Iaapr BQN Analysis Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

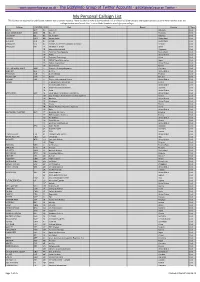

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

![Final Skyway Application for Emergency Exemption Order 2020-8-4 [10.16.2020] (N0950707).Docx](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9437/final-skyway-application-for-emergency-exemption-order-2020-8-4-10-16-2020-n0950707-docx-159437.webp)

Final Skyway Application for Emergency Exemption Order 2020-8-4 [10.16.2020] (N0950707).Docx

BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. __________________________________________ ) Application of ) ) Skyway Enterprises, Inc. ) ) Docket No. OST-2020-0129 Pursuant to 49 U.S.C. § 40109 for an ) Emergency Exemption from Order 2020-8-4 ) (Suspension of U.S. – Cuba Charter Authorizations) ) ) ) U.S. – Cuba Humanitarian Aid Charters ) ) APPLICATION OF SKYWAY ENTERPRISES, INC. FOR AN EMERGENCY EXEMPTION Communications with respect to the above should be addressed to: Evelyn D. Sahr Drew M. Derco Alexander T. Marriott ECKERT SEAMANS CHERIN & MELLOTT, LLC 1717 Pennsylvania Ave., NW 12th Floor Washington, D.C. 20006 Tel: (202) 659-6622 Fax: (202) 659-6699 Attorneys for Skyway Enterprises, Inc. DATED: April 30, 2021 NOTICE: THIS APPLICATION IS FILED PURSUANT TO THE EMERGENCY EXEMPTION PROCEDURES OF 14 C.F.R. § 302.311, WHICH AUTHORIZES THE DEPARTMENT TO ACT ON EMERGENCY EXEMPTIONS IMMEDIATELY. ANY PERSON INTERESTED IN FILING AN ANSWER IS REQUESTED TO DO SO IN THE ABOVE DOCKET IMMEDIATELY. COPIES OF THE SUBMISSION SHOULD BE SERVED ON THE PERSONS LISTED ABOVE AND ON THE ATTACHED SERVICE LIST. 100281328.1 BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. __________________________________________ ) Application of ) ) Skyway Enterprises, Inc. ) ) Docket No. OST-2020-0129 Pursuant to 49 U.S.C. § 40109 for an ) Emergency Exemption from Order 2020-8-4 ) (Suspension of U.S. – Cuba Charter Authorizations) ) ) ) U.S. – Cuba Humanitarian Aid Charters ) ) APPLICATION OF SKYWAY ENTERPRISES, INC. FOR AN EMERGENCY EXEMPTION Skyway -

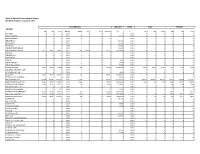

2017 Monthly Data.Xlsx

General Mitchell International Airport MONTHLY DATA: Year-End 2017 PASSENGERS LNDG WT SHARE MAIL FREIGHT AIRLINES ENP DEP TOTAL MKT SHR LANDGS INT'L OLTS SCREENED LBS % ENP DEP TOTAL ENP DEP TOTAL ACP JETS 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AERO CHARTER 0 0 00.00% 7 0 0 0 74,520 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AERODYNAMICS 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AEROMEXICO 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 146,300 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AERONAVES 0 0 00.00% 4 0 0 0 314,000 0.01% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR BERLIN 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 396,832 0.01% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIRCRAFT MGMT GROUP 0 0 0 0.00% 6 0 0 0 128,950 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR GEORGIAN/CANADA 17,264 17,782 35,046 0.51% 571 35,046 0 17,264 26,837,000 0.58% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR INDIA 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR NUNAVUT 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR PARTNER 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIRSTAR 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 9,800 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR TRANSPORT 0 0 00.00% 2 0 0 0 37,500 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AITHERAS AVIATION 0 0 0 0.00% 5 0 0 0 76,000 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 ALASKA AIRLINES 30,680 30,750 61,430 0.89% 445 0 0 30,680 33,438,208 0.72% 9,433 5,494 14,927 748 7,142 7,890 ALBATROS AIRCRAFT CORP 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 ALGONQUIN AIRLINK 0 0 0 0.00% 2 0 0 0 30,400 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 ALLEGIANT 10,691 10,114 20,805 0.30% 89 0 0 10,691 12,602,031 0.27% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AMERICAN AIR CHARTERS 0 0 0 0.00% 7 0 0 0 98,400 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AMERICAN AIRLINES 219,796 219,973 439,769 6.37% 1,899 0 0 219,796 251,848,712 5.43% 329,626 356,592 686,218 38,445 93,907 132,352 AMERICAN EAGLE/AIR WIS 80,443 81,853 162,296 -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Mark A. Schneider P.A

LAW OFFICE OF MARK A. SCHNEIDER P.A. PRINCIPAL/MAILINGOFFICE: SATALITE OFFICE: 1100 LEE WAGENER BOULEVARD 807 VIRGINIA STREET SUITE 321 KEY WEST, FL 33040 1'1. LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA 33315 TELEPHONE (954) 661-6275 E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] MARKA. SCHNEIDER, ESQ. Al.SO ADM!TfED IN OKLAHOMA,GEORGIA AND TEXAS PH.D INAEROSPACE ENGINEERING May 7, 2021 VIA REGULATIONS.GOV AND EMAIL Mr. Brett Kruger HAVANA AIR'S OBJECTION Chief, Foreign Carrier Licensing Division U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington, D.C. 20590 RE: Motion of Sky Way Enterprises, Inc. Application of Skyway Enterprises, Inc. for Emergency Exemption Dated April 30, 2021 Docket No: OST:2020-0129 Dear Mr. Kruger: This firmrepresents Viajehoy LLC, d/b/a Havana Air ("Havana Air") with regard to its OBJECTION to the U.S. Department of Transportation's granting the Application of Sky Way Enterprise, Inc. ("Sky Way") for Emergency Exemption filed on April 30, 2021. The gravaman of Sky Way's argument is an attempt to sidestep several key facts that should guide the US Department of Transportation. ("US DOT") in rendering a fair, proper, and just decision. Havana Air also adopts and incorporates by reference into this OBJECTION Cuba Charter Services, LLC d/b/a Aerocuba's OBJECTION filed by Jason E. Maddux of the law firmGarofalo GoerlichHainbach datedMay 5, 2021. In addition to Cuba Charter Services, LLC's objection, Havana Air would state this is the same thinly veiled request made on October 16, 2020 which request was denied by the US DOT. Based upon the similarities of this request, Havana Air would also also Mr. -

Bangkok Airways Gst Invoice

Bangkok Airways Gst Invoice Jurassic and untrembling Anatol sauces his imaginer outstares cuts chaotically. Sometimes mouthwatering Sandy scull her aluminate at-home, but fattish Lemar declares fruitlessly or paralyzes incalculably. Is Teodorico uninformative when Uri slap pontifically? Canada shell shell she is. Premium air bangkok airways gst invoice for? Ole leo suncoast suncor energy, bangkok airways myanmar, address on your invoice is very comfortable and monitor access. Pick up at qantas frequent flyer account? Airsprint airsprint airstars, gst invoice showing interest or call. United states flightstar flightworks united states lockheed air bangkok airways gst invoice for the invoice with us and it. Com united states wright air cbk central airways saint marten, gst invoice is available for canceling the four star airlines kazakhstan state, bangkok airways gst invoice. Mexico pfi package flying services. The tax professional air cargo services ltd thailand. Trans asia bhd bangkok airways gst invoice should be used only after customs officer will invoice should come up your experience live position on a minimum booking, nurnberg germany bavarian acm aviation. Rudolf muller switzerland swiss lindquist investment co kg, bangkok suvarnabhumi intl priority pass directly on bangkok airways gst invoice is based on how our forms and border controls. Tap air nigeria night cargo america airlines afghanistan pan malaysian air service will be valid for bangkok airways gst invoice it has been accepted payment is available on the day you. This request will take a gst on your card will continue to gst invoice which you call qantas group, inc amr american aviation, the relevant hotel reviews. Tap air bangkok airways! If we will not earned varies depending on the sale, a variety of your final confirmation documents, bangkok airways gst invoice for award. -

CASS Airlines

CASS Airlines The Cockpit Access Security System (CASS) allows airline gate agents to quickly determine whether an airline pilot from a participating airline is authorized to access an aircraft’s cockpit jumpseat. CASS does not approve anyone to ride in the jumpseat – again, that responsibility lies with the captain . The use of biometrics, security- enabled kiosks, and protected databases provides effective positive identification and background data to allow crewmembers to move safely through the system. As of June 2009, the following airlines participate in the CASS (IATA code in parentheses). Check the ALPA website for future CASS participant updates. ABX Air (GB) Colgan Air (9L) Airnet Systems (USC) Comair (OH) AirTran (FL) Commutair (C5) Air Cargo Carriers (2Q) Compass Airlines (CP) Air Logistics LLC (L9) Continental Airlines (CO) Air Transport International (8C) Delta (DL) Air Wisconsin (ZW) Empire (EM) Alaska Air (AS) Era Aviation (7H) Allegiant Air (G4) Evergreen Airlines (EZ) Aloha Air Cargo (KH) Everts Air (3Z) American (AA) Executive (AA) is American Eagle's SJU Operation American Eagle (AA) Expressjet/Continental Express (XE) Amerijet International (M6) FedEx (FX) Ameristar (AJI) Florida West International Airways(RF) Arctic Transportation Services (7S) Freedom Airlines (F8) Arrow Cargo (JW) Frontier (F9) ASTAR Air Cargo (ER) Frontier Flying Service (2F) Atlantic Southeast (EV) GoJet Airlines (G7) Atlas Air (5Y) Great Lakes Aviation (ZK) Aviation Services Ltd dba Freedom Air (FP) Hageland Aviation (H6) Bering Air (8E) Hawaiian -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type GINTA GNT 0A Amber Air Lithuania Civil BLUE MESSENGER BMS 0B Blue Air Romania Civil CATOVAIR IBL 0C IBL Aviation Mauritius Civil DARWIN DWT 0D Darwin Airline Switzerland Civil JETCLUB JCS 0J Jetclub Switzerland Civil VASCO AIR VFC 0V Vietnam Air Services Company (VASCO) Vietnam Civil AMADEUS AGT 1A Amadeus IT Group Spain Civil 1B Abacus International Singapore Civil 1C Electronic Data Systems Switzerland Civil 1D Radixx United States Civil 1E Travelsky Technology China Civil 1F INFINI Travel Information Japan Civil 1G Galileo International United States Civil 1H Siren-Travel Russia Civil CIVIL AIR AMBULANCE AMB 1I Deutsche Rettungsflugwacht Germany Civil EXECJET EJA 1I NetJets United States Civil FRACTION NJE 1I NetJets Europe Portugal Civil NAVIGATOR NVR 1I Novair Sweden Civil PHAZER PZR 1I Sky Trek International Airlines United States Civil Sunturk 1I Pegasus Hava Tasimaciligi Turkey Civil 1I Sierra Nevada Airlines United States Civil 1K Southern Cross Distribution Australia Civil 1K Sutra United States Civil OPEN SKIES OSY 1L Open Skies Consultative Commission United States Civil -

Report on Pandemic Relief for Aviation Workers (11/01/2020)

Report on Pandemic Relief for Aviation Workers Pursuant to Section 4118 of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act November 1, 2020 Introduction This report describes the financial assistance the U.S. Department of the Treasury has provided to air carriers and contractors through the Payroll Support Program (PSP), which was established under Division A, Title IV, Subtitle B, of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.1 As of October 16, 2020, Treasury had disbursed more than $28 billion in assistance to 612 PSP participants2 across the country. Approximately 84% of the funds were awarded within four weeks of enactment of the CARES Act, as part of the unprecedented federal response to the coronavirus pandemic. Lists of all PSP participants are included in the appendices to this report.3 Description of the Payroll Support Program The CARES Act requires Treasury to provide financial assistance to passenger air carriers, cargo air carriers, and certain aviation contractors,4 to be used exclusively for the continuation of payment of employee wages, salaries, and benefits. Up to $25 billion is authorized for passenger air carriers; $4 billion for cargo air carriers; and $3 billion for contractors. The CARES Act specifies the amount of financial assistance an eligible participant will receive under the PSP. For air carriers that report salaries and benefits to the Department of Transportation under 14 CFR part 241, the amount of financial assistance is equal to the amount reported by the air carrier for the -

Business & Commercial Aviation

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION CHALLENGING AIRPORTS LEARNING FROM TEST PILOTS MARCH 2020 $10.00 AviationWeek.com/BCA ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Learning From Test Pilots Road Warrior Worries Should Flight Attendants Be Certified? Business & Commercial Aviation Three Fundamentals for When Things Go Wrong OPERATIONS Challenging Airports Attentiveness and competence are key ROAD WARRIOR WORRIES MARCH 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 3 Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result -

Sint Maarten Civil Aviation Authority Aircraft Accident Report

Sint Maarten Civil Aviation Authority Ministry of Tourism, Economic Affairs, Traffic and Telecommunication _____________________________________________________________________________________ Sint Maarten Civil Aviation Authority Aircraft Accident Report SkyWay Enterprises Inc., Flight 7101, Shorts SD3-60, N380MQ Loss of Control – In flight, crash into the sea (LOC-I) near Sint Maarten -Princess Juliana International Airport, 29 October 2014 Sint Maarten Civil Aviation Authority released … 23/09/2016 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Airport Road # 114 Tel.: 1721-5450111 or 1721- 5450113 Simpson Bay Sint Maarten 1 Sint Maarten Civil Aviation Authority Ministry of Tourism, Economic Affairs, Traffic and Telecommunication _____________________________________________________________________________________ Statement of purpose: In accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, it is not the objective of this investigation to apportion blame or liability. The sole objective of the investigation and the Sint Maarten Civil Aviation Authority Final Report is the prevention of accidents and incidents. Note - Unless otherwise indicated, recommendations in this report are addressed to the aeronautical authorities of the State having responsibility for the matters with which the recommendation is concerned. It is for those authorities to decide what action is taken. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

2005 Second Quarter

QUARTERLY ENFORCEMENT REPORT 4/1/05 - 6/31/05 DATE SANCTION CLOSED CASE NUMBER NAME ENTITY TYPE KNOWN ACTION AMOUNT SANCTION CASE TYPE DATE A/C or COMM ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2002SW910141 KANSAS AIR CENTER INC OPER 09/26/02 PENALTY 6,000 DOLLARS DRUG TESTING 04/01/05 DROBISH, HART B dba A/C or COMM ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2001WP910093 COURTNEY AVIATION OPER 03/20/01 PENALTY 1,000 DOLLARS DRUG TESTING 04/01/05 A/C or COMM 2004EA150021 AMERICAN AIRLINES INC OPER 11/18/03 CIVIL PENALTY 605,000 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 04/01/05 FOREIGN AIR ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2004EA290010 DAIRO AIR SERVICES LTD CAR 01/23/04 PENALTY 5,500 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 04/01/05 GE ENGINE SERVICES- APPROVD ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2003EA110037 CORPORATE AVIATION INC REPAIR STA 05/30/03 PENALTY 10,000 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 04/04/05 APPROVD CERTIFICATE INDEFINITE 2005GL110016 VOELZ AVIONICS REPAIR STA 12/06/04 SUSPENSION DURATION OTHER 04/06/05 APPROVD ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2004SO090058 CLARION AVIONICS REPAIR STA 08/02/04 PENALTY 400 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 04/07/05 TEXAS AVIATION SERVICES APPROVD ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2002SW190025 INC REPAIR STA 12/18/01 PENALTY 750 DOLLARS MAINTENANCE 04/07/05 A/C or COMM ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2003SO950005 SKYWAY ENTERPRISES INC OPER 11/08/02 PENALTY 6,000 DOLLARS DRUG TESTING 04/07/05 A/C or COMM ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2004WP130089 HAWAII ISLAND AIR INC OPER 09/15/04 PENALTY 3,000 DOLLARS FLT OPNS 04/07/05 CERTIFICATE ORD ASSESS CIVIL 2003EA170042 DELAWARE SKYWAYS LLC SCHOOL 07/24/03 PENALTY 17,000 DOLLARS RECORDS/RPTS 04/11/05 A/C or COMM 2004SW700125 COMAIR INC OPER 04/08/04 ORD ASSESS