Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

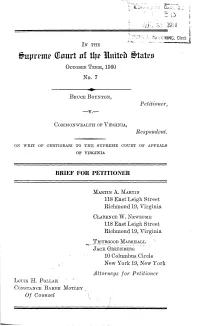

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

Everything Is a Story

EVERYTHING IS A STORY Editor Maria Antónia Lima EVERYTHING IS A STORY: CREATIVE INTERACTIONS IN ANGLO-AMERICAN STUDIES Edição: Maria Antónia Lima Capa: Special courtesy of Fundação Eugénio de Alemida Edições Húmus, Lda., 2019 End.Postal: Apartado 7081 4764-908 Ribeirão – V. N. Famalicão Tel. 926 375 305 [email protected] Printing: Papelmunde – V. N. Famalicão Legal Deposit: 000000/00 ISBN: 978-989-000-000-0 CONTENTS 7 Introduction PART I – Short Stories in English 17 “It might be better not to talk”: Reflections on the short story as a form suited to the exploration of grief Éilís Ní Dhuibhne 27 Beyond Boundaries: The Stories of Bharati Mukherjee Teresa F. A. Alves 34 The Identity of a Dying Self in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych and in Barnes’s The Story of Mats Israelson Elena Bollinger 43 And They Lived Unhappily Ever After: A. S. Byatt’s Uncanny Wonder Tales Alexandra Chieira 52 (Re)imagining Contemporary Short Stories Ana Raquel Fernandes 59 “All writers are translators of the human experience”: Intimacy, tradition and change in Samrat Upadhyay’s imaginary Margarida Pereira Martins 67 Literariness and Sausages in Lydia Davis Bernardo Manzoni Palmeirim PART II – AMERICAN CREATIVE IMAGINATIONS 77 Schoolhouse Gothic: Unsafe Spaces in American Fiction Sherry R. Truffin 96 Slow time and tragedy in Gus Van Sant’s Gerry Ana Barroso 106 American Pastoralism: Between Utopia and Reality Alice Carleto 115 Kiki Smith or Kiki Frankenstein: The artist as monster maker Maria Antónia Lima 125 Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic Revisited in André Øvredal’s -

Ch 15 the NEW DEAL

Ch 15 THE NEW DEAL AMERICA GETS BACK TO WORK SECTION 1: A NEW DEAL FIGHTS THE DEPRESSION I. Americans Get a New Deal A. The 1932 presidential election show Americans ready for change 1. Republicans re- nominated Hoover despite his low approval rating 2. The Democrats nominated Franklin D Roosevelt Election of 1932 Roosevelt Hoover ROOSEVELT WINS OVERWHELMING VICTORY a. Democrat Roosevelt, known as FDR, was a 2- term governor of NY b. reform-minded; projects friendliness, confidence B. Democrats overwhelmingly win presidency, Senate, House • Greatest Democratic victory in 80 years FDR easily won the 1932 election Election of 1932 Roosevelt’s Strengths • http://www.history.com/topics/1930s/videos #franklin-roosevelts-easy-charm C. Roosevelt’s Background 1. Distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt. Came from a wealthy New York family. 2. Wife Eleanor was a niece of Theodore Roosevelt. • Charming, persuasive. • ServeD as secretary of the navy anD New York governor. Franklin and Eleanor Franklin as a young man 3. Polio a. In 1921 Roosevelt caught polio, a crippling disease with no cure. b. Legs were paralyzed and he wore steel braces and a wheelchair later in life. Roosevelt in a wheelchair D. Inauguration (March 4, 1933) 20th Amendment =January 20, ratified Jan 23, 1933 1. Between the election and his inauguration, the Depression worsened. 2. High unemployment, more bank failures. Roosevelt Inaugural speech Roosevelt Inaugural speech "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance." The New Deal • http://www.history.com/topics/1930s/videos #the-new-deal-how-does-it-affect-us-today E. -

Historic CD Actions.Pmd

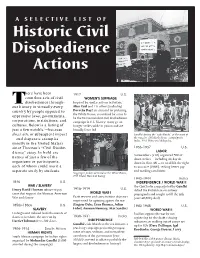

A SELECTIVE LIST OF Historic Civil Disobedience Actions here have been 1917 U.S. countless acts of civil WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE Tdisobedience through- Inspired by similar actions in Britain, out history in virtually every Alice Paul and 217 others (including country by people opposed to Dorothy Day) are arrested for picketing oppressive laws, governments, the White House, considered by some to be the first nonviolent civil disobedience corporations, institutions, and campaign in U.S. history; many go on cultures. Below is a listing of hunger strikes while in prison and are just a few notable — because brutally force-fed sheer size or subsequent impact Gandhi during the “Salt March,” at the start of the massive civil disobedience campaign in — and disparate examples India, 1930. Photo via Wikipedia. (mostly in the United States) since Thoreau’s “Civil Disobe- 1936-1937 U.S. dience” essay. In bold are LABOR names of just a few of the Autoworkers (CIO) organized 900 sit- down strikes — including 44-day sit- organizers or participants, down in Flint, MI — to establish the right each of whom could merit a to unionize (UAW), seeking better pay separate study by students. and working conditions Suggragist pickets arrested at the White House, 1917. Photo: Harris & Ewing 1940-1944 India 1846 U.S. INDEPENDENCE / WORLD WAR II WAR / SLAVERY The Quit India campaign led by Gandhi 1918-1919 U.S. Henry David Thoreau refuses to pay defied the British ban on antiwar WORLD WAR I taxes that support the Mexican-American propaganda and sought to fill the jails War and slavery Draft resisters and conscientious objectors (over 60,000 jailed) imprisoned for agitating against the war 1850s-1860s U.S. -

League Launches Advocacy Initiative by CAROLE GRAVES TML Communications Director

1-TENNESSEE TOWN & CITY/JANUARY 29, 2007 www.TML1.org 6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 58, Number 2 January 29, 2007 League launches advocacy initiative BY CAROLE GRAVES TML Communications Director The Tennessee Municipal League has launched a new advo- cacy program called “Hometown Connection.” The mission of the program is to foster better relation- ships between city officials and their legislators and enhance the League’s advocacy efforts on Capi- tol Hill. TML’s Hometown Connection will provide many resources to help city officials stay up-to-date on leg- islative activities, as well as offer more opportunities for the League’s members to become more involved in issues affecting municipalities Among the many resources at their disposal are: • Legislative Bulletins • Action Alerts • Special Committee Lists Photo by Victoria South • TML Web Site and the Home- town Connection Ceremony marks Governor Bredesen’s second term • District Directors’ Program With First Lady Andrea Conte by his side, Gov. Phil Bredesen took the oath of office for his second term as the 48th Govornor of Tennessee • Hometown Champions before members of the Tennessee General Assembly, justices of the Tennessee Supreme Court, cabinet staff, friends, family and close to 3,000 • Hometown Heroes Tennesseans. The inauguration ceremony took place on War Memorial Plaza in front of the Tennessee State Capitol. After being sworn in, • Legislative Contact Forms Bredesen delivered an uplifting 12-minute address focusing on education in Tennessee as his number one priority along with strengthening • Access to Legislators’ voting Tennessee’s families. Bredesen praised Conte as an “amazing” first lady highlighting her efforts to help abused children by treking 600 miles record on key municipal issues across Tennessee and thanked her for “32 years of love and friendship.” Entertaining performances included the Tennessee National Guard • Tennessee Town and City Band and the Tennessee School for the Blind’s choral ensemble. -

Of Steel Belted Radial Tires O£Ro Police Patro~ Car~

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. NBS Special Report on an Publication Investigation of the 480-18 High Speed aza $ of Steel Belted Radial Tires o£ro Police Patro~ Car~ ~ law Enforrcem ant I Equipment Tect"inology LOA~ DOCUMENT RETURN TO: NCJRS P. O. BOX 24036 S. W: POST OFFICE WASHINGTON, D.C. ~CD24 U.S~ DEPARTMENT Of COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards NBS Special Report on an Publscation Investigation of the 480-18 Hi Speed Hazards .il of Steel Belted Radial Tires on Police Cars by Jared J. Collard Law Enforcement Standards Laboratory Center for Consumer Product Technology National Bureau of Standards Washington, D. C. 20234 'I prepared for National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice Law Enforcement Assistance Administration U.S. Department of Justice Washington, D. C. 20531 ~Ul6 ~grl ACQUiSiTiONS Issued June 1977 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Juanita M. Kreps, Secretary Dr. Sidney Harman, Under Secretary Jordan J. Baruch, Assistant Secretary for Science and Technology NATIONA~ BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Ernest Ambler, Acting Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Collard, Jared J. Report on an investigation of the high speed hazards of steel belted radial tires on police patrol cars. (Law enforcement equipment technology) (NBS special publica tion ; 480-18) Supt. of Docs. no.: CI3.10/480:18 1. Police vehicles-Tires. 2. Tires, Rubber-Standards. I. National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. n. Law Enforce ment Standards Laboratory. III. Title: Report on an investigation of the high speed hazards of steel belted radial tires. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT AND FREEDOM RIDES 1961 By: Angelica Narvaez Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott vCharles Hamilton Houston, an African-American lawyer, challenged lynching, segregated public schools, and segregated transportation vIn 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses, but gained it little attention vIn 1953, a bus boycott in Baton Rouge partially integrated city buses vWomen’s Political Council (WPC) v An organization comprised of African-American women led by Jo Ann Robinson v Failed to change bus companies' segregation policies when meeting with city officials Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) vVirginia's law allowed bus companies to establish segregated seating in their buses vDuring 1944, Irene Morgan was ordered to sit at the back of a Greyhound Bus v Refused and was arrested v Refused to pay the fine vNAACP lawyers William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall contested the constitutionality of segregated transportation v Claimed that Commerce Clause of Article 1 made it illegal v Relatively new tactic to argue segregation with the commerce clause instead of the 14th Amendment v Did not claim the usual “states rights” argument Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) v Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law v Deemed segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional v “Found that Virginia's law clearly interfered with interstate commerce by making it necessary for carriers to establish different rules depending on which state line their vehicles crossed” v Made little -

Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the Images of Their Movements

MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ, AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by ANDREA SHAN JOHNSON Dr. Robert Weems, Jr., Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2006 © Copyright by Andrea Shan Johnson 2006 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS Presented by Andrea Shan Johnson A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________________ Professor Robert Weems, Jr. __________________________________________________________ Professor Catherine Rymph __________________________________________________________ Professor Jeffery Pasley __________________________________________________________ Professor Abdullahi Ibrahim ___________________________________________________________ Professor Peggy Placier ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to many people for helping me in the completion of this dissertation. Thanks go first to my advisor, Dr. Robert Weems, Jr. of the History Department of the University of Missouri- Columbia, for his advice and guidance. I also owe thanks to the rest of my committee, Dr. Catherine Rymph, Dr. Jeff Pasley, Dr. Abdullahi Ibrahim, and Dr. Peggy Placier. Similarly, I am grateful for my Master’s thesis committee at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, Dr. Annie Gilbert Coleman, Dr. Nancy Robertson, and Dr. Michael Snodgrass, who suggested that I might undertake this project. I would also like to thank the staff at several institutions where I completed research. -

Building Racial Bridges: Why We Can't Wait by Martin Luther King, Jr

Building Racial Bridges: Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King, Jr. February 2, 2016 Discussion led by Collin College Professor Michael Phillips Background information: “Jim Crow” was a character in the minstrel shows where white entertainers would blacken their faces and perform satirical reviews of current events as if they were African Americans. The Jim Crow Laws came to set the boundaries of segregation. Racial separation rose after slavery and became legal in the 1880’s. At that time poor whites had the distinction of never being someone’s property, bought or sold, or families separated. With the 13th (abolishing slavery), 14th (giving blacks citizenship), and 15th (giving blacks voting rights) amendments being passed, poor whites became discontent. They had no distinctive rights over the Negro. Populism, a radical movement working for justice and equal rights for all, rose in the 1880’s and ‘90’s. It involved the support of both black and white farmers working together toward economic justice and represented a threat to the Southern economic power structure. Two types of segregation: De jure – by law, evident in the South (separate schools, doors for public places, separate Bibles for swearing in, even the emergency blood supply, black women not allowed to try on or even touch clothes before purchase) De facto – practiced in the North (understood parameters, cultural, redlining in which banks and realtors would keep people of color out of certain neighborhoods) Populist Movement collapsed in 1896 with the re-establishing of segregation laws. 1919 Red Summer – labeled for the volume of blood shed, whites attacking blacks. -

Challenging the U.S. Nuclear Tests:The Golden Rule Sails Again

Challenging the U.S. Nuclear Tests:The Golden Rule Sails Again Ann Wright Veterans for Peace Honolulu, Hawaii 96821 USA Email: [email protected] Abstract In January 1958, Andrew Bigelow and three other anti-nuclear activists attempted to sail the 30 foot ketch, The Golden Rule, from California into the U.S. nuclear testing zone in the Marshall Islands to try to stop nuclear testing. While on a stopover in Honolulu, a U.S. federal court issued an injunction barring the voyage of the Golden Rule into the nuclear test sites. Despite the injunction, the four crew members attempted to sail twice and were arrested by U.S. federal law enforcement officials, tried, convicted and given sixty-day sentences and imprisoned. 55 years later, The Golden Rule, was found in a small shipyard in Eureka, California and her historical significance recognized. The boat had suffered the ravages of time and was in terrible shape. She is being carefully renovated by members of Veterans for Peace who intend to sail the boat on the West Coast as an educational vessel that personifies opposition to militarism and the use of nuclear weapons. Using documents from the Quaker House in Honolulu, the saga of The Golden Rule is a part of the rich history of maritime Hawaii. Keywords: Pacific Nuclear Testing, Protest Ships, Marshall Islands, AEC, Greenpeace Introduction In 2010, Larry Zerlangs, the owner of a boatyard in Eureka, Northern California, hauled out of a nearby bay a 30 foot double-masted Alpha 30 sailboat that had broken loose of her moorings and sunk during a big storm. -

BIRMINGHAM PUBLIC LIBRARY Department of Archives and Manuscripts

BIRMINGHAM PUBLIC LIBRARY Department of Archives and Manuscripts Connor, Theophilus Eugene 'Bull' Papers, 1951, 1957-1963 Background: Theophilus Eugene Connor was born in Dallas County, Alabama in 1897. Trained as a telegraph operator, Connor settled in Birmingham in the 1920s and worked as a radio sports announcer. Capitalizing on his popularity with radio listeners and his well-known nickname (,Bull'), Connor entered politics in 1934 and was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives. Connor was elected Public Safety Commissioner of Birmingham in 1937, a position that gave him administrative authority over the city's police and fire departments, public schools, public health and the public libraries. He held this position until 1954, and held the position again from 1958 to 1963 when he was forced from office by a change in the city form of government. During his long political career Connor ran two unsuccessful campaigns for governor of Alabama and was a leader of the 1948 Dixiecrat revolt. From 1964 to 1973 he served as President of the Alabama Public Service Commission, the state agency that regulates public utilities. Connor died in Birmingham in 1973. Eugene 'Bull' Connor is most famous for his staunch defense of racial segregation and for ordering the use of police dogs and fire hoses to disperse civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham during the spring of 1963. Scope and Content: These papers, which consist of letters, memoranda, clippings, photographs, and reports are the office files kept by Connor during his last five years as Commissioner of Public Safety. The papers from Connor's earlier terms were destroyed when he left office in 1954.