Introduction, Eastman Continued to Grow Steadily, Entering New Overseas Markets and Expanding Existing Ones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Ex-Lexes' Cherished Time on Hawaiian Room's Stage POSTED: 01:30 A.M

http://www.staradvertiser.com/businesspremium/20120622__ExLexes_cherished_time_on_Hawaiian_Rooms_stage.html?id=159968985 'Ex-Lexes' cherished time on Hawaiian Room's stage POSTED: 01:30 a.m. HST, Jun 22, 2012 StarAdvertiser.com Last week, we looked at the Hawaiian Room at the Lexington Hotel in New York City, which opened 75 years ago this week in 1937. The room was lush with palm trees, bamboo, tapa, coconuts and even sported a periodic tropical rainstorm, said Greg Traynor, who visited with his family in 1940. The Hawaiian entertainers were the best in the world. The Hawaiian Room was so successful it created a wave of South Seas bars and restaurants that swept the country after World War II. In this column, we'll hear from some of the women who sang and danced there. They call themselves Ex-Lexes. courtesy Mona Joy Lum, Hula Preservation Society / 1957Some of the singers and dancers at the Hawaiian Room in the Lexington Hotel. The women relished the opportunity to "Singing at the Hawaiian Room was the high point of my life," perform on such a marquee stage. said soprano Mona Joy Lum. "I told my mother, if I could sing on a big stage in New York, I would be happy. And I got to do that." Lum said the Hawaiian Room was filled every night. "It could hold about 150 patrons. There were two shows a night and the club was open until 2 a.m. I worked an hour a day and was paid $150 a week (about $1,200 a week today). It was wonderful. -

Single-Use Duodenoscopes and Duodenoscopes with Disposable End Caps

REPORT ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGY Single-use duodenoscopes and duodenoscopes with disposable end caps Prepared by: ASGE TECHNOLOGY COMMITTEE Arvind J. Trindade, MD,1,* Andrew Copland, MD,2,* Amit Bhatt, MD,3 Juan Carlos Bucobo, MD, FASGE,4 Vinay Chandrasekhara, MD, FASGE,5 Kumar Krishnan, MD,6 Mansour A. Parsi, MD, MPH, FASGE,7 Nikhil Kumta, MD, MS,8 Ryan Law, DO,9 Rahul Pannala, MD, MPH, FASGE,10 Erik F. Rahimi, MD,11 Monica Saumoy, MD, MS,12 Guru Trikudanathan, MBBS,13 Julie Yang, MD, FASGE,14 David R. Lichtenstein, MD, FASGE, (Chair, Technology Committee)15 This document was reviewed and approved by the Governing Board of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Background and Aims: Multidrug-resistant infectious outbreaks associated with duodenoscopes have been documented internationally. Single-use duodenoscopes, disposable distal ends, or distal end cap sealants could eliminate or reduce exogenous patient-to-patient infection associated with ERCP. Methods: This document reviews technologies that have been developed to help reduce or eliminate exogenous infections because of duodenoscopes. Results: Four duodenoscopes with disposable end caps, 1 end sheath, and 2 disposable duodenoscopes are re- viewed in this document. The evidence regarding their efficacy in procedural success rates, reduction of duode- noscope bacterial contamination, clinical outcomes associated with these devices, safety, and the financial considerations are discussed. Conclusions: Several technologies discussed in this document are anticipated to eliminate or reduce exogenous infections during endoscopy requiring a duodenoscope. Although disposable duodenoscopes can eliminate exog- enous ERCP-related risk of infection, data regarding effectiveness are needed outside of expert centers. Addition- ally, with more widespread adoption of these new technologies, more data regarding functionality, medical economics, and environmental impact will accrue. -

“West Yard” at Terminal 91 for the Port of Seattle November 2, 2011

PHASE I ENVIRONMENTAL SITE ASSESSMENT PORT OF SEATTLE “WEST YARD” AT TERMINAL 91 FOR THE PORT OF SEATTLE NOVEMBER 2, 2011 PREPARED BY PINNACLE GEOSCIENCES, INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................. 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 2 2.1 Purpose ........................................................................................................ 2 2.2 Scope of Services .......................................................................................... 2 2.3 Significant Assumptions ................................................................................ 5 2.4 Limitations and Exceptions ........................................................................... 5 2.5 Special Terms and Conditions ....................................................................... 5 2.6 User Reliance ................................................................................................ 5 3.0 SITE AND VICINITY DESCRIPTION ........................................ 6 3.1 Location and Legal Description ..................................................................... 6 3.2 Site and Vicinity General Characteristics ....................................................... 6 3.3 Current Use of the Property .......................................................................... 6 3.4 Site Structures, Utilities, and Other Improvements ......................................... 6 3.5 Current Use of Adjoining -

The Image Processing Handbook, Third Edition by John C

The Image Processing Handbook, Third Edition by John C. Russ CRC Press, CRC Press LLC ISBN: 0849325323 Pub Date: 07/01/98 Search Tips Search this book: Advanced Search Introduction Acknowledgments Chapter 1—Acquiring Images Human reliance on images for information Using video cameras to acquire images Electronics and bandwidth limitations High resolution imaging Color imaging Digital cameras Color spaces Color displays Image types Range imaging Multiple images Stereoscopy Imaging requirements Chapter 2—Printing and Storage Printing Dots on paper Color printing Printing hardware Film recorders File storage Optical storage media Magnetic recording Databases for images Browsing and thumbnails Lossless coding Color palettes Lossy compression Other compression methods Digital movies Chapter 3—Correcting Imaging Defects Noisy images Neighborhood averaging Neighborhood ranking Other neighborhood noise reduction methods Maximum entropy Contrast expansion Nonuniform illumination Fitting a background function Rank leveling Color shading Nonplanar views Computer graphics Geometrical distortion Alignment Morphing Chapter 4—Image Enhancement Contrast manipulation Histogram equalization Laplacian Derivatives The Sobel and Kirsch operators Rank operations Texture Fractal analysis Implementation notes Image math Subtracting images Multiplication and division Chapter 5—Processing Images in Frequency Space Some necessary mathematical preliminaries What frequency space is all about The Fourier transform Fourier transforms of real functions Frequencies and -

Photofinishing Prices 08-01-19 X CUSTOMER 08-03-19.Pub

Miscellaneous Film Processing Services (Page 1 of 2) August 1, 2019 110 & 126 Develop, Scan & Print (C-41) Seattle Filmworks 35mm Processing Service Time: 10 Lab Days Matte or Glossy finish prints. Process: ECN-II or SFW-XL. Service Time: up to 2 weeks. C-41 process. Prints, if requested, on Kodak Royal paper. Applicable Films: Seattle Filmworks; Signature Color; Scanning the negatives is required prior to making prints. Eastman 5247 or 5294; Kodak Vision 2 or Vision 3 500T / We develop your cartridge of negatives ($4.90), scan the 5218 or 7218. visible images ($1.58 per negative), and, if requested, make prints ($0.20 per print). Scans are written to CD (no charge). Choose Matte or Glossy, 4x6 or 3½x5. Kodak Royal Paper. 110 film makes 4x5" prints. 126 film makes 4x4" prints. Default service is 4x6 Matte prints (if you don’t specify). Minimum charge : $12.00 Develop Only service Minimum Charge : $4.90 Develop Only service (blank film) ECN-II Develop & Print 4x6 or 3½x5 Identical 110 & 126 C-41 Develop Negatives & Scan to CD First Set 2nd Set Develop Develop & 20 or 24 Exposure ....................... 22.95 .................... 6.00 & Scan Scan & Print 36 Exposure ................................ 26.95 .................... 9.00 12 Exposure ................................ 23.86 .................. 26.26 Scan ECN-II process film to CD: 24 Exposure ................................ 42.82 .................. 47.62 Discount for unscannable negs ….1.58 each 1Reprint 2Enlargement Discount for prints not made from blank images ..........20 each Quality Quality Scanning Price per Roll CD CD Scans & Prints from Old 110 & 126 Negs with Develop & Print .......... -

Kodak Movie News; Vol. 3, No. 1; Jan

VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1955 lntroducing in HERE's a new program on TV Peepers ... a nd Jamie. He also has to his T whichyou willwant to see! Forwethink credit the first Alan Young Show, Operation you will not only delight in "Norb.y" as a Airlift, October Story, and others. Before show, but will also welcome the Iast-minute these TV successes, his unusual talent was news of photo products and developments apparent in Walt Disney's Pinocchio, Peter which the program will bring you-in full Pan, Snow White, and many other films. TV color, if you're equipped to receive it Dave Swift has a deft and sure tauch audi- or in regular black-and-white, as most ences recognize and appreciate. folks will see it. He thinks "Norby" will be the best thing "Norby" is Kodak's first venture jnto he has dorre. So do we. TV. For years we've sought the right ve- "Norby" hicle. Here's why we think you'll like the The story result : The play is named after its leading.character, "Norby" is created, directed, a:nd pro- Pearson Norby, who, in the first show, becomes duced by David Swift. There are two other vice-president in charge of smail loans of the current TV hits, born of his active and per- ceptive mind, you probably know. Mr. Every week on NBC-TV Your family will Iove the NORBY family! Evan Elliot, as Hank Norby, , , Joan Lorring, as Helen Norby . .. Susan Halloran, as Dianne . and David Wayne, as Pearson Norhy First National Bank of Pearl River. -

Bronica Sq-A-M.Pdf

Congratulations on your choice of the Zenza Bronica SQ-Am single lens reflex camera which has been developed to provide the user with high quality performance, simple handling convenience and extremely useful versatility plus automatic motorized film winding and shutter cocking operations suitable for the professional photographer. Although the Zenza Bronica SQ-Am has been designed exclusively for motorized operations, it has, also, been developed as a complete modular "system" camera possessing complete interchangeability with the interchangeable lenses and accessories developed for the SQ and SQ-A models, on which the SQ-Am is also based, and, therefore, provides the user with a very high degree of motorization in daily operations, in addition to automatic film winding and shutter cocking actions. Although instructions following are based on a standard combination consisting of the SQ-Am main body with Zenzanon-S 80mm lens, Film Back SQ 120 and WaistLevel Finder S, the choice of the lens, film back and finder is left to the discretion of the photographer, who should choose those items best suited to the type of assignments contemplated. To obtain best results from the Zenza Bronica SQ-Am, may we suggest that you read this instruction manual through carefully, before you even touch the camera, as your pleasure in using the camera will be even greater if you thoroughly familiarize yourself with its working parts before loading your first roll of film. CONTENTS Specifications of the ZENZA 17. Interchanging Finders ................................23 BRONICA SQ-Am ......................................... 2 18. Waist-Level Finder and Parts of the ZENZA BRONICA Interchanging Magnifiers ..................................23 19. -

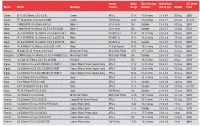

Sensor Zoom Min. Focusing Dimensions Est. Street Brand Model Mount(S) Format Range Distance (D X L) (In.) Weight Price

Sensor Zoom Min. Focusing Dimensions Est. Street Brand Model Mount(s) Format Range Distance (D x L) (in.) Weight Price Canon EF-S 18-200mm ƒ/3.5-5.6 IS Canon APS-C 11.1x 17.8 inches 3.1 x 6.4 20.9 oz. $699 Canon EF 28-300mm ƒ/3.5-5.6L IS USM Canon Full-Frame 10.7x 27.6 inches 3.6 x 7.2 59.2 oz. $2,449 Nikon 1 NIKKOR VR 10-100mm ƒ/4-5.6 Nikon 1 CX (1-inch) 10x Variable 2.4 x 2.8 10.5 oz. $549 Nikon 1 NIKKOR VR 10-100mm ƒ/4.5-5.6 PD-ZOOM Nikon 1 CX (1-inch) 10x Variable 3.0 x 3.7 18.2 oz. $749 Nikon AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-200mm ƒ/3.5-5.6G ED VR II Nikon DX (APS-C ) 11.1x 19.2 inches 3.0 x 3.8 19.8 oz. $649 Nikon AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-300mm ƒ/3.5-6.3G ED VR Nikon DX (APS-C) 16.7x 19.2 inches 3.0 x 3.8 19.4 oz. $699 Nikon AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-300mm ƒ/3.5-5.6G ED VR Nikon DX (APS-C) 16.7x Variable 3.3 x 4.7 29.3 oz. $999 Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 28-300mm ƒ/3.5-5.6G ED VR Nikon FX (Full-Frame) 10.7x 19.2 inches 3.3 x 4.5 28.2 oz. $949 Olympus M.Zuiko ED 14-150mm ƒ/4.0-5.6 II Micro Four Thirds Micro Four Thirds 10.7x 19.7 inches 2.5 x 3.3 10.0 oz. -

FILM FORMATS ------8 Mm Film Is a Motion Picture Film Format in Which the Filmstrip Is Eight Millimeters Wide

FILM FORMATS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 mm film is a motion picture film format in which the filmstrip is eight millimeters wide. It exists in two main versions: regular or standard 8 mm and Super 8. There are also two other varieties of Super 8 which require different cameras but which produce a final film with the same dimensions. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Standard 8 The standard 8 mm film format was developed by the Eastman Kodak company during the Great Depression and released on the market in 1932 to create a home movie format less expensive than 16 mm. The film spools actually contain a 16 mm film with twice as many perforations along each edge than normal 16 mm film, which is only exposed along half of its width. When the film reaches its end in the takeup spool, the camera is opened and the spools in the camera are flipped and swapped (the design of the spool hole ensures that this happens properly) and the same film is exposed along the side of the film left unexposed on the first loading. During processing, the film is split down the middle, resulting in two lengths of 8 mm film, each with a single row of perforations along one edge, so fitting four times as many frames in the same amount of 16 mm film. Because the spool was reversed after filming on one side to allow filming on the other side the format was sometime called Double 8. The framesize of 8 mm is 4,8 x 3,5 mm and 1 m film contains 264 pictures. -

Cognition: the Limit to Organization Change; a Case Study of Eastman Kodak

COGNITION: THE LIMIT TO ORGANIZATION CHANGE; A CASE STUDY OF EASTMAN KODAK A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Noah Simon April 2011 COGNITION: THE LIMIT TO ORGANIZATION CHANGE; A CASE STUDY OF EASTMAN KODAK Noah Simon April 2011 LAS: Leadership Abstract The following thesis examines an incumbent firm affected by change. It seeks to deepen the understanding of the dynamic capabilities model by proposing cognition and not previous resource deployment is the limit of change. Two similar companies, Eastman Kodak and Polaroid will be compared during the shift from film to digital photography to determine what separated the two companies. KEYWORDS: (Organizational cognition, dynamic capabilities, path dependency, cognition, perception) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 6 2.1 Dynamic Capabilities...................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 How does a company survive?.............................................................. 7 2.1.2 What are the effects of core competencies?.......................................... 8 2.1.3 How are established companies affected by change?........................... 9 2.2 The Cognitive Perspective.............................................................................. 10 2.2.1 What does a path dependency mean for the individual?....................... 10 2.2.2 What -

Film Capture for Digitization

2000 International Symposium on Silver2000 Halide International Technology Symposium on Silver Halide Technology Copyright 2000, IS&T Film Capture for Digitization Allan F. Sowinski, Lois A. Buitano, Steven G. Link, and Gary L. House Imaging Materials and Media, Research & Development Eastman Kodak Company Rochester, NY USA Abstract printing devices, including silver halide paper writers, inkjet printers, and thermal dye transfer printers, that will accept Digital minilab photofinishing is beginning to spread rapidly image data inputs from a variety of sources including digital in the market place, in part, as a means to provide access to still cameras, and film and paper scanners. When film network imaging services, and also to fulfill the printing scanning and digital writing have supplemented traditional needs of the growing base of consumer digital still cameras. optical photofinishing sufficiently, image-taking films When film scanning and digital writing have supplemented designed for optimal scan printing will be feasible. traditional optical photofinishing sufficiently, image-taking Design opportunities to improve silver halide image films designed for optimal scan-printing will be feasible. capture may be afforded as a result of these photofinishing Representative film digitization schemes are surveyed technology changes. Some features of silver halide capture in order to determine some of the optimal features of input may merit improvement or alteration in order for it to silver halide capture media. Key historical features of films remain a very attractive consumer and professional imaging designed for optical printing are considered with respect to technology. In addition, electronic image processing may this new image-printing paradigm. One example of an allow new chemical or emulsion technologies in film system enabled new film feature is recording the scene with design that were difficult to manage with the strict increased color accuracy through theoretically possible requirements of trade optical printing compatibility. -

CODE by R.Mutt

CODE by R.Mutt dcraw.c 1. /* 2. dcraw.c -- Dave Coffin's raw photo decoder 3. Copyright 1997-2018 by Dave Coffin, dcoffin a cybercom o net 4. 5. This is a command-line ANSI C program to convert raw photos from 6. any digital camera on any computer running any operating system. 7. 8. No license is required to download and use dcraw.c. However, 9. to lawfully redistribute dcraw, you must either (a) offer, at 10. no extra charge, full source code* for all executable files 11. containing RESTRICTED functions, (b) distribute this code under 12. the GPL Version 2 or later, (c) remove all RESTRICTED functions, 13. re-implement them, or copy them from an earlier, unrestricted 14. Revision of dcraw.c, or (d) purchase a license from the author. 15. 16. The functions that process Foveon images have been RESTRICTED 17. since Revision 1.237. All other code remains free for all uses. 18. 19. *If you have not modified dcraw.c in any way, a link to my 20. homepage qualifies as "full source code". 21. 22. $Revision: 1.478 $ 23. $Date: 2018/06/01 20:36:25 $ 24. */ 25. 26. #define DCRAW_VERSION "9.28" 27. 28. #ifndef _GNU_SOURCE 29. #define _GNU_SOURCE 30. #endif 31. #define _USE_MATH_DEFINES 32. #include <ctype.h> 33. #include <errno.h> 34. #include <fcntl.h> 35. #include <float.h> 36. #include <limits.h> 37. #include <math.h> 38. #include <setjmp.h> 39. #include <stdio.h> 40. #include <stdlib.h> 41. #include <string.h> 42. #include <time.h> 43. #include <sys/types.h> 44.