Court: Decision Date: File Reference: ECLI: Document Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Deir Ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested During SDF's “Deterrence

Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign www.stj-sy.org Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign This joint report is brought by Justice For Life (JFL) and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) Page | 2 Deir ez-Zor: Dozens Arbitrarily Arrested during SDF’s “Deterrence of Terrorism” Campaign www.stj-sy.org 1. Executive Summary The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) embarked on numerous raids and arrested dozens of people in its control areas in Deir ez-Zor province, located east of the Euphrates River, during the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign it first launched on 4 June 2020 against the cells of the Islamic State (IS), aka Daesh. The reported raids and arrests were spearheaded by the security services of the Autonomous Administration and the SDF, particularly by the Anti-Terror Forces, known as the HAT.1 Some of these raids were covered by helicopters of the US-led coalition, eyewitnesses claimed. In the wake of the campaign’s first stage, the SDF announced that it arrested and detained 110 persons on the charge of belonging to IS, in a statement made on 10 June 2020,2 adding that it also swept large-scale areas in the suburbs of Deir ez-Zor and al-Hasakah provinces. It also arrested and detained other 31 persons during the campaign’s second stage, according to the corresponding statement made on 21 July 2020 that reported the outcomes of the 4- day operation in rural Deir ez-Zor.3 “At the end of the [campaign’s] second stage, the participant forces managed to achieve the planned goals,” the SDF said, pointing out that it arrested 31 terrorists and suspects, one of whom it described as a high-ranking IS commander. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

Information and Liaison Bulletin N° 409

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 409 APRIL 2019 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Misen en page et maquette : Ṣerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 409 April 2019 • ROJAVA: UNCERTAINTIES AFTER THE FALL OF ISIS • FRANCE: THE FRENCH PRESIDENT RECEIVES A SDF DELEGATION, PROVOKING ANKARA’S ANGER • TURKEY: AKP LOSES ANKARA AND ISTAN- BUL, ORGANISES “ELECTORAL HOLD-UP” AGAINST EIGHT HDP WINNERS IN THE EAST • IRAQ: STILL NO REGIONAL GOVERNMENT IN KURDISTAN, VOTERS GET IMPATIENT... • IRAN: BI-NATIONAL OR FOREIGN ENVIRONMENTALISTS ARRESTED IN KURDISTAN LITERALLY TAKEN HOSTAGES BY THE REGIME ROJAVA: UNCERTAINTIES AFTER THE FALL OF ISIS While the takeover by in an artillery fire exchange with Encûmena Niştimanî ya Kurdî li the Syrian Democratic the YPG. In addition, tension in Sûriyê), arrested on 31 March... Forces (SDF) of ISIS's the occupied area also increased last reduction in eastern following a new wave of abuses Kurdish clandestine groups con- W Syria does not mean the by jihadist militias holding the tinued their operations against the end of the jihadist organisation, it area, including kidnappings for occupiers. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

The Arid Soils of the Balikh Basin (Syria)

THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYRIA) M.A. MULDERS ERRATA THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYRIA). M.A. MULDERS, 1969 page 21, line 2 from bottom: read: 1, 4 instead of: 14 page 81, line 1 from top: read: x instead of: x % K page 103t Fig» 19: read: phytoliths instead of: pytoliths page 121, profile 51, 40-100 cm: read: clay instead of: silty clay page 125, profile 26, 40-115 cm: read: silt loam instead of: clay loam page 127, profile 38, 105-150 cm: read: clay instead of: silty loam page 127, profile 42, 14-40 cm: read: silty clay loam instead of: silt loam page 127, profile 42, 4O-6O cm: read: silt loam instead of: clay loam page 138, 16IV, texture: read: 81,5# sand, 14,4% silt instead of: 14,42! sand, 81.3% silt page 163, add: A and P values (quantimet), magnification of thin sections 105x THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYEIA). M.A. MULDERS, 19Ô9 page 18, Table 2: read: mm instead of: min page 80, Fig. 16: read: kaolinite instead of: kaolite page 84, Table 21 : read: Kaolinite instead of: Kaolonite page 99, line 17 from top: read: at instead of: a page 106, line 20 from bottom: read: moist instead of: most page 109t line 8 from bottom: read: recognizable instead of: recognisable page 115» Fig. 20, legend: oblique lines : topsoil, 0 - 30 cm horizontal lines : deeper subsoil, 60 - 100 cm page 159» line 6 from top: read: are instead of: is 5Y THE ARID SOILS OF THE BAUKH BASIN (SYRIA) 37? THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYRIA) PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE WISKUNDE EN NATUURWETENSCHAPPEN AAN DE RIJKS- UNIVERSITEIT TE UTRECHT, OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS, PROF.DR. -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

UNHCR's Operational Update: January-March 2019, English

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Syria January -March 2019 As of end of March, UNHCR In February, UNHCR participated in Since December a major emergency concluded its winterization the largest ever humanitarian in North East Syria led to thousands of programme with the distribution convoy providing life-saving people fleeing Hajin to Al-Hol camp. of 1,553,188 winterized humanitarian assistance to some UNHCR is providing core relief items to 1,163,494 individuals/ 40,000 displaced people at the items, shelter and protection 241,870 families in 13 governorates in Rukban ‘makeshift’ settlement in support for the current population Syria. south-eastern Syria, on the border which exceeds 73,000 individuals. with Jordan. HUMANITARIAN SNAPSHOT 11.7 million FUNDING (AS OF 16 APRIL 2019) people in need of humanitarian assistance USD 624.4 million requested for the Syria Operation 13.2 million Funded 14% people in need of protection interventions 87.4 million 11.3 million people in need of health assistance 4.7 million people in need of shelter Unfunded 86% 4.4 million 537 million people in need of core relief items POPULATION OF CONCERN Internally Displaced Persons Internally displaced persons 6.2 million Returnees Syrian displaced returnees 2018 1.4 million* Syrian refugee returnees 2018 56,047** Syrian refugee returnees 2019 21,575*** Refugees and Asylum seekers Current population 32,289**** Total urban refugees 17,832 Total asylum seekers 14,457 Camp population 30,529***** High Commissioner meets with families in Souran in Rural * OCHA, December 2018 Hama that have returned to their homes and received shelter ** UNHCR, December 2018 *** UNHCR, March 2019 assistance from UNHCR. -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

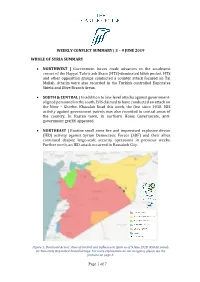

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Volume 22 Issue 2 The Journal of Conventional Weapons Article 4 Destruction Issue 22.2 August 2018 Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria Médecins Sans Frontières MSF Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal Part of the Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frontières, Médecins Sans (2018) "Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria," Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol22/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction by an authorized editor of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frontières: Recovery of Survivors of IEDs and ERW in Northeast Syria Shattered Lives and Bodies: Recovery of Survivors of Improvised Explosive Devices and Explosive Remnants of War in Northeast Syria by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) n northeast Syria, fighting, airstrikes, and artillery shell- children were playing when one of them took an object from ing have led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands the ground and threw it. They did not know it was a mine. It Iof civilians from the cities of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa, as exploded immediately. -

Middle East, North Africa

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA Views from the Frontline: ISIS Still Poses a Danger OE Watch Commentary: Despite losing its territorial control, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) still poses a threat. The accompanying articles from Kurdish sources based in Iraq and Syria shed light on ISIS’s resurgence and capabilities in the region. Many of the group’s fighters and sympathizers had dispersed across Iraq and Syria or gone underground before it received the final blow by opposing forces. Now, it appears that those fighters are resorting to insurgency, rather than striving to control territory, as evidenced by recent attacks in Iraq and Syria. The first article provides the views of Peshmerga commander Wasta Rasul on the situation of ISIS in Iraq. Peshmerga are the military forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq and have been instrumental in fighting ISIS in Iraq. As the commander states, “ISIS has not really been uprooted. The group has only lost the territory it ruled. It has completely regrouped and is stronger than before.” The SDF firing on an ISIS camp, 4 March 2019. article points out that ISIS sleeper cells “continue to launch insurgent Source: VOA via Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SDF_MG_in_Baghuz,_4_March_2019.png, Public Domain. attacks” on Kurdish and Iraqi forces, noting “the towns of Rashad and Hawija west of Kirkuk in particular have seen an uptick in insurgent activity.” The commander notes that on 27 June, twin explosions hit Kirkuk city center, and “ISIS has also claimed responsibility for crop fires on the outskirts of Kirkuk city.” These indicate that ISIS sleeper cells are still present and active in Iraq, especially in Sunni neighborhoods.