Expressing Gestures and Emotions: Use of Lines in Georges Seurat's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

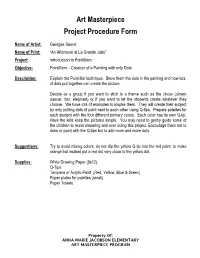

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form Name of Artist: Georges Seurat Name of Print: “An Afternoon at La Grande Jatte” Project: Introduction to Pointillism Objective: Pointillism – Creation of a Painting with only Dots Description: Exlplain the Pointillist technique. Show them the dots in the painting and how lots of dots put together can create the picture. Decide as a group if you want to stick to a theme such as the circus (clowm dancer, lion, elephant) or if you want to let the students create whatever they choose. We have lots of examples to inspire them. They will create their subject by only putting dots of paint next to each other using Q-tips. Prepare palettes for each student with the four different primary colors. Each color has its own Q-tip. Have the kids keep the pictures simple. You may need to gently guide some of the children to resist smearing and over doing this project. Encourage them not to draw or paint with the Q-tips but to add more and more dots. Suggestions: Try to avoid mixing colors, do not dip the yellow Q-tip into the red paint, to make orange but instead put a red dot very close to the yellow dot. Supplies: White Drawing Paper (9x12) Q-Tips Tempera or Acrylic Paint (Red, Yellow, Blue & Green) Paper plates for palettes (small) Paper Towels Property Of: ANNA MARIE JACOBSON ELEMENTARY ART MASTERPIECE PROGRAM Georges Seurat (Zhorzh Soo-Rah) Seurat was born in 1859 in Paris. He was the son of a comfortably situated middle class family. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

Degas: a New Vision and Seurat's Circus Sideshow

Michelle Foa exhibition review of Degas: A New Vision and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Citation: Michelle Foa, exhibition review of “Degas: A New Vision and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017), https://doi.org/ 10.29411/ncaw.2017.16.2.13. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Foa: Degas: A New Vision and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Degas: A New Vision Museum of Fine Arts, Houston October 16, 2016 – January 16, 2017 Previously at: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne June 24 – September 18, 2016 Seurat’s Circus Sideshow The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York February 17 – May 29, 2017 Catalogues: Degas: A New Vision. Henri Loyrette. Melbourne, Victoria: Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, 2016. 287 pp.; color illus.; bibliography; checklist. $35 ISBN: 9781925432114 Seurat’s Circus Sideshow. Richard Thomson, with contributions by Susan Alyson Stein, Charlotte Hale, and Silvia A. Centeno. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017. 144 pp.; 117 color illus.; bibliography; checklist; index. $30 ISBN: 9781588396150 Edgar Degas and Georges Seurat exhibited together only once, at the eighth and final Impressionist show in the spring of 1886. At that moment, Seurat was moving to the forefront of Paris’s modern art world, and A Sunday on the Grande Jatte–1884 (1884–86) would soon become a landmark in modern French painting. -

(At the Cirque Fernando) by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec

Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) 1887–1888 By Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO Department of Museum Education Division of Teacher Programs Crown Family Educator Resource Center Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec enjoyed breaking the rules. When Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec he came across an idea that interested him, he tried it—re- gardless of whether it was acceptable or not. Toulouse-Lautrec loved life and took inspiration from everything he came across. As a young man, he became interested in the circus and in Equestrienne (At the circus performers, and when a fellow artist showed him how to look at subjects as if they were cut off or “cropped” like a Circus Fernando) photograph, he took up that idea as well.1 Painted when he was only 24 years old, Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) 1887-1888 became one of his most well-known works. Oil on Canvas, 100.3 x 161.3 cm (39.5" x63.5") Toulouse-Lautrec: Childhood and Training As his name implies, Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse- Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1925.523 Lautrec-Montfa was born into a wealthy family on November 24, 1864. As a young child, his parents were aware that his physical development was not normal as he often was ill, his leg bones broke easily, his speech was unclear, and he didn’t grow taller as he aged. Discussing Toulouse-Lautrec’s condition in 1994, biographer Julia Frey calls it congenital (something he was essentially born with) and states, “Although posthumous diagnosis is always risky, experts on endocrine disorders say that Henry was probably suffering from a genetic mishap which caused fragility at the growth end of the bones, hindering normal bone development and causing pain, deformation and weakness in the skeletal structure.”2 She adds, “As he entered adolescence, Henry’s long bones began to atrophy at the joints where the adolescent growth spurt would typically manifest itself.”3 His cousins also showed such symptoms, making this a genetic defect within the family. -

Fun Facts Outline-Bathers at Asnieres

Bathers at Asnieres By George-Pierre Seurat Print Facts • Medium: Oil on canvas • Date: 1884 • Size: 79” x 118” • Location: National Gallery, London • Style: Post-Impressionism, Mural painting • Genre: Genre Painting • Technique: Divisionism • Pronounced (az-nee-air) • Seurat was only 24 years old when he painted this painting and would only live 7 more years. • This was his first major painting. The Paris Salon rejected it. • This painting was highly criticized in its time as “too original” and was not regarded as a masterpiece until the 20th century. • The bathers are at the River Seine (pronounced Sen), just 5 miles from the center of Paris. • This painting is huge (79” x 118” or approximately 6.6 ft x 9.8 ft) • While the painting was not executed using Seurat's pointillist technique (pointillism), which he had not yet invented, the artist later reworked areas of this picture using dots of contrasting color to create a vibrant, luminous effect. For example, dots of orange and blue were added to the boy's hat. Artist Facts • Pronounced (sir-RAH) • Born December 2, 1859 • Seurat was born into a wealthy family in Paris, France. • Seurat died March 29, 1891 at the age of just 31. The cause of his death is unknown, but was possibly diphtheria. His one-year-old son died of the same disease two weeks later. • Seurat attended the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878 and 1879. • Chevreul, who developed the color wheel, taught Seurat that if you studied a color and then closed your eyes you would see the complementary color. -

Georges-Seurat-Artist-Fact-File.Pdf

Georges Seurat 1859 – 1891 Georges Pierre Seurat was born on 2nd December 1859 in Paris, France. His parents were wealthy and he had an older brother and sister. From an early age, Georges showed great artistic talent. He attended an art school called École Municipale de Sculpture et Dessin, and later École des Beaux-Arts where he learned about sculpture and drawing. He had to leave school to do a year of military training, but after this, he returned to the art world. He shared an apartment with his friend and spent much of his time mastering the art of monochrome drawing, which meant everything was in black and white. As Georges’ parents were wealthy, they helped him set up his own studio. He wasn’t a poor artist like many of his friends of that time. He developed a whole new technique to painting which became known as Pointillism. This is a style that describes the way in which paint is put on to canvas, tiny dots very close together, causing the human eye to blend the colours into an image when seen from a distance. He used the science of optics (the science of the eye) in this new style. Page 1 of 2 Georges Seurat In 1888, he painted one of his most famous paintings: Bathers in Asnières. It showed people relaxing by the River Seine. Georges was very proud of this work but it was rejected from the Paris Salon, the official French art exhibition. Instead he showed it to the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants, but soon wasn’t happy with how the group was organised. -

Georges Seurat Was and to Explore His Style of Art

Seurat and Pointillism Learning Objective: To find out who Georges Seurat was and to explore his style of art. www.planbee.com This man is called Georges Seurat. Over the next few lessons we are going to be finding out more about this famous artist and his style of art. What can you tell about this man from the photograph? www.planbee.com Georges Seurat was a French artist. He was born on 2nd December 1859 in Paris. His family was very rich. When he was a young man, he went to L’Ecole des Beaux Arts (the School of Fine Arts) where he developed his passion and talent for art. In France at that time, an art movement called Impressionism was Have a look at in full flow. Artists like Monet and the Renoir wanted to capture a fleeting Impressionist moment in time with their paintings. paintings on the They mostly painted outside and next slide. What wanted to capture the light. For this do you think of reason, they had to paint what they them? How saw quickly. When Impressionism would you was new, people thought that they describe this weren’t proper paintings and that style of art? they were just ‘impressions’. www.planbee.com This painting is called ‘Sunset on the Seine’ and is by Claude Monet. www.planbee.com This painting is called ‘Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette’ and is by Pierre- Auguste Renoir. www.planbee.com Impressionism became a very popular art movement. However, Seurat developed his own style of painting which was very different to the quick, light brushstrokes of Impressionism. -

The Poetics of Parade and "Le Numéro Barbette"

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-2003 Cocteau au cirque: The Poetics of Parade and "Le Numéro Barbette" Jennifer Forrest Southwest Texas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Forrest, Jennifer (2003) "Cocteau au cirque: The Poetics of Parade and "Le Numéro Barbette" ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 27: Iss. 1, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1544 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cocteau au cirque: The Poetics of Parade and "Le Numéro Barbette" Abstract Parade (1917) was a joint effort production with libretto by Jean Cocteau music by Erik Satie, decor, costumes, and curtain by Pablo Picasso, and choreography by Léonide Massine. It was not only Cocteau's first truly original work, but, as Pierre Gobin contends, Parade is central to an understanding of the structures that would inform all of his subsequent work. Equally central, proposes Lydia Crowson, is Cocteau's July 1926 Nouvelle Revue Française article on "Le Numéro Barbette." The essay on the transvestite striptease trapezist Barbette offers a poetics of the theater that will have changed little by the time of his last play, L'Impromptu du Palais Royal. -

Seurat, Paintings and Drawings Edited by Daniel Catton Rich, with an Essay on Seurat's Drawings by Robert L

Seurat, paintings and drawings Edited by Daniel Catton Rich, with an essay on Seurat's drawings by Robert L. Herbert Author Art Institute of Chicago Date 1958 Publisher Art Institute of Chicago Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2792 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art Paintings and Drawings MoMA 629 c.2 LIBRARY Museumof ModernArt rchIve a ; — - PLEASERETUW TO 0! M0 n 11Qt WH ii SEURAT Paintings and Drawings EDITED BY DANIEL CATTON RICH WITH AN ESSAY ON SEURAT'S DRAWINGS BY ROBERT L. HERBERT The Art Institute of Chicago January 16 - March 7, 1958 The Museum of Modern Art, New York March 24 - May 11, 1958 PUBLISHEDBY THE ART INSTITUTEOF CHICAGO o /V\A 6 Frontispiece: 101 A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. The Art Institute of Chicago. Helen Birch Bartlett Collection On the cover: Detail from the above Trustees of The Art Institute of Chicago Everett D. Graff, President; Percy B. Eckhart, Senior Vice President; Leigh B. Block, Vice President; Arthur M. Wood, Vice President; George B. Young, Vice President; Homer J. Livingston, Treasurer; James W. Alsdorf, Lester Armour, Cushman B. Bissell, William McCormick Blair, Mrs. Leigh B. Block, Avery Brundage, Marshall Field, Jr., Frank B. Hubachek, Earle Ludgin, Samuel A. Marx, Brooks McCormick, Fowler McCormick, Andrew McNally III, Walter P. Paepcke, Daniel Catton Rich, Edward Byron Smith, Frank H. -

Seecstories.Com @Seecstories

George Seurat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDW4wSTm-V4 We learn how to combine colors to make pictures using just dots. Have your child use their creative side to make a picture by just using dots. Listen to your favorite music as inspiration for your picture. Art History and Artists Georges Seurat • Occupation: Artist, Painter • Born: December 2, 1859 in Paris, France • Died: March 29, 1891 (age 31) in Paris, France • Famous works: Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, Bathers at Asnières, The Circus • Style/Period: Pointillism, Neoimpressionist Biography: Where did Georges Seurat grow up? Georges Seurat grew up in Paris, France. His parents were wealthy allowing him to focus on his art. He was a quiet and intelligent child who kept to himself. Georges attended the School of Fine Arts in Paris starting in 1878. He also had to serve a year in the military. Upon his return to Paris he continued to refine his art skills. He spent the next two years drawing in black and white. Bathers at Asnieres With the help of his parents, Georges set up his own art studio not far from their house. Because his parents supported him, George was able to paint and explore any areas of art he chose. Most of the poor artists at the time had to sell their paintings to survive. Georges first major painting was Bathers at Asnieres. It was a large painting of people relaxing near the water at Asnieres. He was proud of the painting and submitted it to the official French art exhibition, the Salon. -

POST-IMPRESSIONISM (Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne) GEORGES SEURAT and PAUL CEZANNE

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: POST-IMPRESSIONISM (Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne) GEORGES SEURAT and PAUL CEZANNE: Online Links: Seurat's A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – Smarthistory Seurat's Bathers at Asnieres Georges Seurat and Neo-Impressionism -Hielbrumm Timeline of Art History Cezanne's Still Life with Apples Cezanne's Large Bathers – Smarthistory Bathers Not Beauties – ArtNews Young Woman Powdering Herself - The Guardian Georges Seurat. Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884-6 After his graduation from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Georges Seurat (1851-91) devoted his energies to “correcting” Impressionism, which he found too intellectually shallow and too improvisational. In the mid-1880s he gathered around him a circle of young artists who became known as the Neo-Impressionists. The work that became the centerpiece of the new movement and made his reputation was A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Art historians today use the term “Post-Impressionism” to refer to his work. Seurat took a typical Impressionist subject, weekend leisure activities, and gave it an entirely new handling. An avid reader of scientific color theory, he applied his paint in small dots of pure color, known as pointillism, in the belief that when they are “mixed” in the eye-as opposed to being mixed on the palette- the resulting colors would be more luminous. Seurat himself called this technique divisionism. Seurat’s divisionism was based on two relatively new theories of color. The first was that placing two colors side by side intensified the hues of each… The other theory, which is only partly confirmed by experience, asserted that the eye causes contiguous dots to merge into their combined color. -

Computing Lesson Two Pointillism

Computing lesson two Pointillism Can I explain what pointillism is? Can I use 2Paint a Picture to create my own art based upon this style? 1 Computing lesson two Pointillism A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat is two metres high and three metres long! 2 Computing lesson two Pointillism Pointillism was a development of impressionism. It was invented mainly by George Seurat and Paul Signac. Pointillist paintings are created by using small dots in different colours to build up the whole picture. Colours are placed near each other rather than mixed. Some pointillist pictures are huge and were all done by hand (not on a computer!). The different colours close together trick the eye into blurring all the dots into an overall image. The brain mixes the different colours together. See the dots that make up the man from Seurat's painting The Circus Pointillism used the science of optics to create colors from many small dots placed so close to each other that they would blur into an image to the eye. This is the same way computer screens work today. The pixels in the computer screen are just like the dots in a Pointillist painting. 3 Computing lesson two Pointillism 4 Computing lesson two Pointillism Remember to add water; this merges the dots together a bit. Experiment with the dot size by changing the slider at the bottom of the screen Remember to use the undo button! 5 Computing lesson two Pointillism Now we are going to paint a person or a portrait in a pointillism style.