Evaluating Cross-Border Natural Resource Management Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report: Southern Africa Regional Environmental Program

SOUTHERN AFRICA REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAM FINAL REPORT DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FINAL REPORT SOUTHERN AFRICA REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAM Contract No. 674-C-00-10-00030-00 Cover illustration and all one-page illustrations: Credit: Fernando Hugo Fernandes DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................................ ii Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 1 Project Context ...................................................................................................... 4 Strategic Approach and Program Management .............................................. 10 Strategic Thrust of the Program ...............................................................................................10 Project Implementation and Key Partners .............................................................................12 Major Program Elements: SAREP Highlights and Achievements .................. 14 Summary of Key Technical Results and Achievements .......................................................14 Improving the Cooperative Management of the River -

See the Itinerary Here

A pioneering expedition to the Cuito River region in southeastern Angola. This expedition will be the first of its kind into Angola exploring the remote Cuito River system and will essentially open the way for tourism into one of Africa’s last wilderness frontiers. There is no better way to experience a true African Safari Expedition than in the comfort and privacy of your own exclusive mobile safari camp. An exploratory journey through the wilderness with the intimacy and flexibility of your own camp, guide, boats, helicopter and staff compliment. We will move our partner mobile rig (operated by Botswana based Beagle Expeditions) and staff, keeping our high standards of service the same. • 8 night Angolan Expedition • Fully inclusive • Minimum 4 / Maximum 4 persons • Private helicopter use of more than 30 hours • Possibility of collaring three elusive Angolan elephants • Led by specialist guide Simon Byron Day 1 Day 6 • Arrival at the Cuito Cuanavale airport • Fly on to the upper Cuito River base camp. • Morning Battle field tour of Cuito Cuanavale and Lomba batlle Field. • Helicopter flight to the Cuando River in the Bico area. • Afternoon boat cruise. • Exploration of the Luiana. (Luiana fly camp) Day 2 Day 7 • Full day helicopter exploration over the source lakes, with fly • Morning helicopter exploration of the Luiana and Cuando River system camp at Cuanavale Source Lake. and visit to Jamba, Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA base. Afternoon boat cruise Days 3 on the Cuito River • Morning helicopter exploration down the Cuanavale River Day 8 in search of elusive elephant. • Morning helicopter exploration of lower Cuito and vast wilderness area • Afternoon walk. -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

Overview of the Cubango Okavango

Transboundary Cooperation for Protecting the Cubango- Okavango River Basin and Improving the Integrity of the Okavango Delta World Heritage Property Overview of the Cubango-Okavango River Basin in Angola: Challenges and Perspectives Maun, 3-4 June 2019 Botswana National Development Plan (2018-2022) The National Development Plan 6 Axis provides framework for the development of infrastructure, 25 Policies environmental sustainability and land and territorial planning. 83 Programs Cubango-Okavango River Basin Key Challenges To develop better conditions for the economic development of the region. To foster sustainable development considering technical, socio- economic and environmental aspects. To combat poverty and increase the opportunities of equitable socioeconomic benefits. Key Considerations 1. Inventory of the water needs and uses. 2. Assessment of the water balance between needs and availability. 3. Water quality. 4. Risk management and valorization of the water resources. Some of the Main Needs Water Institutional Monitoring Capacity Network Decision- Participatory making Management Supporting Systems Adequate Funding Master Plans for Cubango Zambezi and Basins Cubango/ Approved in 6 main Up to 2030 Okavango 2016 programs Final Draft 9 main Zambezi Up to 2035 2018 programs Cubango/Okavango Basin Master Plan Main Programs Rehabilitation of degraded areas. Maintaining the natural connectivity between rivers and river corridors. Implementing water monitoring network. Managing the fishery activity and water use. Biodiversity conservation. Capacity building and governance. Zambezi Basin Master Plan Main Programs Water supply for communities and economic activities. Sewage and water pollution control. Economic and social valorisation of water resources. Protection of ecosystems. Risk management. Economic sustainability of the water resources. Institutional and legal framework. -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

Fy14 Q4 Quarterly Report with Fy14 Annual Supplement

FY14 Q4 QUARTERLY REPORT WITH FY14 ANNUAL SUPPLEMENT SOUTHERN AFRICA REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAM OCTOBER 2013 TO SEPTEMBER 2014 October 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 I. FY14 Q4 QUARTERLY SUMMARY: JULY – SEPTEMBER 2014 ......................... 5 A. Highlights of Key Activities ............................................................................................ 5 B. Summary of Progress against Planned Activities .......................................................... 7 C. Quarterly Summary by Program Elements .................................................................. 14 II. ANNUAL SUPPLEMENT TO THE QUARTERLY REPORT ............................... 25 A. Annual Summary by Program Element ....................................................................... 25 B. Additional Progress Toward Results and Other Contractual Requirements ................. 32 C. Transforming Lives Summary ..................................................................................... 34 ANNEX A. BENCHMARKS AND PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT ..................... 36 ANNEX B. ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLIANCE ....................................................... 42 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS CA Conservation -

S Angola on Their Way South

Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – Angola ■ ANGOLA W. R. J. DEAN Dickinson’s Kestrel Falco dickinsoni. (ILLUSTRATION: PETE LEONARD) GENERAL INTRODUCTION December to March. A short dry period during the rains, in January or February, occurs in the north-west. The People’s Republic of Angola has a land-surface area of The cold, upwelling Benguela current system influences the 1,246,700 km², and is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, climate along the south-western coast, and this region is arid in the Republic of Congo to the north-west, the Democratic Republic of south to semi-arid in the north (at about Benguela). Mean annual Congo (the former Zaïre) to the north, north-east, and east, Zambia temperatures in the region, and on the plateau above 1,600 m, are to the south-east, and Namibia to the south. It is divided into 18 below 19°C. Areas with mean annual temperatures exceeding 25°C (formerly 16) administrative provinces, including the Cabinda occur on the inner margin of the Coast Belt north of the Queve enclave (formerly known as Portuguese Congo) that is separated river and in the Congo Basin (Huntley 1974a). The hottest months from the remainder of the country by a narrow strip of the on the coast are March and April, during the period of heaviest Democratic Republic of Congo and the Congo river. rains, but the hottest months in the interior, September and October, The population density is low, c.8.5 people/km², with a total precede the heaviest rains (Huntley 1974a). -

Government of the Republic of Angola

New Partnership for Food and Agriculture Organization Africa’s Development (NEPAD) of the United Nations Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Investment Centre Division Development Programme (CAADP) GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA SUPPORT TO NEPAD–CAADP IMPLEMENTATION TCP/ANG/2908 (I) (NEPAD Ref. 05/15 E) Volume V of VI BANKABLE INVESTMENT PROJECT PROFILE Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector December 2005 ANGOLA: Support to NEPAD–CAADP Implementation Volume I: National Medium–Term Investment Programme (NMTIP) Bankable Investment Project Profiles (BIPPs) Volume II: Irrigation Rehabilitation and Sustainable Water Resources Management Volume III: Rehabilitation of Rural Marketing and Agro–Processing Infrastructures Volume IV: Agricultural Research and Extension Volume V: Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector Volume VI: Integrated Support Centres for Artisanal Fisheries NEPAD–CAADP BANKABLE INVESTMENT PROJECT PROFILE Country: Angola Sector of Activities: Forestry Proposed Project Name: Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector Project Area: Selected Regions of Angola Duration of Project: 5 years Estimated Cost: Foreign Exchange...............US$44.2 million Local Cost...........................US$30.6 million Total ...................................US$74.8 million Suggested Financing: Source US$ million % of total Government 8.8 12 Financing institution(s) 44.2 59 Private sector 21.8 29 Total 74.8 100 ANGOLA: NEPAD–CAADP Bankable Investment Project Profile “Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector” Table of Contents Abbreviations....................................................................................................................................... -

Portugal and South Africa

50 PORTUGAL AND SOUTH AFRICA: CLOSE ALLIES OR UNWILLING PARTNERS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA DURING THE COLD WAR? ____________________________________________________________________ Paulo Correia, Department of Historical Studies, with Prof Grietjie Verhoef, Department of Accountancy, University of Johannesburg Abstract The popular perception of the existence of a straightforward alliance between Portugal and South Africa as a result of the growing efficacy of African nationalist groups during the 1960s and early 1970s has never been seriously questioned. However, new research into recently declassified documents from the Portuguese military archives and an extensive overview of the Portuguese and South African diplomatic records from that period provide a different perception of what was certainly a complex interaction between the two countries. It should be noted that, although the two countries viewed their close interaction as mutually beneficial, the existing political differences effectively prevented the creation of an open strategic alliance that would have had a greater deterrence value instead of the secretive tactical approach that was used by both sides to resolve immediate security threats. In addition, South African support for Portugal’s long, difficult and costly counterinsurgency effort in three different operational theatres in Africa – Angola, Mozambique and Guinea Bissau – was not really decisive since such support was never provided on a significant scale. A brief analysis of South African-Portuguese relations before the 1960s From an early period, relations between the Union of South Africa and Portugal were strongly influenced by events that took place in the international arena. Moreover, Portuguese perceptions of its closest neighbours in Africa were based on an acute awareness of the United Kingdom’s dominant position on the African continent. -

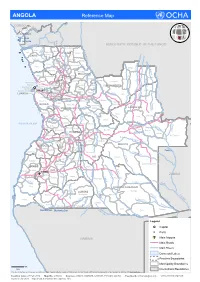

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

Trip Report: Aquatic Biodiversity Survey of the Lower Cuito and Cuando River Systems in Angola

Trip Report: Aquatic biodiversity survey of the lower Cuito and Cuando river systems in Angola. April 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. Table of Contents Introduction 3 Methods 5 Survey Timing 5 Survey Sites 5 Sampled Taxa 8 Results 9 Fish 9 Herpetofauna 15 Crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) 20 Botanical Report 25 Birds 35 Dragonflies and Damselflies 36 General observations 37 Observed threats to biodiversity 38 Way forward 39 i Southern African Regional Environmental Programme Executive Summary The Southern Africa Regional Environmental Program (SAREP) has a strategic goal to improve the conservation and sustainable use of biological resources of the Cubango- Okavango River Basin. This report fulfils one of the initial steps in helping to mitigate a critical threat to biodiversity within the system, i.e.; Poor Knowledge of the Status, Extent and Factors Regulating Biodiversity within the Basin (Indirect Threat) (SAREP, 2012), providing information on some of the aquatic faunal diversity of the Cubango-Okavango basin within Angola. This report provides a summary of the initial findings of the survey as well as general field conditions and observations. This survey is the second of its kind organised by the Southern African Regional Environmental Programme (SAREP) and the first survey took place in May 2012. The results of this initial survey were documented by Brooks (2012). The surveys are a collaborative venture between SAREP and the Angolan Ministry of Environment‟s (MINAMB) Institute of Biodiversity and the Angolan Ministry of Agricultures National Institute of Fish Research (INIP). -

Angola Livelihood Zone Report

ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………................……….…........……...3 Acronyms and Abbreviations……….………………………………………………………………......…………………....4 Introduction………….…………………………………………………………………………………………......………..5 Livelihood Zoning and Description Methodology……..……………………....………………………......…….…………..5 Livelihoods in Rural Angola….………........………………………………………………………….......……....…………..7 Recent Events Affecting Food Security and Livelihoods………………………...………………………..…….....………..9 Coastal Fishing Horticulture and Non-Farm Income Zone (Livelihood Zone 01)…………….………..…....…………...10 Transitional Banana and Pineapple Farming Zone (Livelihood Zone 02)……….……………………….….....…………..14 Southern Livestock Millet and Sorghum Zone (Livelihood Zone 03)………….………………………….....……..……..17 Sub Humid Livestock and Maize (Livelihood Zone 04)…………………………………...………………………..……..20 Mid-Eastern Cassava and Forest (Livelihood Zone 05)………………..……………………………………….……..…..23 Central Highlands Potato and Vegetable (Livelihood Zone 06)..……………………………………………….………..26 Central Hihghlands Maize and Beans (Livelihood Zone 07)..………..…………………………………………….……..29 Transitional Lowland Maize Cassava and Beans (Livelihood Zone 08)......……………………...………………………..32 Tropical Forest Cassava Banana and Coffee (Livelihood Zone 09)……......……………………………………………..35 Savannah Forest and Market Orientated Cassava (Livelihood Zone 10)…….....………………………………………..38 Savannah Forest and Subsistence Cassava