Essentials of Azerbaijani: an Introductory Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies on Language Change. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 34

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 286 382 FL 016 932 AUTHOR Joseph, Brian D., Ed. TITLE Studies on Language Change. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 34. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Linguistics. PUB DATE Dec 86 NOTE 171p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) -- Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Arabic; Diachronic Linguistics; Dialects; *Diglossia; English; Estonian; *Etymology; Finnish; Foreign Countries; Language Variation; Linguistic Borrowing; *Linguistic Theory; *Morphemes; *Morphology (Languages); Old English; Sanskrit; Sociolinguistics; Syntax; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; Word Frequency IDENTIFIERS Saame ABSTRACT A collection of papers relevant to historical linguistics and description and explanation of language change includes: "Decliticization and Deaffixation in Saame: Abessive 'taga'" (Joel A. Nevis); "Decliticization in Old Estonian" (Joel A. Nevis); "On Automatic and Simultaneous Syntactic Changes" (Brian D. Joseph); "Loss of Nominal Case Endings in the Modern Arabic Sedentary Dialects" (Ann M. Miller); "One Rule or Many? Sanskrit Reduplication as Fragmented Affixation" (Richard D. Janda, Brian D. Joseph); "Fragmentation of Strong Verb Ablaut in Old English" (Keith Johnson); "The Etymology of 'bum': Mere Child's Play" (Mary E. Clark, Brian D. Joseph); "Small Group Lexical Innovation: Some Examples" (Christopher Kupec); "Word Frequency and Dialect Borrowing" (Debra A. Stollenwerk); "Introspection into a Stable Case of Variation in Finnish" (Riitta Valimaa-Blum); -

Volume II, Issue 2, March 2021.Pages

INTERNATIONAL COUNTER-TERRORISM REVIEW VOLUME II, ISSUE 2 February, 2021 The Revival of Islam How Do External Factors Shape the Potential Islamist Threat in Azerbaijan? FUAD SHAHBAZOV ABOUT ICTR The International Counter-Terrorism Review (ICTR) aspires to be the world’s leading student publication in Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism Studies. ICTR provides a unique opportunity for students and young professionals to publish their papers, share innovative ideas, and develop an academic career in Counter-Terrorism Studies. The publication also serves as a platform for exchanging research and policy recommendations addressing theoretical, empirical and policy dimensions of international issues pertaining to terrorism, counter-terrorism, insurgency, counter-insurgency, political violence and homeland security. ICTR is a project jointly initiated by the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya, Israel and NextGen 5.0. The International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) is one of the leading academic institutes for counter-terrorism in the world. Founded in 1996, ICT has rapidly evolved into a highly esteemed global hub for counter-terrorism research, policy recommendations and education. The goal of the ICT is to advise decision makers, to initiate applied research and to provide high-level consultation, education and training in order to address terrorism and its effects. NextGen 5.0 is a pioneering non-profit, independent, and virtual think tank committed to inspiring and empowering the next generation of peace and security leaders in order to build a more secure and prosperous world. COPYRIGHT This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Narmina Rustamova Suleyman Rustam 14/23, Baku, Azerbaijan Mobile: (+994) 50 349 47 56 Email: Narmina [email protected]

Narmina Rustamova Suleyman Rustam 14/23, Baku, Azerbaijan Mobile: (+994) 50 349 47 56 email: [email protected] Experience Adjunct Instructor 01/2019 – present ADA University Baku, Azerbaijan Delivering lectures in Health Economics. Adjunct Instructor 01/2016 – 01/2017 ADA University Baku, Azerbaijan Delivered lectures in Quantitative Research Methods, Data Management and Data Analysis. Senior Advisor 01/2011-05/2012 State Committee for Securities of the Republic of Azerbaijan Baku, Azerbaijan Supervised financial intermediaries and lottery operators. Audited and determined risk categories of market participants. Developed legislation on financial markets. Conducted negotiations with international organizations. Adjunct Professor 06/2010-12/2011 Baku State University Baku, Azerbaijan Delivered lectures in Accounting and International Economic Relationships. Developed education programs and examination database. Education PhD in Economics 03/2018 – present Baku State University Baku, Azerbaijan Master of Arts in Economics 07/2008-06/2010 Central European University Budapest, Hungary Bachelor in Economic Cybernetics 09/2004-06/2008 Baku State University Baku, Azerbaijan Professional Developments/Trainings • Participant in the project on “Economic North-Caucasus Federal University diplomacy in the development of Eurasian Pyatigorsk, Russia, 2018 integration” • Participant in the courses for Graduate Studies CERGE-EI in Economics Prague, Czech Republic, 2012 – 2014 • Participant in the seminar on “Tools for onsite Capital Markets -

Answering Particles: Findings and Perspectives

ANSWERING PARTICLES: FINDINGS AND PERSPECTIVES Emilio Servidio ([email protected]) 1. ANSWERING SYSTEMS 1.1. Historical introduction It is not uncommon for descriptive or prescriptive grammars to observe that a given language follows certain regularities when answering a polar question. Linguistics, on the other hand, has seldom paid much attention to the topic until recent years. The forerunner, in this respect, is Pope (1973), who sketched a typology of polar answering systems that followed in the steps of recent typological efforts on related topics (Ultan 1969, Moravcsik 1971 on polar questions). In the last decade, on the other hand, contributions have appeared from two different strands of theoretical research, namely, the syntactic approach to ellipsis as deletion (Kramer & Rawlins 2010; Holmberg 2013, 2016) and the study of conversation dynamics (Farkas & Bruce 2010; Krifka 2013, 2015; Roelofsen & Farkas 2015). This contribution aims at offering a critical overview of the state of the art on the topic1. In the remainder of this section, a typological sketch of answering systems will be drawn, before moving on to the extant analyses in section 2. In section 3, recent experimental work will be discussed. Section 4 summarizes and concludes. 1.2. Basic typology This survey will mainly deal with polar answers, defined as responding moves that address and fully satisfy the discourse requirements of a polar question. A different but closely related topic is the one of replies, i.e., moves that respond to a statement. Together, these moves go under the name of responses2. One first piece of terminology is the distinction between short and long responses. -

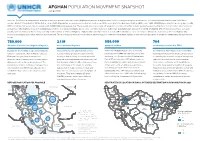

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Similarities and Dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: a Comparative Study

Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic 94 Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: A Comparative Study MD YEAQUB Research Scholar Aligarh Muslim University, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper will focus on a comparative study about similarities and dissimilarities of the pronunciation between the syllables of English and Arabic with the help of phonetic and phonological tools i.e. manner of articulation, point of articulation and their distribution at different positions in English and Arabic Alphabets. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the alphabets of English and Arabic can be useful in overcoming the hindrances for those want to improve the pronunciation of both English and Arabic languages. We all know that Arabic is a Semitic language from the Afro-Asiatic Language Family. On the other hand, English is a West Germanic language from the Indo- European Language Family. Both languages show many linguistic differences at all levels of linguistic analysis, i.e. phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, etc. For this we will take into consideration, the segmental features only, i.e. the consonant and vowel system of the two languages. So, this is better and larger to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learners’ outcomes. Keywords: Arabic Alphabets, English Alphabets, Pronunciations, Phonetics, Phonology, manner of articulation, point of articulation. Introduction: We all know that sounds are generally divided into two i.e. consonants and vowels. A consonant is a speech sound, which obstruct the flow of air through the vocal tract. -

56. Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity When Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions

University of Southern California Law From the SelectedWorks of Thomas D. Lyon December 19, 2016 56. Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity when Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions. Angela D. Evans, Brock University Stacia N. Stolzenberg, Arizona State University Thomas D. Lyon Available at: https://works.bepress.com/thomaslyon/139/ Psychology, Public Policy, and Law © 2017 American Psychological Association 2017, Vol. 23, No. 2, 191–199 1076-8971/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000116 Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity When Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions Angela D. Evans Stacia N. Stolzenberg Brock University Arizona State University, Tempe Thomas D. Lyon University of Southern California “Do you know” and “Do you remember” (DYK/R) questions explicitly ask whether one knows or remembers some information while implicitly asking for that information. This study examined how 4- to 9-year-old (N ϭ 104) children testifying in child sexual abuse cases responded to DYK/R wh- (who, what, where, why, how, and which) and yes/no questions. When asked DYK/R questions containing an implicit wh- question requesting information, children often provided unelaborated “yes” responses. Attorneys’ follow-up questions suggested that children usually misunderstood the pragmatics of the questions. When DYK/R questions contained an implicit yes/no question, unelaborated “yes” or “no” responses could be responding to the explicit or the implicit questions resulting in referentially ambig- uous responses. Children often provided referentially ambiguous responses and attorneys usually failed to disambiguate children’s answers. Although pragmatic failure following DYK/R wh- questions de- creased with age, the likelihood of referential ambiguity following DYK/R yes/no questions did not. -

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty: Education Major: General and Applied Linguistics Topic: “May your young people cast off the stone of singleness:” Azerbaijani “alqış phrases” (blessing formulas) and their American English equivalents, or what is revealed by the lack thereof Master student: Martha Lawry Scientific Advisor: Professor Hamlet Isaxanli Submitted January 2012 1 Summary This thesis by Martha Lawry is entitled “„may your young people cast off the stone of singleness:‟ Azerbaijani „alqış phrases‟ (blessing formulas) and their American English equivalents, or what is revealed by the lack thereof.” The objective of the research is to define the alqış phrases which are frequently used in modern spoken Azerbaijani, determine how best to define them in English, determine their linguistic functions in Azerbaijani, and compare them to the phrases that most closely fulfill the same functions in American English. Ethnographic and comparative research methods were used, including reviewing secondary sources (literature reviews) and qualitative research in the form of both semi- structured interviews conducted with native Azerbaijani speakers of varying ages and social strata living in the Azerbaijan Republic and open-ended structured interviews conducted via an online questionnaire with native English speakers living in the United States. The research led to the conclusion that alqış phrases should be defined as ―blessing formulas‖ in English. Most alqış phrases were determined to be grammatically distinguished by second or third person verbs in optative or imperative mood. They can have the expressive functions of being bono-recognitive, bono-petitive, malo-recognitive or malo-fugitive, although the most common are bono-petitive and malo-fugitive. Alqış phrases were also shown to be politeness strategies according to Levinson and Brown‘s politeness theory (used to protect the speaker‘s positive face or to protect the listener‘s negative face). -

Attachement 2 Inter-Ethnic Conflicts in Kazakhstan

ATTACHEMENT 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN KAZAKHSTAN BETWEEN 2006 AND 2007 Events in Aktau On August 20, 2006 Aktau City witnessed riots. Printed mass media reported that originally an unauthorized but peaceful rally of workers was taking place at the central square of the city Yntymak. The workers of Mangistau MunayGas OJSC were demanding salary increase. According to City Akimat (local authority), around 10 or 15 people were participating in the rally. Next day information leaked to the press that there were more than 200 people gathered at the square by night. According to city authorities small groups from the rally moved to courtyards of resident buildings and tried to organize pogroms. Other sources speak about clashes with police and number of arrested vary between 17 and 25 persons. Participants of the rally were joined by the youth who started violent clashes with the police. Opposition mass media reported that at that moment some people in crowed began screaming racial offenses against the Caucasians who live in the area and then began to smash cafeterias and shops owned by Lezgins, Chechens and Azerbaijanis. Mangyshlak peninsula which hosts port city of Aktau has already several times been a field of interethnic conflicts. The most notorious one is a massacre in New Ozen (currently Zhanaozen) of summer 1989 when indigenous people had bloody fights with Lezgins and Chechens. From time to time local conflicts between indigenous people, i.e. Kazakhs, and representatives of the Caucasian diasporas take place in villages of Mangyshlak peninsula. As a rule conflicts arise out of incidents of a criminal nature. -

What It Means and What’

Cracking Down on Creative Voices: Turkey’s Silencing of Writers, Intellectuals, and Artists Five Years After the Failed Coup Thank you for joining us for Cracking Down on Creative Voices: Turkey’s Silencing of Writers, Intellectuals, and Artists Five Years After the Failed Coup Since the attempted coup d’état in 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has elevated his attacks on Turkey’s civil society to unprecedented levels, becoming one of the world’s foremost persecutors of freedom of expression. In the five years since the attempted coup, dozens of writers, activists, artists, and intellectuals have been targeted, prosecuted, and jailed; 29 publishing houses have been closed; over 135,000 books have been banned from Turkish public libraries; and more than 5,800 academics have been dismissed from their posts for expressing dissent. PEN America’s 2020 Freedom to Write Index found that Turkey was the world’s third highest imprisoner of writers and public intellectuals, with at least 25 cases of detention or imprisonment. This repressive climate has left writers and other members of Turkey’s cultural sector feeling embattled and targeted, unsure of what they can say or write without falling into their government’s crosshairs. PEN America, the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), and members of Turkey’s cultural, artistic, and literary communities discussed these trends and made recommendations on how policymakers might respond to Erdoğan’s campaign of repression. The discussion highlighted PEN America’s report on freedom of expression in Turkey, which features interviews from members of Turkey’s literary, cultural, and human rights communities to better understand how this society- wide crackdown has affected freedom of expression within the country. -

Minimalist C/Case Sigurðsson, Halldor Armann

Minimalist C/case Sigurðsson, Halldor Armann Published in: Linguistic Inquiry 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sigurðsson, H. A. (2012). Minimalist C/case. Linguistic Inquiry, 43(2), 191-227. http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000967 Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Access Provided by Lunds universitet at 04/30/12 3:55PM GMT Minimalist C/case Halldo´rA´ rmann SigurLsson This article discusses A-licensing and case from a minimalist perspec- tive, pursuing the idea that argument NPs cyclically enter a number of A-relations, rather than just a single one, resulting in event licensing, case licensing, and -licensing. -

Arabic Sociolinguistics: Topics in Diglossia, Gender, Identity, And

Arabic Sociolinguistics Arabic Sociolinguistics Reem Bassiouney Edinburgh University Press © Reem Bassiouney, 2009 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in ll/13pt Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and East bourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 2373 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 2374 7 (paperback) The right ofReem Bassiouney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements viii List of charts, maps and tables x List of abbreviations xii Conventions used in this book xiv Introduction 1 1. Diglossia and dialect groups in the Arab world 9 1.1 Diglossia 10 1.1.1 Anoverviewofthestudyofdiglossia 10 1.1.2 Theories that explain diglossia in terms oflevels 14 1.1.3 The idea ofEducated Spoken Arabic 16 1.2 Dialects/varieties in the Arab world 18 1.2. 1 The concept ofprestige as different from that ofstandard 18 1.2.2 Groups ofdialects in the Arab world 19 1.3 Conclusion 26 2. Code-switching 28 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Problem of terminology: code-switching and code-mixing 30 2.3 Code-switching and diglossia 31 2.4 The study of constraints on code-switching in relation to the Arab world 31 2.4. 1 Structural constraints on classic code-switching 31 2.4.2 Structural constraints on diglossic switching 42 2.5 Motivations for code-switching 59 2.