The Normal Review, a Literary and Arts Publication, Fall 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Descriptive and Comparative Study of Conceptual Metaphors in Pop and Metal Lyrics

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y HUMANIDADES DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA METAPHORS WE SING BY: A DESCRIPTIVE AND COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CONCEPTUAL METAPHORS IN POP AND METAL LYRICS. Informe final de Seminario de Grado para optar al Grado de Licenciado en Lengua y Literatura Inglesas Estudiantes: María Elena Álvarez I. Diego Ávila S. Carolina Blanco S. Nelly Gonzalez C. Katherine Keim R. Rodolfo Romero R. Rocío Saavedra L. Lorena Solar R. Manuel Villanovoa C. Profesor Guía: Carlos Zenteno B. Santiago-Chile 2009 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Professor Carlos Zenteno for his academic encouragement and for teaching us that [KNOWLEDGE IS A VALUABLE OBJECT]. Without his support and guidance this research would never have seen the light. Also, our appreciation to Natalia Saez, who, with no formal attachment to our research, took her own time to help us. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Guillermo Soto, whose suggestions were fundamental to the completion of this research. Degree Seminar Group 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Gracias a mi mamá por todo su apoyo, por haberme entregado todo el amor que una hija puede recibir. Te amo infinitamente. A la Estelita, por sus sabias palabras en los momentos importantes, gracias simplemente por ser ella. A mis tías, tío y primos por su apoyo y cariño constantes. A mis amigas de la U, ya que sin ellas la universidad jamás hubiese sido lo mismo. Gracias a Christian, mi compañero incondicional de este viaje que hemos decidido emprender juntos; gracias por todo su apoyo y amor. A mi abuelo, que me ha acompañado en todos los momentos importantes de mi vida… sé que ahora estás conmigo. -

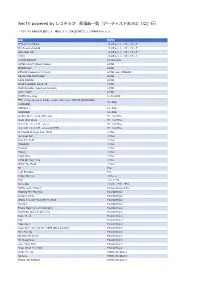

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I Feel Like I Am Always Running from Someone

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I feel like I am always running from someone. I can feel their eyes watching me. My name is Bella Swan; I am 16 years old and a sophomore in high school. My father is Charlie Swan is Mafia lord and his best friend Carlisle Cullen is his partner in crime who I have heard a lot about over the years. My mother is Renee Swan she is definitely one the sweetest mother's in the world but she can be your worst nightmare if you get on her bad side. I have four older siblings Sam, Jacob, Rose, and Alice. I am the baby of the family which also means I get the most unwanted attention and my siblings have a hard time accepting that I'm not a little girl anymore, I am almost an adult. My ex-boyfriend Chris was murdered when I was 15 years old. He was definitely the sweetest boyfriend you could have, I loved him and wanted to marry him in the future, but that will never happen with him. Many people want me for my families' money, but he wanted me for who I was. The mafia life is what I grew up with living in New York; I learned you can't trust anyone outside of the family except for the Cullen's. I also didn't trust people because of what I had dealt with the past sixteen years. Which brings me here in Chicago at Mr. Cullen's house, my father announced to me last week that I was arranged to be married to Mr. -

![[Daniel, 14, Santiago, Chile] Vision Fr Movemen N T](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9364/daniel-14-santiago-chile-vision-fr-movemen-n-t-669364.webp)

[Daniel, 14, Santiago, Chile] Vision Fr Movemen N T

2002 [Daniel, 14, Santiago, Chile] vision fr movemen n t oceans ancient forests climate toxics nuclear power and disarmament genetic engineering [featuring year 2001 financial statements] 2001financial year [featuring [Bill Nandris, one of the‘Star Wars 17’] 1 greenpeace 2002 brunt of environmental degradation of environmental brunt It is the poor that normally bear the It is the poor that normally “ shatter spirit In Brazil, with great The situation is serious, but Summit’s innovative economics and the actions fanfare, governments set not hopeless. On the plus Agenda 21 – millions of of states are pulling in a out on the ‘road to side, the past decade has people around the world quite different direction. sustainability’. But most of seen the adoption of are tackling local Individuals, businesses and them have now ground to a significant environmental environmental issues with countries have a choice. halt, mired in inaction and legislation at national and dedication, energy and no We can have limitless cars As I write this, final preparations are underway for the Earth Summit in Johannesburg. in Summit Earth the for underway are this, preparations write final I As a return to ‘business as international levels and an small measure of expertise. and computers, plastics usual’.The road from Rio is increasing ecological In schools, children from and air-freighted knee-deep in shattered awareness among policy virtually every country are vegetables, but in exchange promises, not least the makers and scientists. learning about the we get Bhopal and craven caving-in by the But perhaps most environment and its Chernobyl, species USA to the interests of the significant of all is the importance for their future. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

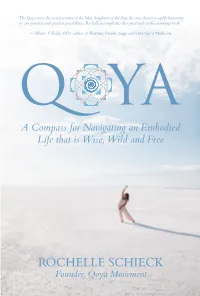

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

THE TALL MAN's GUESTBOOK December 2001

25 March 2005 Jeff Weise writings, retrieved via Google on March 24, 2005. Blades11 on The Tall Man's Guest Book Blades11 on EZ Board's The Writer's Coven Blades11 on Dune2K Blades11 on Raptorman See also Jeff Weise postings on Nazi.org: http://cryptome.sabotage.org/jeff-weise.htm As Blades11 on The Tall Man's Guest Book THE TALL MAN'S GUESTBOOK December 2001 It takes some big balls to speak up to the big guy! Comments list started on December 1, 2001 Last post on December 31, 2001 Blades11, Redlake,MN Sat Dec 1 23:06:05 EST 2001 P1: Yes P2: Yes P3: Yes P4: Yes Ok,I am writing about the e-mail. To me it seem's to be a sort of Fan fiction.Are some body hoping to make people wonder if the movie's were real.That is what I believe.As for the Phantasm series?,I LOVE IT!. My Fav's P3,But they are all cool....Love the site,I'd like to see still's from P3..... But that's just me.... -Blades11 As Blades11 on http://p090.ezboard.com/fthedeadwalkfrm10 Source: http://p081.ezboard.com/bwriterscoven.showUserPublicProfile?gid=blades11 Blades11 Total Posts :: 772 Member Since :: October 8, 2001 (Global User) My Personal Information First Name :: private Last Name :: private Age :: 17 Location :: .:Minnesota:. Occupation :: .:Amateur Writer:. Hobbies :: Writing, drawing, listening to music, chatting/hanging out with friend's, playing guitar, and animating. Personal Bio :: I'm a fan of zombie film's, have been for year's, as well as fan of horror movies in general. -

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1Wayfrank Ayegirl

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1wayfrank Ayegirl - Single Ayegirl Streaming 2017 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Best of 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Dreams (Radio Version) Streaming 2017 2 Chainz TrapAvelli Tre El Chapo Jr Streaming 2017 2 Unlimited Get Ready for This - Single Get Ready for This (Yar Rap Edit) Streaming 2017 3LAU Fire (Remixes) - Single Fire (Price & Takis Remix) Streaming 2017 4Pro Smiler Til Fjender - Single Smiler Til Fjender Streaming 2017 666 Supa-Dupa-Fly (Remixes) - EP Supa-Dupa-Fly (Radio Version) Lets Lurk (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Streaming 2017 67 Liquez) No Hook (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Liquez) Streaming 2017 6LACK Loyal - Single Loyal Streaming 2017 8Ball Julekugler - Single Julekugler Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 Behøver ikk Behøver ikk (feat. Milo) Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 DE VED DET DE VED DET Streaming 2017 A Billion Robots This Is Melbourne - Single This Is Melbourne Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember Homesick (Special Edition) If It Means a Lot to You Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember What Separates Me from You All I Want Streaming 2017 A Flock of Seagulls Wishing: The Very Best Of I Ran Streaming 2017 A.CHAL Welcome to GAZI Round Whippin' Streaming 2017 A2M I Got Bitches - Single I Got Bitches Streaming 2017 Abbaz Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig - Single Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig Streaming 2017 Abbaz Harakat (feat. Gio) - Single Harakat (feat. Gio) Streaming 2017 ABRA Rose Fruit Streaming 2017 Abstract Im Good (feat. Roze & Drumma Battalion) Im Good (feat. Blac) Streaming 2017 Abstract Something to Write Home About I Do This (feat. -

Songliste Koreanisch (Juli 2018) Sortiert Nach Interpreten

Songliste Koreanisch (Juli 2018) Sortiert nach Interpreten SONGCODETITEL Interpret 534916 그저 널 바라본것 뿐 1730 534541 널 바라본것 뿐 1730 533552 MY WAY - 533564 기도 - 534823 사과배 따는 처녀 - 533613 사랑 - 533630 안녕 - 533554 애모 - 533928 그의 비밀 015B 534619 수필과 자동차 015B 534622 신인류의 사랑 015B 533643 연인 015B 975331 나 같은 놈 100% 533674 착각 11월 975481 LOVE IS OVER 1AGAIN 980998 WHAT TO DO 1N1 974208 LOVE IS OVER 1SAGAIN 970863기억을 지워주는 병원2 1SAGAIN/FATDOO 979496 HEY YOU 24K 972702 I WONDER IF YOU HURT LIKE ME 2AM 975815 ONE SPRING DAY 2AM 575030 죽어도 못 보내 2AM 974209 24 HOUR 2BIC 97530224소시간 2BIC 970865 2LOVE 2BORAM 980594 COME BACK HOME 2NE1 980780 DO YOU LOVE ME 2NE1 975116 DON'T STOP THE MUSIC 2NE1 575031 FIRE 2NE1 980915 HAPPY 2NE1 980593 HELLO BITCHES 2NE1 575032 I DON'T CARE 2NE1 973123 I LOVE YOU 2NE1 975236 I LOVE YOU 2NE1 980779 MISSING YOU 2NE1 976267 UGLY 2NE1 575632 날 따라 해봐요 2NE1 972369 AGAIN & AGAIN 2PM Seite 1 von 58 SONGCODETITEL Interpret 972191 GIVE IT TO ME 2PM 970151 HANDS UP 2PM 575395 HEARTBEAT 2PM 972192 HOT 2PM 972193 I'LL BE BACK 2PM 972194 MY COLOR 2PM 972368 NORI FOR U 2PM 972364 TAKE OFF 2PM 972366 THANK YOU 2PM 980781 WINTER GAMES 2PM 972365 CABI SONG 2PM/GIRLS GENERATION 972367 CANDIES NEAR MY EAR 2PM/백지영 980782 24 7 2YOON 970868 LOVE TONIGHT 4MEN 980913 YOU'R MY HOME 4MEN 975105 너의 웃음 고마워 4MEN 974215 안녕 나야 4MEN 970867 그 남자 그 여자 4MEN/MI 980342 COLD RAIN 4MINUTE 980341 CRAZY 4MINUTE 981005 HATE 4MINUTE 970870 HEART TO HEART 4MINUTE 977178 IS IT POPPIN 4MINUTE 975346 LOVE TENSION 4MINUTE 575399 MUZIK 4MINUTE 972705 VOLUME UP 4MINUTE 975332 WELCOME -

SCHOOL ME a Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San

SCHOOL ME A Written Creative Work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Playwriting by Ramon S. Jackson San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Ramon Shawntez Jackson 2011 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read School Me by Ramon Shawntez Jackson, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: Playwriting at San Francisco State University. Roy Co )oy Au/D. Professd Creative Writing Michelle Carter, Au.D. Professor of Creative Writing SCHOOL ME RAMON SHAWNTEZ JACKSON San Francisco, California 2018 “School Me”: A play on words and worlds Michelle Carter and Roy Conboy (Mentors), Department of Creative Writing “School Me” is a hyper-realistic creative work that seeks to initiate conversation surrounding academic, vocabularies of communication, and the pedagogy of inclusive access for all. The setting - an Ethics 101 class full of local community college students (Laney College, Oakland.); their quest - to escape the never ending war-zones the live in for a fresh start an legal money. Their shared obstacle; an extremely detached professor, and a city on the verge of annihilation because of another murdered young black male. When will enough be enough? What are the keys to freedom? Can any of them last through the semester to graduate? Who has the vocabularies of access? This play was written as a commentary on the advanced education system and some of the short-comings I noticed as I encountered these characters. -

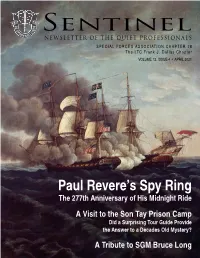

April 2021 | Sentinel 1 RETURN to TOC Paul Revere’S Spy Ring

Sentinel NEWSLETTER OF THE QUIET PROFESSIONALS SPECIAL FORCES ASSOCIATION CHAPTER 78 The LTC Frank J. Dallas Chapter VOLUME 12, ISSUE 4 • APRIL 2021 Paul Revere’s Spy Ring The 277th Anniversary of His Midnight Ride A Visit to the Son Tay Prison Camp Did a Surprising Tour Guide Provide the Answer to a Decades Old Mystery? A Tribute to SGM Bruce Long From the Editor VOLUME 12, ISSUE 4 • APRIL 2021 It feels as though the pace of life is quicken- IN THIS ISSUE: ing lately. I wonder if that is how Paul Revere Vice President’s Page ...................................................... 1 felt on that April night in ‘75. His efforts were Paul Revere’s Spy Ring ................................................... 2 something any Green Beret would be proud US ARMY SPECIAL of. His previous commo and psyops exploits OPS COMMAND A Visit to the Son Tay POW Camp — are evident in that his deliveries of messages Did a Surprising Tour Guide Provide the of top importance to the other colonies had Answer to a Decades Old Mystery? ................................ 6 already made him famous. That night his My Visit to the Son Tay POW Camp — integral role in gathering intel yielded fruit of How Miller US ARMY A memoir by S. Vaughn Binzer ........................................ 9 immediate and urgent value. And later his JFK SWCS Sentinel Editor A Tribute to SGM Bruce Long ........................................... 10 weapons and engineering skills were used SFA Chapter 78 March 2021 Chapter Meeting ...................13 to fashion cannons and outfit ships, including the USS Constitution (pictured on our cover). FRONT COVER: The USS Constitution in action. According to Patrick 1ST SF COMMAND I thought this would be a good place to start my intermittent series on Leehey, “Paul Revere provided most of the bolts, spikes, nails, pins and historical American Special Operations.