Personal Ornaments in Early Prehistory Marine and Freshwater Shell Exploitation in the Early Upper Paleolithic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends of Aquatic Alien Species Invasions in Ukraine

Aquatic Invasions (2007) Volume 2, Issue 3: 215-242 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/ai.2007.2.3.8 Open Access © 2007 The Author(s) Journal compilation © 2007 REABIC Research Article Trends of aquatic alien species invasions in Ukraine Boris Alexandrov1*, Alexandr Boltachev2, Taras Kharchenko3, Artiom Lyashenko3, Mikhail Son1, Piotr Tsarenko4 and Valeriy Zhukinsky3 1Odessa Branch, Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NASU); 37, Pushkinska St, 65125 Odessa, Ukraine 2Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas NASU; 2, Nakhimova avenue, 99011 Sevastopol, Ukraine 3Institute of Hydrobiology NASU; 12, Geroyiv Stalingrada avenue, 04210 Kiyv, Ukraine 4Institute of Botany NASU; 2, Tereschenkivska St, 01601 Kiyv, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] (BA), [email protected] (AB), [email protected] (TK, AL), [email protected] (PT) *Corresponding author Received: 13 November 2006 / Accepted: 2 August 2007 Abstract This review is a first attempt to summarize data on the records and distribution of 240 alien species in fresh water, brackish water and marine water areas of Ukraine, from unicellular algae up to fish. A checklist of alien species with their taxonomy, synonymy and with a complete bibliography of their first records is presented. Analysis of the main trends of alien species introduction, present ecological status, origin and pathways is considered. Key words: alien species, ballast water, Black Sea, distribution, invasion, Sea of Azov introduction of plants and animals to new areas Introduction increased over the ages. From the beginning of the 19th century, due to The range of organisms of different taxonomic rising technical progress, the influence of man groups varies with time, which can be attributed on nature has increased in geometrical to general processes of phylogenesis, to changes progression, gradually becoming comparable in in the contours of land and sea, forest and dimensions to climate impact. -

A Passion for Valpolicella Since 1843

A passion for Valpolicella since 1843 Beyond tradition: relaunch guidelines. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. 1.0 The value of tradition The winery’s history The Santi winery has been a leading producer in the Valpolicella area since 1843, the year it was established in Illasi, in the hills of the valley once called Longazeria. Carlo Santi was the first, followed by his successors Attilio Gino and Guido, to embark on a path that pursued excellence. Nowadays Cristian Ridolfi, Santi’s winemaker, embraces and continues this path, transforming the winery into a point of reference for the Valpolicella area in several Countries. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. 2 2.0 The land at the origins of our culture A knowledge of the terroir Santi’s wine maker constantly co-operate with the agronomic team to select the best rows in each valley of the Valpolicella area, considering the following features: soil, altitude, exposure and plant training system. This agronomic model allows Santi to create wines with a unique style, expression of the terroir variety among the several valleys that composes it. A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. 3 2.0 The land at the origins of our culture Santi’s selections in Valpolicella 1, FUMANE VALLEY Full bodied and dry wines 1 2 2, MARANO VALLEY Elegant wines of high aromatic intensity 3 4 5 3, NEGRAR VALLEY Tasty and long lived wines 4. VALPANTENA VALLEY Wines with spicy and mineral notes 5. ILLASI VALLEY Fragrant and very smooth wines with intense colour, NEW AREA OF VENTALE AREA OF PROEMIO AREA OF SOLANE VINEYARDS VINEYARDS VINEYARDS & AMARONE VINEYARDS A passion for Valpolicella since 1843. -

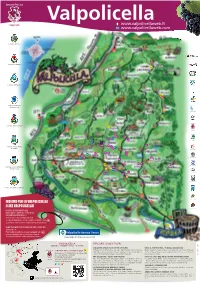

MAPPA-VALPO-2019.Pdf

Consorzio Pro Loco Valpolicella Valpolicella www.valpolicellaweb.it www.valpolicellaweb.com Comune di Dolcè Comune di Negrar 52 53 Comune di Fumane 49 39 Comune di Marano di Valpolicella 38 41 Consorzio Pro Loco Comune di Pescantina 51 Valpolicella 12 30 26 19 48 1 Pro Loco Molina 42 9 Comune di San Pietro 14 15 5 37 40 47 in Cariano 4 27 Pro Loco Volargne 7 11 13 16 35 44 17 23 46 18 10 Pro Loco Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo 29 36 54 20 21 8 31 Pro Loco Gargagnago Comune di Sant’Ambrogio 22 di Valpolicella 33 34 45 25 2 Pro Loco Breonio 3 43 24 32 6 Pro Loco San Giorgio 28 Comune di Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo Pro Loco Ospetaletto INSIEME PER LA VALPOLICELLA! 41 I LIKE VALPOLICELLA! Pro Loco Pescantina MOSTRA QUESTA MAPPA AGLI INSERZIONISTI ADERENTI E RICEVERAI UN BUONO SCONTO DEL 5% Trova l’elenco delle strutture aderenti 41 su valpolicellaweb.it o sul retro quelle con bollino rosso La promozione è valida secondo le condizioni applicate da ogni aderente. 50 SHOW THIS MAP TO PARTNERS AND GET A DISCOUNT TICKET OF 5% Find the list of partners on valpolicellaweb.com or those identi ed with a red dot on the back The promotion is valid under conditions applied by each member. www.valpolicellabenacobanca.it VALPOLICELLA PERCORSI / DAILY TOURS VERONA - VENETO - ITALY - EUROPE ANDAR PER CHIESE / TOUR OF THE CHURCHES VERSO IL PONTE DI VEJA / TOWARDS VEJA BRIDGE Consorzio Pro Loco CONSORZIO PRO LOCO VALPOLICELLA 54 Fumane (Grotta di Fumane – Santuario della Madonna de Le Salette – Negrar (Giardino Pojega, Chiesa di San Martino), Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo Villa della Torre), San Floriano (Pieve), Valgatara (Chiesa di San Marco), (Ponte di Veja – Museo Paleontologico e Preistorico), Fosse (Chiesa di Via Ingelheim, 7 - 37029 S. -

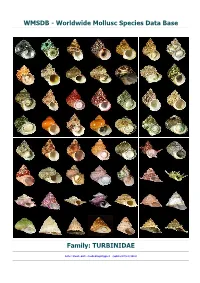

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

De Smit E. and Baba K., 2001. Data to The

MALAKOLÓGIAI TÁJÉKOZTATÓ MALACOLOGICAL NEWSLETTER 2001 19: 95–101 Data to the malacofauna of Katavothres (Kefalinia, Greece) E. De Smit–K. Bába Abstract: The authors evaluated the samples collected by Marninus De Smit in 1999 at the collection site of Katavothres, on the isle of Kefalinia, Greece. Key-words: Katavothers, Greece, Marin mollusc fauna Material and methods Sample collections were carried out in a southern bay of the isle of Kefalinia, on the coast of Katavothres (09.06.1999.) For the determination of the order of families we used Poppe, G. T.–Gotto, Y. (1991–1993) Vol. I-II. For the identification of species we gave preference to the following publications: Nordsieik, F. (1968, 1969, 1972) Poppe, G. T.–Gotto, Y. (1991, 1993), D’ Angeló–Gargiullo, S. (1978) and also Ghisotti, F.–Melone, G. (1971, 1972, 1975) Results The collections yielded species from Scaphopoda, Lamellibranchiata and Gastropoda class- es. Altogether 7697 individuals belonging to 188 species were collected. (Scaphopoda: 1 family 1 species, Lamellibranchiata: 30 families 90 species 3811 specimen, Gastropoda: 42 families 188 species 7697 specimen). From the Bivalvia the Musculus laevigatus is a cir- cumpolar, the Hiatellidae: Hiatella arctica is a boreal circumpolar species. From the Gastropoda the Trochidae: Clanculus striatus, Phasianellidae: Tricolia miniata are known as belonging to the Southern Mediterranean. Most probably they spread due shipping. From most of the species encountered 1-40 individuals were found. More than 100 indi- viduals were collected from the species below: Jujubinus striatus, Gibbula philberti, Truncatella subcylindrica, Alvania consociella, Bittium latreilli, Bittium reticulatum, Cerithium alucaster, Gibberula miliaria, Granulina clandestina. Summary From the alluvial deposits on an island near Greece 11 508 individuals from 279 species of 72 families from 3 orders were encountered. -

Die Arten Der Gattung Aporrhais Da Costa Im Ostatlantik Und

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Drosera Jahr/Year: 1977 Band/Volume: 1977 Autor(en)/Author(s): Cosel von Rudo Artikel/Article: Die Arten der Gattung Aporrhais da Costa im Ostatlantik und Beobachtungen zum Umdrehreflex der Peiikansfuß-Schnecke Aporrhais pespelecani (Mollusca: Prosobranchia) 37-46 DROSERA 77 (2): 37-46 Oldenburg 1977- I X Die Arten der Gattung Aporrhais da Costa im Ostatlantik und Beobachtungen zum Umdrehreflex der Peiikansfuß-Schnecke Aporrhais pespelecani (Mollusca: Prosobranchia) Rudo von Cosel *) Abstract: A short survey with identification key of the four species of the gastropod genus Aporrhais in the East Atlantic is given. — A second type of „turning-back-reflex“ of A. pespelecani (after having put the snail with aper ture upwards), in which the animal bends its extended body round the outer lip and not round the columella as usual, is described and figured for the first time, as well as the observation that the species is able to turn round its shell not only on sandy bottom, but also on hard substrate. Der Pelikansfuß Aporrhais pespelecani (LINNÉ 1758) ist eine der auffallendsten Schneckenarten an der deutschen Nordseeküste und gleichzeitig die Typusart der auf den Atlantik beschränkten Gattung Aporrhais in der Familie Aporrhaidae. Gattung Aporrhais DA COSTA 1778 1778 Aporrhais DA COSTA, Brit. Conch.: 136 1836 Chenopus PHILIPPI, Enum. Moll. Sic., t. I: 215 Gehäuse mit hochgetürmtem Gewinde und Schulterknoten oder Axialrippen. Äußerer Mündungsrand erweitert und zu fingerförmigen Fortsätzen ausgezogen. 5 rezente Arten, davon 2 boreal-lusitanisch-mediterrane und 2 westafrikanische Arten aus der Untergattung Aporrhais, sowie 1 arktisch-carolinische Art {A. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Belief, Ritual, and the Evolution of Religion

Belief, Ritual, and the Evolution of Religion Oxford Handbooks Online Belief, Ritual, and the Evolution of Religion Matt J. Rossano and Benjamin Vandewalle The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology and Religion Edited by James R. Liddle and Todd K. Shackelford Subject: Psychology, Personality and Social Psychology Online Publication Date: Oct 2016 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199397747.013.8 Abstract and Keywords This chapter outlines an evolutionary scenario for the emergence of religion. From cognitive science, four mental prerequisites of religious cognition are discussed: (1) hyperactive agency detection, (2) theory of mind, (3) imagination, and (4) altered states of consciousness. Evidence for these prerequisites in nonhuman primates suggests their presence in our early hominin ancestors. From comparative psychology, evidence of ritual behavior in nonhuman primates and other species is reviewed. Archeological evidence of ritual behavior is also discussed. Collectively, these data indicate that the first step toward religion was an elaboration of primate social rituals to include group synchronized activities such as dancing, chanting, and singing. Control of fire, pigment use, and increasing brain size would have intensified group synchronized rituals over time, which, in the context of increased intergroup interactions, eventually led to the first evidence of supernatural ritual at about 70,000 years before present. Keywords: agency detection, burial, cave art, costly signals, evolution, religion, ritual, synchronized movement, theory of mind Anyone interested in probing the evolutionary origins of religion faces a formidable challenge: Belief is central to religion, and belief does not fossilize in the archeological record. Looking at a half-million-year-old Acheulean hand axe may tell us something about the maker’s technical skills, diet, hunting practices, and lifestyle, but very little about his or her beliefs—let alone the supernatural beliefs inherent to most religions. -

Vocabulaires Et Toponymie Des Pays De Montagne

VOCABULAIRES et TOPONYMIE des pays de MONTAGNE Robert LUFT Club Alpin Français de Nice – Mercantour 2 Vocabulaires et toponymie des pays de montagne Avant-Propos Tels qu'ils se présentent à nos yeux, les paysages sont le résultat de l'action millénaire des forces de la nature sur le socle des terres émergées, conjuguée avec celle des interventions humaines. Les plaines et leurs abords collinaires sont caractérisés aujourd'hui par une agriculture mécanisée, par l'importance des réseaux de voies de communication, ainsi que par une urbanisation envahissante. Au cours de la seconde moitié du 20ème siècle, les paysages agricoles ouverts, traditionnellement formés de champs et de bocages microparcellaires, ont cédé la place à de vastes étendues dénudées, indispensables à la pratique des nouveaux modes de culture. Par ailleurs, beaucoup de villages et de bourgs dépérissent ou se transforment en cités-dortoirs de grandes agglomérations de plus en plus envahissantes. Pour décrire son paysage de plaine le citadin, désormais majoritaire, n'a plus recours aux termes nuancés de quelqu'un qui tire son existence des produits de la terre ; son mode d'expression est plus technique, mais aussi plus pauvre que celui du cultivateur d'antan. Dans les zones de la montagne, au contraire, l'aspect du paysage a peu évolué, malgré l'apparition de nouvelles techniques agricoles. Les formes variées du terrain imposent leur marque aux paysages dont les structures naturelles sont celles d'espaces clos, limités par des barrières rocheuses et des cours d'eau, infranchissables par endroits. Ces milieux âpres dont, il y a peu encore, il était difficile de s'échapper sans d'importants efforts physiques, limitent les échanges. -

Mollusc Fauna of Iskenderun Bay with a Checklist of the Region

www.trjfas.org ISSN 1303-2712 Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 12: 171-184 (2012) DOI: 10.4194/1303-2712-v12_1_20 SHORT PAPER Mollusc Fauna of Iskenderun Bay with a Checklist of the Region Banu Bitlis Bakır1, Bilal Öztürk1*, Alper Doğan1, Mesut Önen1 1 Ege University, Faculty of Fisheries, Department of Hydrobiology Bornova, Izmir. * Corresponding Author: Tel.: +90. 232 3115215; Fax: +90. 232 3883685 Received 27 June 2011 E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 13 December 2011 Abstract This study was performed to determine the molluscs distributed in Iskenderun Bay (Levantine Sea). For this purpose, the material collected from the area between the years 2005 and 2009, within the framework of different projects, was investigated. The investigation of the material taken from various biotopes ranging at depths between 0 and 100 m resulted in identification of 286 mollusc species and 27542 specimens belonging to them. Among the encountered species, Vitreolina cf. perminima (Jeffreys, 1883) is new record for the Turkish molluscan fauna and 18 species are being new records for the Turkish Levantine coast. A checklist of Iskenderun mollusc fauna is given based on the present study and the studies carried out beforehand, and a total of 424 moluscan species are known to be distributed in Iskenderun Bay. Keywords: Levantine Sea, Iskenderun Bay, Turkish coast, Mollusca, Checklist İskenderun Körfezi’nin Mollusca Faunası ve Bölgenin Tür Listesi Özet Bu çalışma İskenderun Körfezi (Levanten Denizi)’nde dağılım gösteren Mollusca türlerini tespit etmek için gerçekleştirilmiştir. Bu amaçla, 2005 ve 2009 yılları arasında sürdürülen değişik proje çalışmaları kapsamında bölgeden elde edilen materyal incelenmiştir. -

Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Molluscs

Cell and Tissue Research (2019) 377:475–503 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03085-9 REVIEW Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs Alexandre Lobo-da-Cunha1,2 Received: 21 February 2019 /Accepted: 26 July 2019 /Published online: 2 September 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The phylum Mollusca is one of the largest and more diversified among metazoan phyla, comprising many thousand species living in ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Mollusc-feeding biology is highly diverse, including omnivorous grazers, herbivores, carnivorous scavengers and predators, and even some parasitic species. Consequently, their digestive system presents many adaptive variations. The digestive tract starting in the mouth consists of the buccal cavity, oesophagus, stomach and intestine ending in the anus. Several types of glands are associated, namely, oral and salivary glands, oesophageal glands, digestive gland and, in some cases, anal glands. The digestive gland is the largest and more important for digestion and nutrient absorption. The digestive system of each of the eight extant molluscan classes is reviewed, highlighting the most recent data available on histological, ultrastructural and functional aspects of tissues and cells involved in nutrient absorption, intracellular and extracellular digestion, with emphasis on glandular tissues. Keywords Digestive tract . Digestive gland . Salivary glands . Mollusca . Ultrastructure Introduction and visceral mass. The visceral mass is dorsally covered by the mantle tissues that frequently extend outwards to create a The phylum Mollusca is considered the second largest among flap around the body forming a space in between known as metazoans, surpassed only by the arthropods in a number of pallial or mantle cavity. -

Genetic Perspectives on Marine Biological Invasions

Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2009. 2:X--X doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163745 Copyright © 2009 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved 1941-1405/09/0115-0000$20.00 <DOI> 10.1146/ANNUREV.MARINE.010908.163745</DOI> GELLER ■ DARLING ■ CARLTON GENETICS OF MARINE INVASIONS GENETIC PERSPECTIVES ON MARINE BIOLOGICAL INVASIONS Jonathan B. Geller Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Moss Landing, California 95039; email: [email protected] John A. Darling National Exposure Research Laboratory, US EPA, Cincinnati, Ohio 45208; email: [email protected] James T. Carlton Williams College-Mystic Seaport Maritime Studies Program, Mystic, Connecticut 06355; email: [email protected] ■ Abstract The full extent to which both historical and contemporary patterns of marine biogeography have been reshaped by species introduced by human activities remains underappreciated. As a result, the full scale of the impacts of invasive species on marine ecosystems remains equally underappreciated. Recent advances in the application of molecular genetic data in fields such as population genetics, phylogeography, and evolutionary biology have dramatically improved our ability to make inferences regarding invasion histories. Genetic methods have helped to resolve longstanding questions regarding the cryptogenic status of marine species, facilitated recognition of cryptic marine biodiversity, and provided means to determine the sources of introduced marine populations and to begin to recover the patterns of anthropogenic reshuffling of the ocean’s biota. These approaches