An Edition of the Tragedie of Cleopatra, by Samuel Daniel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

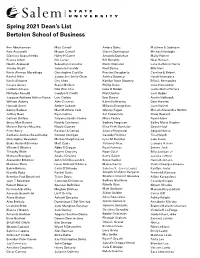

Spring 2021 Dean's List Bertolon School of Business

Spring 2021 Dean’s List Bertolon School of Business Ben Abrahamson Matt Carroll Ambra Doku Matthew S Gubitose Kyle Acciavatti Megan Carroll Gianni Dominguez Michael Hakioglu Gianluca Acquafredda Haley H Carter Amanda Donahue Molly Hamer Bianca Adam Nic Carter Bill Donalds Neal Hansen Noelle Alaboudi Sebastian Carvalho Daniel Donator Lana Kathleen Harris Jimmy Alcott Gabriela Cassidy Fiori Dorne Billy Hart Kevin Aleman Maradiaga Christopher Castillo Preston Dougherty Caroline E Hebert Rachel Allen Jacqueline Emily Chan Ashley Downey Handi Henriquez Kevin Almonte City Chen Katelyn Rose Downey Erika L Hernandez Cesare Aloise Stone M Chen Phillip Dube Julio Hernandez Luidwin Amaya Nok Wan Chu Luke D Dudek Leslie Maria Herrera Nicholas Ansaldi Carolyn R Cinelli Nick Dunfee Jack Hobbs Jayquan Anthony Arthur-Vance Lexi Ciolino Erin Dwyer Austin Holbrook William Aubrey Alex Cisneros Katie Eleftheriou Dom Hooven Hannah Aveni Amber Cokash Mikayla Evangelista Luan Horjeti Sonny Badwal Max Matthew Cole Wesley Fagan Miriam Alexandra Horton Jeffrey Baez Ryan Collins Art Fawehinmi Drew Howard Colleen Balfour Tatyana Conde-Correa Miles Feeley Ryan Huber Siena Mae Barone Nayely Contreras Sydney Ferguson Bailey Marie Hughes Melane Barrios-Macario Nicole Cooney Elise Firth-Gonzalez Geech Huot Peter Barry Rachael A Corrao Ariana Fitzgerald Abigail Hurley Zacharie Joshua Beauchamp Connor Corrigan Cassidy Fletcher Tina Huynh Christopher Beaudoin Michael Ralph Cosco Lynn M Fletcher Jake Irvine Blake Holland Benway Matt Coyle Yulianny Frias Leonora A Ivers Vikram S Bhamra Abby S Crogan Ryan Fuentes Steven Jack Timothy Blake Rupert Crossley Noor Galal Billy Jackson Jr Marissa Blonigen Anabel Cruzeta Kerry Galvin Jessica Jeffrey Alexander Bloomer John G D’Alessandro Steve Garber Hannah Jensen Madison Blum Louis Richard D’Amico Mateo Garcia Quelsi Georgia Jimenez Babin Bohara Carly D’Orlando Sabrina Y. -

De Nakomelingen Van Bernhard Wibben

een genealogieonline publicatie De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben door Cees Eekhout 5 augustus 2021 De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben Cees Eekhout De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben Generatie 1 1. Bernhard Wibben. Hij is getrouwd met Taleke. Zij kregen 1 kind: Hermann Wibben, volg 2. Bernhard is overleden. Generatie 2 2. Hermann Wibben, zoon van Bernhard Wibben en Taleke, is geboren rond 1645 in Wahn, Germany. Hij is getrouwd op 30 oktober 1666 in Sögel, Duitsland met Hempe Manings. Zij kregen 4 kinderen: Talle Wibben, volg 3. Bernhard Wibben, volg 4. Jan Wibben, volg 5. Hermann Wibben, volg 6. Hermann is overleden. Generatie 3 3. Talle Wibben, dochter van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 3 april 1667 in Wahn, Germany. Talle is overleden. 4. Bernhard Wibben, zoon van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 28 februari 1669 in Wahn, Germany. Bernhard is overleden. 5. Jan Wibben, zoon van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 26 oktober 1671 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. Hij is getrouwd met NN NN. Zij kregen 3 kinderen: Geerd Anton Wibben, volg 7. Enne Wibben, volg 8. Herman Wibben, volg 9. Jan is overleden op 37 jarige leeftijd op 13 september 1709 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. 6. Hermann Wibben, zoon van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 28 augustus 1679 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. Hermann is overleden. https://www.genealogieonline.nl/stamboom-cees-eekhout-en-cobie-pronk/ 1 De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben Cees Eekhout Generatie 4 7. Geerd Anton Wibben, zoon van Jan Wibben en NN NN, is geboren op 24 november 1700 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. -

Summer 2006 Shakespeare Matters Page 1

Summer 2006 Shakespeare Matters page 1 5:4 "Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments..." Summer 2006 “Stars or Suns:” The Portrayal of the Earls of Oxford in Elizabethan Drama By Richard Desper, PhD n Act III Scene vii of King Henry V, the proud nobles of France, gathered in camp on the eve of the battle of Agincourt, I speculate in anticipation of victory, letting their thoughts and their words take flight in fancy. While viewing the bedraggled English army as doomed, they savor their expected victory on the morrow and vie with each other in proclaiming their own glory. The dauphin1 boasts of his horse as another Pegasus, leading to a few allusions of a bawdy nature, and then a curious exchange takes place between Lord Rambures and the Constable of France, Professor William Leahy explains plans for a Shakespeare Charles Delabreth: Authorship Studies Master’s Program at Brunel University. Photo by William Boyle. Ram. My Lord Constable, the armor that I saw in your tent to-night, are those stars or suns upon it? Con. Stars, my lord. Brunel University to Offer 2 (Henry V, III.vii.63-5) Masters in Authorship Studies Shakespeare scholars have remarked little on these particular speeches, by default implying that they are words spoken in hile Concordia University has encouraged study of the passing, having no particular meaning other than idle chatter. Shakespeare authorship issue for years, Brunel One can count at least a dozen treatises on the text of Henry V that W University in England now plans to offer a graduate have nothing at all to say about these two lines.3 Yet numerous program leading to an M.A. -

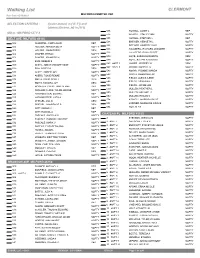

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021 SELECTION CRITERIA : ({voter.status} in ['A','I']) and {district.District_id} in [112] 535 HOWELL, JANET L REP MD-A - MILFORD CITY A 535 HOWELL, STACY LYNN NOPTY BELT AVE MILFORD 45150 535 HOWELL, STEPHEN L REP 538 BREWER, KENNETH L NOPTY 502 KLOEPPEL, CODY ALAN REP 538 BREWER, KIMBERLY KAY NOPTY 505 HOLSER, AMANDA BETH NOPTY 538 HALLBERG, RICHARD LEANDER NOPTY 505 HOLSER, JOHN PERRY DEM 538 HALLBERG, RYAN SCOTT NOPTY 506 SHAFER, ETHAN NOPTY 539 HOYE, SARAH ELIZABETH DEM 506 SHAFER, JENNIFER M NOPTY 539 HOYE, STEPHEN MICHAEL NOPTY 508 BUIS, DEBBIE S NOPTY 542 #APT 1 LANIER, JEFFREY W DEM 509 WHITE, JONATHAN MATTHEW NOPTY 542 #APT 3 MASON, ROBERT G NOPTY 510 ROA, JOYCE A DEM 543 AMAYA, YVONNE WANDA NOPTY 513 WHITE, AMBER JOY NOPTY 543 NORTH, DEBORAH FAY NOPTY 514 AKERS, TONIE RENAE NOPTY 546 FIELDS, ALEXIS ILENE NOPTY 518 SMITH, DAVID SCOTT DEM 546 FIELDS, DEBORAH J NOPTY 518 SMITH, TAMARA JOY DEM 546 FIELDS, JACOB LEE NOPTY 521 MCBEATH, COURTTANY ALENE REP 550 MULLEN, HEATHER L NOPTY 522 DUNHAM CLARK, WILMA LOUISE NOPTY 550 MULLEN, MICHAEL F NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, EDWIN L REP 550 MULLEN, REGAN N NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, JUDY A NOPTY 554 KIDWELL, MARISSA PAIGE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, JILL D DEM 554 LINDNER, MADELINE GRACE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, LAWRENCE B DEM 554 ROA, ALEX NOPTY 529 WITT, AARON C REP 529 WITT, RACHEL A REP CHATEAU PL MILFORD 45150 532 PASCALE, ANGELA W NOPTY 532 PASCALE, DOMINIC VINCENT NOPTY 2 STEVENS, JESSICA M NOPTY 532 PASCALE, MARK V NOPTY 2 #APT 1 CHURCHILL, REX -

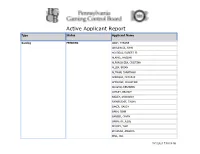

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

Tethys Festival As Royal Policy

‘The power of his commanding trident’: Tethys Festival as royal policy Anne Daye On 31 May 1610, Prince Henry sailed up the River Thames culminating in horse races and running at the ring on the from Richmond to Whitehall for his creation as Prince of banks of the Dee. Both elements were traditional and firmly Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester to be greeted historicised in their presentation. While the prince is unlikely by the Lord Mayor of London. A flotilla of little boats to have been present, the competitors must have been mem- escorted him, enjoying the sight of a floating pageant sent, as bers of the gentry and nobility. The creation ceremonies it were, from Neptune. Corinea, queen of Cornwall crowned themselves, including Tethys Festival, took place across with pearls and cockleshells, rode on a large whale while eight days in London. Having travelled by road to Richmond, Amphion, wreathed with seashells, father of music and the Henry made a triumphal entry into London along the Thames genius of Wales, sailed on a dolphin. To ensure their speeches for the official reception by the City of London. The cer- carried across the water in the hurly-burly of the day, ‘two emony of creation took place before the whole parliament of absolute actors’ were hired to play these tritons, namely John lords and commons, gathered in the Court of Requests, Rice and Richard Burbage1 . Following the ceremony of observed by ambassadors and foreign guests, the nobility of creation, in the masque Tethys Festival or The Queen’s England, Scotland and Ireland and the Lord Mayor of Lon- Wake, Queen Anne greeted Henry in the guise of Tethys, wife don with representatives of the guilds. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare, 36 | 2018 “The Dread of Something After Death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of S

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 36 | 2018 Shakespeare et la peur “The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of Shakespearean Revenants Christy Desmet Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4018 DOI: 10.4000/shakespeare.4018 ISSN: 2271-6424 Publisher Société Française Shakespeare Electronic reference Christy Desmet, ““The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of Shakespearean Revenants”, Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [Online], 36 | 2018, Online since 22 January 2018, connection on 25 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ shakespeare/4018 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare.4018 This text was automatically generated on 25 August 2021. © SFS “The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of S... 1 “The dread of something after death”: Hamlet and the Emotional Afterlife of Shakespearean Revenants Christy Desmet 1 Contemplating suicide, or more generally, the relative merits of existence and non- existence, Hamlet famously asks: Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country from whose bourn No traveler returns, puzzles the will And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of. (Hamlet, 3.1.84-90, emphasis added)1 Critics have complained that Hamlet knows right well what happens after death, as is made clear by the earlier account of his father, who is Doomed for a certain term to walk the night And for the day confined to fast in fires Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature Are burnt and purged away. -

R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons

R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons Karolina Alicja Trapp Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 The School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis engages with the poetry of R.S. Thomas. Surprisingly enough, although acclaim for Thomas as a major figure on the twentieth century’s literary scene has been growing perceptibly, academic scholarship has not as yet produced a full-scale study devoted specifically to the poetic character of Thomas’s writings. This thesis aims to fill that gap. Instead of mining the poetry for psychological, social, or political insights into Thomas himself, I take the verse itself as the main object of investigation. My concern is with the poetic text as an artefact. The main assumption here is that a literary work conveys its meaning not only via particular words and sentences, governed by the grammar of a given language, but also through additional artistic patterning. Creating a new set of multi-sided relations within the text, this “supercode” leads to semantic enrichment. Accordingly, my goal is to scrutinize a given poem’s artistic organization by analysing its component elements as they come together and function in a whole text. Interpretations of particular poems form the basis for conclusions about Thomas’s poetics more generally. Strategies governing his poetic expression are explored in relation to four types of experience which are prominent in his verse: the experience of faith, of the natural world, of another human being, and of art. -

Kalamazoo County Naturalization

Kalamazoo County Naturalization Last Name First Name Middle Name First Paper Second Paper Aach Rita Ann V66P5111 Aalbregtse Abraham Peter V10P163 Aalbregtse Johannes V12P446 Aalbregtse Jozias V11P151 Aalbregtse Suzanna Maria V58P3802 Aarssen Diederika Frederika Willemina V13P40 Abbate Santi V13P56 Abbate Santi V34P29 V34P29 Abolins Aina V64P4686 Abolins Augusts V64P4687 Abolins Guntis V64P4688 Abolins Mara V64P4627 Aboshin Aglou Ismail V29P64 V29P64 Abraham Francis T V10P219 Abraham Francis Thurlborn V23P104 V23P104 Abraham Maurice George V10P237 Abraham Thomas J V4P41 Abraham Thomas J V5P134 Abrahamse Pieter V3P262 Abromson Isral V5P314 Achterhof Albert V64P4603 Achterhof Johanna V59P3900 Adam Ben V52P3134 Adam Enke V14P204 Adam Simon V11P102 Adam Simon V14P213 Friday, July 06, 2007 Page 1 of 577 Kalamazoo County Naturalization Index Order copies of records by calling (517) 373-1408 Archives of Michigan Home page: www.michigan.gov/archivesofmi E-mail: [email protected] Last Name First Name Middle Name First Paper Second Paper Adam Simon V35P8 V35P8 Adamopooulos Fotis V34P39 V34P39 Adamopoulos Fotis V14P316 Adamopoulos James V30P27 Adams Aaltise V19P3868 Adams Antje V17P3172 Adams Claus John V51P3022 Adams Ella Nettie V71P27 Adams Enke V18P3596 Adams Frank V14P316 Adams Frank V34P39 V34P39 Adams Jacoba V57P3649 Adams James V30P27 Adams Kaert V46P2556 Adams Koert V46P2556 Adams Magdalena Anne V51P3034 Adams Nicky V58P3833 Adkin Marion Jean V53P3215 Adler Nathan V52P3189 Advocaat John Edward V21P4397 Aelick William John V23P142 V23P142 -

The Speaking Picture of the Mind: the Poetic Style of Samuel

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 The pS eaking Picture of the Mind: The oP etic Style of Samuel Daniel Harold Norbert Hild Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Hild, Harold Norbert, "The peS aking Picture of the Mind: The oeP tic Style of Samuel Daniel" (1974). Dissertations. Paper 1405. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1405 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Harold Norbert Hild p ''THE SPEAKING PICTURE OF THE MIND:" THE POETIC STYLE OF SAMUEL DANIEL by /' Harold N. Hild A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1974 r VITA The author, Harold Norbert Hild, is the son of Harold Joseph Hild and Franc;es (Wilson) Hild. He was born June 1, 1941, in Oak Park, Illinois. His elementary education was obtained in the public and parochial schools of Chicago, Illinois, and secondary education at Leo High School, Chicago, Illinois, where he was graduated in 1959. In September, 1959, he entered DePaul University, Chicago, and in June, 1964, received the degree of Bachelor of Arts with a major in English Literature and minors in philosophy and psychology. While attending DePaul University, he was president of Alpha Chi fraternity, president of the Inter-fraternity Council, president of the junior class. -

The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra

The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra William Shakespeare ***The Project Gutenberg's Etext of Shakespeare's First Folio*** ************The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra************* This is our 3rd edition of most of these plays. See the index. Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare July, 2000 [Etext #2268] ***The Project Gutenberg's Etext of Shakespeare's First Folio*** ************The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra************* *****This file should be named 0ws3510.txt or 0ws3510.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, 0ws3511.txt VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, 0ws3510a.txt Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. Therefore, we usually do NOT keep any of these books in compliance with any particular paper edition. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, leaving time for better editing. -

Contents. the Tragedy of Cleopatra by Samuel Daniel. Edited by Lucy Knight Editing a Renaissance Play Module Code: 14-7139-00S

Contents. The tragedy of Cleopatra By Samuel Daniel. Edited by Lucy Knight Editing a Renaissance Play Module Code: 14-7139-00S Submitted towards MA English Studies January 11th, 2011. 1 | P a g e The Tragedy of Cleopatra Front matter Aetas prima canat veneres, postrema tumultus.1 To the most noble Lady, the Lady Mary Countess of Pembroke.2 Behold the work which once thou didst impose3, Great sister of the Muses,4 glorious star5 Of female worth, who didst at first disclose Unto our times what noble powers there are In women’s hearts,6 and sent example far, 5 To call up others to like studious thoughts And me at first from out my low repose7 Didst raise to sing of state and tragic notes8, Whilst I contented with a humble song Made music to myself that pleased me best, 10 And only told of Delia9 and her wrong And praised her eyes, and plain’d10 mine own unrest, A text from whence [my]11 Muse had not digressed Had I not seen12 thy well graced Antony, Adorned by thy sweet style in our fair tongue 15 1 ‘Let first youth sing of Venus, last of civil strife’ (Propertius, 2.10.7). This quote is a reference to the Classical ‘Cursus,’ which state that you graduate from writing poetry to writing tragedy. Daniel is saying he wrote love poetry in his youth but now Mary Sidney has given him the courage to aspire to greater things, i.e. tragedy. 2 Mary Sidney. See Introduction, ‘Introductory dedication: Mary Sidney and family’.