Neo Impressionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form

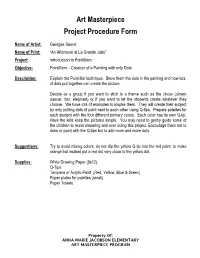

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form Name of Artist: Georges Seurat Name of Print: “An Afternoon at La Grande Jatte” Project: Introduction to Pointillism Objective: Pointillism – Creation of a Painting with only Dots Description: Exlplain the Pointillist technique. Show them the dots in the painting and how lots of dots put together can create the picture. Decide as a group if you want to stick to a theme such as the circus (clowm dancer, lion, elephant) or if you want to let the students create whatever they choose. We have lots of examples to inspire them. They will create their subject by only putting dots of paint next to each other using Q-tips. Prepare palettes for each student with the four different primary colors. Each color has its own Q-tip. Have the kids keep the pictures simple. You may need to gently guide some of the children to resist smearing and over doing this project. Encourage them not to draw or paint with the Q-tips but to add more and more dots. Suggestions: Try to avoid mixing colors, do not dip the yellow Q-tip into the red paint, to make orange but instead put a red dot very close to the yellow dot. Supplies: White Drawing Paper (9x12) Q-Tips Tempera or Acrylic Paint (Red, Yellow, Blue & Green) Paper plates for palettes (small) Paper Towels Property Of: ANNA MARIE JACOBSON ELEMENTARY ART MASTERPIECE PROGRAM Georges Seurat (Zhorzh Soo-Rah) Seurat was born in 1859 in Paris. He was the son of a comfortably situated middle class family. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

Degas: a New Vision and Seurat's Circus Sideshow

Michelle Foa exhibition review of Degas: A New Vision and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Citation: Michelle Foa, exhibition review of “Degas: A New Vision and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017), https://doi.org/ 10.29411/ncaw.2017.16.2.13. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Foa: Degas: A New Vision and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Degas: A New Vision Museum of Fine Arts, Houston October 16, 2016 – January 16, 2017 Previously at: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne June 24 – September 18, 2016 Seurat’s Circus Sideshow The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York February 17 – May 29, 2017 Catalogues: Degas: A New Vision. Henri Loyrette. Melbourne, Victoria: Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, 2016. 287 pp.; color illus.; bibliography; checklist. $35 ISBN: 9781925432114 Seurat’s Circus Sideshow. Richard Thomson, with contributions by Susan Alyson Stein, Charlotte Hale, and Silvia A. Centeno. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017. 144 pp.; 117 color illus.; bibliography; checklist; index. $30 ISBN: 9781588396150 Edgar Degas and Georges Seurat exhibited together only once, at the eighth and final Impressionist show in the spring of 1886. At that moment, Seurat was moving to the forefront of Paris’s modern art world, and A Sunday on the Grande Jatte–1884 (1884–86) would soon become a landmark in modern French painting. -

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

09.10.2010 ART IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: IMPRESSIONISM AND POST-IMPRESSIONISM Week 2 WORLD HISTORY ART HISTORY ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY Marx and Engels issue Communist Manifesto, 1848 Smirke finished British Museum Gold discovered in California 1849 The Stone Broker, Courbet 1850 Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve (Neo- Renaissance) 1852 The Third Class Carriage by Daumier Houses of Parliment, London (Neo-Gothic) 1854 Crystal Palace, First cast-iron and glass structure 1855 Courbet’s Pavillion of Realism Flaubert writes Madame Bovary 1856-1857 Mendel begins genetic experiments 1857 REALISM First oil well drilled, 1859-60 Red House by Philip Webb (Arts &Crafts) Darwin publishes Origin of Spaces Steel developed 1860 Snapshot photography developed U.S. Civil War breaks out 1861 Corot Painted Orpheus Leading Eurydice 1862 Garnier built Paris Opera (Neo-Baraque) Lincoln abolishes slavery 1863 Manet painted Luncheon on the Grass Suez Canal built 1869 Prussians besiege Paris 1871 1873 First color photos appear IMPRESSIONISM 1874 Impressionists hold first group show Custer defeated at Little Big Horn, 1876 Bell patents telephone Edison invents electric light 1879 1880 VanGogh begins painting career Population of Paris hits 2,200,000 1881 1882 Manet painted A Bar at the Folies-Bergère 1883 Monet settles at Giverny First motorcar built 1885 First Chicago Skyscraper built 1886 Impressionists hold last group show 1888 Portable Kodak camera perfected Hitler born 1889 Eiffel Tower built 1901 1902 1903 POSTIMPRESSIONISM 1905 1 09.10.2010 REALISM VALUES: Real , Fair, Objective INSPIRATION: The Machine Age, Marx and Engel’s Communist Manifesto, Photography, Renaissance art TONE: Calm, rational, economy of line and color SUBJECTS: Facts of the modern world, as the artist experienced them; Peasants and the urban working class; landcape; Serious scenes from ordinary life, mankind. -

Pittura Ideista: the Spiritual in Divisionist Painting1

Pittura ideista: The Spiritual in Divisionist Painting1 Vivien Greene The Divisionists were a loosely associated group of late-nineteenth-century painters intent on creating a distinctly Italian avant-garde art. Their mission was underpinned by modernist and nationalist aspirations,2 while their painting method drew on scientific theories of optics and chromatics and relied on the application of brushstrokes of individual, often complementary, colors to craft shimmering surfaces that capitalized on light effects.3 Although the movements’ members generally aligned I am grateful to those who read this essay: firstly, at its inception, Giovanna Ginex, more recently, Jon Snyder, and, lastly, my anonymous readers. I am also thankful to all my colleagues at the museums and archives named herein who gave me access to artworks and documents and supported my research efforts, even long distance. 1 This article is a recast and expanded version of an earlier essay of mine, “Divisionism’s Symbolist Ascent,” in Radical Light: Italy’s Divisionist Painters, 1891-1910 (exh. cat.), ed. Simonetta Fraquelli (London: National Gallery; Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich, 2008), 47-59. My title borrows from a term that the Divisionist artist and critic Vittore Grubicy De Dragon developed to differentiate Italian Symbolism from similar tendencies among other artists and in other nations, calling it pittura ideista. See especially Vittore Grubicy De Dragon, “Pittura Ideista,” in Prima esposizione triennale Brera 1891. Tendenze evolutive nelle arti plastiche: Pensiero italiano 9 (Milan: Tipografia Cooperativa Insubria, 1891), 47-50. Grubicy’s moniker was probably inspired by G.-Albert Aurier’s concept of “art idéiste,” a term bandied about then, which was most famously discussed in his “Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin,” Mercure de France 2 (March 1891): 155-64. -

(At the Cirque Fernando) by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec

Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) 1887–1888 By Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO Department of Museum Education Division of Teacher Programs Crown Family Educator Resource Center Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec enjoyed breaking the rules. When Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec he came across an idea that interested him, he tried it—re- gardless of whether it was acceptable or not. Toulouse-Lautrec loved life and took inspiration from everything he came across. As a young man, he became interested in the circus and in Equestrienne (At the circus performers, and when a fellow artist showed him how to look at subjects as if they were cut off or “cropped” like a Circus Fernando) photograph, he took up that idea as well.1 Painted when he was only 24 years old, Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) 1887-1888 became one of his most well-known works. Oil on Canvas, 100.3 x 161.3 cm (39.5" x63.5") Toulouse-Lautrec: Childhood and Training As his name implies, Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse- Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1925.523 Lautrec-Montfa was born into a wealthy family on November 24, 1864. As a young child, his parents were aware that his physical development was not normal as he often was ill, his leg bones broke easily, his speech was unclear, and he didn’t grow taller as he aged. Discussing Toulouse-Lautrec’s condition in 1994, biographer Julia Frey calls it congenital (something he was essentially born with) and states, “Although posthumous diagnosis is always risky, experts on endocrine disorders say that Henry was probably suffering from a genetic mishap which caused fragility at the growth end of the bones, hindering normal bone development and causing pain, deformation and weakness in the skeletal structure.”2 She adds, “As he entered adolescence, Henry’s long bones began to atrophy at the joints where the adolescent growth spurt would typically manifest itself.”3 His cousins also showed such symptoms, making this a genetic defect within the family. -

A Bouquet of Five Art Movements a Crash Course in 19Th & 20Th Century Art Movements and Using Its Inspiration to Paint Flowers

A Bouquet Of Five Art Movements A crash course in 19th & 20th century art movements and using its inspiration to paint flowers. Did you know that according to Wikipedia there are over 180 art movements? For this week’s project we are going to spend time looking at just 5 of these movements and these were hugely influential during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They are: Day 1 - Impressionism Day 2 - Fauvism Day 3 - Cubism Day 4 - Abstract art Day 5 - Pop Art Day 6 challenge to create a picture for a Contactless Creativity group painting in the style of your preferred art movement Each day I will give you a little background information on the day’s art movement and its styles of painting. Then the task will be to create your own painting in the style of the art movement. The overall theme for the pictures is Flowers, however, if you have an alternative subject then you are very welcome to use that. At the end of the week the plan is for you to do a picture of a flower in your preferred art movement style and then pass it back to the Corn Exchange volunteer when they pick up your pack for it to be placed together to make a large piece of wonderful Contactless Creativity art work to be displayed somewhere at the Corn Exchange. A wonderful picture of loads of bright and colourful flowers will surely cheer us all up after lockdown! Materials For this week, I have provided you with simple materials: ❖ A couple of pencils and pencil sharpener ❖ A couple of paint brushes ❖ Tin of watercolours ❖ A4 sketchbook for you to keep. -

Fun Facts Outline-Bathers at Asnieres

Bathers at Asnieres By George-Pierre Seurat Print Facts • Medium: Oil on canvas • Date: 1884 • Size: 79” x 118” • Location: National Gallery, London • Style: Post-Impressionism, Mural painting • Genre: Genre Painting • Technique: Divisionism • Pronounced (az-nee-air) • Seurat was only 24 years old when he painted this painting and would only live 7 more years. • This was his first major painting. The Paris Salon rejected it. • This painting was highly criticized in its time as “too original” and was not regarded as a masterpiece until the 20th century. • The bathers are at the River Seine (pronounced Sen), just 5 miles from the center of Paris. • This painting is huge (79” x 118” or approximately 6.6 ft x 9.8 ft) • While the painting was not executed using Seurat's pointillist technique (pointillism), which he had not yet invented, the artist later reworked areas of this picture using dots of contrasting color to create a vibrant, luminous effect. For example, dots of orange and blue were added to the boy's hat. Artist Facts • Pronounced (sir-RAH) • Born December 2, 1859 • Seurat was born into a wealthy family in Paris, France. • Seurat died March 29, 1891 at the age of just 31. The cause of his death is unknown, but was possibly diphtheria. His one-year-old son died of the same disease two weeks later. • Seurat attended the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878 and 1879. • Chevreul, who developed the color wheel, taught Seurat that if you studied a color and then closed your eyes you would see the complementary color. -

Georges-Seurat-Artist-Fact-File.Pdf

Georges Seurat 1859 – 1891 Georges Pierre Seurat was born on 2nd December 1859 in Paris, France. His parents were wealthy and he had an older brother and sister. From an early age, Georges showed great artistic talent. He attended an art school called École Municipale de Sculpture et Dessin, and later École des Beaux-Arts where he learned about sculpture and drawing. He had to leave school to do a year of military training, but after this, he returned to the art world. He shared an apartment with his friend and spent much of his time mastering the art of monochrome drawing, which meant everything was in black and white. As Georges’ parents were wealthy, they helped him set up his own studio. He wasn’t a poor artist like many of his friends of that time. He developed a whole new technique to painting which became known as Pointillism. This is a style that describes the way in which paint is put on to canvas, tiny dots very close together, causing the human eye to blend the colours into an image when seen from a distance. He used the science of optics (the science of the eye) in this new style. Page 1 of 2 Georges Seurat In 1888, he painted one of his most famous paintings: Bathers in Asnières. It showed people relaxing by the River Seine. Georges was very proud of this work but it was rejected from the Paris Salon, the official French art exhibition. Instead he showed it to the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants, but soon wasn’t happy with how the group was organised. -

Georges Seurat Was and to Explore His Style of Art

Seurat and Pointillism Learning Objective: To find out who Georges Seurat was and to explore his style of art. www.planbee.com This man is called Georges Seurat. Over the next few lessons we are going to be finding out more about this famous artist and his style of art. What can you tell about this man from the photograph? www.planbee.com Georges Seurat was a French artist. He was born on 2nd December 1859 in Paris. His family was very rich. When he was a young man, he went to L’Ecole des Beaux Arts (the School of Fine Arts) where he developed his passion and talent for art. In France at that time, an art movement called Impressionism was Have a look at in full flow. Artists like Monet and the Renoir wanted to capture a fleeting Impressionist moment in time with their paintings. paintings on the They mostly painted outside and next slide. What wanted to capture the light. For this do you think of reason, they had to paint what they them? How saw quickly. When Impressionism would you was new, people thought that they describe this weren’t proper paintings and that style of art? they were just ‘impressions’. www.planbee.com This painting is called ‘Sunset on the Seine’ and is by Claude Monet. www.planbee.com This painting is called ‘Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette’ and is by Pierre- Auguste Renoir. www.planbee.com Impressionism became a very popular art movement. However, Seurat developed his own style of painting which was very different to the quick, light brushstrokes of Impressionism. -

Chapter 28 Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism: Europe and America, Y P 1870 to 1900 Selections From: Chapter 34 Japan

Chapter 28 Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Syypmbolism: Europe and America, 1870 to 1900 Selections from: Chapter 34 Japan, 1336 to 1980 3rd quarter of 19th century – 2nd Industrial Revolution. 1st – textiles, steam, iron 2nd – steel,,y,, electricity, chemicals, oil: foundation for plastics, machinery, building construction, and automobiles. Inventions of radio, electric light, telephone, and electric streetcar shortly followed. URBANIZATION – farmers with less land were squeezed from properties. Work opportunities in factories, improved health/living conditions in cities. MARXISM and DARWINISM 19th century empiricists, believed scientific, rational law governed nature. Marx –economic forces based on class struggl e iidnduced hihitstori cal change. Germans living in Paris, Marx and Engles wrote the communist Manifesto in 1848, advocating the creation of a socialist state – working class seized power and destroyed capitalism. Darwin challenged religious beliefs by postulating a competitive system where only fittest survive – contributed to growing secularism. SOCIAL DARWINISM: Herbert Spencer applied Darwinism to rapidly developing socioeconomic realm – justified colonization of less advanced peoples and cultures. By 1900 major economic and political powers divided up much of the world. French colonized N. Africa and Indochina; Br itish occu pied India, Australia, Nigeria, Egypt , Sudan, Rhodesia, Union of South Africa; Dutch were a majjpor presence in Pacific . MODERNISM: Darwin’s ideas of evolution, Marx’s emphasis on continuing sequence of conflicts – acute sense of world’s impermanence and constantlyygy shifting reality. Modernists transcend simple depiction of contemporary world (Realism), they examine premises of art itself (Manet in Le Dejejner l’Herbe). 20th century art critic Clement Greenberg wrote, “The limitations that constitute the medium of painting – the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment . -

Art-Georges-Seurat-Powerpoint.Pdf

Paris 1800s An Education in Art Georges Seurat was He studied art at the born in Paris on 2nd École Municipale de December 1859. He had Sculpture et Dessin. an older sister and an He finished his older brother. schooling in November 1879 and did a year of military service. Bathers at Asnières Seurat spent 1883 painting ‘Bathers at Asnières’. Seurat drew crayon pictures of models and made small oil sketches at the riverside to get an idea of how the light would affect his subjects. The Creation of Pointillism Georges Seurat created a whole new painting technique. He used the science of optics, and realised that if tiny dots of pure colour were painted close together, then the human eye would blend the dots to make a solid colour. Television screens work in Close up it is hard to see a the same way; clear image but when seen tiny pixels blend together to from a distance, a whole form a whole image of the subject painted image. can be seen. Harmony Seurat believed that a painter could use colour to create harmony in art like a musician uses melody and notes to create harmony. Seurat’s First Pointillist Painting Seurat’s first masterpiece where he displayed the pointillist technique was ‘A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte’. It took 2 years to paint and was completed in 1886. Click on the painting for a closer look. In the Woods at Pontaubert La Parade du Cirque The Seine at La Grande Jatte The Eiffel Tower At the End Georges Seurat died at the young age of 31 at his parents’ house on 29th March 1891.