American Music Research Center Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Far Horizon

The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Danny Wool, Lorna Hanrahan, Mary Musser, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team THE FAR HORIZON BY LUCAS MALET (MRS. MARY ST. LEGER HARRISON) BY THE SAME AUTHOR _The Wages of Sin_ _A Counsel of Perfection_ page 1 / 464 _Colonel Enderby's Wife_ _Little Peter_ _The Carissima_ _The Gateless Barrier_ _The History of Sir Richard Calmady_ "Ask for the Old Paths, where is the Good Way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest."--JEREMIAS. "The good man is the bad man's teacher; the bad man is the material upon which the good man works. If the one does not value his teacher, if the other does not love his material, then despite their sagacity they must go far astray. This is a mystery of great import."--FROM THE SAYINGS OF LAO-TZU. ..."Cherchons a voir les choses comme elles sont, et ne voulons pas avoir plus d'esprit que le bon Dieu! Autrefois on croyait que la canne a sucre seule donnait le sucre, on en tire a peu pres de tout maintenant. Il est de meme de la poesie. Extrayons-la de n'importe quoi, car elle git en page 2 / 464 tout et partout. Pas un atome de matiere qui ne contienne pas la poesie. Et habituons-nous a considerer le monde comme un oeuvre d'art, dont il faut reproduire les procedees dans nos oeuvres."--GUSTAVE FLAUBERT. CHAPTER I Dominic Iglesias stood watching while the lingering June twilight darkened into night. -

Tauthe the Literary and Visual Art Journal of Lourdes University 2015

Tauthe the literary and visual art journal of Lourdes University 2015 1 theTau 2015 Award Winning Cover Art: Sebastian ~ by Laura Ott 2 theTau 2015 2015 Editor: Shawna Rushford-Spence, Ph.D. Layout & Design: Carla Leow, B.F.A. © Lourdes University theTau 2015 3 Acknowledgements Our sincere thanks to the following people and organizations whose generous support made publishing this journal possible: Department of English Literati Orbis Ars University Relations for Layout and Design Printing Graphics Thank you to the judges who generously gave of their time and made the difficult decisions on more than 200 submissions. Stephen Carl Veronica Lark Isabella Valentin www.lourdes.edu/TAU2015 Individual authors retain copyrights of individual pieces. No part of this text may be used without specific permission of the writer, the artist, or the University. 4 theTau 2015 Lourdes is a Franciscan University that values community as a mainstay of its Mission and Ministry. theTau 2015 5 “We read fine things but never feel them to the full until we have gone the same steps as the author” ~ John Keats The world in which we live is full of beauty, elegance, and joy, interlaced with sadness, fear, and hostility. Because we see the world through different eyes, each and every one of us, our experiences and sense of that which exists around us, are perceived individually. The purpose of The Tau is to explore the intellect of those who wish to share his or her personal experience of that world. This unique literary magazine gives our community the opportunity to reflect, spiritually, intellectually, and physically, the knowledge gained through education and the limitless perspectives that pour out from personal reflection. -

Spinal Cord Injury

Resources Offered by the MSKTC To Support Individuals Living With Spinal Cord Injury Edition 6 August 2020 www.MSKTC.org/SCI Resources Offered by the MSKTC To Support Individuals Living With Spinal Cord Injury Edition 6 August 2020 This document may be reproduced and distributed freely. The contents of this document were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0082). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this document do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center American Institutes for Research 1400 Crystal Drive, 10th Floor Arlington, VA 22202-3231 www.MSKTC.org [email protected] Phone: 202-403-5600 TTY: 877-334-3499 Connect with us on Facebook: Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems Twitter: SCI_MS About the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center The Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC) summarizes research, identifies health information needs, and develops information resources to support the Model Systems programs in meeting the needs of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and burn injury (Burn). The health information offered through the MSKTC is not meant to replace the advice from a medical professional. Users should consult their health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The current MSKTC cycle is operated by American Institutes for Research® (AIR®) in collaboration with the Center for Chronic Illness and Disability at George Mason University, BrainLine at WETA, University of Alabama, Inova, and American Association of People with Disabilities. -

Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and the Appropriation of Huayan Thought

Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and the Appropriation of Huayan Thought A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 King Pong Chiu School of Arts, Languages and Cultures TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 List of Figures and Tables 4 List of Abbreviations 5 Abstract 7 Declaration and Copyright Statement 8 A Note on Transliteration 9 Acknowledgements 10 Chapter 1 - Research Questions, Methodology and Literature Review 11 1.1 Research Questions 11 1.2 Methodology 15 1.3 Literature Review 23 1.3.1 Historical Context 23 1.3.2 Thomé H. Fang and Huayan Thought 29 1.3.3 Tang Junyi and Huayan Thought 31 Chapter 2 – The Historical Context of Modern Confucian Thinkers’ Appropriations of Buddhist Ideas 33 2.1 ‘Ti ’ and ‘Yong ’ as a Theoretical Framework 33 2.2 Western Challenge and Chinese Response - An Overview 35 2.2.1 Declining Status of Confucianism since the Mid-Nineteenth Century 38 2.2.2 ‘Scientism’ as a Western Challenge in Early Twentieth Century China 44 2.2.3 Searching New Sources for Cultural Transformation as Chinese Response 49 2.3 Confucian Thinkers’ Appropriations of Buddhist Thought - An Overview 53 2.4 Classical Huayan Thought and its Modern Development 62 2.4.1 Brief History of the Huayan School in the Tang Dynasty 62 2.4.2 Foundation of Huayan Thought 65 2.4.3 Key Concepts of Huayan Thought 70 2.4.4 Modern Development of the Huayan School 82 2.5 Fang and Tang as Models of ‘Chinese Hermeneutics’- Preliminary Discussion 83 Chapter 3 - Thomé H. -

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Meet Me in the Land of Hope and Dreams Influences of the Protest Song Tradition on the Recent Work of Bruce Springsteen (1995-2012)

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Meet me in the Land of Hope and Dreams Influences of the protest song tradition on the recent work of Bruce Springsteen (1995-2012) Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Debora Van Durme fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Nederlands- Engels” by Michiel Vaernewyck May 2014 Word of thanks The completion of this master dissertation would not have been possible without the help of several people that have accompanied me on this road. First of all, thank you to my loving parents for their support throughout the years. While my father encouraged me to listen to an obscure, dusty vinyl record called The River, he as well as my mother taught me the love for literature and music. Thanks for encouraging me to express myself through writing and my own music, which is a gift that money just cannot buy. Secondly, thanks to my great friends of the past few years at Ghent University, although they frequently – but not unfairly – questioned my profound passion for Bruce Springsteen. Also, thank you to my supervisor dr. Debora Van Durme who provided detailed and useful feedback to this dissertation and who had the faith to endorse this thesis topic. I hope faith will be rewarded. Last but not least, I want to thank everyone who proofread sections of this paper and I hope that they will also be inspired by what words and music can do. As always, much love to Helena, number one Croatian Bruce fan. Thanks to Phantom Dan and the Big Man, for inspiring me over and over again. -

April 2021 Volume 83 Number 6

ContownianThe News Magazine Conemaugh Township Area Middle School/High School April 2021 Volume 83 Number 6 Math Counts is not that new of a club. However, some of the older students at Conemaugh Township still may not A New Gas Station know it exists. Sara O’Connell, a junior at Conemaugh Township, recently found out about the Math Counts club. By Nicholas Grosik When asked about the club, she said, “I feel that it is a great club that allows students to compete in a subject that A new convenience store and gas station was approved they love. I think that it is a great experience for them.” by the Conemaugh Township supervisors last month. The location of the new gas station is at the Route 219 inter- New Dog Treats Business at Township section. The site will be 7,000 square feet and will offer parking for at least 25 cars. By BriElla Harnett The owner, Jim Moore, owns another gas station a few During the month of March, the Life Skills class started hundred yards away. Jim already has a liquor license, so a dog treat business. They sent order forms to all of the beer and wine can be sold at the new site. He intends to teachers at Conemaugh Township High School and sold a relocate the fuel business of his other gas station to this total of eighteen orders. Mrs. Kalfas, who is in charge of the new site. Life Skills class, said, “It is going quite well.” Township Chairman Steve Buncich said, “This will be a Last year, the Life Skills class held a weekly cafe for the really nice edition for residents of the township.” The new teachers. -

Pdf, 297.01 KB

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs. [Music continues under the dialogue, then fades out.] 00:00:05 Oliver Host Hello! I’m Oliver Wang. Wang 00:00:07 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes 00:00:10 Oliver Host Every episode, we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock. You know, an album that burns its way into our collective memory. And today, we’re gonna be letting the love rain shower down upon us. [Morgan chuckles.] To exclusively revisit the 2000 debut album Who is Jill Scott? Words and Sounds Vol. 1 by Jill Scott. 00:00:32 Music Music “Love Rain” from the album Who is Jill Scott? Words and Sounds Vol. 1 by Jill Scott. Love rain down on me, on me Down on me Love rain down on me, on me Down on me Love rain down on me, on me Down on me [Volume decreases and continues under the dialogue then fades out.] 00:00:50 Oliver Host Many of us were introduced to Jill Scott in the late nineties when The Roots rolled her out on the strength of their and Scott’s hit “You Got Me”. Even if she was taken off the eventual commercial version of the single in favor of Erykah Badu, Scott refused to stay behind the scenes. And come Y2K, we all got to bear witness to Scott in her full, resplendent glory on her debut. -

African American Sheet Music Collection, Circa 1880-1960

African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1028 Extent: 6.5 linear feet (13 boxes) and 2 oversized papers boxes (OP) Abstract: Collection of sheet music related to African American history and culture. The majority of items in the collection were performed, composed, or published by African Americans. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Printed or manuscript music in this collection that is still under copyright protection and is not in the Public Domain may not be photocopied or photographed. Researchers must provide written authorization from the copyright holder to request copies of these materials. The use of personal cameras is prohibited. Source Collected from various sources, 2005. Custodial History Some materials in this collection originally received as part of the Delilah Jackson papers. Citation [after identification of item(s)], African American sheet music collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey, October 13, 2006. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Manuscript Collection No. 1028 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. -

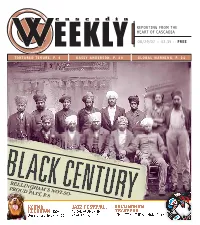

Cascadia BELLINGHAM's NOT-SO

cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA 08/29/07 :: 02.35 :: FREE TORTURED TENURE, P. 6 KASEY ANDERSON, P. 20 GLOBAL WARNING, P. 24 BELLINGHAM’S NOT-SO- PROUD PAST, P.8 HOUND JAZZ FESTIVAL: BELLINGHAM HOEDOWN: DOG AURAL ACUMEN IN TRAVERSE: DAYS OF SUMMER, P. 16 ANACORTES, P. 21 SIMULATING THE SALMON, P. 17 NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS Sustainable ] 35 UNIQUE PLANTS Communities ][ FOOD FOR NORTHWEST & land use conference 28-33 GARDENS Thursday, September 6 ornamentals, natives, fruit ][ CLASSIFIEDS ][ LANDSCAPE & 24-27 DESIGN SERVICES ][ FILM Fall Hours start Sept. 5: Wed-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 20-23 Summer: Wed-Sat 10-5 , Goodwin Road, Everson Join Sustainable Connections to learn from key ][ MUSIC ][ www.cloudmountainfarm.com stakeholders from remarkable Cascadia Region 19 development featuring: ][ ART ][ Brownfields Urban waterfronts 18 Modern Furniture Fans in Washington &Canada Urban villages Urban growth areas (we deliver direct to you!) LIVE MUSIC Rural development Farmland preservation ][ ON STAGE ][ Thurs. & Sat. at 8 p.m. In addition, special hands on work sessions will present 17 the opportunity to get updates on, and provide feedback to, local plans and projects. ][ GET ][ OUT details & agenda: www.SustainableConnections.org 16 Queen bed Visit us for ROCK $699 BOTTOM Prices on Home Furnishings ][ WORDS & COMMUNITY WORDS & ][ 8-15 ][ CURRENTS We will From 6-7 CRUSH $699 Anyone’s Prices ][ VIEWS ][ on 4-5 ][ MAIL 3 DO IT IT DO $569 .07 29 A little out of the way… 08. But worth it. 1322 Cornwall Ave. Downtown Bellingham Striving to serve the community of Whatcom, Skagit, Island Counties & British Columbia CASCADIA WEEKLY #2.35 (Between Holly & Magnolia) 733-7900 8038 Guide Meridian (360) 354-1000 www.LeftCoastFurnishings.com Lynden, Washington www.pioneerford.net 2 *we reserve the right not to sell below our cost c .