Opendocpdf.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khatlon Flood Sitrep

Rapid Emergency Assessment & Coordination Team | Tajikistan REACT Floods in Kulyab City and Surrounding Districts, Khatlon Province GLIDE Number: FL-2010-000087-TJK Situation Report № 10 - 25 May 2010 Past reports and additional information can be found at http://www.untj.org/?c=7&id=318. Situation Overview On May 23, 2010 as a result of heavy rainfall and hailstorm Yovon and Norak districts of Khatlon Oblast have been affected. An 11 years old boy was killed by flooding. Many tents in the camps in Kulyab City has been flooded, all mattress and carpets within the tents got wet. Local authorities including government of Kulyab City together with CoES decided to evacuate families to the nearest school building in case of a long flooding. However, the rainfall lasted in a short period and there was no need in evacuation of the people. Damage and Needs Information Yovon District According to information received from CoES in Yovon District, the young boy (11 years old) named Emomali Boymurodov was killed by flooding. The boy was the citizen of Kumchi Village, Gulsara Yunusova Jamoat, Yovon District. Norak District The flooding of 23 May 2010 has affected over 50 houses and 35 heads of cattle within Puli Sangin and Dukoni jamoats of Norak District. Kulyab City Epidemiological situation of Charmgaron Street became a serious problem. The sewerage pipeline which was damaged by the flooding of 7 May 2010 is currently being rehabilitated by 12 specialists from municipal department of Kulyab City. However, there are 510 meters of pipeline damaged and the present resources are not enough to fix the line. -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

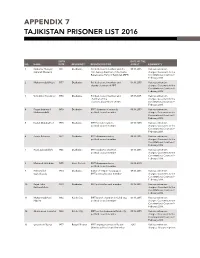

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

Pdf | 351.36 Kb

Rapid Emergency Assessment & Coordination Team | Tajikistan REACT Overview of Disasters in Tajikistan1 April– May 2014 Heavy rains triggered flash floods and mudslides in several districts of Tajikistan between April 11 to May 18, 2014. A reported total of 20 people died due to the floods. Significant damage was caused to households (damage to livelihoods and buildings), infrastructure and livestock. National and local authorities mobilized aid for the affected population with additional assistance from international humanitarian organizations. Details on losses and damage by location are provided below. Finalized damage assessments have not been completed for all locations and estimates of monetary losses are not currently available. Khatlon Province Shuroobod District, April 12-13, 2014: Heavy rains triggered flash floods and mudslide in Sarichashma Jamoat, Shuroobod District. A reported 111 households were affected, with 13 deaths. Significant damage was observed in local infrastructure with a reported 268 head of livestock killed, 188 hectares of productive land damaged and 5.5 kilometres of roads affected. Vose District, April 12-13, 2014: Heavy rains triggered flash floods in Tugarak Jamoat, Vose District. A reported 276 households were affected. Reports indicate that there was one death and a loss of 128 head of livestock. Reported damage to infrastructure include 2 kilometres of road and 78 hectares of agriculture land. Khamadoni District, April 12-13, 2014: Flash floods affected 70 households in Chubek Jamoat, Khamadoni District. One person was killed by the floods. The floods damage 115 hectares of agriculture land. More than 400 head of livestock were reported killed. A high school and policlinic and 5 kilometres of road were damaged. -

The Fault Lines of Violent Conflict in Tajikistan

The Fault Lines of Violent Conflict in Tajikistan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. August 2011 Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies (The Middle East and Central Asia) College of Arts and Social Sciences The Australian National University Christian Mark Bleuer 2 Declaration Except where otherwise acknowledged in the text, this thesis is based upon my own original research. The work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institute. _________________________ 12 August 2011 3 Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank my dissertation committee: Professor Amin Saikal, Dr. Kirill Nourzhanov and Dr. Robert L. Canfield. I am extremely grateful to have had the benefit of this high level of expertise on Central Asia while a PhD candidate at The Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies (The Middle East and Central Asia). Professor Saikal provided the firm guidance that kept me on track and reasonably on time with my work. His knowledge of Central Asian culture, history and politics was invaluable. Dr. Nourzhanov’s deep understanding of Tajikistan and Central Asia is what allowed me to produce this dissertation. He never failed to guide me towards the best sources, and the feedback he provided on my numerous drafts enabled me to vastly improve on the work that I had produced. I am also very grateful to Dr. Canfield who, despite being far away at Washington University in St. Louis, graciously agreed to be on my dissertation committee. His comments and criticism were valuable in refining my dissertation into the state that it is now in. -

Dropout Trend Analysis: Tajikistan

DROPOUT TREND ANALYSIS: TAJIKISTAN Contract No. EDH-I-00-05-00029-00 Task Order AID-OAA-TO-10-00010 August 2011 This study was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International. School Dropout Prevention Pilot Program Dropout Trend Analysis: Tajikistan Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development Washington, DC Submitted by: Creative Associates International, Inc. Washington, DC August, 2011 This report was made possible by the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Creative Associates International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. DEC Submission Requirements a. USAID Award Number Contract No. EDH-I-00-05-00029-00 Task Order AID-OAA-TO-10-00010 USAID Objective Title b. and Number Investing in People (IIP) USAID Project Title c. USAID Asia and Middle East Regional School Dropout and Number Prevention Pilot (SDPP) Program USAID Program Area d. Education (program area 3.2) and Program Element Basic Education (program element 3.2.1) e. Descriptive Title Dropout Trend Analysis for Tajikistan – School Dropout Prevention f. Author Name(s) Rajani Shrestha, Jennifer Shin, Karen Tietjen Creative Associates International, Inc. 5301 Wisconsin Avenue, NW, Suite 700 g. Contractor name Washington, DC 20015 Telephone: 202 966 5804 Fax: 202 363 4771 Contact: [email protected] Sponsoring USAID h. Operating Unit and AME/ME/TS COTR Rebecca Adams, COTR i. Date of Publication August, 2011 j. Language of Document English, Tajik, Russian Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures.......................................................................................................... -

Activity in Tajikistan

LIVELIHOODS άͲ͜ͲG ͞΄ͫΕ͟ ACTIVITY IN TAJIKISTAN A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) January 2011 LIVELIHOODS άͲ͜ͲG ͞΄ͫΕ͟ ACTIVITY IN TAJIKISTAN A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) January 2011 Α·͋ ̯Ϣχ·Ϊιν͛ ϭΊ͋Ϯν ͋ϳζι͋νν͇͋ ΊΣ χ·Ίν ζϢ̼ΜΊ̯̽χΊΪΣ ͇Ϊ ΣΪχ Σ͋̽͋νν̯ιΊΜϴ ι͕͋Μ͋̽χ χ·͋ ϭΊ͋Ϯν Ϊ͕ χ·͋ United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 1 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 3 National Livelihood Zone Map and Seasonal Calendar ................................................................................ 4 Livelihood Zone 1: Eastern Pamir Plateau Livestock Zone ............................................................................ 1 Livelihood Zone 2: Western Pamir Valley Migratory Work Zone ................................................................. 3 Livelihood Zone 3: Western Pamir Irrigated Agriculture Zone .................................................................... 5 Livelihood Zone 4: Rasht Valley Irrigated Potato Zone ................................................................................. 7 Livelihood Zone 5: Khatlon Mountain Agro-Pastoral Zone .......................................................................... -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Tajikistan: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Tajikistan: Floods DREF Operation Operation n° MDRTJ019 Glide n° FL-2014-000063-TJK Date of issue: 16 May 2014 Date of disaster: 11 May 2014 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact (name and title): Shamsudin Muhudinov Shuhrat Sangov Acting IFRC Representative for Tajikistan Director of DM Department Operation start date: 11 May 2014 Expected timeframe: May – August 2014 Overall operation budget: CHF 108,050 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 1,072 families (5,360 people) The total number of people to be assisted is 917 families (4,585 people): out of them 250 families (1,250 people) will be provided with non-food items. Hygiene promotion information materials and support in distributing clean drinking water will be provided to all 4,585 targeted residents. Host National Society presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): 24 Local Disaster Committee members and six staff of local branch supported by the RCST HQ Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation (if available and relevant): IFRC Representation in Tajikistan Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Government of Tajikistan and local authorities A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Heavy rainfall caused flooding and flash floods on 10 and 11 May 2014 in two provinces and two Direct Ruled District districts in Tajikistan. According to figures provided by the Committee of Emergency Situation and Civil Defense and the Red Crescent Society of Tajikistan, at least 1,072 families (5,360 people) have been severely affected by the floods1, and around 425 people, who lost their homes have been temporarily sheltered in kindergartens, mosques, at their relatives and in neighbouring villages. -

Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE (PGRFA) IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN COUNTRY REPORT BY PROF. DR. HAFIZ MUMINJANOV DUSHANBE 2008 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. -

Tajikistan Nhdr 2011.Pdf

U N D P NATIONAL HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2011 TAJIKISTAN: INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT Dushanbe-2012 Dear reader! With the initiative and support of UNDP and in cooperation with government ministries and agencies, civil society, international organizations working in Tajikistan, the analytical report under the title of 'National Human Development Report: Institutions and Development' has been developed, and brought to Your attention. It should be noted that development of human capacity and institutional capacity is considered one of the priority goals of the Government of the country, and this process is thoroughly reflected in the key socio-economic document of the country – the ”National Development Strategy of the Republic of Tajikistan for the period of 2015”. Therefore, special attention is paid to the development of human capacity and building and strengthening capacities in all areas of development of society. The current Report covers the issues of the role of institutions in the development process, with particular emphasis on the particular characteristics of this process. With regard to the analysis of development of human capacity in the country, the following topics have been thoroughly analyzed: the role of the state in the achievement of development goals, the legal framework for public administration, assessment of capacity for management of the development process, electronic government, partnership at the national level and etc. With a view to assessing institutional and human capacity, the concept of developing public policy on personnel, human resources management, and efficiency of personnel policy has also been analyzed. In parallel with that, in order to identify the role of self-government in the national development system, its role in the overall public administration system, the legal framework and reform, coordination of the implementation process for reform, partnership at the national level have been reviewed and examined. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for the Rehabilitation of Kizilkala–Bokhtar Section of Dushanbe–Bokhtar Road

THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR THE REHABILITATION OF KIZILKALA–BOKHTAR SECTION OF DUSHANBE–BOKHTAR ROAD FINAL REPORT February 2019 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. EI JR 19-014 THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR THE REHABILITATION OF KIZILKALA–BOKHTAR SECTION OF DUSHANBE–BOKHTAR ROAD FINAL REPORT February 2019 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the “Preparatory Survey for the Project for the Rehabilitation of Kizilkala-Bokhtar Section of Dushanbe– Bokhtar Road” and entrusted the survey to the CTI Engineering International Co., LTD. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Tajikistan, and conducted a field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Republic of Tajikistan for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. February, 2019 Itsu ADACHI Director General Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY 1. Situation of the Republic of Tajikistan Road network plays a vital role in the socio-economic growth of Tajikistan, as 92% of domestic freight and 98% of passenger transport rely on roads. It is an economic axis for domestic and international logistics. -

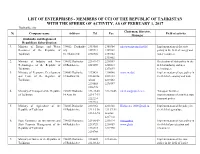

List of Enterprises

LIST OF ENTERPRISES - MEMBERS OF CCI OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN WITH THE SPHERE OF ACTIVITY, AS OF FEBRUARY 1, 2017 Dushanbe city Chairman, Director, № Company name Address Tel Fax Field of activity Manager Dushanbe and Regions of Republican Subordination 1. Ministry of Energy and Water 734012 Dushanbe 2353566 2360304 [email protected] Implementation of the state Resources of the Republic of city 2359914 2359802 policy in the field of energy and Tajikistan 5\1 Shamsi Str. 2360304 2359824 water resources 2359802 2. Ministry of Industry and New 734012 Dushanbe 221-69-97 2218889 Realization of state policy in the Technologies of the Republic of 22 Rudaki ave. 2215259 2218813 field of industry and new Tajikistan 2273697 technologies 3. Ministry of Economic Development 734002 Dushanbe 2273434 2214046 www.medt.tj Implementation of state policy in and Trade of the Republic of 37 Bokhtar Str. 2214623o 2215132 the field of economy and trade Tajikistan \about 2219463 2230668 2278597 2216778 4. Ministry of Transport of the Republic 734042 Dushanbe 221-20-03 221-20-03 [email protected]. Transport facilities, of Tajikistan 14 Ayni Str. 221-17-13 implementation of a unified state 2222214 transport policy 2222218 5. Ministry of Agriculture of the 734025 Dushanbe 2218264 2211628 [email protected] Implementation of the policy in Republic of Tajikistan 44 Rudaki Ave. 221-15-96 221-57-94 the field of agriculture 221-10-94 Isroilov 2217118 6. State Committee on Investments and 734025 Dushanbe 221-86-59 2211614 [email protected] Implementation of state policy in State Property Management of the 44 Rudaki Ave.