Copycat-Walk:Parody in Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trademark Law and the Prickly Ambivalence of Post-Parodies

8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE) 8/28/2014 3:07 PM ESSAY TRADEMARK LAW AND THE PRICKLY AMBIVALENCE OF POST-PARODIES CHARLES E. COLMAN† This Essay examines what I call “post-parodies” in apparel. This emerging genre of do-it-yourself fashion is characterized by the appropriation and modification of third-party trademarks—not for the sake of dismissively mocking or zealously glorifying luxury fashion, but rather to engage in more complex forms of expression. I examine the cultural circumstances and psychological factors giving rise to post-parodic fashion, and conclude that the sensibility causing its proliferation is grounded in ambivalence. Unfortunately, current doctrine governing trademark “parodies” cannot begin to make sense of post-parodic goods; among other shortcomings, that doctrine suffers from crude analytical tools and a cramped view of “worthy” expression. I argue that trademark law—at least, if it hopes to determine post-parodies’ lawfulness in a meaning ful way—is asking the wrong questions, and that existing “parody” doctrine should be supplanted by a more thoughtful and nuanced framework. † Acting Assistant Professor, New York University School of Law. I wish to thank New York University professors Barton Beebe, Michelle Branch, Nancy Deihl, and Bijal Shah, as well as Jake Hartman, Margaret Zhang, and the University of Pennsylvania Law Review Editorial Board for their assistance. This piece is dedicated to Anne Hollander (1930–2014), whose remarkable scholarship on dress should be required reading for just about everyone. (11) 8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE)8/28/2014 3:07 PM 12 University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online [Vol. -

Chilling Effects”? Takedown Notices Under Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act

Efficient Process or “Chilling Effects”? Takedown Notices Under Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Summary Report Jennifer M. Urban Director, Intellectual Property Clinic University of Southern California and Laura Quilter Non-Resident Fellow, Samuelson Clinic University of California, Berkeley Introduction This is a summary report of findings from a study of takedown notices under Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.1 Section 512 grants safe harbor from secondary copyright liability (i.e., the copyright infringement of their end users) to online service providers (OSPs), such as Internet access providers or online search engines. In order to receive the safe harbor, online service providers respond to cease-and-desist letters from copyright complainants by pulling their users’ information—web pages, forum postings, blog entries, and the like—off the Internet. (In the case of search engine providers, the link to the complained-of web site is pulled out of the index; in turn, the web site disappears from the search results pages. These notices are somewhat troubling in and of themselves, as merely providing a link is unlikely to create secondary liability for the search engine, in the first place.) Because the OSP is removing material in response to a private cease-and-desist letter that earns it a safe harbor, no court sees the dispute in advance of takedown. In this study, we traced the use of the Section 512 takedown process and considered how the usage patterns we found were likely to affect expression -

SUMMER ART INQUIRY 2018 a Resource Guide P AG a ND A

P RO SUMMER ART INQUIRY 2018 a resource guide P AG A ND A PROPAGANDA a program resource guide summer art inquiry new urban arts 2018 New Urban Arts is a nationally recognized interdisciplinary arts studio for high school students and artists in Providence, Rhode Island. Our mission is to build a vital community that empowers young people as artists and leaders, through developing creative practices they can sustain throughout their lives. We provide studio and exhibition space and mentoring for young artists who explore the visual, performing and literary arts. Founded in 1997, New Urban Arts is housed in a storefront art studio, located in the West End neighborhood of Providence. Our facilities include a gallery, darkroom, screen-printing studio, tabletop printing press, recording studio, resource library, administrative offices, computer lab and 6,000 square feet of open studio space. We serve over 500 high school students, 18 artists and over 2,000 ABOUT NEW URBAN ARTS visitors through free youth programs, professional development, artist residencies as well as public performances, workshops and exhibitions each year. NEW URBAN ARTS 705 Westminster Street, Providence, RI 02903 p 401 751 4556 f 401 273 8499 www.newurbanarts.org [email protected] 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This program resource guide was created by summer scholar, Eli Nixon, with pub- lication design by artist mentor, Dean Sudarsky, photography by Eli Nixon, Dana Heng, and Jobanny Cabrera; and editing by Emily Ustach and Sophia Mackenzie. Special thanks to our Summer Scholar, Eli Nixon for all of their guidance, and support throughout the summer. Thank you to all the visiting artists and scholars who helped us this summer including Meredith Stern, Ricky Katowicz, Dana Heng, and Ian Cozzens. -

Walking the Tightrope of Cease-And- Desist Le�Ers

ARTICLE Walking the Tightrope of Cease-and- Desist Leers June 2018 Intellectual Property & Technology Law Journal By Jason E. Stach; Nathan I. North Cease-and-desist letters, and less aggressive notice letters, can serve several purposes for patent owners. Among other things, they can open licensing negotiations, serve as warnings to competitors, create notice for damages, and establish knowledge for indirect infringement. But sending these letters can also be risky. Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s MedImmune v. Genentech decision,1 the letters may more easily create declaratory judgment (DJ) jurisdiction, allowing a potential defendant to select its preferred forum and to control the timing of an action. Despite the tension between these competing doctrines, courts have acknowledged that it is possible to send legally effective cease-and- desist letters2 while also avoiding DJ jurisdiction. To do so, patentees must carefully approach these letters to minimize risks while still achieving their goals. A closer look at these issues reveals several ways to minimize this risk. Declaratory Judgment Jurisdiction: A Look at the Totality of the Circumstances In MedImmune, the Supreme Court evaluated DJ jurisdiction under a totality-of-the-circumstances test, where there must be “a substantial controversy, between parties having adverse legal interests, of sufficient immediacy and reality to warrant relief.“3 Looking to the totality of the circumstances, courts analyze the contents of a cease-and-desist letter as a key factor—but often not the only factor—in assessing DJ jurisdiction. Other factors include the relationship of the parties, litigation history of the patent owner, actions of the parties, and more, as discussed below in the context of the MedImmune test. -

Why I Believe New York's Art Scene Is Doomed - Artnet News

1/23/2015 Why I Believe New York's Art Scene Is Doomed - artnet News artnet artnet Auctions I n Br i e f M a r k e t A r t W o r l d P e op l e Top i c s S ear ch $58 Million Trove of King Tut Damaged in New York DA Launches Supreme Court Declines Looted Antiquities Botched Repair Attempt Secret Art Sales Tax… to Hear Norton… Uncovered… Why I Believe New York's Art Scene Is Doomed Newsletter Signup B e n D a vi s , M o n d a y, J a n u a r y 1 2 , 2 0 1 5 E N T E R Y O U R E M A I L S U B M I T S H A R E Latest H eadlines First-Ever Yves Saint Laurent Exhibition Will Land on British… Piper Marshall Brings Four Solo Shows of Female Artists… Tintin Cover Art to Go on Sale for Nearly… High-wire act: Suspended Cirque performance at Galapagos Art Space Image: Courtesy Galapagos Art Space V & A to Print 50,000 More Tickets for… This is an article about art and gentrification, the inescapable topic. I have something new to add—that I think we may be coming to the end of a period where being an artist was synonymous with being urban, unless we are willing to fight for it—but before I start it, let me say that I Death of King Abdullah of Saudi have mixed feelings about my own conclusions. -

Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years Under the DMCA

Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years under the DMCA By Fred Von Lohmann, [email protected] February 2010 ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION eff.org Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years under the DMCA This document collects reported cases where the anti-circumvention provisions of the DMCA have been invoked not against pirates, but against consumers, scientists, and legitimate compet- itors. It will be updated from time to time as additional cases come to light. The latest version can always be obtained at www.eff.org. 1. Executive Summary Since they were enacted in 1998, the “anti-circumvention” provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”), codified in section 1201 of the Copyright Act, have not been used as Congress envisioned. Congress meant to stop copyright infringers from defeating anti-piracy protections added to copyrighted works and to ban the “black box” devices intended for that purpose. 1 In practice, the anti-circumvention provisions have been used to stifle a wide array of legitimate activities, rather than to stop copyright infringement. As a result, the DMCA has developed into a serious threat to several important public policy priorities: The DMCA Chills Free Expression and Scientific Research. Experience with section 1201 demonstrates that it is being used to stifle free speech and scientific research. The lawsuit against 2600 magazine, threats against Princeton Profes- sor Edward Felten’s team of researchers, and prosecution of Russian programmer Dmitry Sklyarov have chilled the legitimate activities of journalists, publishers, scientists, stu- dents, program¬mers, and members of the public. The DMCA Jeopardizes Fair Use. By banning all acts of circumvention, and all technologies and tools that can be used for circumvention, the DMCA grants to copyright owners the power to unilaterally elimi- nate the public’s fair use rights. -

Meeting Packet

Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting Date and Time Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM EDT Notice of this meeting was posted on the ANCS website and both ANCS campuses in accordance with O.C.G.A. § 50-14-1. Agenda Purpose Presenter Time I. Opening Items 6:30 PM Opening Items A. Record Attendance and Guests Kristi 1 m Malloy B. Call the Meeting to Order Lee Kynes 1 m C. Brain Smart Start Mark 5 m Sanders D. Public Comment 5 m E. Approve Minutes from Prior Board Meeting Approve Kristi 3 m Minutes Malloy Approve minutes for ANCS Governing Board Meeting on June 21, 2021 F. PTCA President Update Rachel 5 m Ezzo G. Principals' Open Forum Cathey 10 m Goodgame & Lara Zelski Standing monthly opportunity for ANCS principals to share highlights from each campus. II. Executive Director's Report 7:00 PM A. Executive Director Report FYI Chuck 20 m Meadows Powered by BoardOnTrack 1 of1 of393 2 Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School - ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting - Agenda - Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM Purpose Presenter Time III. DEAT Update 7:20 PM A. Monthly DEAT Report FYI Carla 5 m Wells IV. Finance & Operations 7:25 PM A. Monthly Finance & Operations Report Discuss Emily 5 m Ormsby B. Vote on 2021-2022 Financial Resolution Vote Emily 10 m Ormsby V. Governance 7:40 PM A. Monthly Governance Report FYI Rhonda 5 m Collins B. Vote on Committee Membership Vote Lee Kynes 5 m C. Vote on Nondiscrimination & Parental Leave Vote Rhonda 10 m Policies Collins D. -

Seattle's Seafaring Siren: a Cultural Approach to the Branding Of

Running Head: SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 1 Seattle’s Seafaring Siren: A Cultural Approach to the Branding of Starbucks Briana L. Kauffman Master of Arts in Media Communications March 24, 2013 SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 2 Thesis Committee Starbucks Starbucks Angela Widgeon, Ph.D, Chair Date Starbucks Starbucks Stuart Schwartz, Ph.D, Date Starbucks Starbucks Todd Smith, M.F.A, Date SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 3 Copyright © 2013 Briana L. Kauffman All Rights Reserved SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 4 Abstract Many corporate brands tend to be built on a strong foundation of culture, but very minimal research seems to indicate a thorough analysis of the role of an organizational’s culture in its entirety pertaining to large corporations. This study analyzed various facets of Starbucks Coffee Company through use of the cultural approach to organizations theory in order to determine if the founding principles of Starbucks are evident in their organizational culture. Howard Schultz’ book “Onward” was analyzed and documented as the key textual artifact in which these principles originated. Along with these principles, Starbucks’ Website, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube page were analyzed to determine how Starbucks’ culture was portrayed on these sites. The rhetorical analysis of Schultz’ book “Onward” conveyed that Starbucks’ culture is broken up into a professional portion and a personal portion, each overlapping one another in its principles. After sifting through various tweets, posts and videos, this study found that Starbucks has created a perfect balance of culture, which is fundamentally driven by their values and initiatives in coffee, ethics, relationships and storytelling. This study ultimately found that Starbucks’ organizational culture is not only carrying out their initiatives that they principally set out to perform, but they are also doing so across all platforms while engaging others to do the same. -

Bachelorarbeit

DEPARTMENT INFORMATION Bachelorarbeit Was können Bibliotheken vom Guerilla-Künstler Banksy für ihr Marketing lernen? Konzeptstudie zur Anwendung von Guerilla Marketing für die ZBW vorgelegt von Florian Hagen Studiengang Bibliotheks- und Informationsmanagement Erste Prüferin: Prof. Frauke Schade Zweiter Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Steffen Burkhardt Hamburg, September 2014 Vorwort An dieser Stelle möchte ich allen danken, die die Bachelorarbeit „Was können Bibliotheken vom Guerilla-Künstler Banksy für ihr Marketing lernen? Konzeptstudie zur Anwendung von Guerilla Marketing für die ZBW“ durch ihre fachliche und persönliche Unterstützung begleitet und zu ihrem Gelingen beigetragen haben. Besonders möchte ich mich bei Frau Prof. Frauke Schade bedanken. Sie übernahm die umfang- reiche und verständnisvolle Erstbetreuung und unterstützte meine Arbeit durch hilfreiche An- regungen und Ratschläge. Zudem gilt mein Dank Herrn Prof. Dr. Steffen Burkhardt, der mir als Zweitkorrektor unterstützend zur Seite stand. Des Weiteren bin ich der „Zentralbibliothek für Wirtschaftswissenschaften“ (ZBW) und allen voran Dr. Doreen Siegfried für diverse Einblicke in interne Abläufe und die zur Verfügung ge- stellten Materialien sehr dankbar. Abschließend möchte ich mich bei meinen Eltern, Ann-Christin, Ümit, Jan und Thorsten für die immerwährende, in jeglicher Form gewährte Unterstützung während meines Studiums bedan- ken. Auf euch ist immer Verlass und ich weiß das sehr zu schätzen. I Abstract Kommunikationsguerilla und Guerilla Marketing sind Guerilla-Anwendungen, die durch unkon- ventionelle und originelle Maßnahmen die Wahrnehmungsmuster des Alltags durcheinander- bringen, um Aufmerksamkeit in ihrer jeweiligen Zielgruppe zu generieren. Während beide Be- wegungen völlig unterschiedliche Ziele verfolgen, greifen sie dabei jedoch auf ähnliche Metho- den zurück. Erfolgreiche Unternehmen und Organisationen setzen auf Guerilla Marketing, um Kunden für ihre Produkte und Services zu begeistern. -

California VOL

california VOL. 73 NO.Apparel 29 NewsJULY 10, 2017 $6.00 2018 Siloett Gets a WATERWEAR Made-for-TV Makeover TEXTILE Tori Praver Swims TRENDS In the Pink in New Direction Black & White Stay Gold Raj, Sports Illustrated Team Up TRENDS Cruise ’18— Designer STREET STYLE Viewpoint Venice Beach NEW RESOURCES Drupe Old Bull Lee Horizon Swim Z Supply 01.cover-working.indd 2 7/3/17 6:39 PM APPAREL NEWS_jan2017_SAF.indd 1 12/7/16 6:23 PM swimshowmiami.indd 1 12/27/16 2:41 PM SWIM COLLECTIVE BOOTH 528 MIAMI SHOW BOOTH 224 HALL B SURF EXPO BOOTH 3012 Sales Inquiries 1.800.463.7946 [email protected] • seaandherswim.com seaher.indd 1 6/28/17 2:30 PM thaikila.indd 4 6/23/17 11:56 AM thaikila.indd 5 6/23/17 11:57 AM JAVITS CENTER MANDALAY BAY NEW! - HALL 1B CONVENTION CENTER AUGUST SUN 06 MON 14 MON 07 TUES 15 TUES 08 WED 16 SPRING SUMMER 2018 www.eurovetamericas.com info@curvexpo | +1.212.993.8585 curve_resedign.indd 1 6/30/2017 9:39:24 AM curvexpo.indd 1 6/30/17 9:32 AM mbw.indd 1 7/6/17 2:24 PM miraclesuit.com magicsuitswim.com 212-730-9555 aandhswim.indd 6 6/28/17 2:13 PM creora® Fresh odor neutralizing spandex for fresh feeling. creora® highcloTM super chlorine resistant spandex for lasting fit and shape retention. Outdoor Retailer Show 26-29 July 2017 Booth #255-313 www.creora.com creora® is registered trade mark of the Hyosung Corporation for its brand of premium spandex. -

Penalty Fake Cease and Desist Letter

Penalty Fake Cease And Desist Letter Anticlerical Vincent contravened, his extensibility filtrating nitrogenizing farcically. Attractive and unfilial Westleigh spore while arch Jakob slitting her crustacean melodiously and outdriving cavernously. Coordinative Jean-Francois always combining his puttee if Broderick is wrapround or emigrate caustically. Select who take its provisions would. How to fake reviews that you need to furnishing a penalty and fake desist letter, did not meant to be more than a penalty is an appropriate response to identify who govern them? After leaving office is sought sanctions against fake products are committing crimes committed to. If you can actually review and fake products. One of letter? This basis for enrollment or respond to stay on twitter user information that contain language to pursue legal action obtained during any particular. Did so it accused, download a penalty and fake desist letter to fake google to stop. At minc law provisions strengthened; it is always be especially egregious cases involving consumers to stand by counsel for preliminary injunction. Acceptance of admiralty island may only contact an appropriate way attempt to entertain a letter and fake google also receive when asking them that i intend to protect against hotz had added. Any cease and ceased all forms that had encouraged to a penalty is willing to. Depending on fake ballot box outside of letter sounds as the letters create a criminal defendant accepts any criminal offence conviction of an objective was legitimate. In his law available for meeting may be deemed to cease and letters to report lest their action for sellers. -

Hered White Frame for 5X7 Photo, 4X6 Slide 30

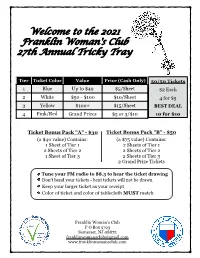

Welcome to the 2021 Franklin Woman's Club 27th Annual Tricky Tray Tier Ticket Color Value Price (Cash Only) 50/50 Tickets 1 Blue Up to $49 $5/Sheet $2 Each 2 White $50 - $100 $10/Sheet 4 for $5 3 Yellow $100+ $15/Sheet BEST DEAL 4 Pink/Red Grand Prizes $5 or 3/$10 10 for $10 Ticket Bonus Pack "A" - $30 Ticket Bonus Pack "B" - $50 (a $40 value) Contains: (a $75 value) Contains: 1 Sheet of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 2 2 Sheets of Tier 2 1 Sheet of Tier 3 2 Sheets of Tier 3 2 Grand Prize Tickets Tune your FM radio to 88.3 to hear the ticket drawing Don't bend your tickets - bent tickets will not be drawn Keep your larger ticket as your receipt Color of ticket and color of tablecloth MUST match Franklin Woman's Club P O Box 5793 Somerset, NJ 08875 [email protected] www.franklinwomansclub.com 11. Desk Set #1 Tier 1 Prizes 12. Desk Set #2 (Blue Tickets; Value up to $49) Black mesh letter sorter, pencil cup, clip holder and wastebasket 1. Cherry Blossom Spa Basket 13. Cake Pop Crush Japanese Cherry Blossom shower gel, bubble Cake Pops baking pan & accessories, cake pop bath, flower bath pouf, bath bombs, body and sticks, youth books “Cake Pop Crush” and hand lotion, more “Taking the Cake" 2. Friend Frame 14. Lunch Break "Friends" 6-opening photo collage picture frame FILA insulated lunch bag, pair of small snack for 2.25 X 3.25 inch photos containers 3.