What is religious experience? Is there anything problematic in the idea that we need to be saved? 121 items Key Texts (1 items) Philosophy of Religion: Towards a More Humane Approach - John Cottingham, 2014 Book | Essential Reading Topic 1: What is philosophy of religion? (7 items) See accompanying handouts for each lecture New models of religious understanding - 2018 Book | Essential Reading | The Introduction is helpful in this context. Philosophy of Religion: Towards a More Humane Approach - John Cottingham, 2014 Book | Essential Reading | ch 1, ‘Method’ Why Philosophy Matters for the Study of Religion--And Vice Versa - Thomas A. Lewis, 2017 Book | Essential Reading | Introduction and ch 1. What is philosophy of religion? - Charles Taliaferro, 2019 Book | Essential Reading | ch 1. 1/11 09/25/21 Philosophy of Religion (HSA020N247H) | University of Roehampton Prolegomena to a philosophy of religion - J. -

St Mary's Catholic Church Chorley

CHORLEY HOSPITAL: Please contact St Joseph's Chorley (262713) if any member of your family is admitted into Chorley Hospital and needs a visit. In an emergency ask St Mary’s Catholic Church Chorley the staff to bleep the on-call priest. For the chaplaincy service at Royal Preston Hospital please ring 01772 522435, or in emergency please ask the staff to contact the on-call priest from St Clare’s Parish or elsewhere. FIFTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME th ST ANNE’S GUILD: next bingo is on 12 February at 19.45 in the Parish Centre. th 10 February 2019 ADVANCE NOTICE: Ash Wednesday: 6th March, Chrism Mass at Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool: Wednesday 17th April. Triduum: Holy Thursday 18th April. Jesus was standing one day by Good Friday 19th April. Easter Saturday: 20th April. Easter Sunday 21st April. Divine the Lake of Gennesaret, with the Mercy Sunday 28th April. There will be a coach travelling to the Chrism Mass, as crowd pressing round him usual. Details will be announced at the beginning of April. listening to the word of God, Please note: This year there will be only ONE Reconciliation Service for the when he caught sight of two Deanery. Please pass the word around. Details will follow. boats close to the bank. The fishermen had gone out of them O Dear Jesus, and were washing their nets. He I humbly implore You to grant Your special graces to our family. got into one of the boats – it was May our home be the shrine of peace, purity, love, labour and faith. -

Emergentism As an Option in the Philosophy of Religion: Between Materialist Atheism and Pantheism

SURI 7 (2) 2019: 1-22 Emergentism as an Option in the Philosophy of Religion: Between Materialist Atheism and Pantheism James Franklin University of New South Wales Abstract: Among worldviews, in addition to the options of materialist atheism, pantheism and personal theism, there exists a fourth, “local emergentism”. It holds that there are no gods, nor does the universe overall have divine aspects or any purpose. But locally, in our region of space and time, the properties of matter have given rise to entities which are completely different from matter in kind and to a degree god-like: consciousnesses with rational powers and intrinsic worth. The emergentist option is compared with the standard alternatives and the arguments for and against it are laid out. It is argued that, among options in the philosophy of religion, it involves the minimal reworking of the manifest image of common sense. Hence it deserves a place at the table in arguments as to the overall nature of the universe. Keywords: Emergence; pantheism; personal theism; naturalism; consciousness 1. INTRODUCTION The main options among world views are normally classifiable as either materialist atheism, pantheism (widely understood) or personal theism. According to materialist atheism, there exists nothing except the material universe as we ordinarily conceive it, and its properties are fully described by science (present or future). According to personal theism, there exists a separate entity (or entities) of a much higher form than those found in the 2019 Philosophical Association of the Philippines 2 Emergentism as an Option in the Philosophy of Religion material universe, a god or gods. -

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

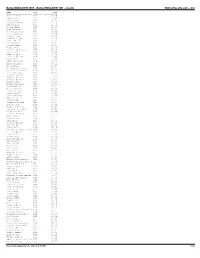

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

Justifying Religious Freedom: the Western Tradition

Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition E. Gregory Wallace* Table of Contents I. THESIS: REDISCOVERING THE RELIGIOUS JUSTIFICATIONS FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.......................................................... 488 II. THE ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN EARLY CHRISTIAN THOUGHT ................................................................................... 495 A. Early Christian Views on Religious Toleration and Freedom.............................................................................. 495 1. Early Christian Teaching on Church and State............. 496 2. Persecution in the Early Roman Empire....................... 499 3. Tertullian’s Call for Religious Freedom ....................... 502 B. Christianity and Religious Freedom in the Constantinian Empire ................................................................................ 504 C. The Rise of Intolerance in Christendom ............................. 510 1. The Beginnings of Christian Intolerance ...................... 510 2. The Causes of Christian Intolerance ............................. 512 D. Opposition to State Persecution in Early Christendom...... 516 E. Augustine’s Theory of Persecution..................................... 518 F. Church-State Boundaries in Early Christendom................ 526 G. Emerging Principles of Religious Freedom........................ 528 III. THE PRESERVATION OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION EUROPE...................................................... 530 A. Persecution and Opposition in the Medieval -

Plato: the Virtues of Philosophical Leader

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojsp.html Open Journal for Studies in Philosophy, 2018, 2(1), 1-8. ISSN (Online) 2560-5380 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsp.0201.01001k _________________________________________________________________________ Plato: The Virtues of Philosophical Leader Ioanna-Soultana Kotsori University of Peloponnese, Kalamata Faculty of Humanities and Cultural Studies Received 22 February 2018 ▪ Revised 25 May 2018 ▪ Accepted 11 June 2018 Abstract The entrance into the reflection of the present work is made with the philosophical necessity of the leader in society, the leader with the particular characteristics of love and wisdom, from which his personality must possess so that by art he can compose opposing situations and move society towards the unity and bliss of citizens. A gentle royal nature (genotype), which blends with the excellent treatment of morality, body and spirit, will create the ideal model leader (phenotype). Thus, noble nature and royal law will give the state the excellent leader. Even if the forms and the conditions that determine them change, the one that remains stable and permanent is the Platonic ethos in art and the science of politics and administration in general. The salvation from corruption is from childhood the cultivation of man by treating at the same time the moral of the soul, the beauty of the body and the wisdom of the spirit. Keywords: philosophical king, education, wisdom, ethos, leader, excellent state, virtues. 1. Introduction Plato’s works demonstrate that he cared for man and society, trying to radically improve morality. Plato’s character was not such as to pursue leadership positions to meet his personal needs and shows his responsibility to the leader’s heavy role. -

The Cardinal and Theological Virtues

LESSON 5 The Cardinal and Theological Virtues BACKGROUND READING We don’t often reflect on the staying power Human or Cardinal Virtues that habits have in our lives. Ancient wisdom The four cardinal virtues are human virtues that tells us that habits become nature. We are what govern our moral choices. They are acquired repeatedly do. If we do something over and over by human effort and perfected by grace. The again, eventually we will do that thing without four cardinal virtues are: prudence, justice, thinking. For example, if a person has chewed temperance, and fortitude. The word cardinal her nails all of her life, then chewing nails comes from a Latin word that means “hinge” becomes an unconscious habit that is difficult or “pivot.” All the other virtues are connected to break. Perhaps harder to cultivate are the to, or hinge upon, the cardinal virtues. Without good habits in our lives. If we regularly take time the cardinal virtues, we are not able to live the to exercise, to say no to extra desserts, to get other virtues. up early to pray, to think affirming thoughts of Prudence “disposes practical reason to others, these too can become habits. discern our true good in every circumstance The Catechism of the Catholic Church and to choose the right means of achieving it” defines virtue as “an habitual and firm (CCC 1806). We must recall that our true good disposition to do the good. It allows the person is always that which will lead us to Heaven, so not only to perform good acts, but also to that perhaps another way of saying this is that give the best of himself.