Download Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Aroma House, 55 Harlton Road, Little Eversden

Aroma House, 55 Harlton Road, Little Eversden Aroma House, 55 Harlton Road, Little Eversden, Cambridgeshire, CB23 1HD An extended Victorian house with delightful established gardens of just under half an acre, with potential development opportunity, in this small, highly regarded south west Cambridgeshire village. Cambridge 7 miles, Royston (fast train to King's Cross) 9 miles, M11 (junction 12) 5 miles, (distances are approximate). Gross internal floor area 1,945 sq.ft (181 sq.m) plus Studio Annexe 23'1 x 12'5 (7.04m x 3.78m) Ground Floor: Reception Hall, Cloakroom, Study, Sitting Room, Dining Room, Breakfast Room, Kitchen, Utility Room. First Floor: 4 Bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms (1 En Suite). Stonecross Trumpington High Street Outside: Off Street Parking, Workshop/Store, Wonderful Mature Gardens, Studio/Annexe with Sitting Cambridge Room, Shower Room and Mezzanine Sleeping Platform. CB2 9SU t: 01223 841842 In all about half an acre. e: [email protected] f: 01223 840721 bidwells.co.uk Please read Important Notice on the last page of text Particulars of Sale Situation Little Eversden is a small, attractive village Particular features of note include: - conveniently situated about 7 miles south west of Cambridge. There is a recreation ground with play Delightful dual aspect Sitting Room with Stylish Kitchen, re-fitted in 2007 with range of area for young children within close proximity, an glazed door to terrace, fireplace with inset matching base and wall cabinet's, granite work Italian restaurant within about half a mile and an wood burning stove and twin archways to surfaces and integrated Neff appliances Indian restaurant and village hall in the neighbouring adjoining Dining Room. -

Draft Recommendations for Cambridgeshire County Council

Contents Summary 1 1 Introduction 2 2 Analysis and draft recommendations 4 Submissions received 5 Electorate figures 5 Council size 5 Division patterns 6 Detailed divisions 7 Cambridge City 8 East Cambridgeshire District 13 Fenland District 16 Huntingdonshire District 19 South Cambridgeshire District 25 Conclusions 29 Parish electoral arrangements 29 3 Have your say 32 Appendices A Table A1: Draft recommendations for Cambridgeshire 34 County Council B Submissions received 39 C Glossary and abbreviations 41 Summary Who we are The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) is an independent body set up by Parliament. We are not part of government or any political party. We are accountable to Parliament through a committee of MPs chaired by the Speaker of the House of Commons. Our main role is to carry out electoral reviews of local authorities throughout England. Electoral review An electoral review examines and proposes new electoral arrangements for a local authority. A local authority’s electoral arrangements decide: How many councillors are needed How many wards or electoral divisions should there be, where are their boundaries and what should they be called How many councillors should represent each ward or division Why Cambridgeshire? We are conducting an electoral review of Cambridgeshire County Council as the Council currently has high levels of electoral inequality where some councillors represent many more or many fewer voters than others. This means that the value of each vote in county council elections varies depending on where you live in Cambridgeshire. Overall, 32% of divisions currently have a variance of greater than 10%. Our proposals for Cambridgeshire Cambridgeshire County Council currently has 69 councillors. -

Toni-Lynne Martin Family Tree

An Extract from the Holder Family Tree Compiled by Toni-Lynne Martin Mary 2 William HOLDER Elizabeth ETHERICK Born: Mar 1715 in St Giles Born: 1729 in London, England Cripplegate, England Bap: 19 Jul 1729 in St Giles, Bap: in Redmarley D'Abitot Cripplegate, London, England Bap: in Stroud, St Lawrence Died: c. 1756 in England Bap: 10 Mar 1715 in St Giles Buried: 10 Dec 1756 in St Giles, Cripplegate, London, London, Cripplegate, London, England England Bap: 10 Mar 1715 in St Giles, Cripplegate, London, England Bap: "Bet. 10 Mar 1715–1716" in St Giles, Cripplegate, London, England Died: c. 1771 in England Buried: 23 Dec 1771 in St Giles, Cripplegate, London, England William HOLDER Mary Ann JARMAN William HOLDER Martha HOLDER George HOLDER Sarah Simmons BONE a.k.a. William HOLDER Born: 1761 Born: 4 Aug 1755 in London, Born: 9 Mar 1758 in London, London, a.k.a. George Born: 6 Sep 1771 in St Botolph Born: 1751 in Meldreth, Bap: 25 Oct 1761 in Colne Engaine, England England Born: 7 Dec 1766 in London, Bishopsgate, London, England Cambridgeshire, England Essex, England Bap: 12 Aug 1755 in St Giles, Bap: 2 Apr 1758 in St. Sepulchre, England Bap: 25 Oct 1771 in St Botolph, Bap: 1751 in St Giles Cripplegate, Bap: 7 Nov 1762 in Saint Peters Cripplegate, London, England London, England Bap: 9 Dec 1766 in St Sepulchre, Bishopsgate, London, England London, London, England Thanet, Kent, England Died: Apr 1757 Died: Mar 1847 in Clapham, London, Holborn, London, England Marr: 20 Feb 1791 in St Botolph Died: 17 Sep 1813 in Meldreth, Bap: 15 Aug 1755 in Saint Andrew, Buried: 1 Apr 1757 in St Alban, Wood England Died: Aug 1829 in England without Bishopsgate, England Cambridgeshire, England Enfield, London, England Street, London, England Buried: 20 Mar 1847 in Holy Trinity, Buried: 21 Aug 1829 in London, Died: 1824 in England Buried: in Holy Trinity Church yard, Marr: 13 Dec 1781 in Meldreth, Clapham, England Middlesex, England Buried: 27 Feb 1824 in Birmingham, Meldreth, Cambridgeshire, Cambridgeshire, England St Mary, Warwickshire, England England. -

ECONOMY and ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE Date:Thursday, 14

ECONOMY AND ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE Date:Thursday, 14 March 2019 Democratic and Members' Services Fiona McMillan Monitoring Officer 10:00hr Shire Hall Castle Hill Cambridge CB3 0AP Kreis Viersen Room Shire Hall, Castle Hill, Cambridge, CB3 0AP AGENDA Open to Public and Press 1. Apologies for absence and declarations of interest Guidance on declaring interests is available at http://tinyurl.com/ccc-conduct-code 2. Minutes 7th February 2019 Economy and Environment Committee 5 - 18 3. Minute Action Log update 19 - 24 4. Petitions and Public Questions DECISIONS 5. East West Rail Company Consultation on Route Options between 25 - 54 Bedford and Cambridge 6. North East Cambridge Area Action Plan - Issues and Options 55 - 62 Consultation 2 Page 1 of 260 7. Land North West of Spittals Way and Ermine Street Great Stukeley 63 - 94 Outline Planning Application - Consultation Response 8. Kennett Garden Village Outline Planning Application - 95 - 110 Consultation response 9. Wellcome Trust Genome Campus Outline Planning Application 111 - 174 10. Connecting Cambridgeshire Programme Full Fibre Target 175 - 196 INFORMATION AND MONITORING 11. Finance and Performance Report to end of January 2019 197 - 240 12. Agenda Plan, Training Plan and Appointments to Outside Bodies, 241 - 260 Partnershp, Liaison, Advisory Groups and Council Champions 13. Date of Next Meeting 23rd May 2019 Subject to the April meeting being cancelled. The Economy and Environment Committee comprises the following members: Councillor Ian Bates (Chairman) Councillor Tim Wotherspoon (Vice-Chairman) -

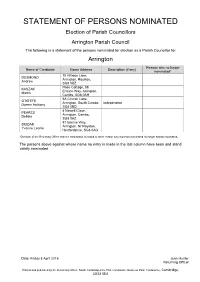

Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish Councillors Arrington Parish Council The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Arrington Reason why no longer Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) nominated* 10 Hillside Lane, DESMOND Arrington, Royston, Andrew SG8 0BZ Rose Cottage, 88 KASZAK Ermine Way, Arrington, Martin Cambs, SG8 0AH 9A Church Lane, O`KEEFE Arrington, South Cambs, Independent Darren Anthony SG8 0BD 4 Newell Close, PEARCE Arrington, Cambs, Debbie SG8 0AZ 51 Ermine Way, SIUDAK Arrington, Nr Royston, Yvonne Leonie Hertfordshire, SG8 0AG *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. Date: Friday 8 April 2016 Jean Hunter Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, South Cambridgeshire Hall, Cambourne Business Park, Cambourne, Cambridge, CB23 6EA STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish Councillors Cambourne Parish Council The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Cambourne Reason why no longer Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) nominated* 24 Foxhollow, Great CROCKER Cambourne, Cambridge, Simon Nicholas CB23 5HW 20 Brookfield Way, GAVIGAN Lower Cambourne, Patrick James Cambridgeshire, CB23 5ED 108 Greenhaze Lane, HUDSON Great Cambourne, Tom CB23 5BH 38, Lancaster Gate, MEHBOOB Upper Cambourne, Ghazala CB23 6AT 3 Langate Green, Great O`DWYER Cambourne, Cambridge, Joseph CB23 5AE 1 Whitley Road, Upper PATEL Cambourne, Jey Cambridgeshire, CB23 6AS 5, Chervil Way, Great POULTON Cambourne, Ruth Cambridgeshire, CB23 6BA SAWFORD 139 Jeavons Lane, Jeni Cambourne, CB23 5FA 14 Spar Close, Lower THOMPSON Cambourne, Greg Robert Cambridgeshire, CB23 6FG *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. -

Kingston Parish & Church Magazine

Kingston Parish & Church Magazine March 2017 Village Diary Wednesday 1st March Village Coffee/Tea – Village Hall – 10:30am Saturday 4th March Pub night – village hall, 6.00pm – 10.00pm Thursday 30th March Gesualdo Six Concert – details below Wheelie bin collection dates Wednesday 1st March Blue and Green bins Wednesday 8th March Black bin Wednesday 15 March Blue and Green Bins Wednesday 22nd March Black bin Wednesday 29th March Blue and Green Bins Please note: Wednesday is now our regular bin collection day. As before bins must be out by 6am at the latest on the collection day. Editorial We’re March-ing into spring! Snowdrops are blooming and daffodils are preparing to sprout. It won’t be long before we’ll see the kind of scene captured in David Heath’s cover photo. As the poet said, Oh! to be in Kingston now that spring is here! And it’s a busy month to come. It starts with a new bin day and then the excitement keeps mounting. On the same day, March 1st, the renewed coffee morning starts at 10.30 in the Village Hall, quickly followed by the Pub Night on March 4th (for further details see below). When you’ve recovered from those events, you’ll just have time to book your tickets for the Gesualdo Six concert on March 30th. Hurry because I hear that tickets are going fast. As I hoped would happen, there is a rich variety of offerings in this issue of the magazine, including major articles by Paul Custerson and David Heath. -

Diocese of Ely Directory

Diocese of Ely Directory Published: 12 February 2021 For comments, corrections or suggestions please email Jackie Williamson on [email protected] Introduction This directory has been ordered alphabetically by Archdeaconry > Deanery > Benefice - and then Church/Parish. For each Church/Parish, the names and contact details (email and telephone) have been included for the Licensed Clergy and Churchwardens. Where known a website and “A Church Near You” link have also been included. Towards the back of the directory, details have also been included that include, where known, the following contact details: • Rural Deans (name, number and email) • Clergy (name, number and email) • Clergy with Permission to Officiate (name, number and email) • General Synod Members from the Diocese of Ely - (name only) • Bishops Council (name only) • Diocesan Synod Members (Ely) (name only) • Assistant Bishops (name only) • Surrogates (name only) • Bishop’s and Archdeacons Office, Ely Diocesan Board of Finance staff, Cathedral Staff How to update or amend details If your details are inaccurate, or you would prefer a change to what is included, please direct your query as follows: • Licensed Clergy: Please contact the Bishop’s Office (https://www.elydiocese.org/about/contact-us/) • Clergy with PTO: Please contact the Bishop’s Office (https://www.elydiocese.org/about/contact-us/) • Churchwardens: Please contact the Archdeacon’s Office (https://www.elydiocese.org/about/contact-us/) • PCC Roles: [email protected] • Deanery/Benefice/Parish/Church names: DAC Office on [email protected] Data Protection The Ely Diocesan Board of Finance considers there to be a legitimate justification for publishing the contact details for Licensed Clergy (including those with PTO), Churchwardens and Diocesan staff (including those in the Archdeacons’ and Bishops’ offices) and key staff in Ely Cathedral in this Directory and on occasion the Diocesan website. -

The Elms, 23 High Street Little Eversden

THE ELMS, 23 HIGH STREET LITTLE EVERSDEN A spacious and contemporary, 4 bedroom house which enjoys delightful views overlooking open countryside, in this picturesque village 7 miles south west of Cambridge. Cambridge 7 miles, Comberton 3.5 miles, M11 (J12) 5 miles, Royston 9 miles with mainline railway station fast service to London King’s Cross in about 38 minutes. All distances and times are approximate. Property Summary Gross Internal Floor Area: 2,561 sq ft (238 sq m) • Ground Floor: Entrance Hall, Sitting Room, Study/Dining Room, Utility Room, Kitchen/Breakfast/Family Room, Cloakroom • First Floor: Principal Bedroom, Dressing Area, 3 Bedrooms, 3 Bath/Shower Rooms (2 En Suite) • Outside: Front and Rear Gardens, Double Garage with Studio, Off Street Parking for 2 Vehicles Please read Important Notice on the floor plan page THE ELMS, 23 HIGH STREET, LITTLE EVERSDEN, CAMBRIDGE CB23 1HE Description Built by local developer Juxta Properties in 2017, the property is constructed with attractive light brick elevations under a slate roof and has been built in a mock Victorian style. This superb detached family house enjoys southerly views to the front over open countryside and provides accommodation which has been designed with modern day living in mind, including a flexible layout and plenty of space for working and studying at home. Light and airy throughout, the property is in immaculate condition and provides prospective purchasers with a ready to move into option. Outside Sitting centrally within its plot, the property is set well back from the road with an area of lawn to the front bordered by pretty flower and shrub beds, and path leading to the front door. -

5 East West Rail Company Consultation on Route

Agenda Item No: 5 EAST WEST RAIL COMPANY CONSULTATION ON ROUTE OPTIONS BETWEEN BEDFORD AND CAMBRIDGE To: Economy and Environment Meeting Date: 14 March 2019 From: Graham Hughes, Executive Director, Place and Economy Electoral division(s): The five route options travel through Cambourne, Duxford, Gamlingay, St Neots East & Gransden, Hardwick, Melbourn & Bassingbourn, Papworth & Swavesey, Sawston & Shelford and Trumpington divisions Potential strategic implications across all divisions Forward Plan ref: Key decision: No Purpose: To consider the County Council’s response to the East West Rail company’s consultation Recommendation: Members are asked to: a) Confirm the Council’s strong support for the delivery of East West Rail central section b) Support Option A via Bedford South, Sandy and Bassingbourn as the Council’s preferred option c) Confirm that the Council agrees that the central section should enter Cambridge from the south d) Confirm the vital importance of the early delivery of Cambridge South station and four tracking between Cambridge Station and the Shepreth Branch junction e) Comment on and approve the appended draft response to the consultation f) Delegate to Executive Director Place and Economy in consultation with the Chairman of the Economy and Environment Committee, the authority to make minor changes to the response; and g) Confirm the Council’s strong support for the development and delivery of the East West Rail eastern section Officer contact: Member contact: Name: Jeremy Smith Name: Ian Bates Post: Group Manager, Transport Chairman: Economy and Environment Strategy and Funding Committee Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ov.uk Tel: 01223 715483 Tel: 01480 830250 1. -

Appendix 11: Matters Raised by the Public the Preferred Route Corridor

Appendix 11: Matters raised by the public The Preferred Route Corridor Theme Matter raised Regard had to the matter raised The Preferred Route Corridor A concern was raised that the route We recognise that some parts of each corridor takes in a significant number of route option will have pockets with en- existing settlements including Caxton, vironmental, infrastructure and housing The Preferred Bourn, Caldecote, Kingston, Toft and/ constraints. We will consider these factors Route Corridor or Comberton at the point where the as part of our work to select a preferred corridor is narrow, making avoidance route option, and further as we develop a difficult or impossible. preferred route alignment. A suggestion was made to consider Corridor N if Bedford Midland is ruled The Preferred Thank you for your suggestion. We have out on cost grounds, given that Corridor Route Corridor taken this into consideration. N would require less new railway than a route via Bedford. In their 2016 report “Partnering for Pros- perity”, the National Infrastructure Com- mission (NIC) suggested that “Maximising the potential of [the Oxford-Cambridge Expressway and East West Rail] to support well-connected and well-designed new communities will mean... developing the Comments were made suggestion that Oxford-Cambridge Expressway, along the The Preferred a broad corridor housing both the rail same broad corridor as East West Rail”. Route Corridor line and the new Expressway should be All five of our route options align with their considered. proposed approach. We will continue to work with Highways England to ensure that our respective pro- jects are designed and delivered in a way that best connects communities, takes account of environmental factors and sup- ports greater economic growth. -

Housing Need Survey Results Report for the Eversdens

Cambridgeshire ACRE Housing Need Survey Results Report for The Eversdens Survey undertaken in January 2014 Village sign © Copyright Keith Edkins and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence CONTENTS PAGE CONTEXT AND METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................3 Background to Affordable Rural Housing .................................................................................. 3 Context ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 3 The Eversdens ............................................................................................................................ 4 Local Income Levels and Affordability ....................................................................................... 5 RESULTS FROM PART ONE: VIEWS ON AFFORDABLE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT AND IDENTIFYING THOSE IN HOUSING NEED ........................................................................... 10 Views on Affordable Housing Development in The Eversdens ................................................ 10 Suitability of Current Home ..................................................................................................... 14 RESULTS FROM PART TWO: IDENTIFYING CIRCUMSTANCES AND REQUIREMENTS ........... 16 Local Connection to The Eversdens ........................................................................................ -

Landscapes Decoded 7/11/06 12:21 Pm Page I

landscapes decoded 7/11/06 12:21 pm Page i EXPLORATIONS IN LOCAL AND REGIONAL HISTORY Centre for English Local History, University of Leicester and Centre for Regional and Local History, University of Hertfordshire series editors: harold fox and nigel goose landscapes decoded 7/11/06 12:21 pm Page ii Also in this series Volume 2: The Self-Contained Village? The social history of rural communities, 1250–1900 edited by christopher dyer (ISBN 1-902806-59-X) landscapes decoded 7/11/06 12:21 pm Page iii LANDSCAPES DECODED The origins and development of Cambridgeshire’s medieval fields by susan oosthuizen university of hertfordshire press Explorations in Local and Regional History Volume 1 landscapes decoded 7/11/06 12:21 pm Page iv First published in Great Britain in 2006 by University of Hertfordshire Press Learning and Information Services University of Hertfordshire College Lane Hatfield Hertfordshire al10 9ab The right of Susan Oosthuizen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © Copyright 2006 Susan Oosthuizen All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1-902806-58-1 Design by Geoff Green Book Design, cb4 5ra Cover design by John Robertshaw, al5 2jb Printed in Great Britain by Alden Group Ltd, ox29 0yg Publication grant Publication has been made possible by a generous grant from the Aurelius Charitable Trust.