Simms, Brendan, and Trim, DJB, Eds. 2011. Humanitarian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections and Reflections, a Professional Autobiography

... • . .... (fcl fa Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the estate of MARION WALKER RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS. RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS OF J. E. PLANCHE, (somerset herald). ^ |]rofcssiona( gaifobbcjrapbtr. " I ran it through, even from my boyish days, To the very moment that he bade me tell it." Othello, Act i., Scene 3. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 18, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND. 1872. ..4^ rights reserved. LONDON BRADBURV, EVANS, AND CO., PRINTERS, WHITBFRIAR,-!. ——— CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. VAGK Another Mission to Paris—Production of " Le Domino Noir"— Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gore—Dinner at Lord Lyndhurst's Mons. Allou, Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of France—The Duke D'Istrie and his Collection of Armour Her Majesty's Coronation—" Royal Records "—Extension of Licence to the Olympic and Adelphi Theatres—" The Drama's Levee"—Trip to Calais with Madame Yestris and Charles Mathews previous to their departure for America—Visit to Tournehem—Sketching Excursion with Charles Mathews Marriage of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews—They sail for New York—The Olympic Theatre opened under my Direc- tion—Farren and Mrs. Nisbett engaged—Unexpected return of Mr. and Mrs. Mathews—Re-appearance of the latter in " Blue Beard "— " Faint Heart never won Fair Lady "—"The Garrick Fever"—Charles Mathews takes Covent Garden Theatre CHAPTER II. Death of Haynes Bayly—Benefit at Drury Lane for his Widow and Family—Letters respecting it from Theodore Hook and Mrs. Charles Gore—Fortunate Results of the Benefit—Tho Honourable Edmund Byng—Annual Dinner established by him in aid of Thomas Dibdin—Mr. -

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, C

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, c. 1515‐1541 by Chad T. Marshall BA (Hons., Archaeology, Toronto), MA (History and Classics, Tasmania) School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, December, 2018 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 i Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 ii Acknowledgements This thesis is for my wife, Elizabeth van der Geest, a woman of boundless beauty, talent, and mystery, who continuously demonstrates an inestimable ability to elevate the spirit, of which an equal part is given over to mastery of that other vital craft which serves to refine its expression. I extend particular gratitude to my supervisors: Drs. Gavin Daly and Michael Bennett. They permitted me the scope to explore the arena of Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland and England, and skilfully trained wide‐ranging interests onto a workable topic and – testifying to their miraculous abilities – a completed thesis. Thanks, too, to Peter Crooks of Trinity College Dublin and David Heffernan of Queen’s University Belfast for early advice. -

HENRY VII M.Elizabeth of York (R.1485–1509)

Historic Royal Places – Descriptors Small Use Width 74mm Wide and less Minimum width to be used 50mm Depth 16.5mm (TOL ) Others Various Icon 7mm Wide Dotted line for scaling Rules 0.25pt and minimum size establishment only. Does not print. HENRY VII m.Elizabeth of York (r.1485–1509) Arthur, m. Katherine HENRY VIII m.(1) Katherine m.(2) Anne m.(3) Jane m.(4) Anne of Cleves Edmund (1) James IV, m Margaret m (2) Archibald Douglas, Elizabeth Mary Catherine Prince of Wales of Aragon* (r.1509–47) Boleyn Seymour (5) Catherine Howard King of Earl of Angus (d. 1502) (6) Kateryn Parr Scotland Frances Philip II, m. MARY I ELIZABETH I EDWARD VI Mary of m. James V, Margaret m. Matthew Stewart, Lady Jane Grey King of Spain (r.1553–58) (r.1558–1603) (r.1547–53) Lorraine King of Earl of Lennox (r.1553 for 9 days) Scotland (1) Francis II, m . Mary Queen of Scots m. (2) Henry, Charles, Earl of Lennox King of France Lord Darnley Arbella James I m. Anne of Denmark (VI Scotland r.1567–1625) (I England r.1603–1625) Henry (d.1612) CHARLES I (r.1625–49) Elizabeth m. Frederick, Elector Palatine m. Henrietta Maria CHARLES II (r.1660–85) Mary m. William II, (1) Anne Hyde m. JAMES II m. (2) Mary Beatrice of Modena Sophia m. Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover m.Catherine of Braganza Prince of Orange (r.1685–88) WILLIAM III m. MARY II (r.1689–94) ANNE (r.1702–14) James Edward, GEORGE I (r.1714–27) Other issue Prince of Orange m. -

Intboduction

INTBODUCTION, 11 IN its main features this History may be described as a continua- tion of " The Custo.mes of London," by Richard Arnold, from which the earlier portion, i.e. as far as the 11th year of Henry VIII., is a mere plagiarism. After that date the Chronicle becomes original, and contains much valuable information. From internal evidence it would appear to be the work of a scholar, and to have been written contemporaneously, the events being jotted down from day to day as they occurred. The characteristic of City Chronicles is maintained throughout by the adoption of the civic year, marking the term of office of each Lord Mayor instead of the regnal year of the sovereign, thus causing an apparent confusion in the chro- nology. This form was probably adopted by our author as he found it already employed by Richard Arnold, whose reign of Henry VII. he made the commencement of his history, with but slight variations, for the reasons subsequently explained. It has therefore been thought advisable to retain this peculiar division of the year in the text, but in the margin the Anno Domini and regnal years have been added in their correct places, so that the reader will experience but little inconvenience from this devia- tion from the ordinary chronology. Whether the author of the Chronicle placed the regnal year in its present position in the text as synonymous with Lord Mayor's Day, or whether it was afterwards transferred thither from the margin by the copyist, is an open question. In the earlier editions of most City Chronicles the name of the new Lord Mayor and sheriffs for the succeeding year are inserted in a blank space in the text left for this purpose in the CAMD. -

Osmanli Kudüsü'nde Toplum Ve Siyaset (1703-1789)

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı OSMANLI KUDÜSÜ’NDE TOPLUM VE SİYASET (1703-1789) Alaattin Dolu Doktora Tezi Ankara, 2017 OSMANLI KUDÜSÜ’NDE TOPLUM VE SİYASET (1703-1789) Alaattin Dolu Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı Doktora Tezi Ankara, 2017 Bu dünyadaki en büyük sermayesi olan sevgisini bana her daim hissettiren ve bu çalışmanın her harfine varlığıyla katkı veren Annem'e v TEŞEKKÜR 2008 yılında başlayan ön inceleme, tetkik ve seyahatlerden sonra ortaya çıkan bu çalışma için çeşitli ülkelerin farklı kurum, kütüphane ve arşivlerinde uzun soluklu araştırma yapıldı. İlk olarak bu çalışma boyunca sekiz yılı geçirdiğim Hacettepe Üniversitesi Tarih Bölümü benim için önemli bir okuldu. Nihâyet bu serüven tamamlandı. Bu bağlamda büyük dedemiz "halka nâfiʽ bir sahs olan" Hacı Hafız Ömer'in ilim yolunda taşıdığı bayrağı devralmak benim için büyük onurdur. Evvela bu çalışmanın ortaya çıkmasında tez hocam Prof. Dr. Mehmet Öz, bu acemi bütünleşik doktora öğrencisinin sorularına cevap verirken hiç usanmadı. Bu anlamda çalışmanın gelişmesinde tavsiyeleriyle yol gösterirken, her daim ilminden istifade etmeme imkân tanıdı. İlâveten, ilim yolunda attığım adımlarda karşıma çıkan engellere karşı kadirşinas kişiliği ve hoşgörüsüyle hep yanımdaydı. Bu vesileyle kendisine şükranlarımı sunuyorum. Bölüm başkanımız Prof. Dr. Ramazan Acun verimli bir çalışma ortamının oluşmasını sağlayarak lisansüstü eğitimimizi tamamlamamızda büyük müsamaha gösterdi. Bölümdeki varlığı benim gibi birçok öğrenci için bir nimet olan Yrd. Doç. Dr. Hulusi Lekesiz bizim için ayaklı biz sözlük idi. Osmanlıca belgelerde karşılaştığımız zorluklarda kapısı her daim açıktı. Teşekkür ederim. Ellinizdeki çalışma son halini alıncaya kadar desteklerini hiç esirgemeyen değerli hocam Prof. Dr. Hülya Taş tez izleme komitesindeki öneri, soru ve en önemlisi teşvikleriyle bana hep güç verdi. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The Israel/Palestine Question

THE ISRAEL/PALESTINE QUESTION The Israel/Palestine Question assimilates diverse interpretations of the origins of the Middle East conflict with emphasis on the fight for Palestine and its religious and political roots. Drawing largely on scholarly debates in Israel during the last two decades, which have become known as ‘historical revisionism’, the collection presents the most recent developments in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict and a critical reassessment of Israel’s past. The volume commences with an overview of Palestinian history and the origins of modern Palestine, and includes essays on the early Zionist settlement, Mandatory Palestine, the 1948 war, international influences on the conflict and the Intifada. Ilan Pappé is Professor at Haifa University, Israel. His previous books include Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988), The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–51 (1994) and A History of Modern Palestine and Israel (forthcoming). Rewriting Histories focuses on historical themes where standard conclusions are facing a major challenge. Each book presents 8 to 10 papers (edited and annotated where necessary) at the forefront of current research and interpretation, offering students an accessible way to engage with contemporary debates. Series editor Jack R.Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University. REWRITING HISTORIES Series editor: Jack R.Censer Already published THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND WORK IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE Edited by Lenard R.Berlanstein SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

Silver, Bells and Nautilus Shells: Royal Cabinets of Curiosity and Antiquarian Collecting

Silver, Bells and Nautilus Shells: Royal cabinets of curiosity and antiquarian collecting Kathryn Jones Curator of Decorative Arts at Royal Collection Trust, London 98 In 1812 James Wyatt, architect to the Prince Regent, was The term Wunderkammer, usually translated as a given instructions to complete the Plate Closet in Carlton ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’, encompassed far more than the House, the Prince’s residence on Pall Mall. The plans traditional piece of furniture containing unusual works of included a large proportion of plate glass. James Wyatt art and items of natural history (fig 1). The concept of a noted this glass although expensive was ‘indispensably Wunderkammer was essentially born in the 16th century necessary, as it is intended that the Plate shall be seen as the princely courts of Europe became less peripatetic and as the Plate is chiefly if not entirely ornamental, and as humanist philosophy spread. The idea was to any glass but Plate [glass] therefore would cripple the create a collection to hold the sum of man’s knowledge. forms and perhaps the most ornamental parts would This was clarified by Francis Bacon in the 17th century 2 be the most injured.’1 The Plate Closet was to be a who stated that the first principle of a ruler was to gather place of wonder, where visitors would be surrounded by together a ‘most perfect and general library’ holding great treasures of wrought silver and gilt. George IV’s every branch of knowledge then published. Secondly a collections, particularly of silver for the Wunderkammer, prince should create a spacious and wonderful garden to show an interest in an area of collecting that was largely contain plants and fauna ‘so that you may have in small unfashionable in the early-nineteenth century and compass a model of universal nature made private’. -

WAGE Women Under

WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 WAGE and Tendencies of German Transatlantic Henry Boyd, afterwards head of Hertford 1908 Enterprise, ; Aktiengesellschaften in Coll. Oxford ; Vicar of Healaugh, Yorkshire, den : Vereinigten Staaten ; Life of Carl Schurz, 1864-71. Publications The Sling and the 1908 Jahrbuch der ; Editor, Weltwirtschaft ; Stone, in 10 vols., 1866-93 ; The Mystery of Address : many essays. The University, Pain, Death, and Sin ; Discourses in Refuta- Berlin. Clubs : of of City New York ; Kaiserl. tion Atheism, 1878 ; Lectures on the Bible, Automobil, Berlin. [Died 28 June 1909. and The Theistic Faith and its Foundations, Baron VON SCHRODER, William Henry, D.L. ; 1881 ; Theism, or Religion of Common Sense, b. 1841 m. d. of ; 1866, Marie, Charles Horny, 1894 ; Theism as a Science of Natural Theo- Austria. High Sheriff, Cheshire, 1888. Ad- logy and Natural Religion, 1895 ; Testimony dress : The Rookery, Worlesden, Nantwich. of the Four Gospels concerning Jesus Christ, 11 all [Died June 1912. 1896 ; Religion for Mankind, 1903, etc. ; Horace St. editor VOULES, George, journalist ; Lecture on Cremation, Mr. Voysey was the of Truth b. ; Windsor, 23 April 1844 ; s. of only surviving founder of the Cremation Charles Stuart of also Voules, solicitor, Windsor. Society England ; he was for 25 years : Educ. private schools ; Brighton ; East- a member of the Executive Council to the bourne. Learned printing trade at Cassell, Homes for Inebriates. Recreations : playing & 1864 started for with children all Fetter, Galpin's, ; them ; games enjoyed except the Echo the first (1868), halfpenny evening chess, which was too hard work ; billiards at and it for until with paper, managed them they home daily, or without a companion ; sold it to Albert Grant, 1875 ; edited and walking and running greatly enjoyed. -

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton Sir William Sydney, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick Soldier and knight and Duke of Northumberland; Earl of renown Marshal. “The minion of his time.” _________|_________ ___________|___ | | | | Lucy, marr. Sir Henry Sydney = Mary Sir Robt. Dudley, William Herbert Sir James three times Lord | the great Earl of 1st E. Pembroke Harrington Deputy of Ireland.| Leicester. Statesman and __________________________|____________ soldier. | | | | Sir Philip Sydney, Sir Robert, Mary = 2d Earl of Pembroke. Scholar, soldier, 1st Earl Leicester, Epitaph | courtier. Soldier & courtier. by Ben | | Johnson | | | Sir Robert, 2d Earl. 3d Earl Pembroke, “Learning, observation, Patron of letters. and veracity.” ____________|_____________________ | | | Philip Sydney, Algernon Sydney, Dorothy, 3d Earl, Patriot. Waller's one of Cromwell's Beheaded, 1683. “Saccharissa.” Council. First published in 1869. Second Edition, with an additional preface, 1892. Fifith corrected proof of the first electronic edition, 2019. Based on the text of the second edition. The page numbering and layout of the second edition have been preserved, as far as possible, to simplify cross-referencing. This is a corrected proof. This document forms part of the archive of Galton material available at http://galton.org. Original electronic conversion by Michal Kulczycki, based on a facsimile prepared by Gavan Tredoux. Many errata were detected by Diane L. Ritter. This edition was edited, cross-checked and reformatted by Gavan Tredoux. HEREDITARY GENIUS AN INQUIRY INTO ITS LAWS AND CONSEQUENCES BY FRANCIS GALTON, F.R.S., ETC. London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1892 The Right of Translation and Reproduction is Reserved CONTENTS PREFATORY CHAPTER TO THE EDITION OF 1892.__________ VII PREFACE ______________________________________________ V CONTENTS __________________________________________ VII ERRATA _____________________________________________ VIII INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. -

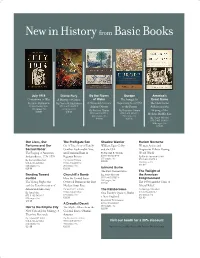

New in History from Basic Books

New in History from Basic Books July 1914 Divine Fury By the Rivers Europe America's Countdown to War A History of Genius of Water e Struggle for Great Game By Sean McMeekin By Darrin M. McMahon A Nineteenth-Century Supremacy, from 1453 e CIA’s Secret 978-0-465-03145-0 9 78-0-465-00325-9 Atlantic Odyssey to the Present Arabists and the 480 pages / hc 360 pages / hc By Erskine Clarke By Brendan Simms $29.99 $29.99 Shaping of the 978-0-465-00272-6 978-0-465-01333-3 Modern Middle East 488 pages / hc 720 pages / hc $29.99 $35.00 By Hugh Wilford 978-0-465-01965-6 384 pages / hc $29.99 Our Lives, Our The Profl igate Son Shadow Warrior Harlem Nocturne Fortunes and Our Or, A True Story of Family William Egan Colby Women Artists and Sacred Honor Con ict, Fashionable Vice, and the CIA Progressive Politics During e Forging of American and Financial Ruin in By Randall B. Woods World War II Independence, 1774-1776 Regency Britain 978-0-465-02194-9 By Farah Jasmine Griffi n 576 pages / hc By Nicola Phillips 978-0-465-01875-8 By Richard Beeman $29.99 978-0-465-02629-6 978-0-465-00892-6 264 pages / hc 528 pages / hc 360 pages / hc $26.99 $29.99 $28.99 Edmund Burke e First Conservative The Twilight of Bending Toward Churchill’s Bomb By Jesse Norman the American How the United States 978-0-465-05897-6 Justice 336 pages / hc Enlightenment e Voting Rights Act Overtook Britain in the First $27.99 e 1950s and the Crisis of and the Transformation of Nuclear Arms Race Liberal Belief American Democracy By Graham Farmelo The Rainborowes By George Marsden By Gary May 978-0-465-02195-6 One Family’s Quest to Build 978-0-465-03010-1 576 pages / hc 240 pages / hc 978-0-465-01846-8 a New England 336 pages / hc $29.99 $26.99 $28.99 By Adrian Tinniswood 978-0-465-02300-4 A Dreadful Deceit 384 pages / hc Heir to the Empire City e Myth of Race from the $28.99 New York and the Making of Colonial Era to Obama’s eodore Roosevelt America By Edward P.