Farewell to the Kodak DCS Dslrs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nikon F3 Instruction Manual

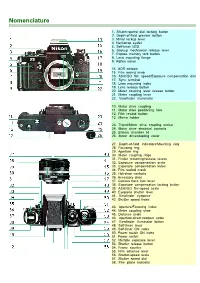

Nomenclature 1. Shutter-speed dial locking button 2. Depth-of-field preview button 3. Mirror lockup lever 4. Neckstrap eyelet 5. Self-timer LED 6. Backup mechanical release lever 7. Expose memory lock button 8. Lens mounting flange 9. Reflex mirror 14. ADR window 15. Film rewind knob 16. ASA/ISO film speed/Exposure compensation dial 17. Sync terminal 18. Lens mounting index 19. Lens release button 20. Meter coupling lever release button 21. Meter coupling lever 22. Viewfinder illuminator 10. Motor drive coupling 11. Motor drive positioning hole 12. Film rewind button 13. Memo holder 23. Tripod/Motor drive coupling socket 24. Motor drive electrical contacts 25. Battery chamber lid 26. Motor drivecoupling cover 27. Depth-of-field indicators/Mounting ring 28. Focusing ring 29. Aperture ring 30. Meter coupling ridge 31. Finder mounting/release levers 32. Exposure compensation scale 33. Exposure compensation index 34. Film rewind crank 35. Hot-shoe contacts 36. Accessory shoe 37. Camera back lock lever 38. Exposure compensation locking button 39. ASA/ISO film-speed scale 40. Eyepiece shutter lever 41. Viewfinder eyepiece 42. Shutter speed index 43. Aperture/Focusing index 44. Meter coupling shoe 45. Distance scale 46. Aperture-direct-readout scale 47. Viewfinder illuminator button 48. Self-timer lever 49. Self-timer ON index 50. Power switch ON index 51. Power switch 52. Multiple exposure lever 53. Shutter release button 54. Frame counter 55. Film advance lever 56. Shutter-speed scale 57. Shutter speed dial 58. Film plane indicator TABLE OF -

Page 16 of 128 Exhibit No. Description Deposition

Case 1:04-cv-01373-KAJ Document 467-2 Filed 10/23/2006 Page 1 of 140 Exhibit Description Deposition Objections No. Ex. No. PTX-168 7/16/2003, Technical Reference Napoli Ex. Manual [DM270] (EKCCCI007053- 132 836) PTX-169 2003, Data Sheet for TMS320DM270 Processor (AX200153-55) PTX-170 10/30/2002, DM270 Preliminary Napoli Ex. Register Manual Rev. b0.6 131 (EKCCCI001305-495) PTX-171 TI DM270 Imx Hardware Akiyama Programming Interface, Version 0.0 Ex. 312 (EKCNYII005007249-260) PTX-172 3/3/2003, DM270 Preliminary Data Ohtake Ex. Sheet Rev. b0.7C (EKCCCI008094- 123 131) PTX-173 Fact Sheet for TMS320DM270 Lacks Processor (AX200150-52) authenticity; Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-174 6/04, Data Sheet rev 0.5 for Hynix Ligler Ex. Lacks HY57V561620C[L]T[P] (AX200163- 13 (ITC) authenticity; 74) Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-175 Sharp RJ21T3AA0PT Data Sheet Hearsay; (EKCCCI017389-413) Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-176 DX7630 Thumbnail Test Lacks (AXD022568-81) authenticity; Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance; Inaccurate/ incomplete description PTX-177 1/11/2005, DM270 IP Chain ver. 0.7 Yoshikawa with translation (EKC001021025-31, Ex. 348 AX211033-42) PTX-178 1/26/2004, Bud Camera F/W Task Lacks foundation; Interface Capture Main <-> Image ISR Lacks relevance (DX7630) ver. 0.07 / Takeshi Domen with translation (EKCCCI002404-19, AX211607-26) Page 16 of 128 Case 1:04-cv-01373-KAJ Document 467-2 Filed 10/23/2006 Page 2 of 140 Exhibit Description Deposition Objections No. Ex. No. PTX-179 2/17/2003, Budweiser Camera EXIF Akiyama Lacks foundation; File Access Library Spec (DX7630) Ex. -

The Image Processing Handbook, Third Edition by John C

The Image Processing Handbook, Third Edition by John C. Russ CRC Press, CRC Press LLC ISBN: 0849325323 Pub Date: 07/01/98 Search Tips Search this book: Advanced Search Introduction Acknowledgments Chapter 1—Acquiring Images Human reliance on images for information Using video cameras to acquire images Electronics and bandwidth limitations High resolution imaging Color imaging Digital cameras Color spaces Color displays Image types Range imaging Multiple images Stereoscopy Imaging requirements Chapter 2—Printing and Storage Printing Dots on paper Color printing Printing hardware Film recorders File storage Optical storage media Magnetic recording Databases for images Browsing and thumbnails Lossless coding Color palettes Lossy compression Other compression methods Digital movies Chapter 3—Correcting Imaging Defects Noisy images Neighborhood averaging Neighborhood ranking Other neighborhood noise reduction methods Maximum entropy Contrast expansion Nonuniform illumination Fitting a background function Rank leveling Color shading Nonplanar views Computer graphics Geometrical distortion Alignment Morphing Chapter 4—Image Enhancement Contrast manipulation Histogram equalization Laplacian Derivatives The Sobel and Kirsch operators Rank operations Texture Fractal analysis Implementation notes Image math Subtracting images Multiplication and division Chapter 5—Processing Images in Frequency Space Some necessary mathematical preliminaries What frequency space is all about The Fourier transform Fourier transforms of real functions Frequencies and -

Are You Ready for a Digital Camera? by Jennifer Ruisaard and Conrad Turner

Are You Ready for a Digital Camera? by Jennifer Ruisaard and Conrad Turner Digital cameras flashed onto the technology scene a few years ago, threatening the future of conventional photography. Employing the same elements as traditional cameras, digital cameras convert images into a series of pixels that computers can understand and display directly on-screen. These digital images transmit easily through e-mail attachments and are instantly ready to use. The quality of digital images improved drastically over the last five years. In addition, digital cameras offer the benefits of speed, flexibility, and cost savings. Digital photographs are easy to retouch and manipulate through programs such as Photoshop. Furthermore, digital images do not need to be scanned. Therefore, defects introduced by the scanning process are eliminated. Types of Digital Cameras The digital photography market offers consumers three types of cameras: low-, mid-, and high-range. Buyers of digital cameras should choose a camera depending on their specific needs and the type of job to be done. Low-end digital cameras cost around $1,000 and are equivalent to conventional point-and- shoot cameras. Their low resolution, usually about 640 ´ 480 pixels, makes them a cost-effective tool for jobs that do not require high quality, sharpness, or color accuracy. This range of cameras can produce quality prints up to 2.4 ´ 1.8 inches at 133 lpi (266 ppi), which is sufficient for small brochures, advertisements, and catalog images. The next group of digital cameras, called mid-range, cost between $5,000 and $15,000. These cameras are essentially traditional Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera bodies. -

Openimageio 1.7 Programmer Documentation (In Progress)

OpenImageIO 1.7 Programmer Documentation (in progress) Editor: Larry Gritz [email protected] Date: 31 Mar 2016 ii The OpenImageIO source code and documentation are: Copyright (c) 2008-2016 Larry Gritz, et al. All Rights Reserved. The code that implements OpenImageIO is licensed under the BSD 3-clause (also some- times known as “new BSD” or “modified BSD”) license: Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without modification, are per- mitted provided that the following conditions are met: • Redistributions of source code must retain the above copyright notice, this list of condi- tions and the following disclaimer. • Redistributions in binary form must reproduce the above copyright notice, this list of con- ditions and the following disclaimer in the documentation and/or other materials provided with the distribution. • Neither the name of the software’s owners nor the names of its contributors may be used to endorse or promote products derived from this software without specific prior written permission. THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS AND CONTRIB- UTORS ”AS IS” AND ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FIT- NESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT OWNER OR CONTRIBUTORS BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUD- ING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABIL- ITY, OR TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THIS SOFTWARE, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE. -

Graphicconverter 6.6

User’s Manual GraphicConverter 6.6 Programmed by Thorsten Lemke Manual by Hagen Henke Sales: Lemke Software GmbH PF 6034 D-31215 Peine Tel: +49-5171-72200 Fax:+49-5171-72201 E-mail: [email protected] In the PDF version of this manual, you can click the page numbers in the contents and index to jump to that particular page. © 2001-2009 Elbsand Publishers, Hagen Henke. All rights reserved. www.elbsand.de Sales: Lemke Software GmbH, PF 6034, D-31215 Peine www.lemkesoft.com This book including all parts is protected by copyright. It may not be reproduced in any form outside of copyright laws without permission from the author. This applies in parti- cular to photocopying, translation, copying onto microfilm and storage and processing on electronic systems. All due care was taken during the compilation of this book. However, errors cannot be completely ruled out. The author and distributors therefore accept no responsibility for any program or documentation errors or their consequences. This manual was written on a Mac using Adobe FrameMaker 6. Almost all software, hardware and other products or company names mentioned in this manual are registered trademarks and should be respected as such. The following list is not necessarily complete. Apple, the Apple logo, and Macintosh are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Mac and the Mac OS logo are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Photo CD mark licensed from Kodak. Mercutio MDEF copyright Ramon M. Felciano 1992- 1998 Copyright for all pictures in manual and on cover: Hagen Henke except for page 95 exa- mple picture Tayfun Bayram and others from www.photocase.de; page 404 PCD example picture © AMUG Arizona Mac Users Group Inc. -

Nikon F6 Vs Canon EOS-1V Vs Leica R9

Battle of the Titans: NIKON F6 vs. CANON EOS-1v vs. LEICA R9 Shutter Release, April 2005 Revised March 2007 Canon got the better of Nikon and Leica on Internet forums in 2004 with regard to film cameras. If ad hoc quips about the world’s leading 35mm SLR cameras were to be believed, Canon had pulled ahead in optics and overall speed of operation. As to Leica, well, the legendary mark had already had its day and is a stodgy if reliable instrument years behind Canon and Nikon. The stereotypes were flat-out wrong, even before the introduction of the new Nikon F6 in late 2004. The reality is that each manufacturer has selectively invested in features for different users. Canon has led in technology to steady hand-held telephoto lenses. The Leica R9 provides ultimate finessing of manual with automatic controls to a precision of 0.1 f-stop (in multi-pattern metering), and is arguably the most user-friendly of the three cameras. The Nikon F6 is a more versatile and lighter redesign of the F5 that pioneered the most advanced autoexposure system available, engineered for accuracy in extreme or peculiar lighting conditions where other cameras would fall short. Features in Common The three flagship models are equipped to enable excellence in most photographic situations. Together with their abundant selections of optics and all manner of gadgetry, the top-of-line Nikon, Canon and Leica cameras have been widely considered the best in 35mm film photography. The Nikon F6, Canon EOS-1v and Leica R9 offer: Evaluative autoexposure: The microcomputer in the camera assesses a scene through an array of sensors, and applies an ideal aperture and/or shutter speed as fast as 1/8000 sec. -

Used Equipment 35Mm Cameras & Accessories

Used Equipment 35mm Cameras & Accessories Leica M6 Classic MF Camera Minolta Maxxum7xi AF Camera Nikon N8008S AF Camera Nikon N90s AF Camera Nikon SB-28 AF Speedlight Flash • Body Only • Auto Focus • Auto Focus • Auto Focus • Dedicated TTL • Manual Focus • Body Only • Body Only • Body Only Shoe Mount • Black Color • Guide No. 13 • Bounce, Swivel & Zoom Head Condition 9 Condition 8+ Condition 8+ Condition 8+ Condition 9 $1,699 $149 $185 $259 $129 Leica M6 Wetzlar MF Camera Minolta Maxxum 700si AF Camera Nikon N6006 AF Camera Nikon F5 AF Camera Kodak 80-210mm AF SLR Lens • Body Only • Auto Focus • Auto Focus • Auto Focus • For Nikon AF • Manual Focus • Body Only Body • Body Only • Auto Focus • Black Color • f/.-.6 Condition 9 Condition 8+ Condition 8+ Condition 8+ New $1,649 $179 $99 $799 $59.95 35mm SLR Cameras Bodies, Lenses, Flashes, Accessories CANON Canon FD Breech MT Lenses MINOLTA MD Lenses MT-2 Intervalometer (No cord) .................399 EOS Bodies 24/2.8 ..............................................9 ......199 Maxxum Bodies 24/2.8 ..............................................9 ......239 MH-2 ...............................................8+ .....49 620...................................................9 ......129 28/2.8 ..............................................8+ .....69 XTsi QD ............................................8+ .....79 28/3.5 Celtic ....................................8+ .....49 AC-1E ..............................................9 ........49 630 QD ............................................8+ ...139 28/3.5 -

CODE by R.Mutt

CODE by R.Mutt dcraw.c 1. /* 2. dcraw.c -- Dave Coffin's raw photo decoder 3. Copyright 1997-2018 by Dave Coffin, dcoffin a cybercom o net 4. 5. This is a command-line ANSI C program to convert raw photos from 6. any digital camera on any computer running any operating system. 7. 8. No license is required to download and use dcraw.c. However, 9. to lawfully redistribute dcraw, you must either (a) offer, at 10. no extra charge, full source code* for all executable files 11. containing RESTRICTED functions, (b) distribute this code under 12. the GPL Version 2 or later, (c) remove all RESTRICTED functions, 13. re-implement them, or copy them from an earlier, unrestricted 14. Revision of dcraw.c, or (d) purchase a license from the author. 15. 16. The functions that process Foveon images have been RESTRICTED 17. since Revision 1.237. All other code remains free for all uses. 18. 19. *If you have not modified dcraw.c in any way, a link to my 20. homepage qualifies as "full source code". 21. 22. $Revision: 1.478 $ 23. $Date: 2018/06/01 20:36:25 $ 24. */ 25. 26. #define DCRAW_VERSION "9.28" 27. 28. #ifndef _GNU_SOURCE 29. #define _GNU_SOURCE 30. #endif 31. #define _USE_MATH_DEFINES 32. #include <ctype.h> 33. #include <errno.h> 34. #include <fcntl.h> 35. #include <float.h> 36. #include <limits.h> 37. #include <math.h> 38. #include <setjmp.h> 39. #include <stdio.h> 40. #include <stdlib.h> 41. #include <string.h> 42. #include <time.h> 43. #include <sys/types.h> 44. -

Megaplus Conversion Lenses for Digital Cameras

Section2 PHOTO - VIDEO - PRO AUDIO Accessories LCD Accessories .......................244-245 Batteries.....................................246-249 Camera Brackets ......................250-253 Flashes........................................253-259 Accessory Lenses .....................260-265 VR Tools.....................................266-271 Digital Media & Peripherals ..272-279 Portable Media Storage ..........280-285 Digital Picture Frames....................286 Imaging Systems ..............................287 Tripods and Heads ..................288-301 Camera Cases............................302-321 Underwater Equipment ..........322-327 PHOTOGRAPHIC SOLUTIONS DIGITAL CAMERA CLEANING PRODUCTS Sensor Swab — Digital Imaging Chip Cleaner HAKUBA Sensor Swabs are designed for cleaning the CLEANING PRODUCTS imaging sensor (CMOS or CCD) on SLR digital cameras and other delicate or hard to reach optical and imaging sur- faces. Clean room manufactured KMC-05 and sealed, these swabs are the ultimate Lens Cleaning Kit in purity. Recommended by Kodak and Fuji (when Includes: Lens tissue (30 used with Eclipse Lens Cleaner) for cleaning the DSC Pro 14n pcs.), Cleaning Solution 30 cc and FinePix S1/S2 Pro. #HALCK .........................3.95 Sensor Swabs for Digital SLR Cameras: 12-Pack (PHSS12) ........45.95 KA-11 Lens Cleaning Set Includes a Blower Brush,Cleaning Solution 30cc, Lens ECLIPSE Tissue Cleaning Cloth. CAMERA ACCESSORIES #HALCS ...................................................................................4.95 ECLIPSE lens cleaner is the highest purity lens cleaner available. It dries as quickly as it can LCDCK-BL Digital Cleaning Kit be applied leaving absolutely no residue. For cleaing LCD screens and other optical surfaces. ECLIPSE is the recommended optical glass Includes dual function cleaning tool that has a lens brush on one side and a cleaning chamois on the other, cleaner for THK USA, the US distributor for cleaning solution and five replacement chamois with one 244 Hoya filters and Tokina lenses. -

Hugostudio List of Available Camera Covers

Exakta VX 1000 W/ P4 Finder Hugostudio List of Exakta VX 500 W/ H3.3 Finder Available Camera Covers Exakta VX IIa V1-V4 W/ P2.2 Finder Exakta VX IIa V5-V7-V8 _P3.3 Finder (1960) Exakta VX IIa V6 W/ H3 SLR Exakta VX IIb W/ P3 Asahiflex IIb Exakta VX IIb W/ P4 Finder Canon A-1 Exakta Varex VX V1 - V2 Canon AE-1 Exakta-Varex VX IIa V1-V4 Canon AE-1 Program Exakta Varex VX V4 V5 Canon AV-1 Exakta Varex VX W/ Finder P1 Canon EF Fujica AX-3 Canon EX Auto Fujica AZ-1 Canon F-1 Pic Req* Fujica ST 601 Canon F-1n (New) pic Req* Fujica ST 701 Canon FT QL Fujica ST 801 Canon FTb QL Fujica ST 901 Canon FTb n QL Kodak Reflex III Canon Power Winder A Kodak Reflex IV Canon TL-QL Kodak REflex S Canon TX Konica FT-1 Canonflex Konica Autoreflex T3 Chinon Memotron Konica Autoreflex T4 Contax 137 MA Konica Autoreflex TC Contax 137 MD Leica R3 Contax 139 Quartz Leica R4 Contax Motor Drive W6 Leica Motor Winder R4 Contax RTS Leicaflex SL Contax RTS II Mamiya ZE-2 Quartz Contax139 Quartz Winder Minolta Auto Winder D Edixa Reflex D Minolta Auto Winder G Exa 500 Minolta Motor Drive 1 Exa I, Ia, Ib Minolta SR 7 Exa II Minolta SRT 100 Exa IIa Minolta SRT 101 Exa Type 6 Minolta SRT 202 Exa VX 200 Minolta X370 Exa Version 2 to 5 Minolta X370s Exa Version 6 Minolta X570 Exa Version I Minolta X700 Exakta 500 Minolta XD 11, XD 5, XD 7, XD Exakta Finder H3 Minolta XE-7 XE-5 Exakta Finder: prism P2 Minolta XG-1 Exakta Finder: prism P3 Minolta XG 9 Exakta Finder: prism P4 Minolta XG-M Exakta Kine Minolta XG7, XG-E Exakta Meter Finder Minolta XM Exakta RTL1000 Miranda AII -

Photographica 24/03/2020 10:00 AM GMT

Auction - Photographica 24/03/2020 10:00 AM GMT Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 1 Canon Cameras and Lenses, comprising a Canon EOS D30 DSLR 15 Photographic Accessories, including 3 Linhof 6½ x 9 DDS film holders, a body, a Canon EOS 600 camera, a Canon T50 camera, a Canon T70 Schneider Xenar 16.5cm f/4.5 board-mounted lens with Compur shutter, camera, a Canon AE-1 Program camera, a Canonet rangefinder other lenses, some with leaf shutters, a JVC P-100UKC 6 volts 5cm camera, an EF 75-300mm lens and an EF 90-300mm lens (a lot) approx television, untested and other items Est. 50 - 70 Est. 30 - 50 2 Nikon SLR Cameras and Bodies, comprising a Nikon D70s DSLR 16 A Tray of Sub-Miniature 'Spy' Cameras, including a Minox B camera, a camera with an AF Nikkor 28-80mm lens, a Nikon D70 DSLR body, a Minox C camera, a Yashica Atoron camera and a Minolta 16 II camera, Nikon F-301 body, a Nikkormat FTN body, a Nikon EM body, an AF all in maker's cases, together with sundry related items Nikkor 70-210mm f/4-5.6 lens, boxed and a Speedlight SB-16 (a lot) Est. 70 - 100 Est. 50 - 70 17 A Tray of Ensign Midget and Other Sub-Miniature Cameras, a Model 22 3 Pentax M SLR Cameras, comprising three Pentax ME Super cameras, a camera, three Model 33 cameras, a Model 55 camera, a box of unused ME Super body, a MG camera and an MV 1 body (a lot) Ensign Lukos E10 film dated Dec 1935, a Kiku 16 Model II and a Speedex 'Hit-type' cameras, two United Optical Merlin cameras and a Est.