NYU Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

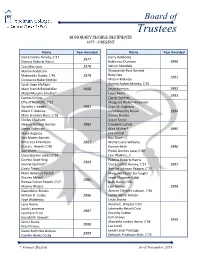

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

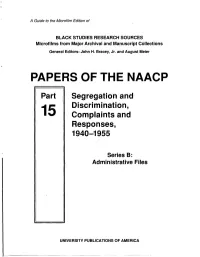

PAPERS of the NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloglng-ln-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial--[etc.]--pt. 15. Segregation and discrimination, complaints and responses, 1940-1955. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People-Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century-Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations-Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- . -

Rker High Inspired Ca Lotta Harris to Teach

February 26 - March 4, 1998 page 17 A Tribute To A.H. Parker High School .H. Parker High School has maintained a stately position on 8th Avenue. This artist rendering shows a building that has since been removed, but tillihes in the hearts of thousand nh .. gained a foundation Cor success at Birmingham's oldest high school for African American student~. rker High Inspired Ca lotta Harris To Teach By Shcrrel Wheeler Stewart Harris has taught at Parker al vided the paint and some tools, and ted 38 years to the education of stu and went to North Carolina A&T you have push and pull, but when most every day for the past 43 years. the shop students and others rolled dents of that institution, was first in UnIversity After teachlllg in North Ihey develop a sense of prid.:, you Like thousands of alumni who have up theIr sleeves to turn the cOllages efforts to prepare BIrmingham city Carolina ahout 10 years. he returned can see the difference." attended Birmingham's most presti into a school. residents wilh a challenging high 10 Alabama and taught in the Bir Dansoy silid school pride has gious high school, Harris said, "once In 1933 news articles, Dr. A.H., school curricululn mingham school system 2H years been on or Ihe reasons for the change you havc been part of the Parker ex Parker said: "I asked the people liv The school has maintained ils befon: rctmng in Ihe ~chool's reputation in recent pcricnce, it will always be a part of ing in the cottages to vacote as soon reputallon over Ihe years. -

Brown V. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society

Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society Manuscript Collection No. 251 Audio/Visual Collection No. 13 Finding aid prepared by Letha E. Johnson This collection consists of three sets of interviews. Hallmark Cards Inc. and the Shawnee County Historical Society funded the first set of interviews. The second set of interviews was funded through grants obtained by the Kansas State Historical Society and the Brown Foundation for Educational Excellence, Equity, and Research. The final set of interviews was funded in part by the National Park Service and the Kansas Humanities Council. KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Topeka, Kansas 2000 Contact Reference staff Information Library & archives division Center for Historical Research KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 6425 SW 6th Av. Topeka, Kansas 66615-1099 (785) 272-8681, ext. 117 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.kshs.org ©2001 Kansas State Historical Society Brown Vs. Topeka Board of Education at the Kansas State Historical Society Last update: 19 January 2017 CONTENTS OF THIS FINDING AID 1 DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION ...................................................................... Page 1 1.1 Repository ................................................................................................. Page 1 1.2 Title ............................................................................................................ Page 1 1.3 Dates ........................................................................................................ -

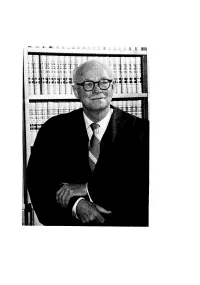

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R. BROWN John R. Brown is a native Nebraskan. He was born in the town of Holdredge on December 10, 1909. Judge Brown remained in Ne- braska through his undergraduate education and received an A.B. degree in 1930 from the University of Nebraska. The Judge's legal education was attained at the University of Michigan, from which he received a J.D. degree in 1932. Both of Judge Brown's alma maters have conferred upon him Honorary LL.D. degrees. The University of Michigan did so in 1959, followed by the University of Nebraska in 1965. During World War II, the Judge served in the United States Air Force. Judge Brown was appointed to the United States Court of Ap- peals by President Eisenhower in July, 1955. Twelve years later, in July, 1967, he became Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Since 1967 the Judge has represented the Fifth Circuit at the Judicial Conference of the United States, as well as having been a member of its executive committee since 1972. The Judge is also a member of the Houston Bar Association, the Texas Bar Association, the American Bar Association, and the Maritime Law Association of the United States. Judge Brown is married to the former Mary Lou Murray and has one son, John R., Jr. The Judge currently lives in Houston. i, iiI IVA JUDGE RICHARD T. RIVES Richard T. Rives was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on Janu- ary 15, 1895. He attended Tulane University in the years 1911 and 1912. -

On Being a Black Lawyer 2013 Power

2013 SALUTES THE MOSTBLACK INFLUENTIAL LAWYERS IN THE NATION 100 AND DIVERSITY ADVOCATES CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR POWER 100 HONOREES WE SALUTE OUR AFRICAN AMERICAN PARTNERS We salute Chief Diversity Officer Theresa Cropper and Firmwide Executive Committee Chair Laura Neebling for being recognized as Power 100 honorees. As a Pipeline Builder, Ms. Cropper has invested in the diversity pipeline throughout her career and prepared students at every level to pursue their dreams. As an Advocate, Ms. Neebling has championed diversity and inclusion at the firm and lent her leadership to initiatives that advance the cause. Perkins Coie is proud of their contributions and extends warmest congratulations to them both. ALLEN CANNON III DENNIS HOPKINS SEAN KNOWLES RICHARD ROSS Government Contracts, Washington, D.C. Commercial Litigation, New York Commercial Litigation, Seattle Business, New York PHILIP THOMPSON LINDA WALTON JAMES WILLIAMS BOBBIE WILSON Labor, Bellevue Labor, Seattle Commercial Litigation, Seattle Commercial Litigation, San Francisco THERESA CROPPER LAURA NEEBLING Chief Diversity Officer Chair, Firmwide Executive Committee At Perkins Coie, we believe that diversity is a key ingredient to success. We benefit from diverse perspectives that allow us to deliver excellent counsel to our clients. At Perkins Coie, Diversity is a Key Ingredient. We support On Being a Black Lawyer in recognizing the contributions of the Power 100 (2013) honorees. ANCHORAGE · BEIJING · BELLEVUE · BOISE · CHICAGO · DALLAS · DENVER ANCHORAGE · BEIJING · BELLEVUE · BOISE · CHICAGO · DALLAS · DENVER LOS ANGELES · MADISON · NEW YORK · PALO ALTO · PHOENIX · PORTLAND LOS ANGELES · MADISON · NEW YORK · PALO ALTO · PHOENIX · PORTLAND SAN DIEGO · SAN FRANCISCO · SEATTLE · SHANGHAI · TAIPEI · WASHINGTON, D.C. SAN DIEGO · SAN FRANCISCO · SEATTLE · SHANGHAI · TAIPEI · WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Constance Baker Motley, James Meredith, and the University of Mississippi

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY, JAMES MEREDITH, AND THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Denny Chin* & Kathy Hirata Chin** INTRODUCTION In 1961, James Meredith applied for admission to the University of Mississippi. Although he was eminently qualified, he was rejected. The University had never admitted a black student, and Meredith was black.1 Represented by Constance Baker Motley and the NAACP Legal De- fense and Educational Fund (LDF), Meredith brought suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, alleging that the university had rejected him because of his race.2 Although seven years had passed since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education,3 many in the South—politicians, the media, educators, attor- neys, and even judges—refused to accept the principle that segregation in public education was unconstitutional. The litigation was difficult and hard fought. Meredith later described the case as “the last battle of the * United States Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. ** Senior Counsel, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP. 1. See Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343, 345–46 (5th Cir. 1962) (setting forth facts); Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 697–99 (5th Cir. 1962) (same). The terms “black” and “Afri- can American” were not widely used at the time the Meredith case was litigated. Although the phrase “African American” was used as early as 1782, see Jennifer Schuessler, The Term “African-American” Appears Earlier than Thought: Reporter’s Notebook, N.Y. Times: Times Insider (Apr. 21, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/04/21/ the-term-african-american-appears-earlier-than-thought-reporters-notebook/ (on file with the Columbia Law Review); Jennifer Schuessler, Use of ‘African-American’ Dates To Nation’s Earliest Days, N.Y. -

Constance Baker Motley

THE HONORABLE CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY The Honorable Constance Baker Motley is an extraordinary person, and one of the noteworthy and surprising facts about her is how little has been written about her life and work. If, after this presentation, you are interested in learning more about her, you might read her autobiography, Equal Justice Under Law,1 and you might watch a videotape of a 1988 interview of her conducted by Alfred Aman, Professor and former dean at the Indiana University School of Law at Bloomington.2 Our library can secure the videotape for you through interlibrary loan. The bibliography lists other materials relevant to her life and work. Here are several striking facts about Constance Baker Motley, any one of which would make her worthy of serious study. She was the fifth woman, and the first Black woman, appointed to the federal bench.3 She served for almost twenty years, from 1946 to 1964, as staff attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and was part of the "inner circle" responsible for Brown v. Board of Education, a case that many consider to be the most important of the twentieth century.4 She represented James Meredith in his successful attempt to integrate the University of Mississippi, integration that was accomplished only with the 1Constance Baker Motley, Equal Justice Under the Law (1998). 2An interview with Judge Constance Baker Motley conducted by Alfred C. Aman (1988). 3Linn Washington, Black Judges on Justice (1995), p. 760. 4Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality, (2004), p. -

Entrepreneurial Spirit

502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/10/08 11:35 AM Page 1 Amicus UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO LAW SCHOOL VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 2, FALL 2008 The Entrepreneurial Spirit Inside: • $5 M Gift for Schaden Chair in Experiential Learning • Honor Roll of Donors 502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/10/08 9:21 AM Page 2 Amicus AMICUS is produced by the University of Colorado Law School in conjunction with University Communications. Electronic copies of AMICUS are available at www.colorado.edu/law/alumdev. S Inquiries regarding content contained herein may be addressed to: la Elisa Dalton La Director of Communications and Alumni Relations S Colorado Law School 401 UCB Ex Boulder, CO 80309 Pa 303-492-3124 [email protected] Writing and editing: Kenna Bruner, Leah Carlson (’09), Elisa Dalton Design and production: Mike Campbell and Amy Miller Photography: Glenn Asakawa, Casey A. Cass, Elisa Dalton Project management: Kimberly Warner The University of Colorado does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national ori- gin, sex, age, disability, creed, religion, sexual orientation, or veteran status in admission and access to, and treatment and employment in, its educational programs and activities. 502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/8/08 11:02 AM Page 3 2 FROM THE DEAN The Entrepreneurial Spirit 3 ENTREPRENEURS LEADING THE WAY Alumni Ventures Outside the Legal Profession 15 FACULTY EDITORIAL CEO Pay at a Time of Crisis 16 LAW SCHOOL NEWS $5M Gift for Schaden Chair 16 How Does Colorado Law Compare? 19 Academic Partnerships 20 21 LAW SCHOOL EVENTS Keeping Pace and Addressing Issues 21 Serving Diverse Communities 22 25 FACULTY HIGHLIGHTS Teaching Away from Colorado Law 25 Speaking Out 26 Schadens present Books 28 largest gift in Colorado Board Appointments 29 Law history — the Schaden Chair in 31 HONOR ROLL Experiential Learning. -

To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look for Assistance:” Confederate Welfare in Mississippi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 "To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi Lisa Carol Foster University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Foster, Lisa Carol, ""To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi" (2017). Master's Theses. 310. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/310 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster August 2017 Approved by: _________________________________________ Dr. Susannah Ural, Committee Chair Professor, History _________________________________________ Dr. Chester Morgan, Committee