University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

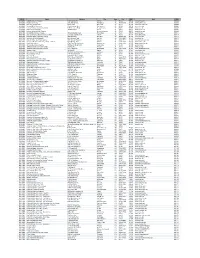

Office of Postsecondary Education Identifier Data

OPEID8 Name Address City State Zip IPED6 Web OPEID6 00100200 Alabama A & M University 4900 Meridian St Normal AL 35762 100654 www.aamu.edu/ 001002 00100300 Faulkner University 5345 Atlanta Hwy Montgomery AL 36109-3378 101189 www.faulkner.edu 001003 00100400 University of Montevallo Station 6001 Montevallo AL 35115 101709 www.montevallo.edu 001004 00100500 Alabama State University 915 S Jackson Street Montgomery AL 36104 100724 www.alasu.edu 001005 00100700 Central Alabama Community College 1675 Cherokee Road Alexander City AL 35010 100760 www.cacc.edu 001007 00100800 Athens State University 300 N Beaty St Athens AL 35611 100812 www.athens.edu 001008 00100900 Auburn University Main Campus Auburn University AL 36849 100858 www.auburn.edu 001009 00101200 Birmingham Southern College 900 Arkadelphia Road Birmingham AL 35254 100937 www.bsc.edu 001012 00101300 John C Calhoun State Community College 6250 U S Highway 31 N Tanner AL 35671 101514 www.calhoun.edu 001013 00101500 Enterprise State Community College 600 Plaza Drive Enterprise AL 36330-1300 101143 www.escc.edu 001015 00101600 University of North Alabama One Harrison Plaza Florence AL 35632-0001 101879 www.una.edu 001016 00101700 Gadsden State Community College 1001 George Wallace Dr Gadsden AL 35902-0227 101240 www.gadsdenstate.edu 001017 00101800 George C Wallace Community College - Dothan 1141 Wallace Drive Dothan AL 36303-9234 101286 www.wallace.edu 001018 00101900 Huntingdon College 1500 East Fairview Avenue Montgomery AL 36106-2148 101435 www.huntingdon.edu 001019 00102000 Jacksonville -

Amhs Plans Virtual Spring-Summer Programs

A Publication of the Abruzzo and Molise Heritage Society of the Washington DC Area May/June 2021 What’s Inside A documentary on celebrated chef and pasta expert Evan Funke (above) will be the subject of the next AMHS film discussion on June 12. Credit: Courtesy of Kitchen Detail 02 President’s Message 03 The Politically Talented AMHS PLANS VIRTUAL D’Alesandro Family, Part II 04 Author Michele Antonelli SPRING-SUMMER PROGRAMS Shares Wisdom from Abruzzo By Nancy DeSanti, 1st Vice President — Programs 05 Grab the Mattarello: ith the timetable for returning to in-person events still uncertain, the AMHS Program Let Battle Commence? Committee has lined up some interesting virtual events which we hope our members and friends will enjoy. 07 Campobasso’s Contributions W to Music and Film For May, we are planning to have a two-part program called “At the Table with Tony.” Tony Scilla is a relatively new AMHS member who will offer one program on the cuisine of Abruzzo and another on 08 Siamo Una Famiglia the cuisine of Molise. The events, to be held on separate Sunday afternoons, are being organized by Program Committee member Chris Renneker. Stay tuned for further details. 09 AMHS Membership Then on Saturday, June 12, at 8 p.m., we are pleased to offer a program based on the documentary “Funke” which profiles professional chef and pasta expert Evan Funke. Special guests will be the 10 Campo di Giove producer/director Gab Taraboulsy, and the producer/editor Alex Emanuele. The event, which will be in an interview format, is being organized by Program Committee member Lourdes Tinajero. -

Bus Regulations

BUS REGULATIONS PAYMENT The bus service is payable in full and in advance for the semester and regardless of the number of times the student(s) will utilize the service during the semester. Partial use of the bus service is not allowed, except under special circumstances approved by the Director of Operations. For organizational reasons, the only bus service options are ROUND TRIP; MORNING ONLY or AFTERNOON ONLY; LATE BUS ONLY 1 Only students for whom AOSR has a signed parental authorization form on file are permitted to ride the school bus. The form is requested for all students under the age of 14. STUDENT BEHAVIOR Students are expected to follow bus rules at all times when riding school buses. The following is a list of bus regulations. If these are not followed, the bus driver/monitor will report the offense to the bus coordinator. Parents will be notified of the offending behavior and students will be suspended from riding the bus, at first temporarily, and if necessary, permanently. ● Students must follow the directions of the bus driver/monitor in a respectful manner. ● All students are required to wear their seat belts. ● Only one student per seat and students must remain seated at all times. ● Students must not put their arms, hands, or heads out of the windows. ● Loud talking, swearing, rough play, or fighting is forbidden. ● Smoking is not allowed at any time. ● Riders must refrain from any action that would distract the driver and pose a safety problem for all on the bus. This includes gestures, making loud noises, the use of electronic devices, and inviting attention from pedestrians and motorists. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Manoscritti Tonini

Manoscritti Tonini strumento di corredo al fondo documentario a cura di Maria Cecilia Antoni Biblioteca Civica Gambalunga. Rimini. 2013 1 Il Fondo Tonini entrò in biblioteca nel 1924, in agosto una prima parte: più di 1500 fra volumi e opuscoli e dieci buste di manoscritti...e tutti i manoscritti, codici e pergamene appartenuti ai Tonini, custoditi dai fratelli Ricci,1 il resto in dicembre, in una stanza al piano terra di palazzo Gambalunga; il 26 aprile 1925 viene trasmessa al Sindaco di Rimini una Relazione degli esecutori testamentari: Alessandro Tosi e padre Gregorio Giovanardi2. La relazione, dattiloscritta, intitolata: Elenco manoscritti, opuscoli, libri di Luigi e Carlo Tonini, donati alla Biblioteca Gambalunga descrive nove nuclei contrassegnati da lettere alfabetiche (A-I) e da capoversi, interni ai nuclei, numerati progressivamente da 1 a 733; i nuclei A-F sono preceduti dal titolo: Luigi Tonini 4; il nucleo G è invece intitolato: Manoscritti di Carlo Tonini 5; seguono H: Pergamene (nn.47-53); I: Raccolta di documenti riguardanti la storia di Rimini ed altri luoghi, originali ed in copia. Questa descrizione tuttavia non permetteva più il rinvenimento dei documenti a causa di interventi, spostamenti e condizionamenti successivi6. 1 Articolo di G. GIOVANARDI, "La Riviera Romagnola", 11 settembre 1924, da cui è tratta la citazione sopra riportata. Nell'articolo Giovanardi individua dieci contenitori con lettere dell'alfabeto, da lui riordinati in questo modo: Busta A, Busta B, Busta C, contenenti le Vite d'insigni italiani di Carlo Tonini; Busta E con Epigrafi di Luigi e Carlo Tonini; Busta F Lavori di storia patri inediti di Luigi Tonini (tali Lavori sono numerati da I a XIV; i numeri XIII e XIV rimandano a volumi mss. -

TERRAIN VAGUE: the TIBER RIVER VALLEY Beatrice Bruscoli [email protected]

TERRAIN VAGUE: THE TIBER RIVER VALLEY Beatrice Bruscoli [email protected] Figure 1: Bridge on Via del Foro Italico looking downstream Rome, the Eternal City, continues to be Rome—to really begin to know the an active model and exemplary location city—we must walk through it, taking to study and understand the dynamic our time. Arriving at a gate in the transformations taking place in contem- Aurelian Wall, we cross the threshold porary landscapes. In the process of and enter the Campagna (countryside) becoming “eternal,” Rome has been that surrounds Rome just as it has for continually—often radically—altered, millenea. while conserving its primordial image; Looking through the multitude of renewing itself over time, without losing images, paintings, and plans of Rome, its deeply rooted structure. we cannot help but notice that its Before urban form, forma urbis, primary characteristics have remained there is natural form. As Christian distinct and constant over the centuries. Norberg-Schultz informs us, the genius Gianbattista Nolli’s “La Pianta Grande loci of Rome does not reside in some di Roma” of 1748 is the city’s most abstract geometric order or a formalized well-known representation.2 (Plan 1) architectural space, but in the close and This remarkable figure-ground map continuous ties between buildings, voids, presents us with a view of Rome; of a and the natural landscape.1 Rome’s dense compact area of inhabitation, forma urbis was generated and shaped dotted with piazzas and courtyards, and by the natural morphology of its land- surrounded with vast unbuilt areas all scape. -

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

HCS — History of Classical Scholarship

ISSN: 2632-4091 History of Classical Scholarship www.hcsjournal.org ISSUE 1 (2019) Dedication page for the Historiae by Herodotus, printed at Venice, 1494 The publication of this journal has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI Federico SANTANGELO (Venezia) (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) History of Classical Scholarship Issue () TABLE OF CONTENTS LORENZO CALVELLI, FEDERICO SANTANGELO A New Journal: Contents, Methods, Perspectives i–iv GERARD GONZÁLEZ GERMAIN Conrad Peutinger, Reader of Inscriptions: A Note on the Rediscovery of His Copy of the Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Rome, ) – GINETTE VAGENHEIM L’épitaphe comme exemplum virtutis dans les macrobies des Antichi eroi et huomini illustri de Pirro Ligorio ( c.–) – MASSIMILIANO DI FAZIO Gli Etruschi nella cultura popolare italiana del XIX secolo. Le indagini di Charles G. Leland – JUDITH P. HALLETT The Legacy of the Drunken Duchess: Grace Harriet Macurdy, Barbara McManus and Classics at Vassar College, – – LUCIANO CANFORA La lettera di Catilina: Norden, Marchesi, Syme – CHRISTOPHER STRAY The Glory and the Grandeur: John Clarke Stobart and the Defence of High Culture in a Democratic Age – ILSE HILBOLD Jules Marouzeau and L’Année philologique: The Genesis of a Reform in Classical Bibliography – BEN CARTLIDGE E.R. -

A Landscape with a Convoy on a Wooded Track Under Attack Oil on Panel 44 X 64 Cm (17⅜ X 25¼ In)

Sebastian Vrancx (Antwerp 1573 - Antwerp 1647) A Landscape with a Convoy on a Wooded Track under Attack oil on panel 44 x 64 cm (17⅜ x 25¼ in) Sebastian Vrancx was one of the first artists in the Netherlands to attempt battle scenes and A Landscape with Convoy on a Wooded Track under Attack offers an excellent example of his work. A wagon is under attack from bandits who have been hiding in the undergrowth on the right-hand side of the painting. The wagon has stopped as its driver flees for the safety of the bushes, whilst its occupants are left stranded inside. The wagon is guarded by three soldiers on horseback but in their startled state none have managed to engage their attackers. A line of bandits emerge from their hiding place and circle behind and around their victims, thus adding further to the confusion. Two figures remain in the bushes to provide covering fire and above them, perched in a tree, is one of their companions who has been keeping watch for the convoy and now helps to direct the attack. The scene is set in a softly coloured and brightly-lit landscape, which contrasts with the darker theme of the painting. Attack of Robbers, another scene of conflict, in the Hermitage, also possesses the decorative qualities and Vrancx’s typically poised figures, just as in A Landscape with a Convoy on a Wooded Track under Attack. A clear narrative, with travellers on horses attempting to ward off robbers, creates a personal and absorbing image. It once more reveals Vrancx’s delight in detailing his paintings with the dynamic qualities that make his compositions appealing on both an aesthetic and historical level. -

9781107013995 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01399-5 — Rome Rabun Taylor , Katherine Rinne , Spiro Kostof Index More Information INDEX abitato , 209 , 253 , 255 , 264 , 273 , 281 , 286 , 288 , cura(tor) aquarum (et Miniciae) , water 290 , 319 commission later merged with administration, ancient. See also Agrippa ; grain distribution authority, 40 , archives ; banishment and 47 , 97 , 113 , 115 , 116 – 17 , 124 . sequestration ; libraries ; maps ; See also Frontinus, Sextus Julius ; regions ( regiones ) ; taxes, tarif s, water supply ; aqueducts; etc. customs, and fees ; warehouses ; cura(tor) operum maximorum (commission of wharves monumental works), 162 Augustan reorganization of, 40 – 41 , cura(tor) riparum et alvei Tiberis (commission 47 – 48 of the Tiber), 51 censuses and public surveys, 19 , 24 , 82 , cura(tor) viarum (roads commission), 48 114 – 17 , 122 , 125 magistrates of the vici ( vicomagistri ), 48 , 91 codes, laws, and restrictions, 27 , 29 , 47 , Praetorian Prefect and Guard, 60 , 96 , 99 , 63 – 65 , 114 , 162 101 , 115 , 116 , 135 , 139 , 154 . See also against permanent theaters, 57 – 58 Castra Praetoria of burial, 37 , 117 – 20 , 128 , 154 , 187 urban prefect and prefecture, 76 , 116 , 124 , districts and boundaries, 41 , 45 , 49 , 135 , 139 , 163 , 166 , 171 67 – 69 , 116 , 128 . See also vigiles (i re brigade), 66 , 85 , 96 , 116 , pomerium ; regions ( regiones ) ; vici ; 122 , 124 Aurelian Wall ; Leonine Wall ; police and policing, 5 , 100 , 114 – 16 , 122 , wharves 144 , 171 grain, l our, or bread procurement and Severan reorganization of, 96 – 98 distribution, 27 , 89 , 96 – 100 , staf and minor oi cials, 48 , 91 , 116 , 126 , 175 , 215 102 , 115 , 117 , 124 , 166 , 171 , 177 , zones and zoning, 6 , 38 , 84 , 85 , 126 , 127 182 , 184 – 85 administration, medieval frumentationes , 46 , 97 charitable institutions, 158 , 169 , 179 – 87 , 191 , headquarters of administrative oi ces, 81 , 85 , 201 , 299 114 – 17 , 214 Church. -

Copyrighted Material

CHAPTER ONE i Archaeological Sources Maria Kneafsey Archaeology in the city of Rome, although complicated by the continuous occupation of the site, is blessed with a multiplicity of source material. Numerous buildings have remained above ground since antiquity, such as the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, temples and honorific arches, while exten- sive remains below street level have been excavated and left on display. Nearly 13 miles (19 kilometers) of city wall dating to the third century CE, and the arcades of several aqueducts are also still standing. The city appears in ancient texts, in thousands of references to streets, alleys, squares, fountains, groves, temples, shrines, gates, arches, public and private monuments and buildings, and other toponyms. Visual records of the city and its archaeology can be found in fragmentary ancient, medieval, and early modern paintings, in the maps, plans, drawings, and sketches made by architects and artists from the fourteenth century onwards, and in images captured by the early photographers of Rome. Textual references to the city are collected together and commented upon in topographical dictionaries, from Henri Jordan’s Topographie der Stadt Rom in Alterthum (1871–1907) and Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby’s Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1929), to Roberto Valentini and Giuseppe Zucchetti’s Codice Topografico della Città di Roma (1940–53), the new topographical dictionary published in 1992 by Lawrence RichardsonCOPYRIGHTED Jnr and the larger,MATERIAL more comprehensive Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae (LTUR) (1993–2000), edited by Margareta Steinby (see also LTURS). Key topographical texts include the fourth‐century CE Regionary Catalogues (the Notitia Dignitatum and A Companion to the City of Rome, First Edition. -

Pius Ix and the Change in Papal Authority in the Nineteenth Century

ABSTRACT ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Andrew Paul Dinovo This thesis examines papal authority in the nineteenth century in three sections. The first examines papal issues within the world at large, specifically those that focus on the role of the Church within the political state. The second section concentrates on the authority of Pius IX on the Italian peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. The third and final section of the thesis focuses on the inevitable loss of the Papal States within the context of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870. Select papal encyclicals from 1859 to 1871 and the official documents of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870 are examined in light of their relevance to the change in the nature of papal authority. Supplementing these changes is a variety of seminal secondary sources from noted papal scholars. Ultimately, this thesis reveals that this change in papal authority became a point of contention within the Church in the twentieth century. ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Andrew Paul Dinovo Miami University Oxford, OH 2004 Advisor____________________________________________ Dr. Sheldon Anderson Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. George Vascik Contents Section I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 Section II: Primary Sources……………………………………………………………….5 Section III: Historiography……...………………………………………………………...8 Section IV: Issues of Church and State: Boniface VIII and Unam Sanctam...…………..13 Section V: The Pope in Italy: Political Papal Encyclicals….……………………………20 Section IV: The Loss of the Papal States: The Vatican Council………………...………41 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..55 ii I.