30Th General Report of the CPT (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological and Mineralogical Sciences

22 Geological and Mineralogical sciences dAILY ACTIvITY OF MUd vOLCANOES ANd GEOECOLOGICAL RISK: A CASE FROM GAYNARJA MUd vOLCANO, AZERBAIJAN 1Baloglanov E.E., 1Abbasov O.R., 1Akhundov R.V., 1Huseynov A.R., 2Abbasov K.A., 3Nuruyev I.M. 1Institute of Geology and Geophysics of the National Academy of Sciences, Baku; 2Azerbaijan State Pedagogical University; 3Institute of Radiation Problems of the Azerbaijani National Academy of Sciences, Baku, e-mail: [email protected] “Mud volcanic activity and geoecological risk” problem was studied using visual, satellite, geological, geo- chemical and radioactive research on the example of a mud volcano Gaynarja located near the Tahtakorpu Water Reservoir. From the viewpoint of the considered relationship, the studies results make possible to think about the probability of a risk factor on several aspects: The reservoir was built in 2007, and to this day the water area has been expanding without taking into account the necessary distance from the mud volcano. Excluding the north-eastern part the mud volcano, other sides of its crater buried beneath the Reservoir water. Due to the daily activity of the mud volcano, heavy toxic metals, gases, radioactive elements and etc. have been ejecting to the Earth’s surface in the compositions of various phase of volcanic products and directly contact with the Reservior water. Expansion the Reservoir area and water volume leads to increase in additional geostatistical pressure in volcanic area. In addition, the mud volcano is located near the Shamakhi-Ismayilli active seismic zone in Azerbaijan. Both factors increase the eruption risk the volcano that has been “asleep” for many years. -

Dips Салати | Salads Супа | Soup Предястия | Appetizers

РАЗЯДКИ | DIPS g BGN Тиро 150 6.00 Tiro Хумус 150 6.00 Hummus Кьопоолу 150 6.00 Eggplant caviar Tарама хайвер 150 6.00 Tarama caviar САЛАТИ | SALADS Шопска 250 9.00 Shopska домати, краставици, сирене, tomatoes, cucumbers, white cheese, пресен пипер, лук, маслини peppers, onion, olives Дзадзики 250 8.00 Dzadziki цедено кисело мляко, strained yoghurt, cucumbers, краставици, мента, зехтин mint, olive oil Табуле 250 8.00 Tabbouleh булгур, магданоз, домат, bulgur, tomatoes, parsley, чесън, зехтин, лимон garlic, olive oil, lemon Печен пипер 250 9.00 Roasted peppers катък, чесън, зехтин garlic, cream cheese, olive oil СУПА | SOUP Рибена супа 250 7.00 Fish soup ПРЕДЯСТИЯ | APPETIZERS Запечено халуми с домат 150 10.00 Grilled Halloumi with tomatoes Хрупкави тиквички 200 7.00 Crispy zucchini Хрупкави калмари 200 9.00 Fried crispy calamari Миди с чили 300 10.00 Mussels with chili Пържен сафрид 200 11.00 Fried scad fish Пържен патладжан 250 9.00 Fried eggplant with с доматен сос и сирене фета tomato sauce and feta cheese Пържен свински дроб 200 8.00 Fried pork liver Патешки сърца 250 8.00 Fried duck hearts БАРБЕКЮ | BARBECUE g BGN Пилешко филе 250 12.00 Chicken fillet Свинска вратна пържола 250 15.00 Pork neck steak Свинско шишче 100 6.00 Pork skewer Пилешко шишче 100 6.00 Chicken skewer Телешки шиш кебап 250 16.00 Beef kebap Телешки карначета 200 12.00 Beef sausages Агнешки кюфтета 180 12.00 Lamb meat balls Адана кебап 200 14.00 Adana kebap Плескавица 250 13.00 Pleskavitsa Ястията, приготвени на барбекю, се сервират с гарнитура арабски булгур, запечен -

Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 39176 January 2007 Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement Prepared by the Road Transport Service Department for the Asian Development Bank. The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. 2 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 2 January 2007) Currency Unit – Azerbaijan New Manat/s (AZM) AZM1.00 = $1.14 $1.00 = AZM0.87 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DRMU – District Road Maintenance Unit EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESS – Ecology and Safety Sector IEE – initial environmental examination MENR – Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources MFF – multitranche financing facility NOx – nitrogen oxides PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance ROW – right-of-way RRI – Rhein Ruhr International RTSD – Road Transport Service Department SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SOx – sulphur oxides TERA – TERA International Group, Inc. UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WHO – World Health Organization WEIGHTS AND MEASURES C – centigrade m2 – square meter mm – millimeter vpd – vehicles per day CONTENTS MAP I. Introduction 1 II. Description of the Project 3 IIII. Description of the Environment 11 A. Physical Resources 11 B. Ecological and Biological Environment 13 C. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD1591 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT PAPER FOR AN Public Disclosure Authorized ADDITIONAL LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$66.7 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN FOR THE IDP LIVING STANDARDS AND LIVELIHOODS PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 17, 2016 Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice Europe and Central Asia Region This document is being made publicly available prior to Board consideration. This does not imply a presumed outcome. This document may be updated following Board consideration and the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s policy on Access to Information. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective May 20, 2016) Currency Unit = New Azerbaijani Manat (AZN) AZN 1.49 = US$1 US$0.71 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AF Additional Financing CPF Country Partnership Framework ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework FM Financial Management GoA Government of Azerbaijan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism GRS Grievance Redress Service IDP Internally Displaced Person IFR Interim Financial Report O&M Operations and Maintenance OM Operational Manual PDO Project Development Objective PIU Project Implementation Unit RAP Resettlement Action Plan RPF Resettlement Policy Framework SFDI Social Fund for the Development of IDPs Vice President: Cyril E Muller Country Director: Mercy Miyang Tembon Senior Global Practice Director: Ede Jorge Ijjasz-Vasquez Country Manager: Larisa Leshchenko Practice Manager: Nina Bhatt Task Team Leader: Michelle P. Rebosio Calderon REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ADDITIONAL FINANCING TO IDP LIVING STANDARDS AND LIVELIHOODS PROJECT (P155110) CONTENTS Project Paper Data Sheet i Project Paper I. -

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) 677-686 Download

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Linzer biologische Beiträge Jahr/Year: 2017 Band/Volume: 0049_1 Autor(en)/Author(s): Maharramova Sheyda Mamed, Ayberk Hamit Artikel/Article: New records of leafrollers reared in Azerbaijan (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) 677-686 download www.zobodat.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 49/1 677-686 28.7.2017 New records of leafrollers reared in Azerbaijan (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Sheyda MAHARRAMOVA & Hamit AYBERK A b s t r a c t : 17 species of tortricid moths had been defined for the eastern parts of Azerbaijan during the years of 1994-2015. Five of these, Ptycholoma lecheana (LINNAEUS, 1758), Cacoecimorpha pronubana HÜBNER, 1799, Eudemis profundana ([DENIS & SCHIFFERMÜLLER], 1775), Hedya salicella (LINNAEUS, 1758), and Epinotia demarniana (FISCHER VON RÖSLERSTAMM, 1840), are new to the Azerbaijan fauna; two of them (Cacoecimorpha pronubana and Epinotia demarniana) are new to the Caucasian fauna, as well. Leafrollers were collected in the larval and pupal stage from March to September on their food plants according to the sampling methods. The early stages were kept in the laboratory until adult emergence, after which they were killed and pinned. Data on newly recorded leafrollers are given in the text including species name, collection area, coordinates of area, data of collection, food plants on which they were recorded, and sex of specimen(s). Key words: Tortricids, damage, host plants, Azerbaijan, fauna. Introduction Tortricidae, commonly known as leafrollers, are one of the most diverse families in the Microlepidoptera. The number of leafroller species in countries bordering Azerbaijan differs among the adjacent regions: 469 species are recorded from Turkey (KOÇAK & KEMAL 2012), 145 species from Iran (KOÇAK & KEMAL 2012), and 139 species from Georgia (ESARTIA 1988). -

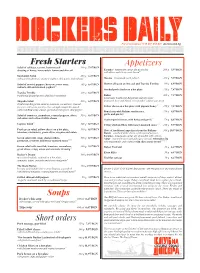

DC 20 MENU ENG 2010 31.Cdr

For reservations +359 887 005 007 dockersclub.bg Fresh Starters Appetizers Salad of cabbage, carrots, beetroot and 300 g 5,97 BGN dressing of honey, horseradish, lemon and olive oil Tarama - homemade caviar dip of sea fish 200 g 5,97 BGN with olives and slices rustic bread1,4 Snezhanka Salad 250 g 6,47 BGN with pickled gherkins, strained yoghurt, dill, garlic and walnuts7,8 Slanina - homemade pork fatback 100 g 5,97 BGN Salad of roasted peppers, beetroot, sweet corn, 180 g 6,47 BGN Skewer of bacon on live coal and Tsarska Тurshia 180 g 6,97 BGN walnuts, dill and strained yoghurt7,8 Smoked pork cheeks on a hot plate 150 g 7,47 BGN Tsarska Тurshia 200 g 6,47 BGN traditional Bulgarian mix of pickled vegetables Bahur 200 g 7,47 BGN homemade traditional Bulgarian sausage made Shopska Salad 300 g 6,97 BGN from pork liver and blood, served either cold or pan-fried Traditional Bulgarian salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, roasted 1,7 peppers, red onion, parsley, olive oil and vinaigrette, mixed Yellow cheese on a hot plate with piquant honey 150 g 7,47 BGN with crumbled white cheese, garnished with green chili pepper7 Bruschetta with Boletus mushrooms, 150 g 8,97 BGN 1,7 Salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, roasted peppers, olives, 350 g 8,47 BGN garlic and parsley 7 red onion and a slice of white cheese 7 Veal tongue in butter, with herbs and garlic 120 g 8,97 BGN 7,8 Caprese Salad 300 g 8,97 BGN Crispy chicken fillets with honey-mustard sauce1,3,10 220 g 9,97 BGN Fresh green salad, yellow cheese on a hot plate, 300 g 8,97 BGN 7 Plate of traditional appetizers -

Intergovernmental Conference on the Accession of the Republic of Bulgaria to the European Union

CONFERENCE ON ACCESSION Brussels, 6 July 2001 TO THE EUROPEAN UNION - BULGARIA - CONF-BG 43/01 DOCUMENT PROVIDED BY BULGARIA INTERGOVERNMENTAL CONFERENCE ON THE ACCESSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA TO THE EUROPEAN UNION NEGOTIATING POSITION ON CHAPTER 7 AGRICULTURE 20486/01 CONF-BG 43/01 1 EN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS______________________________________________________________________________4 OVERALL POSITION __________________________________________________________________________5 HORIZONTAL MEASURES _____________________________________________________________________5 EUROPEAN AGRICULTURAL GUIDANCE AND GUARANTEE FUND (EAGGF)__________________________________5 GUARANTEE SECTION _____________________________________________________________________________5 GUIDANCE SECTION_______________________________________________________________________________6 TRADE MECHANISMS_____________________________________________________________________________6 LICENSING SYSTEM _______________________________________________________________________________6 EXPORT REFUNDS ________________________________________________________________________________7 CUSTOMS TARIFF_________________________________________________________________________________7 QUALITY POLICY ________________________________________________________________________________7 SPREADABLE FATS_______________________________________________________________________________10 ORGANIC FARMING _____________________________________________________________________________10 FADN________________________________________________________________________________________11 -

Culture of Azerbaijan

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CULTURE OF AZERBAIJAN CONTENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................................................................................................. 3 II. MATERIAL CULTURE ................................................................................................................... 5 III. MUSIC, NATIONAL MUSIC INSTRUMENTS .......................................................................... 7 Musical instruments ............................................................................................................................... 7 Performing Arts ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Percussion instruments ........................................................................................................................... 9 Wind instruments .................................................................................................................................. 12 Mugham as a national music of Azerbaijan ...................................................................................... 25 IV. FOLKLORE SONGS ..................................................................................................................... 26 Ashiqs of Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 27 V. THEATRE, -

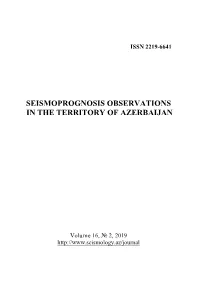

Seismoprognosis Observations in the Territory of Azerbaijan

ISSN 2219-6641 SEISMOPROGNOSIS OBSERVATIONS IN THE TERRITORY OF AZERBAIJAN Volume 16, № 2, 2019 http://www.seismology.az/journal Republican Seismic Survey Center of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences SEISMOPROGNOSIS OBSERVATIONS IN THE TERRITORY OF AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL EDITORIAL BOARD BOARD G.J.Yetirmishli (chief editor) A.G.Aronov (Belarus) R.M.Aliguliyev (Baku, Azerbaijan) T.L.Chelidze (Georgia) F.A.Aliyev (Baku, Azerbaijan) Rengin Gok (USA) T.A.Aliyev (Baku, Azerbaijan) Robert van der Hilst (USA F.A.Gadirov (Baku, Azerbaijan) Massachusetts) H.H.Guliyev (Baku, Azerbaijan) A.T.Ismayilzadeh (Germany) I.S.Guliyev (Baku, Azerbaijan) R.Javanshir (Great Britain) T.N.Kengerli (Baku, Azerbaijan) A.V.Kendzera (Ukraine) P.Z.Mammadov (Baku, Azerbaijan) A.A.Malovichko (Russia) T.Y. Mammadli (Baku, Azerbaijan) Robert Mellors (USA Livermore) H.O. Valiyev (Baku, Azerbaijan) X.P.Metaxas (Greece) E.A.Rogozhin (Russia) Eric Sandvol (USA Missouri) L.B.Slavina (Russia) N.Turkelli (Turkey) Responsible Secretary: Huseynova V.R. SEISMOPROGNOSIS OBSERVATIONS IN THE TERRITORY OF AZERBAIJAN, V. 16, №2, 2019, pp. 3-7 3 ASSESSMENT OF SEISMIC HAZARD IN THE TERRITORY OF “TAKHTAKORPU” RESERVOIR OF AZERBAIJAN G.J. Yetirmishli1, T.Y. Mammadli1, R.B. Muradov1, T.I. Jaferov1 Takhtakorpu reservoir and the relevant dam complex’s territories are located in the Darachay valley (Takhtakorpu), 3.5 km south-west of Shabran. The area of the dam and reservoir is characterized by smooth heights that are not too high, numerous ravines, complicated hills and sloping plains. The absolute height of the surface is within 60-2500 m, here. There is Gaynarcha mud volcano with an absolute height of 180 m in the abyssal mountain shore of Takhtakorpu river, 2 km from the dam. -

2009 Trial Monitoring Report Azerbaijan N a J I a B R E Z A

2009 TRIAL MONITORING REPORT AZERBAIJAN REPOR 2009 TRIAL T AZERBAIJAN MONIT ORING 2009 TRIAL MONITORING REPORT AZERBAIJAN © OSCE Office in Baku - i - Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................ ii List of Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Scope of the Report. Methodology............................................................................................................... 6 I. Observance of Fair Trial and Rights of the Defendants....................................................................... 9 1.1. The Right to a Public Hearing..................................................................................................... 9 1.2. Presence at Hearings: Defendant, Defence Counsel and Prosecutor ........................................ 11 1.3. The Right to be Informed of the Charges and the Right not to Incriminate Oneself ................ 13 1.4. Duty to Effectively Investigate Allegations of Ill-Treatment ................................................... 21 1.5. The Right to an Independent and Impartial Tribunal................................................................ 25 1.6. The Right to be Presumed Innocent......................................................................................... -

Official Transcript.Pdf

HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN AZERBAIJAN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 29, 2008 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 110–2–19] ( Available via http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63–897 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:13 Jan 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\WORK\072908.TXT KATIE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida, BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland, Chairman Co-Chairman LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin New York CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut MIKE McINTYRE, North Carolina HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York HILDA L. SOLIS, California JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts G.K. BUTTERFIELD, North Carolina SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GORDON SMITH, Oregon ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MIKE PENCE, Indiana EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS DAVID J. KRAMER, Department of State MARY BETH LONG, Department of Defense DAVID BOHIGIAN, Department of Commerce (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:13 Jan 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\WORK\072908.TXT KATIE HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN AZERBAIJAN JULY 29, 2008 COMMISSIONERS Page Hon.