Naypyidaw's Drug Addiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Governor-General of India in Council Concerning the Administration of the State of Thibaw (1887)

xxxi .APPENDIX VII• (i) FORM OF SAN.AD GRANTED TO SAWBWAS. 1 WHE:REAS the of was formerly a subject to the ]fing of Burma, and the Governor-General of India in Council has now been pleased to reo·ognise you"· as of and, subject to the provisions of any law for the time being in force, to permit you to administer the territory of . in all matters, whether civil, criminal or revenue, and at an;y time to nominate for the approval. of the Chief Commissioner a fit person according to Shan usage to be your successor in the * * * * Paragraph 2.- The Chief Commissioner of Burma, with the approval of the Governor-General of India in Council, hereby prescribes the following conditions under which your nomination as of is made. Should you fail to comply with any of these conditions you will be liable to have your powers as of rescinded. Paragraph 3. - The conditions are as follows: - (1) You shall pay regularly the same amount of tribute as heretofore paid, namely, Rs. a year now fixed for five years, that is to say, from the to the and the said tribute shall be liable to rev.ision ·at the e)CI)iration of the said term, or at any time thereafter that the Chief Conunissioner of Burma may think fit. (2) The Government reserves to itself the proprietary rights in all forests, mines, and minerals. If you are permitted to work or to let on lease any forest or forests in your State, you shall pay such sums for rent or royalty as the Local Government may from time to time direct; and in the working of such forests you shall be guided by such rules and orders·as the Government of India may from time to time prescribe. -

Gold Mining in Shwegyin Township, Pegu Division (Earthrights International)

Accessible Alternatives Ethnic Communities’ Contribution to Social Development and Environmental Conservation in Burma Burma Environmental Working Group September 2009 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ......................................................................................... iii About BEWG ................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ...................................................................................... v Notes on Place Names and Currency .......................................................... vii Burma Map & Case Study Areas ................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 Arakan State Cut into the Ground: The Destruction of Mangroves and its Impacts on Local Coastal Communities (Network for Environmental and Economic Development - Burma) ................................................................. 2 Traditional Oil Drillers Threatened by China’s Oil Exploration (Arakan Oil Watch) ........................................................................................ 14 Kachin State Kachin Herbal Medicine Initiative: Creating Opportunities for Conservation and Income Generation (Pan Kachin Development Society) ........................ 33 The Role of Kachin People in the Hugawng Valley Tiger Reserve (Kachin Development Networking Group) ................................................... 44 Karen -

December 2009 UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) Promotes the Development and Maintenance of a Global Network of Illicit Crop Monitoring Systems

Central Committee for Lao National Commission for Drug Abuse control Drug Control and Supervision Opium Poppy Cultivation in South-East Asia Lao PDR, Myanmar December 2009 UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems. ICMP provides overall coordination as well as quality control, technical support and supervision to UNODC supported illicit crop surveys at the country level. The implementation of UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in South East Asia was made possible thanks to financial contributions from the Governments of Japan and the United States of America. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop-monitoring/index.html The boundaries, names and designations used in all maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document has not been formally edited. CONTENTS PART 1 REGIONAL OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................7 OPIUM POPPY CULTIVATION IN SOUTH EAST ASIA ...................................................................7 ERADICATION.......................................................................................................................................9 OPIUM YIELD AND PRODUCTION..................................................................................................11 -

National Transport Master Plan

Ministry of Transport The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Survey Program for the National Transport Development Plan in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Final Report September 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd. International Development Center of Japan EI ALMEC Corporation JR 14-192 Ministry of Transport The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Survey Program for the National Transport Development Plan in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Final Report September 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd. International Development Center of Japan ALMEC Corporation Exchange rate used in this Report USD 1.00 = JPY 99.2 USD 1.00 = MMK 970.9 MMK 1.00 = JPY 0.102 (As of October, 2013) Project Location Map The Survey Program for the National Transport Development Plan in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar A grand design for the transport sector at the dawn of new and modern era of transport development in Myanmar Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. Introduction 1.1 MYT-Plan Goals and Objective ..................................................................................... 1 - 1 1.2 Structure of the Master Plan ....................................................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Structure of the Report ................................................................................................ 1 - 3 Chapter 2. Socio-economic and Financial Frameworks 2.1 Demographic Framework ........................................................................................... -

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’S Mekong

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’s Mekong INSIDE: Blasting the Mekong Consequences of the Navigation Scheme Road Construction in Shan State: Turning Illegal Drug Profits into Legal Revenues Sold Down the River The tragedy of human trafficking on the Mekong No Place Left for the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves Intensive logging leaves few options for the Mabri people in Shan State ...and more The Lahu National Development January 2005 Organization (LNDO) The Mekong/ Lancang The Mekong River is Southeast Asia’s longest, stretching from its source in Tibet to the delta of Vietnam. Millions of people depend on it for agriculture and fishing, and accordingly it holds a special cultural significance. For 234 kilometers, the Mekong forms the border between Burma’s Shan State and Luang Nam Tha and Bokeo provinces of Laos. This stretch includes the infamous “Golden Triangle”, or where Burma, Laos and Thailand meet, which has been known for illicit drug production. Over 22,000 primarily indigenous peoples live in the mountainous region of this isolated stretch of the river in Burma. The main ethnic groups are Akha, Shan, Lahu, Sam Tao (Loi La), Chinese, and En. The Mekong River has a special significance for the Lahu people. Like the Chinese, we call it the Lancang, and according to legends, the first Lahu people came from the river’s source. Traditional songs and sayings are filled with references to the river. True love is described as stretching form the source of the Mekong to the sea. The beauty of a woman is likened to the glittering scales of a fish in the Mekong. -

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin and Northern Shan States (June 2017)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin and northern Shan States (June 2017) Htu San Ma Jawt Wawt Nam Din Lon Yein War Hkan 91 Ka Khin Ba Zu In Bu Bawt Ran Nam Nam Ton Khu 92 Nam Tar Lel Ah Lang Ga Ye Bang Ji Bon BHUTAN Hton Li Puta-O Htang Ga Yi Kyaw Di Machanbaw San Dam Zi Aun 90 Shin Mway Yang Hpar Tar Hpu Lum Hton Hpu Zar Lee Ri Dam Hpat Ma Di Ding Chet Mee Kaw INDIA Lo Po Te Mone Yat Chum Ding Lar Tee INDIA In Ga Ding Sar Tar Yaw CHINA Ma Jang Ga Shin Naw Ga Chi Nan Zee Dam Tan Gyar Shar Lar Ga Zee Kone KhaunglanhpuAh Ku Kun Sun Zan Yaw Tone Wi Nin BAN- GLA- Wa Det Hpi Zaw DESH Git Jar Ga In Zi Ran Ye Htan La Ja Khin Lum MYANMAR Hkawng Lang Tsum Pi Yang Ran Zain Nam Ching LAOS In Htut Ga Hta Hpone Nay Pyi Taw In Dang Ga Naw Yan Hpa Lar Dum Gan Ta Hton Kyin Kan Dar Chaung Dam Shin Bway Yang Hting Lu Yang Ta Seik Jahtung U Ma Ngar Yar Bay THAILAND Sha Chyum In Gaw Ma Dam Ga of Bum Wan Ta Hket Htaw Lang Bengal Yangon In Hkai In Ka Ron Tu Hting Nang La Kin Hka Hkauk Ta Ron Nawng Yar Jar Ran San Htu Nein Mar157 Gulf La Jar Bum Sumprabum Htam Dan Maw We 158 96 Khin Kyang Ga Wa Yoke of Sai Ran Shin Lon Ga Nawng Hkan Sar Chu Deik Hpar Martaban In Ta Ga Lu War Li Ga Sha Gu Ga La Yaung Wa Se Ma Kaw Su Yang Ma Dan Tu In Hpyin Ga Pa Din Ma Wun U Ma List of IDP Sites Za Nan Kha Hkaung Kawt Aum Ka Tu Ma Sa Hkan 100 Naw Lang Pa Kawt Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Tanai Bum Rong La Ja Bum 99 Kya Nar Yang Yit Chaw Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster 97 Wa Baw In Koi 98 La Myan Ka Htaung Chaw Han based on update of 1 June 2017 Zan Yu Yit Yaw Mai Khun (Mont Hkawm) Bum Rong Wa Ga Lun In Pawm Bum Hting Baing No. -

IDP 2011 Eng Cover Master

Map 7 : Southern and Central Shan State Hsipaw Mongmao INDIA Ta ng ya n CHINA Mongyai MYANMAR (BURMA) LAOS M Y A N M A R / B U R M A THAILAND Pangsang Kehsi Mong Hsu Matman Salween Mongyang S H A N S T A T E Mongket COAL MINE Mongla Mong Kung Pang Mong Ping Kunhing Kengtung Yatsauk Laikha Loilem Namzarng Monghpyak Mong Kok COAL MINE Taunggyi KENG TAWNG DAM COAL MINE Nam Pawn Mong Hsat Mongnai TASANG Tachilek Teng DAM Langkher Mongpan Mongton Mawkmai Hsihseng en Salwe Pekon T H A I L A N D Loikaw Kilometers Shadaw Demawso Wieng Hang Ban Mai 01020 K A Y A H S T A T E Nai Soi Tatmadaw Regional Command Refugee Camp Development Projects Associated with Human Rights Abuses Tatmadaw Military OPS Command International Boundary Logging Tatmadaw Battalion Headquarters State/Region Boundary Dam BGF/Militia HQ Rivers Mine Tatmadaw Outpost Roads Railroad Construction BGF/Militia Outpost Renewed Ceasefire Area (UWSA, NDAA) Road Construction Displaced Village, 2011 Resumed Armed Resistance (SSA-N) IDP Camp Protracted Armed Resistance (SSA-S, PNLO) THAILAND BURMA BORDER CONSORTIUM 43 Map 12 : Tenasserim / Tanintharyi Region INDIA T H A I L A N D CHINA MYANMAR Yeb yu (BURMA) LAOS Dawei Kanchanaburi Longlon THAILAND Thayetchaung Bangkok Ban Chaung Tham Hin T A N I N T H A R Y I R E G I O N Gulf Taninth of Palaw a Thailand ryi Mergui Andaman Sea Tanintharyi Mawtaung Bokpyin Kilometers 0 50 100 Kawthaung Development Projects Associated Tatmadaw Regional Command Refugee Camp with Human Rights Abuses Tatmadaw Military OPS Command International Boundary Gas -

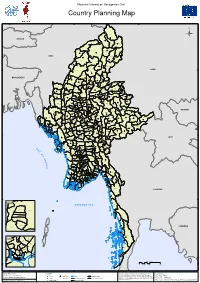

Mimu199v02 120423 Country Planning Map A1.Mxd

Myanmar Information Management Unit Country Planning Map 90°0'E 95°0'E 100°0'E Nawngmun (! Ü BHUTAN Puta-Ol (! Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun (! (! Tanai Tsawlaw Sumprabum Lahe INDIA Injangyang (! l Chipwi Hkamti Hpakan (! (! Lay Shi l.! (! (! Mogaung l Waingmaw (! (! Myitkyina CHINA Homalin 25°0'N l Mohnyin 25°0'N (! (! Momauk(! Banmauk (! (! BANGLADESH Indaw Shwegu Bhamol Tamu Paungbyin Katha (! (! (! Pinlebu (! Wuntho (! Muse Konkyan (! Mansi Tonzang (! Tigyaing Mawlaik Kawlin Namhkan Laukkaing Mabein (!Kutkai Kyunhla (! ! Thabeikkyin (!( Manton Kunlong (! Tedim Kalewa Hseni (! Kanbalu Hopang lKale Mongmit Namtu Taze Falam Namhsan l Mongmao Pangwaun Mogoke Lashio Mingin Ye-U ! Khin-U ( (! Thantlang (! .! Tabayin Kyaukme Shwebo (! Singu Namphan Kani Tangyan Hakha Budalin Hsipaw Pangsang Mongyai Wetlet Ayadaw Nawnghkio (! l Madaya l Yinmabin Monywa Gangaw (! Sagaing Patheingyi Pale Myinmu (! Chanayethazan.! Pyinoolwin Mongyang Salingyi Chaung-U l l Pyigyitagon Matman VIETNAM Madupi .! (! Amarapura Kyethi Ngazun Monghsu Tilin Myaung Tada-U Sintgaing Mongkaung l l ! Mongkhet Myaing ( Kyaukse (! (! Yesagyo Myingyan Lawksawk Mongla Pauk Mindat (! l Natogyi Maungdaw lSaw Ywangan (! Mongyawng(! Paletwa Myittha Laihka (! Mongping Pakokku Kunhing l Kengtung (! Taungtha (!l (! Wundwin Seikphyu Nyaung-U (! Buthidaung Mahlaing Pindaya Kanpetlet Hopong (! Kyauktaw l Loilen Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung l Taunggyi Nansangl (! Meiktila Thazi Chauk (! (!.! (! l (! (! Mrauk-U Salin Kalaw Mongnai Rathedaung Pyawbwe (! Tachileik Ponnagyun Monghsat Minbya Sidoktaya -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of OPIUM REDUCTION in BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES from the WA REGION Mr. Sai Lone a Thesis Submitted in Part

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION Mr. Sai Lone A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Program in International Development Studies Faculty of Political Science Chulalongkorn University Academic Year 2008 Copyright of Chulalongkorn University เศรษฐศาสตรการเมืองของการปราบฝนในประเทศพมา: มุมมองระดับทองถิ่นในเขตวา นายไซ โลน วิทยานิพนธน ี้เปนสวนหนึ่งของการศึกษาตามหลกสั ูตรปริญญาศิลปศาสตรมหาบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาการพัฒนาระหวางประเทศ คณะรัฐศาสตร จุฬาลงกรณมหาวิทยาลัย ปการศึกษา 2551 ลิขสิทธิ์ของจุฬาลงกรณมหาวิทยาลัย Thesis title: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION By: Mr. Sai Lone Field of Study: International Development Studies Thesis Principal advisor: Niti Pawakapan, Ph. D. Accepted by the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree ___________________________ Dean of the Faculty of Political Science (Professor Charas Suwanmala, Ph.D.) THESIS COMMITTEE ___________________________ Chairperson (Professor Supang Chantavanich, Ph.D.) ___________________________ Thesis Principal Advisor (Niti Pawakapan, Ph.D.) ___________________________ External Examiner (Decha Tangseefa, Ph.D.) นายไซ โลน: เศรษฐศาสตรการเมืองของการปราบฝนในประเทศพมา: มุมมองระดับ ทองถิ่นในเขตวา (THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION) อ. ทปรี่ ึกษา: ดร.นิติ ภวัครพันธุ. 133 หนา. งานวิจัยชิ้นนี้เนนศึกษาผลกระทบดานเศรษฐกิจสังคมของโครงการพัฒนาชนบทที่ดําเนินงานโดยองคกร -

Displacement and Poverty in South East Burma/Myanmar

It remains to be seen how quickly and effectively the new DISPLACEMENT government will be able to tackle poverty, but there has not yet been any relaxation of restrictions on humanitarian AND POVERTY access into conflict-affected areas. In this context, the vast majority of foreign aid continues to be channelled into areas IN SOUTH EAST not affected by armed conflict such as the Irrawaddy/ Ayeyarwady Delta, the Dry Zone and Rakhine State. While responding to demonstrated needs, such engagement is BURMA/MYANMAR building trust with authorities and supporting advocacy for increased humanitarian space throughout the country. Until this confidence building process translates into access, 2011 cross-border aid will continue to be vital to ensure that the needs of civilians who are affected by conflict in the South East and cannot be reached from Yangon are not further marginalised. overty alleviation has been recognised by the new A new government in Burma/Myanmar offers the possibility The opportunity for conflict transformation will similarly government as a strategic priority for human of national reconciliation and reform after decades of conflict. require greater coherence between humanitarian, political, Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC) development. While official figures estimate that a Every opportunity to resolve grievances, alleviate chronic development and human rights actors. Diplomatic www.tbbc.org quarter of the nation live in poverty, this survey poverty and restore justice must be seized, as there remain engagement with the Government in Naypidaw and the non Download the full report from Psuggests that almost two thirds of households in rural areas many obstacles to breaking the cycle of violence and abuse. -

The Burma Army's Offensive Against the Shan State Army

EBO The Burma Army’s Offensive Against the Shan State Army - North ANALYSIS PAPER No. 3 2011 THE BURMA ARMY’S OFFENSIVE AGAINST THE SHAN STATE ARMY - NORTH EBO Analysis Paper No. 3/2011 On 11 November 2010, a fire fight between troops of Burma Army Light Infantry Division (LID) 33 and Battalion 24 of the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N) 1st Brigade at Kunkieng-Wanlwe near the 1st Brigade’s main base, marked the beginning of the new military offensive against the ethnic armed groups in Shan and Kachin States. Tensions between the Burma Army and the ethnic groups, which had ceasefire agreements, started to mount after the Burma Army delivered an ultimatum in April 2009 for the groups to become Border Guard Forces. Prior to this, the Burma Army had always maintained that it did not have jurisdiction over political issues and that the groups could maintain their arms and negotiate with the new elected government for a political solution. Most of the larger ethnic groups refused to become BGFs, and in August 2009 the Burma Army attacked and seized control of Kokang (MNDAA), sending shock waves through the ethnic communities and the international community. Following the outcry, the Burma Army backed down and seemed content to let matters die down as it concentrated on holding the much publicized general elections on 7 November 2010. The attack against the SSA-N is seen was the first in a series of military offensives designed to fracture and ultimately destroy all armed ethnic opposition in the country’s ethnic borderlands.1 While the SSA-N lost its bases, this is unlikely to reduce its ability to conduct guerrilla operation against the Burma Army. -

SSA-S Government 11-Point Peace Agreement

SSA-S Government 11-point peace agreement 16 January 2012 RCSS/SSA and Union-Level Peace-making group signed an eleven-point peace agreement in Taunggyi, the capital of Shan State, on 16 Jan 2012. Unofficial Translation ........................................................................................................................................ 1. To allow RCSS/SSA headquarters in Homain sub-township and Mong Hta sub- township. 2. The government troops to negotiate and arrange in order that RCSS/SSA troops and their families be resettled in the locations mentioned in No. 1 3. RCSS/SSA will appoint village heads in the region; for township level administration the village heads will cooperate with government officials 4. Government soldiers in Homain sub-township and Mong Hta sub-township to give help to RCSS/SSA; Both sides will discuss and negotiate to arrange for the security of RCSS/SSA leaders 5. Government troops and RCSS/SSA to negotiate to designate areas where they can enter in border areas 6. Each side agreed to inform the other side in advance if one side wants to enter the other’s control area with weapons 7. To open liaison offices between the government and SSA-S in Taunggyi, Kholam, Kengtung, Mong Hsat and Tachileik and trading offices in Muse and Nanhkan 8. Government ministers to arrange for SSA-S members to run businesses and companies in accord with existing policies, by providing helps and supporting required technology 9. To cooperate with the union government for regional development 10. To cooperate with the government in making plan for battling drug trafficking 11. The government and RCSS/SSA agreed in principle to the points discussed on January 16, 2012.