From Bauhaus to M- the Trajectories of the Ready-Made in Art and [H]Ouse: the Concept Prototypes for Prefabricated Architecture Intersect During the Modern Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chassis Design for SAE Racer

University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Engineering and Surveying Chassis Design for SAE Racer A dissertation submitted by: Anthony M O’Neill In fulfilment of the requirements of ENG 4111/2 Research Project Towards the degree of Bachelor of Engineering (Mechanical) Submitted: October 2005 1 Abstract This dissertation concerns the design and construction of a chassis for the Formula SAE-Aust race vehicle – to be entered by the Motorsport Team of the University of Southern Queensland. The chassis chosen was the space frame – this was selected over the platform and unitary styles due to ease of manufacture, strength, reliability and cost. A platform chassis can be very strong, but at the penalty of excessive weight. The unitary chassis / body is very expensive to set up, and is generally used for large production runs or Formula 1 style vehicles. The space frame is simple to design and easy to fabricate – requiring only the skills and equipment found in a normal small engineering / welding workshop. The choice of material from which to make the space frame was from plain low carbon steel, AISI-SAE 4130 (‘chrome-moly’) or aluminium. The aluminium, though light, suffered from potential fatigue problems, and required precise heat / aging treatment after welding. The SAE 4130, though strong, is very expensive and also required proper heat treatment after welding, lest the joints be brittle. The plain low carbon steel met the structural requirements, did not need any heat treatments, and had the very real benefits of a low price and ready availability. It was also very economical to purchase in ERW (electric resistance welded) form, though CDS (cold drawn seamless) or DOM (drawn over mandrel) would have been preferable – though, unfortunately, much more expensive. -

Structural Design of a Geodesic-Inspired Structure for Oculus: Solar Decathlon Africa 2019

Structural Design of a Geodesic-inspired Structure for Oculus: Solar Decathlon Africa 2019 A Major Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Submitted By: Sara Cardona Mary Sheehan Alana Sher December 14, 2018 Submitted To: Tahar El-Korchi Nima Rahbar Steven Van Dessel Abstract The goal of this project was to create the structural design for a lightweight dome frame structure for the 2019 Solar Decathlon Africa competition in Morocco. The design consisted of developing member sizes and joint connections using both wood and steel. In order to create an innovative and competitive design we incorporated local construction materials and Moroccan architectural features. The result was a structure that would be a model for geodesic inspired homes that are adaptable and incorporate sustainable features. ii Acknowledgements Sincere thanks to our advisors Professors Tahar El-Korchi, Nima Rahbar, and Steven Van Dessel for providing us with feedback throughout our project process. Thank you to Professor Leonard Albano for assisting us with steel design and joint design calculations. Additionally, thank you to Kenza El-Korchi, a visiting student from Morocco, for helping with project coordination. iii Authorship This written report, as well as the design development process, was a collaborative effort. All team members, Sara Cardona, Mary Sheehan, and Alana Sher contributed equal efforts to this project. iv Capstone Design Statement This Major Qualifying Project (MQP) investigated the structural design of a lightweight geodesic-dome inspired structure for the Solar Decathlon Africa 2019 competition. The main design components of this project included: member sizing and verification using a steel and wood buckling analysis, and joint sizing using shear and bearing analysis. -

Design Method for Adaptive Daylight Systems for Buildings Covered by Large (Span) Roofs

Design method for adaptive daylight systems for buildings covered by large (span) roofs Citation for published version (APA): Heinzelmann, F. (2018). Design method for adaptive daylight systems for buildings covered by large (span) roofs. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Published: 12/06/2018 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Now on View in the Entrance of Art Los Angeles Contemporary, Ramada Santa Monica Is the Fourth Iteration in Mark Hagen's Serie

Now on view in the entrance of Art Los Angeles Contemporary, Ramada Santa Monica is the fourth iteration in Mark Hagen’s series of space frame installations—this time housing the catalog of materials from independent publisher Artbook | D.A.P. Aluminum triangles join into modular architectural units, towering floor to ceiling and enclosing a corner of the lobby, where polished fossils (in fact fossilized feces) act as bookends. We've seen the future and we're not going titles Hagen’s 2012 space frame work, that one affixed with rough slabs of obsidian. The pleasure of this uneasy pairing springs from its clever twinning of aesthetics and eras of technology: the irregular cuts of obsidian with the uniformity of the space frame, the material of prehistoric weaponry with the template for 1950s modular design. We’ve seen the future and we’re not going both rejects technological accelerationism and admits a melancholic truth: our utopian techno-future simply has not come. This ambivalence about technology, the failure of positivism to deliver on its promises, animates Hagen’s space frame sculptures, as they call out to (and become implicated in) the sinister evolution of the form. In the middle of the twentieth century, space frames were perfected by utopian architect Buckminster Fuller in his geodesic domes. Now, luxury car manufactures including Audi and Lamborghini advertise their use of the space frame, testifying to the recherché design. This evolution is unsurprising. Buckminster Fuller’s ideals of totalizing efficiency as well as neologisms like “synergy” find exquisite expression in corporate management; the hippie communes founded on his principles collapsed within the decade. -

Review on Study of Space Frame Structure System

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 07 Issue: 04 | Apr 2020 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Review on Study of Space Frame Structure System S. A. Ashtul1, S. N. Patil2 1PG Student, Department of Civil Engineering 2Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Rajarambapu Institute of Technology, Maharashtra, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***---------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - In the last few decades there was continuous these techniques concrete slab over the top chord which development in the construction industry. Mankind is always enhances the compression capacity and shows better attempted to utilize the maximum space for the structure. The performance of space frame structure [10]. need for modern structures is to achieve a large clear span The present paper focuses on the basic concept of a space with the economy. Now-days it is observed that there is a frame system. And also on the studies carried out by several growing interest in space frame systems. A space frame is a 3D researchers for understanding the structural behavior of the structural system in which well-organized linear axial space frame system by considering various parameters. elements are put together for the uniform distribution of forces. The main purpose to use these systems is to cover a large span area and giving a pleasant appearance to the 2. SPACE FRAME SYSTEM structure. Also, the space frames are light in weight and can easily be transported to the site. The objective of this paper is 2.1 Introduction to present the detailed concept of space frame systems and applications of these systems. -

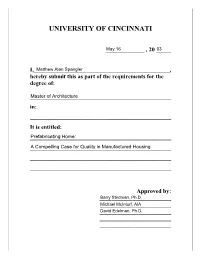

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Prefabricating Home A Compelling Case for Quality in Manufactured Housing A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture A presentation of research conducted in the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning. May, 2003 by Matthew A. Spangler Bachelor of Science in Architecture, University of Cincinnati, 2001 Committee: Barry Stedman, Ph.D., Chair Michael McInturf, AIA David Edelman, Ph.D. Abstract Statement of Purpose The mobile home evolved as a low-cost alternative to site-built housing from the fusion of prefabricated housing systems and travel trailers. Low-income families adopted it as a viable form of affordable home ownership, and for several decades manufactured housing remained dedicated to this market. Twenty years ago the design -

Modern Methods of Construction

Modern methods of construction The NHBC Foundation Expert Panel Building on experience The NHBC Foundation’s research programme is guided by the following panel of senior representatives from the industry: This guide, prepared by Studio Partington, explores the paradox: if the arguments for Rt. Hon. Nick Raynsford Andrew Day Geoff Pearce houses to be manufactured like cars are so Chairman of the NHBC Foundation Head of Sustainability, Executive Director of Regeneration compelling, why is factory-built housing not and Expert Panel Telford Homes plc and Development, more common? It investigates notable periods Swan Housing Association of innovation in house building and looks at Tony Battle Russell Denness Joint Managing Director, Group Chief Executive, Gwyn Thomas elements of design as well as the social and Kind & Co Croudace Homes Group Head of Housing and Policy, economic influences that drive change. The BRE Trust guide charts the progression of innovation in Jane Briginshaw Michael Finn Steve Turner timber, steel and concrete and considers the Design and Sustainability Design and Technical Director, Consultant, Jane Briginshaw Barratt Developments plc Head of Communications, benefits and risks associated with different and Associates Home Builders Federation forms of construction. Cliff Fudge Andrew Burke Technical Director, H+H UK Ltd Andy von Bradsky By interrogating past failures as well as Development Director, Design and Delivery Advisor, The Housing Forum Ministry of Housing, Communities commending high quality design, this guide -

The Prefabricated Home

The Prefabricated Home Colin Davies reaktion books The Prefabricated Home The Prefabricated Home Colin Davies REAKTION BOOKS Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 79 Farringdon Road London EC1M 3JU, UK www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2005, reprinted 2005 Copyright © 2005 Colin Davies All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Davies, Colin The prefabricated home 1. Prefabricated houses 2. Architecture, Domestic – 20th century 3. Buildings, Prefabricated 4. Architecture, Modern – 20th century I. Title 728.3'7'09045 ISBN 1 86189 243 8 Contents Introduction 7 PART I: HISTORIES 1. An architectural history 11 2. A non-architectural history 44 3. House of the century: the mobile home 69 PART II: THEORIES 4. The question of authorship 88 5. Professionalism and pattern books 107 6. Down with the system 130 PART III: PRACTICES 7. Ideal homes 148 8. Little boxes 169 9. The robot and the carpenter 186 Conclusion 202 References 209 Bibliography 214 Acknowledgements 216 Index 217 When I was younger It was plain to me I must make something of myself. Older now I walk back streets Admiring the houses Oftheverypoor... from Pastoral by William Carlos Williams Introduction This is a book about the prefabricated house, but more importantly it is a book about modern architecture. The idea is that a study of the prefabricated house might shed light on the true nature of modern architecture and show the way forward to its much-needed reform. -

Agencement in Housing Markets: the Case of the UK Construction Industry

Edinburgh Research Explorer Agencement in housing markets: The case of the UK construction industry Citation for published version: Lovell, H & Smith, S 2010, 'Agencement in housing markets: The case of the UK construction industry', Geoforum, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 457-468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.11.015 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.11.015 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Geoforum Publisher Rights Statement: This is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive version was subsequently published in Geoforum (2010) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Agencement in Housing Markets: The Case of the UK Construction Industry Heather Lovell* and Susan J. -

House in a Box: Prefabricated Housing in the Jackson Purchase Cultural Landscape Region, 1900 to 1960

House in a Box: Prefabricated Housing in the Jackson Purchase Cultural Landscape Region, 1900 to 1960 Written and designed by Cynthia E. Johnson Rachel Kennedy, Editor All photographs by the Kentucky Heritage Council, unless otherwise noted This publication was sponsored by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet in coopera- tion with the Kentucky Heritage Council. The Kentucky Heritage Council, an agency of the Kentucky Commerce Cabinet, is the State Historic Preservation Offi ce. For more information about Heritage Council programs, please visit our website at http://www.heritage.ky.gov/ Table of Contents House in a Box: Prefabricated Housing in the Jackson Purchase Cultural Landscape Region, 1900 to 1960 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................. 4 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 5 Section I. Methodology ..................................................................................................... 9 Research Design.................................................................................................................. 9 Information Sources.......................................................................................................... 10 Issues with Fieldwork ....................................................................................................... 12 Section II. Domestic Prefabrication Historic Context ................................................ -

A Review of Prefab Home and Relevant Issues

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals A REVIEW OF PREFAB HOME AND RELEVANT ISSUES Mohammad PANJEHPOUR 1, Abang Abdullah ABANG ALI 2 1 Dr., Housing Research Centre, University Putra Malaysia, Email: [email protected] (corresponding author) 2 Professor, Housing Research Centre, University Putra Malaysia, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT REZUMAT Having an easily built house has been always one A avea o casă uşor de construit a reprezentat of human wishes. Prefabricated home makes this întotdeauna una dintre dorinţele omeneşti. Casele wish come true because of its affordability and prefabricate îndeplinesc această dorinţă, datorită fast completion. This paper gives an overview of preţului scăzut şi al execuţiei rapide. Articolul different types of prefab home and its prezintă o trecere în revistă ale diferitelor tipuri terminology. This review sheds light on the de case prefabricate şi a terminologiei aferente. characterisation of prefab home, which takes the Sunt caracterizate casele prefabricate, sub aspects of off-site technology, mass aspectul tehnologiilor industrializate, al adaptării customisation, and sustainability into pe scară largă şi al sustenabilităţii. Articolul este consideration. This paper is confined to general focalizat asupra analizei generale a caselor review of prefab home without going through prefabricate, fără a aborda diferitele sisteme different systems utilised in off-site technology. utilizate în tehnologiile industrializate. Deşi In spite of the fact that prefab home has many advantages, which are discussed in this review, it casele prefabricate au multe avantaje, care sunt suffers from a few drawbacks which should be discutate, ele au câteva neajunsuri, care trebuie considered by designers. -

Dubai: Re-Designing Labor Worker Communities

Syracuse University SURFACE School of Architecture Dissertations and Architecture Senior Theses Theses Spring 2014 Dubai: Re-Designing Labor Worker Communities Can Cakmak Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/architecture_theses Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Cakmak, Can, "Dubai: Re-Designing Labor Worker Communities" (2014). Architecture Senior Theses. 203. https://surface.syr.edu/architecture_theses/203 This Thesis, Senior is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Architecture Dissertations and Theses at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DUBAI: RE-DESIGNING LABOR WORKER COMMUNITIES Can Cakmak Syracuse University Fall 2013 Advisors: Jonathan Massey + Anne Englot CHAPTER 1: THESIS PREP ABSTRACT In an effort to provide humane living conditions for immigrant workers in Dubai who are trapped in the Most labor camps where construction workers live today exist as a rentable development designed for flawed immigration system, I will design a ‘worker community’ to replace the ‘labor camps’ where workers profit and lacking basic living amenities. In order to raise the standard of living of the workers, this thesis live today. These communities will be tested at a variety of levels, from planning, infrastructure, modularity will propose a redesign of the labor camps into worker communities, which will be located immediately to materiality; and while certain elements such as planning will play a much more significant role than, next to the construction site. The community will include amenities and public spaces, which will be built for example, infrastructure, the goal will be to generate a worker community which will provide necessary up of modular typologies based on workers’ temporalities and needs.