Genuflect, Gentlemen and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trademark Law and the Prickly Ambivalence of Post-Parodies

8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE) 8/28/2014 3:07 PM ESSAY TRADEMARK LAW AND THE PRICKLY AMBIVALENCE OF POST-PARODIES CHARLES E. COLMAN† This Essay examines what I call “post-parodies” in apparel. This emerging genre of do-it-yourself fashion is characterized by the appropriation and modification of third-party trademarks—not for the sake of dismissively mocking or zealously glorifying luxury fashion, but rather to engage in more complex forms of expression. I examine the cultural circumstances and psychological factors giving rise to post-parodic fashion, and conclude that the sensibility causing its proliferation is grounded in ambivalence. Unfortunately, current doctrine governing trademark “parodies” cannot begin to make sense of post-parodic goods; among other shortcomings, that doctrine suffers from crude analytical tools and a cramped view of “worthy” expression. I argue that trademark law—at least, if it hopes to determine post-parodies’ lawfulness in a meaning ful way—is asking the wrong questions, and that existing “parody” doctrine should be supplanted by a more thoughtful and nuanced framework. † Acting Assistant Professor, New York University School of Law. I wish to thank New York University professors Barton Beebe, Michelle Branch, Nancy Deihl, and Bijal Shah, as well as Jake Hartman, Margaret Zhang, and the University of Pennsylvania Law Review Editorial Board for their assistance. This piece is dedicated to Anne Hollander (1930–2014), whose remarkable scholarship on dress should be required reading for just about everyone. (11) 8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE)8/28/2014 3:07 PM 12 University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online [Vol. -

4557 Deep Int CC.Indd

“The story of these women touched the deep places in my heart. The threads of God’s grace are evident in this story, weaving together women of strength and devotion who, above all, need the gift of grace. An excep- tional read and one that will live with me long after I close the book.” —Jaime Jo Wright, best-selling author of The House on Foster Hilland The Reckoning at Gossamer Pond “Swimming in the Deep End is a heart-touching tale of four women who have each suffered the wrenching loss of a child. With a rare warmth and Christlike attitude, Nelson unfolds their personal tragedies and taps into our souls as unbridled emotions and past wounds spill out of these char- acters’ lives into our own. They must work together to surmount impos- sible challenges, and their inspiring selflessness is all for the good of an innocent child. A moving read guaranteed to evoke sad as well as happy tears, you won’t soon forget this book!” —Marilyn Rhoads, president of Oregon Christian Writers Praise for Christina Suzann Nelson “If you love discovering new authors with a lyrical, literary voice, then you’re in for a treat. If you like those voices to also deliver a powerful, engaging story with true emotional depth, then you’re in for a feast. Highly recommended.” —James L. Rubart, best-selling author of The Five Times I Met Myself and The Long Journey to Jake Palmer “A tension-filled tour de force of suspense and human emotions.” —Library Journal, starred review “Nelson skillfully draws readers into character emotions in a way that sets us up for what lies ahead. -

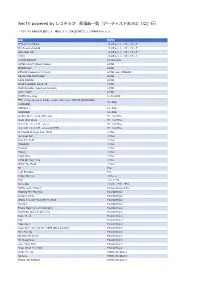

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

The Palm-Up Puzzle: Meanings and Origins of a Widespread Form in Gesture and Sign

REVIEW published: 26 June 2018 doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00023 The Palm-Up Puzzle: Meanings and Origins of a Widespread Form in Gesture and Sign Kensy Cooperrider 1*, Natasha Abner 2 and Susan Goldin-Meadow 1 1 Department of Psychology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States, 2 Department of Linguistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States During communication, speakers commonly rotate their forearms so that their palms turn upward. Yet despite more than a century of observations of such palm-up gestures, their meanings and origins have proven difficult to pin down. We distinguish two gestures within the palm-up form family: the palm-up presentational and the palm-up epistemic. The latter is a term we introduce to refer to a variant of the palm-up that prototypically involves lateral separation of the hands. This gesture—our focus—is used in speaking communities around the world to express a recurring set of epistemic meanings, several of which seem quite distinct. More striking, a similar palm-up form is used to express the same set of meanings in many established sign languages and in emerging sign Edited by: systems. Such observations present a two-part puzzle: the first part is how this set of Marianne Gullberg, Lund University, Sweden seemingly distinct meanings for the palm-up epistemic are related, if indeed they are; the Reviewed by: second is why the palm-up form is so widely used to express just this set of meanings. We Gaelle Ferre, propose a network connecting the different attested meanings of the palm-up epistemic, University of Nantes, France with a kernel meaning of absence of knowledge, and discuss how this proposal could be Maria Graziano, Lund University, Sweden evaluated through additional developmental, corpus-based, and experimental research. -

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I Feel Like I Am Always Running from Someone

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I feel like I am always running from someone. I can feel their eyes watching me. My name is Bella Swan; I am 16 years old and a sophomore in high school. My father is Charlie Swan is Mafia lord and his best friend Carlisle Cullen is his partner in crime who I have heard a lot about over the years. My mother is Renee Swan she is definitely one the sweetest mother's in the world but she can be your worst nightmare if you get on her bad side. I have four older siblings Sam, Jacob, Rose, and Alice. I am the baby of the family which also means I get the most unwanted attention and my siblings have a hard time accepting that I'm not a little girl anymore, I am almost an adult. My ex-boyfriend Chris was murdered when I was 15 years old. He was definitely the sweetest boyfriend you could have, I loved him and wanted to marry him in the future, but that will never happen with him. Many people want me for my families' money, but he wanted me for who I was. The mafia life is what I grew up with living in New York; I learned you can't trust anyone outside of the family except for the Cullen's. I also didn't trust people because of what I had dealt with the past sixteen years. Which brings me here in Chicago at Mr. Cullen's house, my father announced to me last week that I was arranged to be married to Mr. -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

Meeting Packet

Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting Date and Time Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM EDT Notice of this meeting was posted on the ANCS website and both ANCS campuses in accordance with O.C.G.A. § 50-14-1. Agenda Purpose Presenter Time I. Opening Items 6:30 PM Opening Items A. Record Attendance and Guests Kristi 1 m Malloy B. Call the Meeting to Order Lee Kynes 1 m C. Brain Smart Start Mark 5 m Sanders D. Public Comment 5 m E. Approve Minutes from Prior Board Meeting Approve Kristi 3 m Minutes Malloy Approve minutes for ANCS Governing Board Meeting on June 21, 2021 F. PTCA President Update Rachel 5 m Ezzo G. Principals' Open Forum Cathey 10 m Goodgame & Lara Zelski Standing monthly opportunity for ANCS principals to share highlights from each campus. II. Executive Director's Report 7:00 PM A. Executive Director Report FYI Chuck 20 m Meadows Powered by BoardOnTrack 1 of1 of393 2 Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School - ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting - Agenda - Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM Purpose Presenter Time III. DEAT Update 7:20 PM A. Monthly DEAT Report FYI Carla 5 m Wells IV. Finance & Operations 7:25 PM A. Monthly Finance & Operations Report Discuss Emily 5 m Ormsby B. Vote on 2021-2022 Financial Resolution Vote Emily 10 m Ormsby V. Governance 7:40 PM A. Monthly Governance Report FYI Rhonda 5 m Collins B. Vote on Committee Membership Vote Lee Kynes 5 m C. Vote on Nondiscrimination & Parental Leave Vote Rhonda 10 m Policies Collins D. -

California VOL

california VOL. 73 NO.Apparel 29 NewsJULY 10, 2017 $6.00 2018 Siloett Gets a WATERWEAR Made-for-TV Makeover TEXTILE Tori Praver Swims TRENDS In the Pink in New Direction Black & White Stay Gold Raj, Sports Illustrated Team Up TRENDS Cruise ’18— Designer STREET STYLE Viewpoint Venice Beach NEW RESOURCES Drupe Old Bull Lee Horizon Swim Z Supply 01.cover-working.indd 2 7/3/17 6:39 PM APPAREL NEWS_jan2017_SAF.indd 1 12/7/16 6:23 PM swimshowmiami.indd 1 12/27/16 2:41 PM SWIM COLLECTIVE BOOTH 528 MIAMI SHOW BOOTH 224 HALL B SURF EXPO BOOTH 3012 Sales Inquiries 1.800.463.7946 [email protected] • seaandherswim.com seaher.indd 1 6/28/17 2:30 PM thaikila.indd 4 6/23/17 11:56 AM thaikila.indd 5 6/23/17 11:57 AM JAVITS CENTER MANDALAY BAY NEW! - HALL 1B CONVENTION CENTER AUGUST SUN 06 MON 14 MON 07 TUES 15 TUES 08 WED 16 SPRING SUMMER 2018 www.eurovetamericas.com info@curvexpo | +1.212.993.8585 curve_resedign.indd 1 6/30/2017 9:39:24 AM curvexpo.indd 1 6/30/17 9:32 AM mbw.indd 1 7/6/17 2:24 PM miraclesuit.com magicsuitswim.com 212-730-9555 aandhswim.indd 6 6/28/17 2:13 PM creora® Fresh odor neutralizing spandex for fresh feeling. creora® highcloTM super chlorine resistant spandex for lasting fit and shape retention. Outdoor Retailer Show 26-29 July 2017 Booth #255-313 www.creora.com creora® is registered trade mark of the Hyosung Corporation for its brand of premium spandex. -

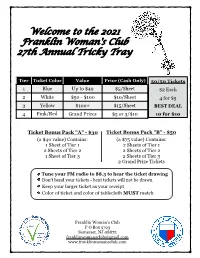

Hered White Frame for 5X7 Photo, 4X6 Slide 30

Welcome to the 2021 Franklin Woman's Club 27th Annual Tricky Tray Tier Ticket Color Value Price (Cash Only) 50/50 Tickets 1 Blue Up to $49 $5/Sheet $2 Each 2 White $50 - $100 $10/Sheet 4 for $5 3 Yellow $100+ $15/Sheet BEST DEAL 4 Pink/Red Grand Prizes $5 or 3/$10 10 for $10 Ticket Bonus Pack "A" - $30 Ticket Bonus Pack "B" - $50 (a $40 value) Contains: (a $75 value) Contains: 1 Sheet of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 2 2 Sheets of Tier 2 1 Sheet of Tier 3 2 Sheets of Tier 3 2 Grand Prize Tickets Tune your FM radio to 88.3 to hear the ticket drawing Don't bend your tickets - bent tickets will not be drawn Keep your larger ticket as your receipt Color of ticket and color of tablecloth MUST match Franklin Woman's Club P O Box 5793 Somerset, NJ 08875 [email protected] www.franklinwomansclub.com 11. Desk Set #1 Tier 1 Prizes 12. Desk Set #2 (Blue Tickets; Value up to $49) Black mesh letter sorter, pencil cup, clip holder and wastebasket 1. Cherry Blossom Spa Basket 13. Cake Pop Crush Japanese Cherry Blossom shower gel, bubble Cake Pops baking pan & accessories, cake pop bath, flower bath pouf, bath bombs, body and sticks, youth books “Cake Pop Crush” and hand lotion, more “Taking the Cake" 2. Friend Frame 14. Lunch Break "Friends" 6-opening photo collage picture frame FILA insulated lunch bag, pair of small snack for 2.25 X 3.25 inch photos containers 3. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

November 4, 2010

Serving James Madison University Since 1922 Rain 51°/ 40° Vol. 87, No. 20 chance of precipitation: 90% Thursday, November 4, 2010 The Breeze is HIRING a This decision was one ... new OPINION EDITOR. Apply made by me, not for me at joblink.jmu.edu Multiple incidents over Halloween “ weekend Charges still fewer than last year’s numbers ” Two men allegedly involved in sepa- rate incidents over Halloween weekend are both scheduled to appear in Rock- ingham/Harrisonburg General District Court on Nov. Mario Dominic Wright, , was charged with a felony count of rearm larceny, a felony count of grand larceny, a misdemeanor count of brandishing a RYAN FREELAND / THE BREEZE gun and a misdemeanor count of unlaw- Brock Wallace, senior and former vice president of Student Affairs, stepped down instead of facing impeachment at Tuesday’s SGA meeting. ful possession of alcohol, according to court records. Police responded to a call at about : SGA executive resigns, committee to investigate Purple Out T-shirt distribution a.m. Sunday in Fox Hills Townhomes, according to Harrisonburg police By KATIE THISDELL and T-shirt distribution and the Mr. and Ms. Elwell said that some senators had heard spokeswoman Mary-Hope Vass. Wright, AMANDA CASKEY Madison competition. rumors about early distribution of T-shirts, who is not a JMU student, had alcohol The Breeze SGA president Andrew Reese said he which has traditionally been a highly antic- with him and was waving a gun around, was “pleasantly surprised,” as he had ipated event. according to witness reports Vass said. As the Student Government Association asked Wallace to resign upon learning of “I’ve heard several things, other people Nearby individuals pointed him out to prepares for a special election to ll a now- his charges about two weeks ago.