Creating Tomorrow Together [ 6 S 5 (

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

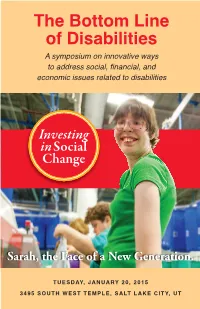

The Bottom Line of Disabilities 2015

The Bottom Line of Disabilities A symposium on innovative ways to address social, financial, and economic issues related to disabilities Inesting in Social Change Sarah, the Face of a New Generation. TUESDAY, JANUARY 20, 2015 3495 SOUTH WEST TEMPLE, SALT LAKE CITY, UT EVENT PARTNERS Columbus Community Center (www.columbusserves.org) is recognized locally and nationally as a well-established, innovative nonprofit agency. Columbus works strategically with many stakehold - ers to support individuals with disabilities so they can make informed decisions and live with in - dependence in the community. After nearly five decades of serving thousands of individuals, Columbus is still finding innovative ways to provide individuals with disabilities the support to live with independence and dignity in our community. The Global Interdependence Center (www.interdependence.org) is a neutral convener of dialogue, organizing conferences and roundtable discussions around the country and around the world to identify and address important global issues. Its programming promotes global partnerships among government officials, financial institutions, businesses leaders, and academic researchers. EVENT SPONSORS AGENDA EVENT EMCEES 8:30 A.M. TO 9:30 A.M. Michael Drury, McVean Trading The Policies that Shape Opportunity, & Investments Controversy, and Change Stephanie Mackay, Columbus Public policy and traditional funding sources have created safety nets, pro - vided opportunity for community inte - gration, and given a voice to some of the most vulnerable in our communi - ties. There have been significant social changes as well as some unintended 7:30 A.M. TO 8 A.M. consequences. Registration & Continental Breakfast MODERATOR: Palmer DePaulis, Former 8:00 A.M. TO 8:30 A.M. -

Newsletter02.Pdf

Fall 2002 sion at the University. A committee has Now I am sounding like a politician get- From the Director been formed. Could the Institute become ting ready to run for re-election. But I am a center for policy work? Should it seek so proud of what we have done, and of the expansion? How about new programs? great work of our staff, that I just want to These are just some of the questions the crow a little. Please excuse me. And I am committee will explore. After thirty-seven not running again! years of excellence, “If it ain’t broke, don’t I still need to work. I’m looking for fix it,” must apply. But it is also timely to some consulting opportunities. I would look to the future. like to hang out here through some teach- I often contemplate the wonderful char- ing. I will aid the new director as coal sketch of our founder Robert H. requested. The Hinckley Institute of Hinckley by Alvin Gittins that warms my Politics and the University of Utah will office. The eyes focus on the future. The remain a big part of my life. face is filled with compassion yet reflects a But there are mountains to climb- no-non-sense attitude. Par-ti-ci-pa-tion - as motorcycles to rev-grandchildren to hug- Mr. Hinckley said it while emphasizing and “many a mile before I sleep.” every syllable - is what we are about. And participation is what my staff and I have sought to deliver. I will miss my second family. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Downtown Salt Lake City We’Re Not Your Mall

DOWNTOWN SALT LAKE CITY WE’RE NOT YOUR MALL. WE’RE YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD. What if you took the richest elements of an eclectic, growing city and distilled them into one space? At The Gateway, we’re doing exactly that: taking a big city’s vital downtown location and elevating it, by filling it with the things that resonate most with the people who live, work, and play in our neighborhood. SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH STATE FOR BUSINESS STATE FOR STATE FOR #1 - WALL STREET JOURNAL, 2016 #1 BUSINESS & CAREERS #1 FUTURE LIVABILITY - FORBES, 2016 - GALLUP WELLBEING 2016 BEST CITIES FOR CITY FOR PROECTED ANNUAL #1 OB CREATION #1 OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES #1 OB GROWTH - GALLUP WELL-BEING 2014 - OUTSIDE MAGAZINE, 2016 - HIS GLOBAL INSIGHTS, 2016 LOWEST CRIME IN NATION FOR STATE FOR ECONOMIC #6 RATE IN U.S. #2 BUSINESS GROWTH #1 OUTLOOK RANKINGS - FBI, 2016 - PEW, 2016 - CNBC, 2016 2017 TOP TEN BEST CITIES FOR MILLENNIALS - WALLETHUB, 2017 2017 DOWNTOWN SALT LAKE CITY TRADE AREA .25 .5 .75 mile radius mile radius mile radius POPULATION 2017 POPULATION 1,578 4,674 8,308 MILLENNIALS 34.32% 31.95% 31.23% (18-34) EDUCATION BACHELOR'S DEGREE OR 36.75% 33.69% 37.85% HIGHER HOUSING & INCOME 2017 TOTAL HOUSING 1,133 2,211 3,947 UNITS AVERAGE VALUE $306,250 $300,947 $281,705 OF HOMES AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD $60,939 60,650 57,728 INCOME WORKFORCE TOTAL EMPLOYEES 5,868 14,561 36,721 SOURCES: ESRI AND NEILSON ART. ENTERTAINMENT. CULTURE. The Gateway is home to several unique entertainment destinations, including Wiseguys Comedy Club, The Depot Venue, Larry H. -

The Geographical Analysis of Mormon Temple Sites in Utah

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1992 The Geographical Analysis of Mormon Temple Sites in Utah Garth R. Liston Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Geography Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Liston, Garth R., "The Geographical Analysis of Mormon Temple Sites in Utah" (1992). Theses and Dissertations. 4881. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4881 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 the geographicalgeograp c ananalysisysls 0off mormormonon tetempletempiepie slsitessltestes in utah A thesis presented to the department of geography brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requiaequirequirementsrementscements for the degree master of science by garth R listenliston december 1992 this thesis by garth R liston is accepted in its present form by the department of geography of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of master of science f c- H L ricirichardard H jackson 1 committeeoommittee chair alan H grey committecommifctemeflermeymere er i w i ige-e&e date laieialeidleaaleig- J 6tevstevtpvnstldepartmentni d- epartmentepartment chair n dedication0 0 this thesis is dedicated to my wonderful mother -

Salt Lake City Arts Council Strategic Plan

2017-2020 Salt Lake City Arts Council Strategic Plan 2017-2020 Introduction The Salt Lake City Council on the Arts was formed in 1976 at the request of Mayor Ted Wilson, who appointed its first Executive Director. The Council was created to help distribute funds to arts organizations within the City, taking the burden off the City Commission. By 1979 a nonprofit entity, The Salt Lake Arts Council Foundation, was established to manage funds designated for the arts organization and also begin programming of their own. The two staff members of the Foundation were City employees. In 1981, this new group moved into the Art Barn, located in the City’s Reservoir Park, when the space was vacated by the Salt Lake Arts Center. From that initial beginning, the organization now has six full-time City employees who, together with the Foundation board, have grown the original concept into a significant cultural entity in the City. The Salt Lake City Arts Council is the City’s designated local arts agency and uses its unique position as manager of both public and received-grant resources to leverage how the arts are supported and presented to the City. Through its work, the Council has created enduring connections between the arts and the public, cultivated future artists and arts organizations, given voice to community arts conversations and needs, provided resources for arts programming, offered education about the arts as well as support of arts education efforts, and impacted City policy affecting the arts. It has developed its own programs, as well, that have endured for decades and serve as models for other arts programming. -

Non-Mormon Presence in 1880S Utah

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences THE WASP IN THE BEEHIVE: NON-MORMON PRESENCE IN 1880S UTAH A Thesis in Geography by Samuel A. Smith c 2008 Samuel A. Smith Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2008 The thesis of Samuel A. Smith was read and approved1 by the following: Deryck W. Holdsworth Professor of Geography Thesis Adviser Roger Downs Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography 1. Signatures on file in the Graduate School. iii Abstract Recent studies have reconsidered the Mormon Culture Region in light of its 1880{1920 transition to American political and economic norms. While these studies emphasize conflicts between the Mormon establishment and the non-Mormon federal government, Mormon/non-Mormon relations within Utah have received little direct attention. Based on religious affiliations recorded in the 1880 federal census of Utah Territory, this study uses historical GIS to visualize the composition of Utah's \Mormon" and \non-Mormon" towns. The results highlight the extensive presence of religious minorities in Utah's settlements. Case studies of farm villages, mining camps, and urban neighborhoods probe the social and economic contexts of non-Mormon presence in Utah. These studies, based on Sanborn maps and city directories, explore the geographical mosaic of Mormon and non-Mormon residence and business activity. These variegated patterns, often absent from historical accounts of the region, enable localized analyses of the ensuing decades of cultural conflict, transformation and assimilation. Keywords: Mormons, non-Mormons, Mormon Culture Region, Utah, 1880 Cen- sus, historical demography. -

Utah Women's Walk Oral Histories Directed by Michele Welch

UTAH VALLEY UNIVERSITY Utah Valley University Library George Sutherland Archives & Special Collections Oral History Program Utah Women’s Walk Oral Histories Directed by Michele Welch Interview with Melissa (Missy) Larsen by Anne Wairepo December 7, 2018 Utah Women’s Walk TRANSCRIPTION COVER SHEET Interviewee: Melissa Wilson Larsen Interviewer: Anne Wairepo Place of Interview: George Sutherland Archives, Fulton Library, Utah Valley University Date of Interview: 7 December 2018 Recordist: Richard McLean Recording Equipment: Zoom Recorder H4n Panasonic HD Video Camera AG-HM C709 Transcribed by: Kristiann Hampton Audio Transcription Edit: Kristiann Hampton Reference: ML = Missy Larsen (Interviewee) AW= Anne Wairepo (Interviewer) SD = Shelli Densley (Assistant Director, Utah Women’s Walk) Brief Description of Contents: Missy Larsen describes her experiences growing up in Salt Lake City, Utah during the time her dad, Ted Wilson, was the mayor. She also explains her own experiences serving in student government during her school years. Missy talks about being a young wife and mother while working as the press secretary for Bill Orton. She further explains how she began her own public relations company, Intrepid. Missy details how she helped Tom Smart with publicity during the search for his daughter Elizabeth Smart who was abducted from her home in 2002. She talks about her position as chief of staff to Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes and her involvement in developing the SafeUT app, which is a crisis intervention resource for teens. She concludes the interview by talking about the joy she finds in volunteering her time to help refugees in Utah. NOTE: Interjections during pauses or transitions in dialogue such as uh and false starts and stops in conversations are not included in this transcript. -

Conference Program

September 10-12, 2008 Gas prices Utah League of Cities and Towns Debt Inflation 101st Annual Convention Insurance Cost of food What’s Asphalt Up, Housing prices Sales tax revenue What’s Down Residential construction Making Life Better At our 100th Annual Convention last September, we unveiled our “Making Life Better Campaign.” One year later, many cities and towns around the state are using it to communicate the services and events that are provided for their residents. Around the hotel you’ll see a number of banners and signs that highlight what communities around the state are doing to make life better. Check our website, ulct.org, for more information about the campaign. THANKS TO OUR CONFERENCE SPONSORS Ballard Spahr Andrews & Ingersoll, LLP Cate Equipment Company Comcast Energy Solutions Gold Cross Ambulance Intermountain Healthcare Lewis Young Robertson & Burningham, Inc. Maverick Questar Rio Tinto Rocky Mountain Power UAMPS Union Pacific Utah Local Governments Trust Zions Bank Zions Bank Public Finance Wal-Mart Waste Management of Utah General Table Information of CONTENTS Introduction . 2 All events and sessions will be held at the Sheraton City Centre with the exception President’s Message . 3 of Wednesday night’s event which will be held at The Gateway. Entertainment . 4 Please turn cell phones and audible pagers off during all meetings, workshops, general sessions, luncheons, etc. Speaker Highlights ................................................ 6 Business Session Agenda ......................................... 10 Parking: Parking at the Sheraton City Centre is free for all ULCT conference attendees and vendors. 2008 Essay Contest Winners . 11 Activities at a Glance ............................................. 12 Registration Desk Hours Sheraton City Centre Map ...................................... -

Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations

S. HRG. 114–178 Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Fiscal Year 2016 114th CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION H.R. 2578 BUREAU OF ALCOHOL, TOBACCO, FIREARMS AND EXPLOSIVES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE—OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE—OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION NONDEPARTMENTAL WITNESSES UNITED STATES MARSHALS SERVICE Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations, 2016 (H.R. 2578) S. HRG. 114–178 COMMERCE, JUSTICE, SCIENCE, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2578 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR THE DEPARTMENTS OF COM- MERCE AND JUSTICE, AND SCIENCE, AND RELATED AGENCIES FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2016, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Department of Commerce—Office of the Secretary Department of Justice—Office of the Attorney General Drug Enforcement Administration Federal Bureau of Investigation National Aeronautics and Space Administration Nondepartmental Witnesses United States Marshals Service Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/ committee.action?chamber=senate&committee=appropriations U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 93–106 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman MITCH McCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. -

The Brigham Young University Folklore of Hugh Winder Nibley: Gifted Scholar, Eccentric Professor and Latter-Day Saint Spiritual Guide

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1996 The Brigham Young University Folklore of Hugh Winder Nibley: Gifted Scholar, Eccentric Professor and Latter-Day Saint Spiritual Guide Jane D. Brady Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Folklore Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Brady, Jane D., "The Brigham Young University Folklore of Hugh Winder Nibley: Gifted Scholar, Eccentric Professor and Latter-Day Saint Spiritual Guide" (1996). Theses and Dissertations. 4548. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4548 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. the brigham young university folklore of hugh winder nibley gifted scholar eccentric professor and latterlatterdayday saint spiritual guide A thesis presented to the department of english brigham young university in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree master ofarts by jane D brady august 1996 this thesis by jane D brady is accepted in its present form by the department of english brighamofofbrigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of master of arts eq A 71i feicr f william A wilson committee chair n camCAycayalkeralker chmmioe member richad H cracroftcracrofCracrof