Rey-Lynn Little Graduate Student of Journalism B.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Mahō Shōjo) Anime

Make-Up!: The Mythic Narrative and Transformation as a Mechanism for Personal and Spiritual Growth in Magical Girl (Mahō Shōjo) Anime by N’Donna Rashi Russell B.A. (Hons.), University of Victoria, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Pacific and Asian Studies ©N’Donna Russell, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Make-Up!: The Mythic Narrative and Transformation as a Mechanism for Personal and Spiritual Growth in Magical Girl (Mahō Shōjo) Anime by N’Donna Rashi Russell B.A (Hons)., University of Victoria, 2015 Supervisory Committee Dr. M. Cody Poulton, Supervisor (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) Dr. Michael Bodden, Committee Member (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) iii ABSTRACT Supervisory Committee Dr. M. Cody Poulton (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) Dr. Michael Bodden (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) The mahō shōjo or “magical girl”, genre of Japanese animation and manga has maintained a steady, prolific presence for nearly fifty years. Magical Girl series for the most part feature a female protagonist who is between the ages of nine and fourteen - not a little girl but not yet a woman. She is either born with or bestowed upon the ability to transform into a magical alter-ego and must save the world from a clear and present enemy. The magical girl must to work to balance her “normal life” – domestic obligations, educational obligations, and interpersonal relationships – with her duty to protect the world. -

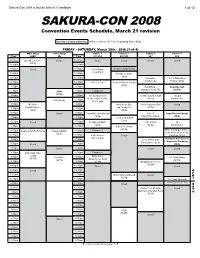

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

![Fairy Inc. Sheet Music Products List Last Updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) a \525 B \788 C \683](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1957/fairy-inc-sheet-music-products-list-last-updated-2013-03-018-price-japanese-yen-a-525-b-788-c-683-4041957.webp)

Fairy Inc. Sheet Music Products List Last Updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) a \525 B \788 C \683

Fairy inc. Sheet Music Products list Last updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) A \525 B \788 C \683 ST : Standard Version , OD : On Demand Version , OD-PS : Piano solo , OD-PV : Piano & Vocal , OD-GS : Guitar solo , OD-GV : Guitar & Vocal A Band Score Piano Guitar Title Artist Tie-up ST OD ST OD-PS OD-PV ST OD-GS OD-GV A I SHI TE RU no Sign~Watashitachi no Shochiku Distributed film "Mirai Yosouzu ~A I DREAMS COME TRUE A A A Mirai Yosouzu~ SHI TE RU no Sign~" Theme song OLIVIA a little pain - B A A A A inspi'REIRA(TRAPNEST) A Song For James ELLEGARDEN From the album "BRING YOUR BOARD!!" B a walk in the park Amuro Namie - A a Wish to the Moon Joe Hisaishi - A A~Yokatta Hana*Hana - A A Aa Superfly 13th Single A A A Aa Hatsu Koi 3B LAB.☆ - B Aa, Seishun no Hibi Yuzu - B Abakareta Sekai thee michelle gun elephant - B Abayo Courreges tact, BABY... Kishidan - B abnormalize Rin Toshite Shigure Anime"PSYCHO-PASS" Opening theme B B Acro no Oka Dir en grey - B Acropolis ELLEGARDEN From the album "ELEVEN FIRE CRACKERS" B Addicted ELLEGARDEN From the album "Pepperoni Quattro" B ASIAN KUNG-FU After Dark - B GENERATION again YUI Anime "Fullmetal Alchemist" Opening theme A B A A A A A A Again 2 Yuzu - B again×again miwa From 2nd album "guitarium" B B Ageha Cho PornoGraffitti - B Ai desita. Kan Jani Eight TBS Thursday drama 9 "Papadoru!" Theme song B B A A A Ai ga Yobu Hou e PornoGraffitti - B A A Ai Nanda V6 - A Ai no Ai no Hoshi the brilliant green - B Ai no Bakudan B'z - B Ai no Kisetsu Angela Aki NHK TV novel series "Tsubasa" Theme song A A -

2016 Conference Program

Midwest Popular Culture Association and Midwest American Culture Association Annual Conference MPCA/ACA website: http://www.mpcaaca.org #mpca16 DELETE THIS PAGE 2 Midwest Popular Culture Association and Midwest American Culture Association Annual Conference Thursday, October 6 – Sunday, October 9, 2016 Hilton Rosemont-Chicago O’Hare 5550 N River Rd Rosemont, IL 60018 t – (847)-678-4488 MPCA/ACA website: http://www.mpcaaca.org #mpca16 Executive Secretary: Kathleen M. Turner, Communication, Aurora University, Aurora, IL 60506, [email protected] Conference Coordinator: Lori Abels Scharenbroich, Crosslake, MN, [email protected] Webmaster: Matthew Kneller, Communication, Aurora University, [email protected] Program Book Editors: [email protected] Pamela Wicks, Communication, Aurora University Anne Canavan, English, Salt Lake Community College Sarah Petrovic, English, Emmanuel College 3 REGISTRATION The Registration Desk will be located in Lindberg. Hours are as follows. Thursday, October 6, 7: 00 – 11:30 a.m. & 1:00 – 6:30 p.m. Friday, October 7, 7: 00 – 11:30 a.m. & 1:00 – 6:30 p.m. Saturday, October 8, 7:00 – 11:30 a.m. & 1:00 – 6:30 p.m. Sunday, October 9, 7:00 a.m. – 2:45 p.m. The following items will be available at the Registration Desk: badges, receipts, program booklets, and late changes to program booklet. For those who did not preregister, on-site registration is $195 (including $70 membership fee). For students, retired, and unemployed, on-site registration is $185 (including $65 membership fee). Student ID must be presented. All attendees must pay both the registration fee and the membership fee. Badges must be worn at all conference events. -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi -

La Liste Des Mangas Animés

La liste des mangas animés # 009-1 Eng Sub 17 07-Ghost Fre Sub 372 11eyes Fre Sub 460 30-sai no Hoken Taiiku Eng Sub 484 6 Angels Fre Sub 227 801 T.T.S. Airbats Fre Sub 228 .hack//SIGN Fre Sub 118 .hack//SIGN : Bangai-hen Fre Sub 118 .hack//Unison Fre Sub 118 .hack//Liminality Fre Sub 118 .hack//Gift Fre Sub 118 .hack//Legend of Twilight Fre Sub 118 .hack//Roots Fre Sub 118 .hack//G.U. Returner Fre Sub 119 .hack//G.U. Trilogy Fre Sub 120 .hack//G.U. Terminal Disc Fre Sub .hack//Quantum Fre Sub 441 .hack//Sekai no mukou ni Fre Sub _Summer Fre Sub 286 A A Little Snow Fairy Sugar Fre Sub 100 A Little Snow Fairy Sugar Summer Special Fre Sub 101 A-Channel Eng Sub 485 Abenobashi Fre Sub 48 Accel World Eng Sub Accel World: Ginyoku no kakusei Eng Sub Acchi kocchi Eng Sub Ace wo Nerae! Eng Sub Afro Samurai Fre Sub 76 Afro Samurai Resurrection Fre Sub 408 Ah! My Goddess - Itsumo Futari de Fre Sub 470 Ah! My Goddess le Film DVD Ah! My Goddess OAV DVD Ah! My Goddess TV (2 saisons) Fre Sub 28 Ah! My Mini Goddess TV DVD Ai Mai! Moe Can Change! Eng Sub Ai Yori Aoshi Eng Sub Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Eng Sub Aika Eng Sub 75 AIKa R-16 - Virgin Mission Eng Sub 425 AIKa Zero Fre Sub 412 AIKa Zero OVA Picture Drama Fre Sub 459 Air Gear Fre Sub 27 Air Gear - Kuro no Hane to Nemuri no Mori - Break on the Sky Eng Sub 486 Air Master Fre Sub 47 AIR TV Fre Sub 277 Aishiteruze Baby Eng Sub 25 Ajimu - Kaigan Monogatari Fre Sub 194 Aiura Fre Sub Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka Fre Sub 387 Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka Hardcore Fre Sub AKB0048 Fre Sub Akikan! Eng Sub 344 Akira Fre Sub 26 Allison to Lillia Eng Sub 172 Amaenaide Yo! Fre Sub 23 Amaenaide Yo! Katsu!! Fre Sub 24 Amagami SS Fre Sub 457 Amagami SS (OAV) Eng Sub Amagami SS+ Plus Fre Sub Amatsuki Eng Sub 308 Amazing Nurse Nanako Fre Sub 77 Angel Beats! Fre Sub 448 Angel Heart Fre Sub 22 Angel Links Eng Sub 46 Angel's Tail Fre Sub 237 Angel's Tail OAV Fre Sub 237 Angel's Tail 2 Eng Sub 318 Animation Runner Kuromi 2 Eng Sub 253 Ankoku Shinwa Eng Sub Ano hi mita hana no namae o bokutachi wa mada shiranai. -

Filmoteka.V1.5.2008

█████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ ████████████████████████████████████████████ Filmotéka / Archiv ███████████████ ██████ 10.07.08 █████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ ██████ Anime / Hentai █████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ .hack//Liminality 0104 (OVA AHQ) .hack//G.U. Trilogy (Movie LuPerry) .hack//GIFT (OVA BA) .hack//Legend of the Twilight (BA) .hack//SIGN 0128 (TV Series AHQ) 3x3 Eyes 0107 (OVA a4e) 5 Centimeters Per Second (Movie COR) 5 Centimeters Per Second (Movie SuHi) 8 Men After (Movie RAX) 1001 Nights (Movie niizk) A.D. Police 0103 (OVA ILA) A.D. Police 0112 (TV Series AHQ) Aachi And Ssipak (Movie KAA) Aachi.And.Ssipak.DVDRip.XviDPosTX (Movie) Abashiri Family 0104 (OVA HD) Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai 0113 (TV Series KAA) AfroKen (OVA AClassic) Afro Samurai 0105 (OVA daijoubu) Afro Samurai 0105 (OVA SAR) Afro.Samurai.E0105.DVDRip.XviDSiNK (OVA) Agent AiKa 0107 (OVA AnimeTakeover) AIKa R16: Virgin Mission 0103 (OVA PFSub) Aim For The Ace! 0116?? (TV Series ILA) Aim For The Best! (Movie ILA) Aim For The Top! Gunbuster & Science 0112 (OVA KAA) Akane Maniax 0103 (OVA al) Akira (Movie as) Akira (Movie COR) Akira (Movie Jarudin) Akira (Movie niizk) Akira (Movie zx) Akira.1988.iNTERNAL.DVDRip.XviDiLS (Movie) Akira.1988.REMASTERED.THX.DVDRip.x264R55 (Movie) Alibaba and the Forty Theives (Movie) Alice (OVA ILA) Amon Saga (OVA a4e) Anal Sanctuary 0102 (OVA KH) Ancient Book Of YS 0107 -

Ohjelmakartta

MYYNTIOSASTOLTAMME UUTUUDET JA AIEMMIN ILMESTYNEET MANGAT! Sisällys V for Victory MYYNTIOSASTOLTAMME UUTUUDET IETOA JA OHJEITA Paljon onnea vaan! Desucon täyttää tämän T ....................4 tapahtuman myötä jo 5 vuotta! Ohimennen heitetystä ajatuksesta on kasvanut neljän vuotuisen JÄRJESTYSSÄÄNNÖT ..................5 desutapahtuman - Desuconin, Desucon Frostbiten, JA AIEMMIN ILMESTYNEET MANGAT! DesuTalksin ja DesuCruisen - yhteenliittymä. LTABILEET Samankaltaisuuksista huolimatta jokainen I ...............................6 tapahtumista on selkeästi oma kokonaisuutensa. Tämänkesäinen Desucon on vuorossaan jo 12. KUNNIAVIERAAT ........................7 desutapahtuma! OSPLAY ESUCONISSA Aivan vahingossa emme ole näin pitkälle päässeet C D .............9 vaan taustalta löytyy huikea määrä työtä, sattumuksia ja onnistumisia. Kuvia ja kertomuksia CONISSA TAPAHTUU ..................10 matkan varrelta löytyy perjantaina Metsähallin 2. parvelta kokoamastamme Desunäyttelystä, ja koko ISUAL UEST viikonlopun Metsähallissa pyörivältä DesuScreeniltä. V Q .........................12 Käy tutustumassa ja näe, miten Desucon on vuosien mittaan kehittynyt ja kasvanut! OHJELMAKARttA ......................16 Vaikka Desuconia on tehty jo viisi vuotta, on siinä AFÉ CHIGO silti parantamisen ja kehittämisen varaa. Tälläkin C I ............................18 kertaa muutoksia edellisestä conista on tapahtunut - esimerkiksi iltabileet muuttivat uusiin, suurempiin LAHDEN KARttA .......................21 tiloihin - ja lukemalla tämän ohjelmalehden huolella varmistat, -

07-Ghost 100 Byou Cinema: Robo to Shoujo (Kari) 1001 Nights 2001 Ya

07-Ghost Akazukin Chacha 100 Byou Cinema: Robo to Shoujo (Kari) Akazukin Chacha 1001 Nights Akazukin Chacha (1995) 2001 Ya Monogatari Akihabara Dennou-gumi Space Fantasia 2001 Ya Monogatari Alien 9 3x3 Eyes Akihabara Dennou-gumi 3x3 Eyes Seima Densetsu Akihabara Dennou-gumi: 2011 Nen no Natsuyasumi 5-tou ni Naritai. Allison to Lillia Alps no Shoujo Heidi Alps no Shoujo Heidi (1979) A Channel Alps no Shoujo Heidi: Alm no Yama Hen A Channel: The Animation Alps no Shoujo Heidi: Heidi to Clara Hen A Channel +Smile Amaenaide yo!! Aa! Megami-sama! Amaenaide yo!! Aa! Megami-sama! Amaenaide yo!! Katsu!! Aa! Megami-sama! Chicchaitte Koto wa Benri Da ne! Amagami SS Gekijouban Aa! Megami-sama! Amagami SS Aa! Megami-sama! Sorezore no Tsubasa Amagami SS Plus Aa! Megami-sama! Tatakau Tsubasa Amatsuki Aa! Megami-sama! (2011) Andersen Douwa: Ningyo Hime Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai Android Ana Maico 2010 Accel World OVA Angel Densetsu Acchi Kocchi Angelique Ace o Nerae! Angelique: Shiroi Tsubasa no Memoire Ace o Nerae! Angelique Ace o Nerae! (1979) Koisuru Tenshi Angelique: Kokoro no Mezameru Toki Agatha Christie no Meitantei Poirot to Marple Koisuru Tenshi Angelique: Kagayaki no Ashita Ai Monogatari: 9 Love Stories Neo Angelique Abyss Ai no Kusabi (2012) Neo Angelique Abyss: Second Age Ai Shoujo Pollyanna Story Animation Seisaku Shinkou Kuromi-chan Ai Tenshi Densetsu Wedding Peach Animation Seisaku Shinkou Kuromi-chan Ai Tenshi Densetsu Wedding Peach Animation Seisaku Shinkou Kuromi-chan 2 Ai Tenshi Densetsu Wedding Peach DX Anime Classic Collection Ai yori Aoshi Anime Sanjuushi - Aramis no Bouken Ai yori Aoshi Anime Tenchou Ai yori Aoshi: Enishi Anju to Zushiou Maru Air Anne Frank Monogatari Gekijouban Air Anne no Nikki Air Gear: Kuro no Hane to Nemuri no Mori - Break on the Ano Hi Mita Hana no Namae o Bokutachi wa Mada Sky Shiranai. -

Hataraki Man Anime Download

Hataraki man anime download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Apr 22, · Alternate Titles: 働きマン, Hataraki Man, ['Working Man'] Genre: Comedy, Drama, Romance, Seinen, Slice of Life, Sub Type: TV(Fall ) Status: Finished Airing Number of Episodes: 11 Episode(s) Views: Views Date: Oct 13, to Dec 22, [MyAnimeList] Score: Summary: Sypnosis: Hiroko Matsukata is a woman who works for a magazine company.. She puts all she has . Watch Hataraki Man HD anime online for free. Free download HD anime with English subbed, dubbed. Best alternatives to GoGoAnime. Download File Hataraki Man Episode mp4. © SandUP - All Rights Reserved. Download File Hataraki Man Episode mp4. Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. HATARAKI MAN. Type: TV Series. Plot Summary: Hiroko Matsukata is a woman who works for a magazine company. She puts all she has into her work, and is known as a strong, straight-forward working girl, who can at will turn herself into Hataraki man (working man) mode. Despite Hiroko’s success at work, her life lacks romance. Hataraki Man Episodio 2; Comentario. Publicidade. Publicidade. Publicidade. Muito Hentai - Assistir Videos de Sexo - Mangas Eroticos - Hentai - Super Animes - Free Hentai Stream - Watch Hentai in English. Super Animes Online - O melhor site para assistir anime . The following Hataraki Man Episode 11 English SUB has been released. Dramacool will always be the first to have the episode so please Bookmark and add us on Facebook for update!!! Enjoy. Oct 13, · Hataraki Man was an anime that caught me by surprise. The anime deals with themes of work, overwork, dissatisfaction with work, finding your purpose in work, ultimately loving your job, and even death. -

Newsletter 01/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 01/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 198 - Januar 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 01/07 (Nr. 198) Januar 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, erotischer Natur, so floriert das Geschäft dem HD DVD Lager anzuschließen. So liebe Filmfreunde! dort mit harter Kost schon seit Jahren na- sollen in den kommenden Wochen bereits Auch die schönste Zeit geht einmal zu hezu ungebremst. Die Anzahl der in den die ersten freizügigen HD DVDs auf den Ende. Gemeint sind damit natürlich die USA auf DVD veröffentlichten Hardcore- Markt kommen, darunter der von Joone zwei Wochen Betriebsruhe ”zwischen den Filmen dürfte genauso groß sein wie die selbst inszenierte Hardcore-Blockbuster Jahren”, die wir uns traditionell selbst Veröffentlichungen in allen anderen Gen- PIRATES. Sonys Entscheidung zum Nein verschrieben haben. Pech also für uns, res. Wer also könnte noch ernsthaft an der für Hardcore-Produkte auf Blu-ray Disc dass wir jetzt schon wieder Mitte Januar wirtschaftlichen Wichtigkeit solcher Pro- könnte somit auf längere Sicht zum Aus haben, obgleich 2007 doch eigentlich gera- duktionen zweifeln? Egal welches Heim- für Blu-ray führen - vollkommen unabhän- de erst angefangen hat. Aber das liegt ver- kinomedium von der Industrie auf die gig davon, ob es vielleicht die bessere HD- mutlich an der etwas verzerrten Wahrneh- Konsumenten losgelassen wurde, die Technik ist oder nicht. Denn letztendlich mung der Zeit, die sich mit zunehmendem Pornoindustrie war stets eine der Ersten, zählen für die Konsumenten nur die ver- Alter einstellt. -

Tezuka Osamu, Founder of Story Manga

ISSN 1349-5860 Contents High School Students Photo Collection Published Japanese Culture Now Manga: In early July TJF published tion is laid out like a magazine, bringing to read- Japan’s Favorite The Way We Are 2006 (in ers the hopes and dreams as well as worries and Entertainment Japanese; A4 size, 64 pages, woes of high school students just as they are. Media 3,000 copies), a collection Ninety works from The Way We Are photo of the prize-winning works collections can be viewed at the English website Meeting People from the Tenth Annual “The Way We Are: Photo Essays of High School Never Give Up! Photo and Message Con- Students in Japan.” Two easy-to-understand test. With the appearance rewrite versions of the Japanese captions and Access This Page! of this photo collection, the annual photo con- essays (one with and the other without yomi- “Tsunagaaru” to Open test program held since 1997 comes to a close. gana readings) are also provided for language Autumn 2007 This final collection features an 8-page color learners. Moreover, where necessary, footnotes retrospect commemorating the ten years of the and links to explanatory photos and in-depth The Way We Are 2006 contest with memorable photographs and a explanations are appended to the English trans- (Japanese edition): chronology listing the major events, key words, lations. For some photos, visitors can also listen Free copy to and trends for each year. As before, the collec- to an audio recording. the first 100 applicants Send an e-mail with your Manga to Be Used for Japanese-language Textbooks full name, delivery address (including country), and affiliated school to: TJF cooperates in the production first for Japanese language textbooks in China.