Dedication: the Honorable Charles Clark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R. BROWN John R. Brown is a native Nebraskan. He was born in the town of Holdredge on December 10, 1909. Judge Brown remained in Ne- braska through his undergraduate education and received an A.B. degree in 1930 from the University of Nebraska. The Judge's legal education was attained at the University of Michigan, from which he received a J.D. degree in 1932. Both of Judge Brown's alma maters have conferred upon him Honorary LL.D. degrees. The University of Michigan did so in 1959, followed by the University of Nebraska in 1965. During World War II, the Judge served in the United States Air Force. Judge Brown was appointed to the United States Court of Ap- peals by President Eisenhower in July, 1955. Twelve years later, in July, 1967, he became Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Since 1967 the Judge has represented the Fifth Circuit at the Judicial Conference of the United States, as well as having been a member of its executive committee since 1972. The Judge is also a member of the Houston Bar Association, the Texas Bar Association, the American Bar Association, and the Maritime Law Association of the United States. Judge Brown is married to the former Mary Lou Murray and has one son, John R., Jr. The Judge currently lives in Houston. i, iiI IVA JUDGE RICHARD T. RIVES Richard T. Rives was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on Janu- ary 15, 1895. He attended Tulane University in the years 1911 and 1912. -

Constance Baker Motley, James Meredith, and the University of Mississippi

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY, JAMES MEREDITH, AND THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Denny Chin* & Kathy Hirata Chin** INTRODUCTION In 1961, James Meredith applied for admission to the University of Mississippi. Although he was eminently qualified, he was rejected. The University had never admitted a black student, and Meredith was black.1 Represented by Constance Baker Motley and the NAACP Legal De- fense and Educational Fund (LDF), Meredith brought suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, alleging that the university had rejected him because of his race.2 Although seven years had passed since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education,3 many in the South—politicians, the media, educators, attor- neys, and even judges—refused to accept the principle that segregation in public education was unconstitutional. The litigation was difficult and hard fought. Meredith later described the case as “the last battle of the * United States Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. ** Senior Counsel, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP. 1. See Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343, 345–46 (5th Cir. 1962) (setting forth facts); Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 697–99 (5th Cir. 1962) (same). The terms “black” and “Afri- can American” were not widely used at the time the Meredith case was litigated. Although the phrase “African American” was used as early as 1782, see Jennifer Schuessler, The Term “African-American” Appears Earlier than Thought: Reporter’s Notebook, N.Y. Times: Times Insider (Apr. 21, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/04/21/ the-term-african-american-appears-earlier-than-thought-reporters-notebook/ (on file with the Columbia Law Review); Jennifer Schuessler, Use of ‘African-American’ Dates To Nation’s Earliest Days, N.Y. -

To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look for Assistance:” Confederate Welfare in Mississippi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 "To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi Lisa Carol Foster University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Foster, Lisa Carol, ""To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi" (2017). Master's Theses. 310. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/310 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster August 2017 Approved by: _________________________________________ Dr. Susannah Ural, Committee Chair Professor, History _________________________________________ Dr. Chester Morgan, Committee -

• United States Court Directory

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. .f'"'" '''\ '. • UNITED STATES COURT DIRECTORY JULY 1,1979 • • UNITED STATES COURT DIRECTORY July 1, 1979 Published by: The Administrative Office of the United States Courts Contents: Division of Personnel Office of the Chief (633-6115) • Publication & Distribution: Administrative Services Division Management Services Branch Chief, Publications !1anagement Sectiom (633-6178) ". "!01 t' ",; "" t~ ~. ':"; t."l. t..:'r", / ERRATA SHEET • UNITED STA'IES COURT DIHECIDRY July 1, 1979 Page Change 2 D.C. Circuit -- Judge David L. Baze10n has taken senior status. 4 Second Circuit -- Judge William H. Mulligan, ~om 684, One Federal Plaza, New York, New York 10007. Add Judge Jon O. Newman, U. S. Courthouse, 450 Main Street, Hartford, CDnnecticut 06103 (FTS-244-3260). Add Judge Ama1ya Lyle Kearse, 1005 U. S. Courthouse, Foley Square, New York, New York 10007 (FTS-662-0903) (212-791-0903). 10 Fifth Circuit -- Judge Irving L. Goldberg (FTS-7~9-0758) (214-767-0758). 16 Eighth Circuit -- Judge M. C. Matthes, Box 140BB, Route 1, Highway F, Wright City, Missouri 63390. • 33 Arizona -- Add Judge Valdemar A. Cordova, 7418 Federal Building, phoenix, Arizona 85025 (FTS-261-4955) (602-261-4955). 34 Arkansas, Eastern -- Add Judge William Hay Overton, Post Office Box 1540, Little Rock 72203 (FTS-740-5682) (501-378-5682). 44 Connecticut -- Delete Judge Jon O. Newman. 46 District of Co1unbia -- Add Judge Joyce Hens Green, ?''Washington, D.C. 20001 CFTS-426-7581) (202-426-7581). 64 Iowa, Southern -- Add Judge Harold D. Vietor, 221 United States Court- house, Des MOines 50309 (FTS-862-4420) (515-284-4420). -

October Term, 1953

: : I JU«^k> £j£ OCTOBER TERM, 1953 STATISTICS Miscella- Original Appellate Total neous Number of cases on dockets 11 815 637 1, 463 Cases disposed of__ 0 694 609 1,303 Remaining on dockets __ 11 121 28 160 Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket By written opinions 84 By per curiam opinions 86 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merit cases) 2 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 522 Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket By written opinion 0 By per curiam opinion 0 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 507 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 92 By transfer to Appellate Docket 10 Number of written opinions 65 Number of printed per curiam opinions 11 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 88 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 31 Number of admissions to bar (133 admitted April 26) 1, 557 REFERENCE INDEX Page Court convened October 5. (President Eisenhower attended.) Vinson, C. J., death of (Sept. 8, 1953) announced- 1 Warren, C. J., commission (recess appointment) read and oath taken (Oct. permanent 5, 1953) ; commission recorded and oath taken March 20, 1954, filed 1, 181 Statement by Chief Justice as to his nonparticipation in mat- ters considered at first conference 6 Reed, J., temporarily assigned to Second Circuit 204 Herbert Brownell, Jr., Attorney General, presented 2 269533—54 71 : n Pag* Simon E. Sobeloff, Solicitor General, presented 150 Allotment of Justices 28 Attorney Change of name 147 Withdrawal of membership (Roscoe B. Stephenson) 235 Counsel appointed (121) 4 Special Master—pleadings referred to. -

Advise & Consent

The Los Angeles County Bar Association Appellate Courts Section Presents Advise & Consent: A Primer to the Federal Judicial Appointment Process Wednesday, October 28, 2020 Program - 12:00 - 1:30 PM Zoom Webinar CLE Credit: 1.5 Hours Credit (including Appellate Courts Specialization) Provider #36 The Los Angeles County Bar Association is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. The Los Angles County Bar Association certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California. PANELIST BIOS Judge Kenneth Lee (Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals) Kenneth Kiyul Lee is a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The U.S. Senate confirmed him on May 15, 2019, making him the nation’s first Article III judge born in the Republic of Korea. Prior to his appointment, Judge Lee was a partner at the law firm of Jenner & Block in Los Angeles, where he handled a wide variety of complex litigation matters and had a robust pro bono practice. Judge Lee previously served as an Associate Counsel to President George W. Bush and as Special Counsel to Senator Arlen Specter, then-chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee. He started his legal career as an associate at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz in New York. Judge Lee is a 2000 magna cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School and a 1997 summa cum laude graduate of Cornell University. He clerked for Judge Emilio M. Garza of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit from 2000 to 2001. Judge Leslie Southwick (Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals) Leslie Southwick was appointed to the U.S. -

Observations of Twenty-Five Years As a United States Circuit Judge Donald P

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 18 | Issue 3 Article 13 1992 Observations of Twenty-five Years as a United States Circuit Judge Donald P. Lay Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Lay, Donald P. (1992) "Observations of Twenty-five Years as a United States Circuit Judge," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 18: Iss. 3, Article 13. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol18/iss3/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Lay: Observations of Twenty-five Years as a United States Circuit Judg OBSERVATIONS OF TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AS A UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE DONALD P. LAYt INTRODUCTION Following my announcement that I was stepping down as Chief Judge and taking senior status after having served as an active judge on the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals for twenty- five years, I received many letters from lawyers, judges, and lay people from all parts of the country. One of my friends wrote that she felt it was the end of an era in the sense that, as of January 7, 1992, no active judge would be on the Eighth Cir- cuit Court of Appeals who had presided when I was appointed by President Johnson in 1966. My announcement has caused me to reflect on the many changes that have taken place on the court of appeals over the past quarter century. -

1955 Journal

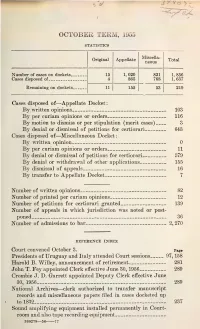

OCTOBER TERM, 1955 STATISTICS Miscella- Original Appellate Total neous Number of Gases on dockets 15 1, 020 821 1, 856 Cases disposed of 4 865 768 1, 637 Remaining on dockets. 11 155 53 219 Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket: By written opinions 103 By per curiam opinions or orders 116 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merit cases) 3 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 64& Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket : By written opinion 0 By per curiam opinions or orders 11 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 579 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 155 By dismissal of appeals 16 By transfer to Appellate Docket 7 Number of written opinions 82 Number of printed per curiam opinions 12 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 139 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 36 Number of admissions to bar 2, 270 REFERENCE INDEX Court convened October 3. Page Presidents of Uruguay and Italy attended Court sessions 97, 158 Harold B. Willey, announcement of retirement 281 John T. Fey appointed Clerk effective June 30, 1956 289 Crombie J. D. Garrett appointed Deputy Clerk effective June 30, 1956 289 National Archives—clerk authorized to transfer manuscript records and miscellaneous papers filed in cases docketed up to 1832 237 Sound amplifying equipment installed permanently in Court- room and also tape recording equipment 360278—56 77 Attorney : Page Motion for reinstatement of Norman J. Griffin granted and order of disbarment vacated (300 Misc.) 42 Disbarment of Orille C. Gaudette (336 Misc.) 103, 154 Change of name 88 Counsel appointed (489, 460, 714) 81, 119, 163 Special Master, compensation awarded (10 Orig.) 282 Rules of Criminal Procedure amended and reported to Con- gress 202 Opinion amended (23) 258 Orders and judgments amended (406 O. -

Judicial Branch

JUDICIAL BRANCH SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES One First Street, NE., Washington, DC 20543 phone (202) 479–3000 JOHN G. ROBERTS, JR., Chief Justice of the United States, was born in Buffalo, NY, January 27, 1955. He married Jane Marie Sullivan in 1996 and they have two children, Josephine and Jack. He received an A.B. from Harvard College in 1976 and a J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1979. He served as a law clerk for Judge Henry J. Friendly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1979–80 and as a law clerk for then Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist of the Supreme Court of the United States during the 1980 term. He was Special Assistant to the Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1981–82, Associate Counsel to President Ronald Reagan, White House Coun- sel’s Office from 1982–86, and Principal Deputy Solicitor General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1989–93. From 1986–89 and 1993–2003, he practiced law in Washington, DC. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 2003. President George W. Bush nominated him as Chief Justice of the United States, and he took his seat September 29, 2005. CLARENCE THOMAS, Associate Justice, was born in the Pin Point community near Savannah, Georgia on June 23, 1948. He attended Conception Seminary from 1967–68 and received an A.B., cum laude, from Holy Cross College in 1971 and a J.D. from Yale Law School in 1974. -

Accessions: 1998-1999

The Primary Source Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 6 1999 Accessions: 1998-1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Accessions: 1998-1999," The Primary Source: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. DOI: 10.18785/ps.2101.06 Available at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource/vol21/iss1/6 This Column is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rP imary Source by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~---------------------------- Accessions: 1998-1999 Mississippi Department of Archives and History Manuscript Collection BARKSDALE FAMILY PAPERS, ACCRETION. ca. 1960-1998.0.33 c.f. This accretion to the papers of the Barksdale family of Jackson, Mississippi, consists primarily of correspondence between Emily Woodson Barksdale Humphrey and her sister, Therese Hawkins Barksdale of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Also included are an occasional photograph and program, social papers, and materials relating to family history. Presented by Therese Hawkins Barksdale Vinsonhaler, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. CLARK (CHARLES) PAPERS, ACCRETION. ca. 1968-1973. 7.50 c.f. This accretion to the papers of Charles Clark of Jackson, Mississippi, consists of case files, correspondence, memoranda, and publications documenting a portion of his career as chief justice of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The case files in this accretion primarily concern school districts in southern states; among the issues addressed is desegregation. Presented by Charles Clark, Jackson, Mississippi. -

Meredith V. Fair, 202 F.Supp

Meredith v. Fair, 202 F.Supp. 224 (1962) motion for preliminary injunction was denied and the Court set the case for final hearing on January 15, 1962. 202 F.Supp. 224 United States District Court S.D. Mississippi, After fully hearing all the evidence and considering the Jackson Division. record on the motion for a preliminary injunction the Court held that the Plaintiff was not denied admission James Howard MEREDITH because of his race. The Plaintiff filed his notice of appeal v. from that judgment on December 14, 1961 to the Court of Charles Dickson FAIR et al. Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which appeal was heard on January 9, 1962 and the opinion rendered by the Court of Civ. A. No. 3130. Appeals on January 12, 1962, 298 F.2d 696, affirming the | judgment of the District Court, and the Court of Appeals Feb. 3, 1962. denied the motion of the Plaintiff to order the District Court to enter a preliminary injunction in time to secure the Plaintiff’s admission to the February 6 term of the Action brought by member of the Negro race asserting University. that he had been denied admission to the University of Mississippi solely because of his race. The District Court, The statement of the pleadings and the background of the Mize, Chief Judge. held that evidence established that facts leading up to the filing of the suit are contained in plaintiff was not denied admission to University of the *226 opinion of the District Court which was filed on Mississippi as resident, under-graduate, transfer student December 12, 1961 and which is reported in 199 F.Supp. -

The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-08 Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865 Ruminski, Jarret Ruminski, J. (2013). Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27836 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/398 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865 by Jarret Ruminski A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2012 © Jarret Ruminski 2012 Abstract This study uses Mississippi from 1860 to 1865 as a case-study of Confederate nationalism. It employs interdisciplinary literature on the concept of loyalty to explore how multiple allegiances influenced people during the Civil War. Historians have generally viewed Confederate nationalism as weak or strong, with white southerners either united or divided in their desire for Confederate independence. This study breaks this impasse by viewing Mississippians through the lens of different, co-existing loyalties that in specific circumstances indicated neither popular support for nor rejection of the Confederacy.