Federal Judicial Center ~ @)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliography for the United States Courts of Appeals

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1994 A Bibliography for the United States Courts of Appeals Thomas E. Baker Florida International University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Thomas E. Baker, A Bibliography for the United States Courts of Appeals , 25 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 335 (1994). Available at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications/152 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BmLIOGRAPHY FOR THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS· by Thomas E. Baker" If we are to keep our democracy, there must be one commandment: Thou shalt not ration justice. - Learned Handl This Bibliography was compiled for a book by the present author entitled, RATIONING JUSTICE ON ApPEAL - THE PROBLEMS OF THE V.S. COURTS OF APPEALS, published in 1994 by the West Publishing Company. That book is a general inquiry into the question whether the United States Courts of Appeals have broken Judge Hand's commandment already and, if not, whether the Congress and the Courts inevitably will be forced to yield to the growing temptation to ration justice on appeal. After a brief history of the intermediate federal courts, the book describes the received tradition and the federal appellate ideal. The book next explains the "crisis in volume," the consequences from the huge docket growth experienced in the Courts of Appeals since the 1960s and projected to continue for the foreseeable future. -

U.S. Judicial Branch 192 U.S

U.S. G OVERNMENT IN N EBRASKA 191 U.S. JUDICIAL BRANCH 192 U.S. G OVERNMENT IN NEBRASKA U.S. JUDICIAL BRANCH1 U.S. SUPREME COURT U.S. Supreme Court Building: 1 First St. N.E., Washington, D.C. 20543, phone (202) 479-3000 Chief Justice of the United States: John G. Roberts, Jr. Article III, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution provides that “the judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” The Supreme Court is composed of the chief justice of the United States and such number of associate justices as may be fi xed by Congress. The current number of associate justices is eight. The U.S. president nominates justices, and appointments are made with the advice and consent of the Senate. Article III, Section 1, further provides that “the Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offi ces during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Offi ce.” A justice may retire at age 70 after serving for 10 years as a federal judge or at age 65 after serving 15 years. The term of the court begins, by law, the fi rst Monday in October of each year and continues as long as the business before the court requires, usually until the end of June. Six members constitute a quorum. The court hears about 7,000 cases during a term. -

Federal Criminal Litigation in 20/20 Vision Susan Herman

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 2009 Federal Criminal Litigation in 20/20 Vision Susan Herman Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation 13 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 461 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. FEDERAL CRIMINAL LITIGATION IN 20/20 VISION by Susan N. Herman* In this Article, the author examines three snapshots of the history of criminal litigation in the federal courts, from the years 1968, 1988, and 2008, with a view to predicting the future course of federal criminal adjudication. The author examines three different aspects offederal criminal litigation at these different points in time: 1) the volume and nature offederal criminal cases, 2) constitutional criminal procedure rules, and 3) federal sentencing, highlighting trends and substantial changes in each of those areas. Throughout the Article, the author notes the ways in which the future of federal criminal litigation greatly depends upon the politics of the future, includingpotential nominations to thefederal judiciary by President Barack Obama. I. IN T RO D U CT IO N ................................................................................ 461 II. CRIM INAL ADJUDICATION .............................................................. 462 III. CONSTITUTIONAL CRIMINAL PROCEDURE ............................... 467 IV. SE N T EN C IN G ...................................................................................... 469 V. C O N C LU SIO N ..................................................................................... 471 I. INTRODUCTION This Article was adapted from a speech given at the 40th anniversary celebration of the Federal Judicial Center, hosted by Lewis & Clark Law School in September, 2008, to congratulate the Federal Judicial Center on forty years of excellent work. -

March 15, 1988

REPORT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE JLlDlClAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES March 15, 1988 The Judicial Conference of the United States convened on March 15, 1988, pursuant to the call of the Chief Justice of the United States issued under 28 U.S.C. 331. The Chief Justice presided and the following members of the Conference were present: I First Circuit: Chief Judge Levin H. Campbell Chief Judge Juan M. Perez-Gimenez, District of Puerto Rico Second Circuit: Chief Judge Wilfred Feinberg Chief Judge John T. Curtin, Western District of New York Third Circuit: Chief Judge John J. Gibbons Chief Judge William J. Nealon, Jr., Middle District of Pennsylvania Fourth Circuit: L I Chief Judge Harrison L. Winter Judge Frank A. Kaufman, District of Maryland I Fifth Circuit: Chief Judge Charles Clark Chief Judge L. T. Senter, Jr., Northern District of Mississippi Sixth Circuit: Chief Judge Pierce Lively Chief Judge Phillip Pratt, Eastern District of Michigan Seventh Circuit: Chief Judge William J. Bauer Judge Sarah Evans Barker, Southern District of Indiana Eighth Circuit: Judge Gerald W. Heaney' Chief Judge John F. Nangle, Eastern District of Missouri Ninth Circuit: Chief Judge James R. Browning Chief Judge Robert F. Peckham, Northern District of California Tenth Circuit: Chief Judge William J. Holloway Chief Judge Sherman G. Finesilver, District of Colorado Eleventh Circuit: Chief Judge Paul H. Roney Chief Judge Sam C. Pointer, Jr., Northern District of Alabama District of Columbia Circuit: Chief Judge Patricia M. Wald Chief Judge Aubrey E. Robinson, Jr., District of Columbia *Designated by the Chief Justice in place of Chief Judge Donald P. -

Congressional Record—Senate S9886

S9886 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE September 21, 2006 States to offer instate tuition to these prehensive solution to the problem of communities where it is very tough to students. It is a State decision. Each illegal immigration must include the succeed, they turn their backs on State decides. It would simply return DREAM Act. crime, drugs, and all the temptations to States the authority to make that The last point I make is this: We are out there and are graduating at the top decision. asked regularly here to expand some- of their class, they come to me and It is not just the right thing to do, it thing called an H–1B visa. An H–1B visa say: Senator, I want to be an Amer- is a good thing for America. It will is a special visa given to foreigners to ican; I want to have a chance to make allow a generation of immigrant stu- come to the United States to work be- this a better country. This is my home. dents with great potential and ambi- cause we understand that in many They ask me: When are you going to tion to contribute fully to America. businesses and many places where peo- pass the DREAM Act? I come back here According to the Census Bureau, the ple work—hospitals and schools and and think: What have I done lately to average college graduate earns $1 mil- the like—there are specialties which help these young people? lion more in her or his lifetime than we need more of. -

Federal Sentencing Reform Jon O

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Howard and Iris Kaplan Memorial Lecture Lectures 4-23-2003 Federal Sentencing Reform Jon O. Newman Senior Judge for the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/lectures_kaplan Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Newman, Jon O., "Federal Sentencing Reform" (2003). Howard and Iris Kaplan Memorial Lecture. 19. http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/lectures_kaplan/19 This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Lectures at Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Howard and Iris Kaplan Memorial Lecture by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOFSTRA UNNERSITY 5ci-rOOLOF lAW 2002-2003 Howard and Iris Kaplan Memorial Lecture Series The Honorable Jon 0. Newman Senior Judge, Un ited States Co urt of Appeals for the Second Circuit JON 0 . NEWMAN j on 0. Newman is a Senior Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for th e Second Circuit (Connecticut, New York and Vennont.), on which he has served since june 1979. He was Chief judge of the Second Circuit from july 1993 to June 1997, and he served as a United States District judge for the Distri ct of Connecti cut from j anuary 1972 until his appointment to th e Court of Appeals. judge Newman graduated from Princeton University in 1953 and from Yale Law School in 1956. -

CSCHS News Spring/Summer 2015

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2015 Righting a WRong After 125 Years, Hong Yen Chang Becomes a California Lawyer Righting a Historic Wrong The Posthumous Admission of Hong Yen Chang to the California Bar By Jeffrey L. Bleich, Benjamin J. Horwich and Joshua S. Meltzer* n March 16, 2015, the 2–1 decision, the New York Supreme California Supreme Court Court rejected his application on Ounanimously granted Hong the ground that he was not a citi- Yen Chang posthumous admission to zen. Undeterred, Chang continued the State Bar of California. In its rul- to pursue admission to the bar. In ing, the court repudiated its 125-year- 1887, a New York judge issued him old decision denying Chang admission a naturalization certificate, and the based on a combination of state and state legislature enacted a law per- federal laws that made people of Chi- mitting him to reapply to the bar. The nese ancestry ineligible for admission New York Times reported that when to the bar. Chang’s story is a reminder Chang and a successful African- of the discrimination people of Chi- American applicant “were called to nese descent faced throughout much sign for their parchments, the other of this state’s history, and the Supreme students applauded each enthusiasti- Court’s powerful opinion explaining cally.” Chang became the only regu- why it granted Chang admission is Hong Yen Chang larly admitted Chinese lawyer in the an opportunity to reflect both on our United States. state and country’s history of discrimination and on the Later Chang applied for admission to the Califor- progress that has been made. -

Becoming Chief Justice: the Nomination and Confirmation Of

Becoming Chief Justice: A Personal Memoir of the Confirmation and Transition Processes in the Nomination of Rose Elizabeth Bird BY ROBERT VANDERET n February 12, 1977, Governor Jerry Brown Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office. It was an announced his intention to nominate Rose exciting opportunity: I would get to assist in the trials of OElizabeth Bird, his 40-year-old Agriculture & criminal defendants as a bar-certified law student work- Services Agency secretary, to be the next Chief Justice ing under the supervision of a public defender, write of California, replacing the retiring Donald Wright. The motions to suppress evidence and dismiss complaints, news did not come as a surprise to me. A few days earlier, and interview clients in jail. A few weeks after my job I had received a telephone call from Secretary Bird asking began, I was assigned to work exclusively with Deputy if I would consider taking a leave of absence from my posi- Public Defender Rose Bird, widely considered to be the tion as an associate at the Los Angeles law firm, O’Mel- most talented advocate in the office. She was a welcom- veny & Myers, to help manage her confirmation process. ing and supportive supervisor. That confirmation was far from a sure thing. Although Each morning that summer, we would meet at her it was anticipated that she would receive a positive vote house in Palo Alto and drive the short distance to the from Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, who would San Jose Civic Center in Rose’s car, joined by my co-clerk chair the three-member for the summer, Dick Neuhoff. -

Lower Courts of the United States

68 U.S. GOVERNMENT MANUAL include the Administrative Assistant to of procedure to be followed by the the Chief Justice, the Clerk, the Reporter lower courts of the United States. of Decisions, the Librarian, the Marshal, Court Term The term of the Court the Director of Budget and Personnel, begins on the first Monday in October the Court Counsel, the Curator, the and lasts until the first Monday in Director of Data Systems, and the Public October of the next year. Approximately 8,000 cases are filed with the Court in Information Officer. the course of a term, and some 1,000 Appellate Jurisdiction Appellate applications of various kinds are filed jurisdiction has been conferred upon the each year that can be acted upon by a Supreme Court by various statutes under single Justice. the authority given Congress by the Access to Facilities The Supreme Court Constitution. The basic statute effective is open to the public from 9 a.m. to 4:30 at this time in conferring and controlling p.m., Monday through Friday, except on jurisdiction of the Supreme Court may Federal legal holidays. Unless the Court be found in 28 U.S.C. 1251, 1253, or Chief Justice orders otherwise, the 1254, 1257–1259, and various special Clerk’s office is open from 9 a.m. to 5 statutes. Congress has no authority to p.m., Monday through Friday, except on change the original jurisdiction of this Federal legal holidays. The library is Court. open to members of the bar of the Court, Rulemaking Power Congress has from attorneys for the various Federal time to time conferred upon the departments and agencies, and Members Supreme Court power to prescribe rules of Congress. -

A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: a Century of Service

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 1 2007 A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2303 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Cover Page Footnote * This article is dedicated to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman appointed ot the U.S. Supreme Court. Although she is not a graduate of our school, she received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Fordham University in 1984 at the dedication ceremony celebrating the expansion of the Law School at Lincoln Center. Besides being a role model both on and off the bench, she has graciously participated and contributed to Fordham Law School in so many ways over the past three decades, including being the principal speaker at both the dedication of our new building in 1984, and again at our Millennium Celebration at Lincoln Center as we ushered in the twenty-first century, teaching a course in International Law and Relations as part of our summer program in Ireland, and participating in each of our annual alumni Supreme Court Admission Ceremonies since they began in 1986. -

An Empirical Study of the Ideologies of Judges on the Unites States

JUDGED BY THE COMPANY YOU KEEP: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE IDEOLOGIES OF JUDGES ON THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS Corey Rayburn Yung* Abstract: Although there has been an explosion of empirical legal schol- arship about the federal judiciary, with a particular focus on judicial ide- ology, the question remains: how do we know what the ideology of a judge actually is? For federal courts below the U.S. Supreme Court, legal aca- demics and political scientists have offered only crude proxies to identify the ideologies of judges. This Article attempts to cure this deficiency in empirical research about the federal courts by introducing a new tech- nique for measuring the ideology of judges based upon judicial behavior in the U.S. courts of appeals. This study measures ideology, not by subjec- tively coding the ideological direction of case outcomes, but by determin- ing the degree to which federal appellate judges agree and disagree with their liberal and conservative colleagues at both the appellate and district court levels. Further, through regression analysis, several important find- ings related to the Ideology Scores emerge. First, the Ideology Scores in this Article offer substantial improvements in predicting civil rights case outcomes over the leading measures of ideology. Second, there were very different levels and heterogeneity of ideology among the judges on the studied circuits. Third, the data did not support the conventional wisdom that Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush appointed uniquely ideological judges. Fourth, in general judges appointed by Republican presidents were more ideological than those appointed by Democratic presidents. -

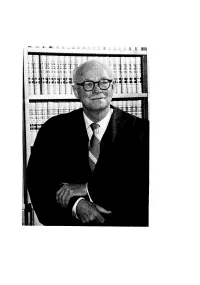

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R. BROWN John R. Brown is a native Nebraskan. He was born in the town of Holdredge on December 10, 1909. Judge Brown remained in Ne- braska through his undergraduate education and received an A.B. degree in 1930 from the University of Nebraska. The Judge's legal education was attained at the University of Michigan, from which he received a J.D. degree in 1932. Both of Judge Brown's alma maters have conferred upon him Honorary LL.D. degrees. The University of Michigan did so in 1959, followed by the University of Nebraska in 1965. During World War II, the Judge served in the United States Air Force. Judge Brown was appointed to the United States Court of Ap- peals by President Eisenhower in July, 1955. Twelve years later, in July, 1967, he became Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Since 1967 the Judge has represented the Fifth Circuit at the Judicial Conference of the United States, as well as having been a member of its executive committee since 1972. The Judge is also a member of the Houston Bar Association, the Texas Bar Association, the American Bar Association, and the Maritime Law Association of the United States. Judge Brown is married to the former Mary Lou Murray and has one son, John R., Jr. The Judge currently lives in Houston. i, iiI IVA JUDGE RICHARD T. RIVES Richard T. Rives was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on Janu- ary 15, 1895. He attended Tulane University in the years 1911 and 1912.