Zones of the Oceans (Stations 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continental Shelf the Last Maritime Zone

Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone The Last Maritime Zone Published by UNEP/GRID-Arendal Copyright © 2009, UNEP/GRID-Arendal ISBN: 978-82-7701-059-5 Printed by Birkeland Trykkeri AS, Norway Disclaimer Any views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/GRID-Arendal or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this book do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authority, or deline- ation of its frontiers and boundaries, nor do they imply the validity of submissions. All information in this publication is derived from official material that is posted on the website of the UN Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), which acts as the Secretariat to the Com- mission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): www.un.org/ Depts/los/clcs_new/clcs_home.htm. UNEP/GRID-Arendal is an official UNEP centre located in Southern Norway. GRID-Arendal’s mission is to provide environmental informa- tion, communications and capacity building services for information management and assessment. The centre’s core focus is to facili- tate the free access and exchange of information to support decision making to secure a sustainable future. www.grida.no. Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Authors and contributors Tina Schoolmeester and Elaine Baker (Editors) Joan Fabres Øystein Halvorsen Øivind Lønne Jean-Nicolas Poussart Riccardo Pravettoni (Cartography) Morten Sørensen Kristina Thygesen Cover illustration Alex Mathers Language editor Harry Forster (Interrelate Grenoble) Special thanks to Yannick Beaudoin Janet Fernandez Skaalvik Lars Kullerud Harald Sund (Geocap AS) Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Foreword During the past decade, many coastal States have been engaged in peacefully establish- ing the limits of their maritime jurisdiction. -

Grade 3 Unit 2 Overview Open Ocean Habitats Introduction

G3 U2 OVR GRADE 3 UNIT 2 OVERVIEW Open Ocean Habitats Introduction The open ocean has always played a vital role in the culture, subsistence, and economic well-being of Hawai‘i’s inhabitants. The Hawaiian Islands lie in the Pacifi c Ocean, a body of water covering more than one-third of the Earth’s surface. In the following four lessons, students learn about open ocean habitats, from the ocean’s lighter surface to the darker bottom fl oor thousands of feet below the surface. Although organisms are scarce in the deep sea, there is a large diversity of organisms in addition to bottom fi sh such as polycheate worms, crustaceans, and bivalve mollusks. They come to realize that few things in the open ocean have adapted to cope with the increased pressure from the weight of the water column at that depth, in complete darkness and frigid temperatures. Students fi nd out, through instruction, presentations, and website research, that the vast open ocean is divided into zones. The pelagic zone consists of the open ocean habitat that begins at the edge of the continental shelf and extends from the surface to the ocean bottom. This zone is further sub-divided into the photic (sunlight) and disphotic (twilight) zones where most ocean organisms live. Below these two sub-zones is the aphotic (darkness) zone. In this unit, students learn about each of the ocean zones, and identify and note animals living in each zone. They also research and keep records of the evolutionary physical features and functions that animals they study have acquired to survive in harsh open ocean habitats. -

MARINE ENVIRONMENTS Teaching Module for Grades 6-12

MARINE ENVIRONMENTS Teaching Module for Grades 6-12 Dear Educator, We are pleased to present you with the first in a series of teaching and learning modules developed by the DEEPEND (Deep-Pelagic Nekton Dynamics) consortium and their consultants. DEEPEND is a research network focusing primarily on the pelagic zone of the Gulf of Mexico, therefore the majority of the lessons will be based around this topic. Whenever possible, the lessons will focus specifically on events of the Gulf of Mexico or work from the DEEPEND scientists. All modules in this series aim to engage students in grades 6 through 12 in STEM disciplines, while promoting student learning of the marine environment. We hope these lessons enable teachers to address student misconceptions and apprehensions regarding the unique organisms and properties of marine ecosystems. We intend for these modules to be a guide for teaching. Teachers are welcome to use the lessons in any order they wish, use just portions of lessons, and may modify the lessons as they wish. Furthermore, educators may share these lessons with other school districts and teachers; however, please do not receive monetary gain for lessons in any of the modules. Moreover, please provide credit to photographers and authors whenever possible. This first module focuses on the marine environment in general including biological, chemical, and physical properties of the water column. We have provided a variety of activities and extensions within this module such that lessons can easily be adapted for various grade and proficiency levels. Given that education reform strives to incorporate authentic science experiences, many of these lessons encourage exploration and experimentation to encourage students to think and act like a scientist. -

Lake Ecology

Fundamentals of Limnology Oxygen, Temperature and Lake Stratification Prereqs: Students should have reviewed the importance of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide in Aquatic Systems Students should have reviewed the video tape on the calibration and use of a YSI oxygen meter. Students should have a basic knowledge of pH and how to use a pH meter. Safety: This module includes field work in boats on Raystown Lake. On average, there is a death due to drowning on Raystown Lake every two years due to careless boating activities. You will very strongly decrease the risk of accident when you obey the following rules: 1. All participants in this field exercise will wear Coast Guard certified PFDs. (No exceptions for teachers or staff). 2. There is no "horseplay" allowed on boats. This includes throwing objects, splashing others, rocking boats, erratic operation of boats or unnecessary navigational detours. 3. Obey all boating regulations, especially, no wake zone markers 4. No swimming from boats 5. Keep all hands and sampling equipment inside of boats while the boats are moving. 6. Whenever possible, hold sampling equipment inside of the boats rather than over the water. We have no desire to donate sampling gear to the bottom of the lake. 7. The program director has final say as to what is and is not appropriate safety behavior. Failure to comply with the safety guidelines and the program director's requests will result in expulsion from the program and loss of Field Station privileges. I. Introduction to Aquatic Environments Water covers 75% of the Earth's surface. We divide that water into three types based on the salinity, the concentration of dissolved salts in the water. -

Environmental Science

LIVING THINGS AND THE ENVIRONMENT • Ecosystem: – All the living and nonliving things that ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE interact in a particular area – An organism obtains food, water, shelter, and other Populations and Communities things it needs to live, grow and reproduce from its surroundings – Ecosystems may contain many different habitats Science 7 Science 7 LIVING THINGS AND THE LIVING THINGS AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT • Habitat: • Biotic Factors: – The place and organism – The living parts of any lives and obtains all the ecosystem things it needs to survive – Example: Prairie Dogs – Example: • Hawks • Prairie Dog • Ferrets • Needs: • Badgers – Food • Eagles – Water • Grass – Shelter • Plants – Etc. Science 7 Science 7 LIVING THINGS AND THEIR LIVING THINGS AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT • Abiotic Factors: • Abiotic Factors con’t – Water: – Sunlight: • All living things • Necessary for require water for photosynthesis survival • Your body is 65% • Organisms which water use the sun form • A watermelon is the base of the 95% water food chain • Plants need water for photosynthesis for food and oxygen production Science 7 Science 7 1 LIVING THINGS AND THEIR LIVING THINGS AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT • Abiotic Factors Con’t • Abiotic Factors con’t – Oxygen: – Temperature: • Necessary for most • The temperature of living things an area determines • Used by animals the type of for cellular organisms which respiration can live there • Ex: Polar Bears do not live in the tropics • Ex: piranha’s don’t live in the arctic Science 7 Science -

HOLT Earth Science

HOLT Earth Science Directed Reading Name Class Date Skills Worksheet Directed Reading Section: What Is Earth Science? 1. For thousands of years, people have looked at the world and wondered what shaped it. 2. How did cultures throughout history attempt to explain events such as vol- cano eruptions, earthquakes, and eclipses? 3. How does modern science attempt to understand Earth and its changing landscape? THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF EARTH ______ 4. Scientists in China began keeping records of earthquakes as early as a. 200 BCE. b. 480 BCE. c. 780 BCE. d. 1780 BCE. ______ 5. What kind of catalog did the ancient Greeks compile? a. a catalog of rocks and minerals b. a catalog of stars in the universe c. a catalog of gods and goddesses d. a catalog of fashion ______ 6. What did the Maya track in ancient times? a. the tides b. the movement of people and animals c. changes in rocks and minerals d. the movements of the sun, moon, and planets ______ 7. Based on their observations, the Maya created a. jewelry. b. calendars. c. books. d. pyramids. Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved. Holt Earth Science 7 Introduction to Earth Science Name Class Date Directed Reading continued ______ 8. For a long time, scientific discoveries were limited to a. observations of phenomena that could be made with the help of scientific instruments. b. observations of phenomena that could not be seen, only imagined. c. myths and legends surrounding phenomena. d. observations of phenomena that could be seen with the unaided eye. -

Mapping the Canyon

Deep East 2001— Grades 9-12 Focus: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon Mapping the Canyon FOCUS Part III: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon ❒ Library Books GRADE LEVEL AUDIO/VISUAL EQUIPMENT 9 - 12 Overhead Projector FOCUS QUESTION TEACHING TIME What are the differences between bathymetric Two 45-minute periods maps and topographic maps? SEATING ARRANGEMENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES Cooperative groups of two to four Students will be able to compare and contrast a topographic map to a bathymetric map. MAXIMUM NUMBER OF STUDENTS 30 Students will investigate the various ways in which bathymetric maps are made. KEY WORDS Topography Students will learn how to interpret a bathymet- Bathymetry ric map. Map Multibeam sonar ADAPTATIONS FOR DEAF STUDENTS Canyon None required Contour lines SONAR MATERIALS Side-scan sonar Part I: GLORIA ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map trans- Echo sounder parency ❒ 1 local topographic map BACKGROUND INFORMATION ❒ 1 USGS Fact Sheet on Sea Floor Mapping A map is a flat representation of all or part of Earth’s surface drawn to a specific scale Part II: (Tarbuck & Lutgens, 1999). Topographic maps show elevation of landforms above sea level, ❒ 1 local topographic map per group and bathymetric maps show depths of land- ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map per group forms below sea level. The topographic eleva- ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map trans- tions and the bathymetric depths are shown parency ❒ with contour lines. A contour line is a line on a Contour Analysis Worksheet map representing a corresponding imaginary 59 Deep East 2001— Grades 9-12 Focus: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon line on the ground that has the same elevation sonar is the multibeam sonar. -

The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: a Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad

Environment and Natural Resources Research; Vol. 4, No. 1; 2014 ISSN 1927-0488 E-ISSN 1927-0496 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: A Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad Junior Darsan1 & Christopher Alexis2 1 University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad 2 Institute of Marine Affairs, Chaguaramas, Trinidad Correspondence: Junior Darsan, Department of Geography, University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 7, 2014 Accepted: February 7, 2014 Online Published: February 19, 2014 doi:10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 Abstract Coastal erosion threatens coastal land which is an invaluable limited resource to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Columbus Bay, located on the south-western peninsula of Trinidad, experiences high rates of coastal erosion which has resulted in the loss of millions of dollars to coconut estate owners. Owing to this, three makeshift sandbag groynes were installed in the northern region of Columbus Bay to arrest the coastal erosion problem. Beach profiles were conducted at eight stations from October 2009 to April 2011 to determine the change in beach widths and beach volumes along the bay. Beach width and volume changes were determined from the baseline in October 2009. Additionally, a generalized shoreline response model (GENESIS) was applied to Columbus Bay and simulated a 4 year model run. Results indicate that there was an increase in beach width and volume at five stations located within or adjacent to the groyne field. -

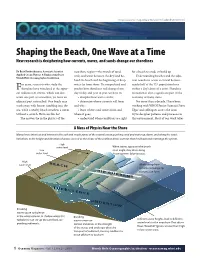

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

Lesson Plan – Ocean in Motion

Lesson Plan – Ocean in Motion Summary This lesson will introduce students to how the ocean is divided into different zones, the physical characteristics of these zones, and how water moves around the earths ocean basin. Students will also be introduced to organisms with adaptations to survive in various ocean zones. Content Area Physical Oceanography, Life Science Grade Level 5-8 Key Concept(s) • The ocean consists of different zones in much the same way terrestrial ecosystems are classified into different biomes. • Water moves and circulates throughout the ocean basins by means of surface currents, upwelling, and thermohaline circualtion. • Ocean zones have distinguishing physical characteristics and organisms/ animals have adaptations to survive in different ocean zones. Lesson Plan – Ocean in Motion Objectives Students will be able to: • Describe the different zones in the ocean based on features such as light, depth, and distance from shore. • Understand how water is moved around the ocean via surface currents and deep water circulation. • Explain how some organisms are adapted to survive in different zones of the ocean. Resources GCOOS Model Forecasts Various maps showing Gulf of Mexico surface current velocity (great teaching graphic also showing circulation and gyres in Gulf of Mexico), surface current forecasts, and wind driven current forecasts. http://gcoos.org/products/index.php/model-forecasts/ GCOOS Recent Observations Gulf of Mexico map with data points showing water temperature, currents, salinity and more! http://data.gcoos.org/fullView.php Lesson Plan – Ocean in Motion National Science Education Standard or Ocean Literacy Learning Goals Essential Principle Unifying Concepts and Processes Models are tentative schemes or structures that 2. -

A Database for Ocean Acidification Assessment in the Iberian Upwelling

Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 2647–2663, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-2647-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. ARIOS: a database for ocean acidification assessment in the Iberian upwelling system (1976–2018) Xosé Antonio Padin, Antón Velo, and Fiz F. Pérez Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas, IIM-CSIC, 36208 Vigo, Spain Correspondence: Xosé Antonio Padin ([email protected]) Received: 13 March 2020 – Discussion started: 24 April 2020 Revised: 21 August 2020 – Accepted: 30 August 2020 – Published: 4 November 2020 Abstract. A data product of 17 653 discrete samples from 3343 oceanographic stations combining measure- ments of pH, alkalinity and other biogeochemical parameters off the northwestern Iberian Peninsula from June 1976 to September 2018 is presented in this study. The oceanography cruises funded by 24 projects were primarily carried out in the Ría de Vigo coastal inlet but also in an area ranging from the Bay of Biscay to the Por- tuguese coast. The robust seasonal cycles and long-term trends were only calculated along a longitudinal section, gathering data from the coastal and oceanic zone of the Iberian upwelling system. The pH in the surface waters of these separated regions, which were highly variable due to intense photosynthesis and the remineralization of organic matter, showed an interannual acidification ranging from −0:0012 to −0:0039 yr−1 that grew towards the coastline. This result is obtained despite the buffering capacity increasing in the coastal waters further inland as shown by the increase in alkalinity by 1:1±0:7 and 2:6±1:0 µmol kg−1 yr−1 in the inner and outer Ría de Vigo respectively, driven by interannual changes in the surface salinity of 0:0193±0:0056 and 0:0426±0:016 psu yr−1 respectively. -

1 PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1

PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1, D.J.R. Walstra1,2 , C.S Swinkels1 In October and November 2009 a pilot project has been executed at the Delfland Coast in the Netherlands, constructing three small sandy headlands called Sand Groynes. Sand Groynes are nourished from the shore in seaward direction and anticipated to redistribute in the alongshore due to the impact of waves and currents to create the sediment buffer in the upper shoreface. The results presented in this paper intend to contribute to the assessment of Sand Groynes as a commonly applied nourishment method to maintain sandy coastlines. The morphological evolution of the Sand Groynes has been monitored by regularly conducting bathymetry surveys, resulting in a series of available bathymetry surveys. It is observed that the Sand Groynes have been redistributed in the alongshore, mainly in northward direction driven by dominant southwesterly wave conditions. Furthermore, data analysis suggests that Sand Groynes have a trapping capacity for alongshore supplied sand originating from upstream located Sand Groynes. A Delft3D numerical model has been set up to verify whether the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes can be properly hindcasted. Although the model has been set up in 2DH mode, hindcast results show good agreement with the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes based on field data. Trends of alongshore redistribution of Sand Groynes are well reproduced. Still the model performance could be improved, for instance by implementation of 3D velocity patterns and by a more accurate schematization of sediment characteristics. Keywords: Sand Groyne, Delfland Coast, sand nourishment, sediment transport, Delft3D INTRODUCTION Objective The main objective of this paper is to asses an innovative sand nourishment method to maintain a sandy coastline, by constructing small sandy headlands in the upper shoreface called Sand Groynes (see Figure 1).