Alienation in the Work of Tom Leonard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic

Notes Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic 1. Caroline McCracken-Flesher, writing shortly before the latter film’s release, argues that it is, like the former, ‘still an outsider tale’; despite the emphasis on ‘Scottishness’ within these films, they could only emerge from outside Scotland. Caroline McCracken-Flesher (2012) The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 20. 2. Kirsty A. MacDonald (2009) ‘Scottish Gothic: Towards a Definition’, The Bottle Imp, 6, 1–2, p. 1. 3. Andrew Payne and Mark Lewis (1989) ‘The Ghost Dance: An Interview with Jacques Derrida’, Public, 2, 60–73, p. 61. 4. Nicholas Royle (2003) The Uncanny (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 12. 5. Allan Massie (1992) The Hanging Tree (London: Mandarin), p. 61. 6. See Luke Gibbons (2004) Gaelic Gothic: Race, Colonization, and Irish Culture (Galway: Arlen House), p. 20. As Coral Ann Howells argues in a discussion of Radcliffe, Mrs Kelly, Horsley-Curteis, Francis Lathom, and Jane Porter, Scott’s novels ‘were enthusiastically received by a reading public who had become accustomed by a long literary tradition to associate Scotland with mystery and adventure’. Coral Ann Howells (1978) Love, Mystery, and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction (London: Athlone Press), p. 19. 7. Ann Radcliffe (1995) The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, ed. Alison Milbank (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 3. 8. As James Watt notes, however, Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne remains a ‘derivative and virtually unnoticed experiment’, heavily indebted to Clara Reeves’s The Old English Baron. James Watt (1999) Contesting the Gothic: Fiction, Genre and Cultural Conflict, 1764–1832 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. -

A Parliament of Novels: the Politics of Scottish Fiction 1979-1999 Un Parlement Dans La Littérature : Politique Et Fiction Écossaise 1979-1999

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XIV-1 | 2006 La dévolution des pouvoirs à l'Écosse et au Pays de Galles 1966-1999 A Parliament of Novels: the Politics of Scottish Fiction 1979-1999 Un parlement dans la littérature : politique et fiction écossaise 1979-1999 David Leishman Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/1175 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.1175 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 2 January 2006 Number of pages: 123-136 ISBN: 2–911580–23–0 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference David Leishman, « A Parliament of Novels: the Politics of Scottish Fiction 1979-1999 », Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XIV-1 | 2006, Online since 15 October 2016, connection on 02 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/1175 ; DOI : 10.4000/rfcb.1175 Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. A Parliament of Novels : the Politics of Scottish Fiction 1979-1999 David LEISHMAN Université de Grenoble 3 The Scottish literary scene enjoyed so great a resurgence at the end of the 20th century that the period has sometimes been termed the second Scottish renaissance.1 After a period of relative moroseness, initially exacerbated by the 1979 referendum result,2 Scottish fiction found a new vitality which can be charted by a number of factors: the strong growth in the number of new novels published;3 the linguistic, narratological and typographic experimentation of authors such as Alasdair Gray, James Kelman or Janice Galloway; the increased critical interest in Scottish letters; the commercial success of authors such as Ian Rankin or Irvine Welsh, who, despite their international popularity, remain distinctively Scottish in terms of orientation or voice. -

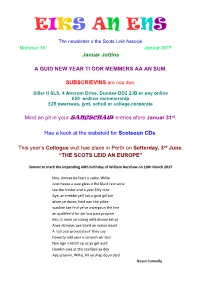

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — 'Notes Personal' in Response to His Life

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — ‘Notes Personal’ in Response to his Life and Work an essay by Jim Ferguson 1. How I met the human being named ‘Tom Leonard’ I was ill with epilepsy and post-traumatic stress disorder. It was early in 1986. I was living in a flat on Causeyside Street, Paisley, with my then partner. We were both in our mid-twenties and our relationship was happy and loving. We were rather bookish with quite a strong sense of Scottish and Irish working class identity and an interest in socialism, social justice. I think we both held the certainty that the world could be changed for the better in myriad ways, I know I did and I think my partner did too. You feel as if you share these basic things, a similar basic outlook, and this is probably why you want to live in a little tenement flat with one human being rather than any other. We were not career minded and our interest in money only stretched so far as having enough to live on and make ends meet. Due to my ill health I wasn’t getting out much and rarely ventured far from the flat, though I was working on ‘getting better’. In these circumstances I found myself filling my afternoons writing stories and poems. I had a little manual portable typewriter and would sit at a table and type away. I was a very poor typist which made poetry much more appealing and enjoyable because it could be done in fewer words with a lot less tipp-ex. -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002. -

"Dae Scotsmen Dream O 'Lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 "Dae Scotsmen Dream o 'lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland Alexander Burke Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i © Alexander P. Burke 2013 All Rights Reserved i “Dae Scotsmen Dream o ‘lectric Leids?” Robert Crawford’s Cyborg Scotland A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English at Virginia Commonwealth University By Alexander Powell Burke Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University May 2011 Director: Dr. David Latané Associate Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2013 ii Acknowledgment I am forever indebted to the VCU English Department for providing me with a challenging and engaging education, and its faculty for making that experience enjoyable. It is difficult to single out only several among my professors, but I would like to acknowledge David Wojahn and Dr. Marcel Cornis-Pope for not only sitting on my thesis committee and giving me wonderful advice that I probably could have followed more closely, but for their role years prior of inspiring me to further pursue poetry and theory, respectively. -

The Characters' Response to Social Structures in Alasdair Gray's Lanark

Compliance Versus Defiance: The Characters’ Response to Social Structures in Alasdair Gray’s Lanark and 1982 Janine Markéta Gregorová Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic Abstract The article focuses on two novels by Alasdair Gray, Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981) and 1982 Janine (1984), in particular on the ways in which the characters are influenced by externally imposed social structures and the attitudes they assume in dealing with them. The adverse workings of official institutions, such as education and employment facilities, are received with compliance on the part of the protagonist in 1982 Janine but meet with resistance from both of the two mirror protagonists in Lanark. In the context of the standing of Scotland within the United Kingdom, institutions represent the interests of the powerful English majority rather than the dependent Scottish minority, and therefore any act of rebellion against them is charged with a subversive potential. Besides the political implications, the article explores the social dimensions of the novels and illustrates by means of individual examples the means used by the powerful to exploit the powerless, as well as the strategies the latter employ to defend themselves. Keywords Alasdair Gray; Lanark; 1982 Janine; politics in literature; sexuality; twentieth-century Scottish literature When Alasdair Gray was asked by an interviewer whether the concern with monstrous institutions recurrent in his writing is a “kind of obstreperousness” springing from “a genetic perturbation” of the author, he replied: My approach to institutional dogma and criteria—let’s call it my approach to institutions—reflects their approach to me. Nations, cities, schools, marketing companies, hospitals, police forces have been made by people for the good of people. -

08.2013 Edinburgh International Book Festival

08.2013 Edinburgh International Book Festival Celebrating 30 years Including: Baillie Gifford Children’s Programme for children and young adults Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters The Edinburgh International Book Festival is funded by Benefactors James and Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff and Mary Ball Lel and Robin Blair Richard and Catherine Burns Kate Gemmell Murray and Carol Grigor Fred and Ann Johnston Richard and Sara Kimberlin Title Sponsor of Schools and Children’s Alexander McCall Smith Programmes & the Main Theatre Media Partner Fiona Reith Lord Ross Richard and Heather Sneller Ian Tudhope and Lindy Patterson Claire and Mark Urquhart William Zachs and Martin Adam and all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The Barrack Charitable Trust The Binks Trust Booker Prize Foundation Major Sponsors and Supporters Carnegie Dunfermline Trust The John S Cohen Foundation The Craignish Trust The Crerar Hotels Trust The final version is the white background version and applies to situations where only the wordmark can be used. Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The MacRobert Trust Matthew Hodder Charitable Trust The Morton Charitable Trust SINCE Scottish New Park Educational Trust Mortgage Investment The Robertson Trust 11 Trust PLC Scottish International Education Trust 909 Over 100 years of astute investing 1 Tay Charitable Trust Programme Supporters Australia Council for the Arts British Centre for Literary Translation and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Edinburgh Unesco City of Literature Goethe Institute Italian Cultural Insitute The New Zealand Book Council Sponsors and Supporters NORLA (Norwegian Literature Abroad) Publishing Scotland Scottish Poetry Library South Africa’s Department of Arts and Culture Word Alliance With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. -

Meet Author Alan Bissett Sporting Achievements the Stirling Fund

2012 alumni, staff and friends Meet author alan Bissett The 2011 Glenfiddich SpiriT of ScoTland wriTer of The year sporting achieveMents our STirlinG SporTS ScholarS the stirling Fund we Say Thank you 8 12 16 4 NEWS HIGHLIGHTS Successes and key developments 8 ALAN BISSETT Putting words on paper and on screen 12 HAZEL IRVINE An Olympic career 14 SPORT at STIRLING contents Thirty years of success 16 RESEARCH ROUND UP Stirling's contribution 38 18 MEET THE PRINCIPAL An interview with Professor Gerry McCormac 20 THE LOST GENERatiON? Graduate employment prospects 22 GOING WILD IN THE ARCHIVES Exhibition on campus 22 24 A CELEBRatiON OF cOLOUR AND SPRING Book launches at the University 25 THE STIRLING FUND Donations and developments 29 29 ADOPT A BOOK Support our campaign 31 CLASS NOTES 43 Find your friends 37 A WORD FROM THE PRESIDENT Your chance to get involved 38 MAKING THEIR MARK Graduates tell their story 43 WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Senior concierges in the halls 45 EVENTS FOR YOUR DIARY Let us entertain you 2 / stirling minds / Alumni, staff and Friends reasons to keep 10 in touch With over 44,000 Stirling alumni in 151 countries around the world there welcome are many reasons why you should keep in touch: Welcome to the 2012 edition of Stirling Minds which provides a glimpse into what has been an exciting 1. Maintain lifelong friendships. year for the University – from the presentation of 2. Network. Connection with the new Strategic Plan in the Scottish Parliament last alumni in similar fields, September to the ranking in a new THE (under 50 positions and locations. -

Friends Newsletter

friends newsletter summer 2017 Note from the Editor: Priscilla Barlow This is my 10th year editing the splendid illustration of books on the Friends of the Argyll Papers Newsletter. newsletter – this being the 20th issue. GUL shelves; just a wee memory jog When I eventually bury my editor’s For the first two years I co-edited with reminding us that not everything is hatchet, I know the newsletter will be in Dr David Fergus. Over these years we digitised - although you might well be safe and creative hands. changed from dashing purple and green reading this online. We continue the now familiar format print to monochrome and eventually Duncan Beaton, who has been a with Friends news, Library news and to full colour; from 4 pages to 8. We Friend for a decade and a committee articles of bibliographical interest and as are currently working with our third member for 3 years, now affords me always we are well illustrated. To all our designer and we progressed from no the luxury of an assistant editor. He is contributors who continue to meet our particular masthead to a book spine, well versed in the intricacies of desktop deadlines, I give my thanks. then a view of the Library and now a publishing and already edits the The Priscilla Barlow: [email protected] The David Murray Book Collecting Prize The David Murray Book Collecting Prize, inaugurated this year, was made available through a generous donation of £500 and was open to all currently matriculated students of the University of Glasgow. An additional £500 was awarded to the winner to help select a new acquisition for Archives and Special Collections. -

Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 13 | Issue 1 Article 19 1978 Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Scott, Alexander (1978) "Scottish Poetry 1974-1976," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 13: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol13/iss1/19 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alexander Scott Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 For poetry in English, the major event of the period, in 1974, was the publication by Secker and Warburg, London, of the Com plete Poems of Andrew Young (1885-1971), arranged and intro duced by Leonard Clark. Although Young had lived in England since the end of the First World War, and had so identified himself with that country as to exchange his Presbyterian min istry for the Anglican priesthood in 1939, his links with Scotland where he was born (in Elgin) and educated (in Edin burg) were never broken, and he retained "the habit of mind that created Scottish philosophy, obsessed with problems of perception, with interaction between the 'I' and the 'Thou' and the 'I' and the 'It,."l Often, too, that "it" was derived from his loving observation of the Scottish landscape, to which he never tired of returning. Scarcely aware of any of this, Mr. Clark's introduction places Young in the English (or Anglo-American) tradition, in "the field company of John Clare, Robert Frost, Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas and Edmund Blunden ••• Tennyson and Browning may have been greater influences." Such a comment overlooks one of the most distinctive qualities of Young's nature poetry, the metaphysical wit that has affinities with those seven teenth-century poets whose cast of mind was inevitably moulded by their religion. -

Alan Bissett

Alan Bissett Agent: Jonathan Kinnersley ([email protected]) Alan is a Scottish writer for screen, stage and page (the latter represented by AM Heath). Alan’s one man show (MORE) MOIRA MONOLOGUES won a Fringe First at the Edinburgh Festival in 2017 and was nominated for ‘Best New Play’ at the Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland. It’s a sequel to THE MOIRA MONOLOGUES, which enjoyed two sold-out Edinburgh Fringe runs, numerous tours and whose lead character was declared ‘The most charismatic character to appear on a Scottish stage in a decade’ ★★★★ (Scotsman). Reviews: ★★★★★ – The Scotsman ★★★★ – The List ★★★★★ – Broadway Baby ★★★★★ – The National Scot ★★★★ – Edinburgh Spotlight In 2016 Alan’s play ONE THINKS OF IT ALL AS A DREAM toured Scotland, having been commissioned by the Scottish Mental Health Arts and Film Festival. It’s an ‘insightful eulogy’ (The Guardian) for the former Pink Floyd frontman, Syd Barrett: ★★★★ - ‘a lovingly and intensively researched play’ –The Herald ★★★★– ‘impressive, perfectly-judged’ – The Scotsman ‘a gem…beautifully honed and truly evocative mini-drama’ – The Sunday Herald Alan’s first play, THE CHING ROOM, a co-production between Glasgow’s Oran Mor and Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, ran at both theatres in March 2009 to great critical acclaim. It since been revived at Glasgow’s Citizens Theatre, the Royal Exchange, Manchester and in Philadelphia. Alan also collaborated with The Moira Monologues’ director Sacha Kyle on TURBO FOLK (Oran Mor) which was nominated for Best New Play at the 2010 Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland, and BAN THIS FILTH! which was shortlisted for an Amnesty International Freedom of Expression Award in 2013.