Activist Perspectives on the Australian Anti-Capitalist Movement Tom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

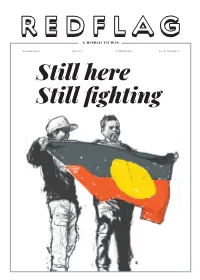

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13804-8 - Labor’s Conflict: Big Business, Workers and the Politics of Class Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn Frontmatter More information LABOR’S CONFLICT Big business, workers and the politics of class Once widely regarded as the workers’ greatest hope for a better world, the ALP today would rather project itself as a responsible manager of Australian capitalism. Labor’s Conflict: Big Business, Workers and the Politics of Class provides an insightful account of the transformations in the Party’s policies, performance and structures since its formation. Seasoned political analysts Tom Bramble and Rick Kuhn offer an inci- sive appraisal of the Party’s successes and failures, betrayals and electoral triumphs in terms of its competing ties with bosses and workers. The early chapters outline diverse approaches to understanding the nature of the Party and then assess the ALP’s evolution in response to major social upheavals and events, from the strikes of the 1890s, through two World Wars, the Great Depression, and the post-war boom. The records of the Whitlam, Hawke, Keating, Rudd and Gillard governments are then dissected in detail. The compelling conclusion offers alternatives to the Australian Labor Party, for those interested in progressive change. Tom Bramble is Senior Lecturer in Industrial Relations in the School of Business at the University of Queensland. Rick Kuhn is Reader in Political Science in the School of Politics and Inter- national Relations at the Australian National University. © in this web -

Commonwealth Responsibility and Cold War Solidarity Australia in Asia, 1944–74

COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 DAN HALVORSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463236 ISBN (online): 9781760463243 WorldCat (print): 1126581099 WorldCat (online): 1126581312 DOI: 10.22459/CRCWS.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A1775, RGM107. This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix 1 . Introduction . 1 2 . Region and regionalism in the immediate postwar period . 13 3 . Decolonisation and Commonwealth responsibility . 43 4 . The Cold War and non‑communist solidarity in East Asia . 71 5 . The winds of change . 103 6 . Outside the margins . 131 7 . Conclusion . 159 References . 167 Index . 185 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Cathy Moloney, Anja Mustafic, Jennifer Roberts and Lucy West for research assistance on this project. Thanks also to my colleagues Michael Heazle, Andrew O’Neil, Wes Widmaier, Ian Hall, Jason Sharman and Lucy West for reading and commenting on parts of the work. Additionally, I would like to express my gratitude to participants at the 15th International Conference of Australian Studies in China, held at Peking University, Beijing, 8–10 July 2016, and participants at the Seventh Annual Australia–Japan Dialogue, hosted by the Griffith Asia Institute and Japan Institute for International Affairs, held in Brisbane, 9 November 2017, for useful comments on earlier papers contributing to the manuscript. -

Corporatism As a Process of Working-Class Containment and Roll-Back: the Recent Experiences of South Africa and South Korea

Corporatism as a process of working-class containment and roll-back: The recent experiences of South Africa and South Korea Tom Bramble School of Business University of Queensland Brisbane Q 4072 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] and Neal Ollett This paper has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Industrial Relations and the final version of this paper will be published in the Journal of Industrial Relations vol. 49, issue 4, September 2007 by Sage Publications Ltd. All rights reserved. © For more information please visit: www.sagepublications.com. ABSTRACT In this article we argue that recent debates in the corporatist literature about whether corporatism is best understood as a process of structured interest representation or political dialogue miss the point as to corporatism’s central task – the shift of material resources and power away from the working class to the capitalist class, in which two processes are evident – containment and roll- back. We discuss these processes in the context of successive waves of corporatism in Western Europe from the 1940s to the 1990s before moving on to an analysis of the contrasting fortunes of corporatism in South Africa and South Korea during democratic transition. We conclude that the ability of corporatism to carry out the processes of containment and roll back in these two cases have been dependent on the existence (or absence) of supportive prior political relationships between organised labour and the state. Corporatism as a process of working-class containment and roll-back: The recent experiences of South Africa and South Korea INTRODUCTION Traditional interpretations of corporatism have focused on institutionalised structures of interest representation (Molina and Rhodes, 2002). -

The Globalisation of the Pharmaceutical Industry

The Globalisation of the Pharmaceutical Industry PHARMACEUTICALS POLICY AND LAW Pharmaceuticals Policy and Law Volume 18 Earlier published in this series Vol.1. J.L. Valverde and G. Fracchia (Eds), Focus on Pharmaceutical Research Vol.2. J.L. Valverde (Ed), The Problem of Herbal Medicines Legal Status Vol.3. J.L. Valverde (Ed), The European Regulation on Orphan Medicinal Products Vol.4. J.L. Valverde (Ed), Information Society in Pharmaceuticals Vol.5. C. Huttin (Ed), Challenges for Pharmaceutical Policies in the 21st Century Vol.6. J.L. Valverde and P. Weissenberg (Eds), The Challenges of the New EU Pharmaceutical Legislation Vol.7. J.L. Valverde (Ed), Blood, Plasma and Plasma Proteins: A Unique Contribution to Modern Healthcare Vol.8. J.L. Valverde (Ed), Responsibilities in the Efficient Use of Medicinal Products Vol.9(1,2). J.L. Valverde (Ed), 2050: A Changing Europe. Demographic Crisis and Baby Friend Policies Vol.9(3,4). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Key Issues in Pharmaceuticals Law Vol.10. J.L. Valverde and D. Watters (Eds), Focus on Immunodeficiencies Vol.11(1,2). J.L. Valverde and A. Ceci (Eds), The EU Paediatric Regulation Vol.11(3). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Health Fraud and Other Trends in the EU Vol.11(4). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Rare Diseases: Focus on Plasma Related Disorders Vol.12(1,2). J.L. Valverde and A. Ceci (Eds), Innovative Medicine: The Science and the Regulatory Framework Vol.12(3,4). J.L. Valverde (Ed), New Developments of Pharmaceutical Law in the EU Vol.13(1,2). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Challenges for the Pharmaceuticals Policy in the EU Vol.14(1). -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Bioethics

Solidarity: reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx This report was commissioned by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCoB) and was jointly funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Nuffield Foundation. The award was managed by the Economic and Social Research Council on behalf of the partner organisations, and some additional funding was made available by NCoB. For the duration of six months in 2011, Professor Barbara Prainsack was the NCoB Solidarity Fellow, working closely with fellow author Dr Alena Buyx, Assistant Director of NCoB. Disclaimer The report, whilst funded jointly by the AHRC, the Nuffield Foundation and NCoB, does not necessarily express the views and opinions of these organisations; all views expressed are those of the authors, Professor Barbara Prainsack and Dr Alena Buyx. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is an independent body that examines and reports on ethical issues in biology and medicine. It is funded jointly by the Nuffield Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, and has gained an international reputation for advising policy makers and stimulating debate in bioethics. www.nuffieldbioethics.org The Nuffield Foundation is an endowed charitable trust that aims to improve social wellbeing in the widest sense. It funds research and innovation in education and social policy and also works to build capacity in education, science and social science research. www.nuffieldfoundation.org Established in April 2005, the AHRC is a non-Departmental public body. It supports world-class research that furthers our understanding of human culture and creativity. www.ahrc.ac.uk © Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx ISBN: 978-1-904384-25-0 November 2011 Printed in the UK by ESP Colour Ltd. -

Resisting Howard's Industrial Relations

RESISTING HOWARD’S INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS ‘REFORMS’: AN ASSESSMENT OF ACTU STRATEGY Tom Bramble ‘We are facing the fight of our lives. The trade union movement will be judged on how effectively we meet this challenge’ (AMWU National Secretary, Doug Cameron, May 2005). Howard’s planned industrial relations (IR) legislation confronts Australian unions with their worst nightmare. This is obviously the case for rank and file members who face a savage attack on their conditions, but the legislation is also terrifying for the union bureaucracy. Since Federation, Australian capitalism has operated on the basis of mediating class conflict at the workplace through arbitration and conciliation. This did not mean that class conflict was absent, or that the arbitration system was not itself a weapon in this conflict, only that at the base of any such conflict was a recognition by employers and the state of the legitimacy of the union bureaucracy in the industrial relations process. With its WorkChoices legislation, the Howard government has signalled an onslaught on this entire system and, with it, the central role of union officials in the system of structured class relationships. The purpose of this article is to provide a critical assessment of the strategy drawn up by the ACTU to resist WorkChoices. Although there are differences of emphasis within their ranks, the ACTU executive and office bearers have pursued a strategy with five main components. First, to convince employers that they are wrong to break from the system that has served them well for a century. Second, to lobby the ALP at state and federal levels. -

066728 Bramble 31/5/06 3:13 Pm Page 289

066728 Bramble 31/5/06 3:13 pm Page 289 ‘Another world is possible’ A study of participants at Australian alter-globalization social forums Tom Bramble University of Queensland Abstract The past decade has seen the emergence of a mass ‘alter-globalization’ move- ment in many regions of the world. One element in this movement has been the World Social Forum and its continental, regional, national and local spin- offs. In the first half of this article I provide a critical analysis of the social forum experience, particularly the World Social Forum, and outline both those aspects of the experience that are commonly agreed to be successes as well as those that are frequently held to be their failings or limitations. In the sec- ond half of the article, I report on a survey of the participants at two Australian social forums in 2004, which details their backgrounds, motivations, attitudes, experience and ambitions. Comparison is made with their closest parallels – the activists from the new social movements of the 1970s and 1980s previ- ously examined by Offe, Touraine, Melucci and others. Keywords: anti-globalization, new social movements, World Social Forum The accelerating processes of economic and financial globalization have transformed the world economy in the past two decades. These processes have challenged the capacities and practices of key institutions, both national (such as governments, central banks and trade unions) and transnational (such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund [IMF] and transnational companies [TNCs]). By the same token, globaliza- tion has confronted communities in both the West and the developing world with a range of systemic problems arising out of the unchecked power of international capitalism. -

Practices of Refugee Support Between Humanitarian Help And

Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Culture and Social Practice Larissa Fleischmann, born in 1989, works as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Human Geography at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. She received her PhD from the University of Konstanz, where she was a member of the Centre of Excellence »Cultural Foundations of Social Integration« and the Social and Cultu- ral Anthropology Research Group from 2014 to 2018. Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism Dissertation of the University of Konstanz Date of the oral examination: February 15, 2019 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. Thomas G. Kirsch 2nd reviewer: PD Dr. Eva Youkhana 3rd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Judith Beyer This publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Re- search Foundation) - Project number 448887013. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The field research for this publication was funded by the Centre of Excellence “Cultural Foundations of Social Integration”, University of Konstanz. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY- NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. For details go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Permission to use the text for commercial purposes can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

SOCIAL DEMOCRACY and the "FAILURE" of the ACCORD Tom

SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE "FAILURE" OF THE ACCORD Tom Bramble School of Business University of Queensland Brisbane Q 4072 AUSTRALIA [email protected] Published in K. Wilson, J. Bradford, and M. Fitzpatrick (eds) (2000): Australia in Accord: An Evaluation of the Prices and Incomes Accord in the Hawke-Keating Years, South Pacific Publishing, Melbourne, pp.243-64. 2 SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE "FAILURE" OF THE ACCORD1 INTRODUCTION Most sections of the industrial relations academic community (broadly defined) started with favourable impressions of the ALP-ACTU Prices and Incomes Accord. Amongst its keenest and most articulate supporters were academics and unionists writing from an explicitly social democratic perspective. Frequently drawing on the German and Scandinavian experiences, writers such as Hughes (1981), Hartnett (1981), Higgins (1978, 1980, 1985), Stilwell (1982), Burford (1983), Ogden (1984), Mathews (1986), and Clegg et al (1986) argued that the Accord would enable the union movement to break out of its labourist straitjacket to encompass broader political concerns and to develop a social role well beyond the ranks of organised labour.2 Similarly it was the left unions such as the Building Workers Industrial Union (BWIU) and Metal Workers Union (AMWU) who were most successful in developing an ideological underpinning for the Accord within the labour movement and who were most influential in winning support for it amongst workers who had the capacity to render it impotent. Opponents of the Accord at the time were almost entirely limited to Left organisations outside the Labor and Communist Parties (below) and a minority of right-wing commentators (for example Terry McCrann in The Age), the former on the basis that it represented an attack on wages and workers' rights under the rubric of social justice, the latter that it did not attack unions hard enough. -

Current Anthropology October 2015 Volume 56 Supplement 11 Pages S1–S180

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Current Anthropology Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) VOLUME 56 SUPPLEMENT 11 OCTOBER 2015 The Life and Death of the Secret. Lenore Manderson, Mark Davis, and Current Chip Colwell, eds. Reintegrating Anthropology: From Inside Out. Agustín Fuentes and Polly Wiessner, eds. Anthropology Previously Published Supplementary Issues Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. Thomas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and October 2015 Sally Engle Merry, eds. POLITICS OF THE URBAN POOR: AESTHETICS, Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. ETHICS, VOLATILITY, PRECARITY The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. T. Douglas Price and GUEST EDITORS: VEENA DAS AND SHALINI RANDERIA Ofer Bar-Yosef, eds. The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, Politics of the Urban Poor: Aesthetics, Ethics, Volatility, Precarity National Styles, and International Networks. Susan Lindee and 56 Volume The Urban Poor and Their Ambivalent Exceptionalities: Notes from Jakarta Ricardo Ventura Santos, eds. The Politics of Not Studying the Poorest of the Poor in Urban South Africa Human Biology and the Origins of Homo. Susan Antón and Leslie C. Plebeians of the Arab Spring Aiello, eds. Political Leadership and the Urban Poor: Local Histories Potentiality and Humanness: Revisiting the Anthropological Object in The Need for Patience: The Politics of Housing Emergency in Buenos Aires Contemporary Biomedicine. Klaus Hoeyer and Karen-Sue Taussig, eds. The Politics of the Urban Poor in Postwar Colombo Supplement 11 Alternative Pathways to Complexity: Evolutionary Trajectories in the Middle Sectarianism and the Ambiguities of Welfare in Lebanon Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age.