Survey of Elephants in the Mannar District, Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Features and Fisheries Potential of Palk Bay, Palk Strait and Its Environs

J. Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2005 33(4): 225-232 FEATURE ARTICLE GENERAL FEATURES AND FISHERIES POTENTIAL OF PALK BAY, PALK STRAIT AND ITS ENVIRONS S. SIVALINGAM* 18, Pamankade Lane, Colombo 6. Abstract: The issue of possible social and environmental serving in the former Department of Fisheries, impacts of the shipping canal proposed for the Palk Bay and Colombo (now Ministry of Fisheries and Aquatic Palk Strait area is a much debated topic. Therefore it is Resources) and also recently when consultation necessary to explore the general features of the said area to assess such impacts when formulating the development and assignments were done in these areas. Other management programmes relevant to the area. This paper available data have also been brought together discussed the general features of the area, its environmental and a comprehensive picture of the general and ecological condition and the fisheries potential in detail features and fisheries potential of the areas so as to give some insight to the reader on this important under study is presented below. topic. This article is based on the data collected from earlier field visits and other published information relevant to the subject. GENERAL FEATURES INTRODUCTION Palk Bay and Palk Strait together (also called Sethusamudram), consist of an area of about Considerable interest has been created in the 17,000km2. This is an almost enclosed shallow water Palk Bay, Palk Strait and its environs recently as body that separates Sri Lanka from the a result of the Indian project to construct a mainland India and opens on the east into the shipping canal to connect Gulf of Mannar BOB ( Figure 1 ). -

Sri Lanka's North Ii: Rebuilding Under the Military

SRI LANKA’S NORTH II: REBUILDING UNDER THE MILITARY Asia Report N°220 – 16 March 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. LIMITED PROGRESS, DANGEROUS TRENDS ........................................................ 2 A. RECONSTRUCTION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ..................................................................... 3 B. RESETTLEMENT: DIFFICULT LIVES FOR RETURNEES .................................................................... 4 1. Funding shortage .......................................................................................................................... 6 2. Housing shortage ......................................................................................................................... 7 3. Lack of jobs, livelihoods and economic opportunities ................................................................. 8 4. Poverty and food insecurity ....................................................................................................... 10 5. Lack of psychological support and trauma counselling ............................................................. 11 6. The PTF and limitations on the work of humanitarian agencies .............................................. 12 III. LAND, RESOURCES AND THE MILITARISATION OF NORTHERN DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................................... -

Newsletter Supporting Communities in Need

NEWSLETTER ICRC JULY-SEPTEMBER 2014 SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES IN NEED Economic security and water and sanitation for the vulnerable Dear Reader, they could reduce the immense economic This year, the ICRC started a Community Conflicts destroy livelihoods and hardships and poverty under which they Based Livelihood Support Programme infrastructure which provide water and and their families are living at present” (para (CBLSP) to support vulnerable communities sanitation to communities. Throughout 5.112). in the Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi districts the world, the ICRC strives to enable access to establish or consolidate an income to clean water and sanitation and ensure The ICRC’s response during the recovery generating activity. economic security for people affected by phase to those made vulnerable by the conflict so they can either restore or start a conflict was the piloting of a Micro Economic The ICRC’s economic security programmes livelihood. Initiatives (MEI) programme for women- are closely linked to its water and sanitation headed households, people with disabilities initiatives. In Sri Lanka today, the ICRC supports and extremely vulnerable households in vulnerable households and communities In Sri Lanka, the ICRC restores wells the Vavuniya district in 2011. The MEI is in the former conflict areas to become contaminated as a result of monsoonal a programme in which each beneficiary economically independent through flooding, and renovates and builds pipe identifies and designs the livelihood sustainable income generation activities and networks, overhead water tanks, and for which he or she needs assistance to provides them clean water and sanitation by toilets in rural communities for returnee implement, thereby employing a bottom- cleaning wells and repairing or constructing populations to have access to clean water up needs-based approach. -

Statistical Information 2009

Northern Provincial Council Statistical Information 2009 Figur e 11.7 Disabled Per sons in NP - 2002 - 2007 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 Year 0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Provincial Planning Secretariat, Northern Province Varothayanagar, Trincomalee. TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES PAGE 1.1 LAND AREA OF NORTHERN PROVINCE BY DISTRICT ................................................................................ 01 1.2 DIVISIONAL SECRETARY'S DIVISIONS, MULLAITIVU DISTRICT ............................................................. 03 1.3 DIVISIONAL SECRETARY'S DIVISIONS, KILINOCHCHI DISTRICT ............................................................ 03 1.4.1 GN DIVISION IN DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION – MULLAITIVU DISTRICT.............................. 05 1.4.2 GN DIVISION IN DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION – MULLAITIVU DISTRICT.............................. 06 1.5.1 GN DIVISION IN DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION – KILINOCHCHI DISTRICT............................. 07 1.5.2 GN DIVISION IN DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION – KILINOCHCHI DISTRICT............................. 08 1.6 DIVISIONAL SECRETARY'S DIVISIONS, VAVUNIYA DISTRICT................................................................. 09 1.7 DIVISIONAL SECRETARY'S DIVISIONS, MANNAR DISTRICT..................................................................... 09 1.8.1 GN DIVISION IN DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION – VAVUNIYA DISTRICT ................................. 11 1.8.2 GN DIVISION IN DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION – VAVUNIYA DISTRICT ................................ -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Abuses in Recruitment Practices at the University of Jaffna

DISCRIMINATING AGAINST EXCELLENCE: ABUSES IN RECRUITMENT PRACTICES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF JAFFNA SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS • The Subcommittee for Academic Integrity of the Jaffna University Science Teachers’ Association found blatant, endemic abuse across several university departments and units in the selection of academic and non-academic staff. The root of this abuse is both political and personal patronage which operates at all levels of the system, and an unwillingness of senior professors and the administration to challenge it, and of the UGC to fulfil its responsibilities in the selection of able and independent Council members and in the regulation of the administration of universities • The most prevalent form of abuse documented is in the selection of probationary lecturers (or assistant lecturers), resulting in the most highly qualified candidates such as First Class degree-holders being systematically excluded from consideration or denied positions. • We also found evidence of systematic abuse and political manipulation for non-academic staff appointments for Computer Applications Assistants (CAA) and Labourers. Favours were given to labourer candidates that were denied to highly qualified lecturers whose services the university badly needs. We recommend: 1. That all cases where complaints have been filed be reviewed swiftly and highly qualified applicants that were excluded at interviews be called. To guard against retaliation, applicants who have filed complaints should have their cases heard by a special review board appointed in consultation with the Unions. 2. That independent persons of repute with an appreciation of university values should be appointed to the Council as external members, and student representatives and academic staff must be allowed to review their qualifications. -

Characterization of Irrigation Water Quality of Chunnakam Aquifer in Jaffna Peninsula

Tropical Agricultural Research Vol. 23 (3): 237 – 248 (2012) Characterization of Irrigation Water Quality of Chunnakam Aquifer in Jaffna Peninsula A. Sutharsiny, S. Pathmarajah1*, M. Thushyanthy2 and V. Meththika3 Postgraduate Institute of Agriculture University of Peradeniya Sri Lanka ABSTRACT. Chunnakam aquifer is the main lime stone aquifer of Jaffna Peninsula. This study focused on characterization of Chunnakam aquifer for its suitability for irrigation. Groundwater samples were collected from wells to represent different uses such as domestic, domestic with home garden, public wells and farm wells during January to April 2011. Important chemical parameters, namely electrical conductivity (EC), chloride, calcium, magnesium, carbonate, bicarbonate, sulfate, sodium and potassium were determined in water samples from 44 wells. Sodium percentage, Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), and residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) levels were calculated using standard equations to map the spatial variation of irrigation water quality of the aquifer using GIS. Groundwater was classified based on Chadha diagram and US salinity diagram. Two major hydro chemical facies Ca-Mg-Cl-SO4 and Na-Cl-SO4 were identified using Chadha diagram. Accordingly, it indicates permanent hardness and salinity problems. Based on EC, 16 % of the monitored wells showed good quality and 16 % showed unsuitable water for irrigation. Based on sodium percentage, 7 % has excellent and 23 % has doubtful irrigation water quality. However, according to SAR and RSC values, most of the wells have water good for irrigation. US salinity hazard diagram showed, 16 % as medium salinity and low alkali hazard. These groundwater sources can be used to irrigate all types of soils with little danger of increasing exchangeable sodium in soil. -

Environmental Assessment Report Sri Lanka

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination – Provincial Roads Component: Mannar–Vavuniya District Project Number: 42254 May 2010 Sri Lanka: Northern Road Connectivity Project Prepared by [Author(s)] [Firm] [City, Country] Prepared by the Ministry of Local Govern ment and Provincial Councils for th e Asian Development Bank (ADB). Prepared for [Executing Agency] [Implementi ng Agency] The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of AD B’s Board of Di rectors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s in nature. members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank BIQ - Basic Information Questionnaire CCD - Coast Conservation Department CEA - Central Environmental Authority CEB - Ceylon Electricity Board CSC - Consultant Supervision Consultant DBST - Double Bituminous Surface Treatment DCS - Department of Census and Statistics DoF - Department of Forestry DoI - Department of Irrigation DoS - Department of Survey DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division DWLC - Department of Wild Life Conservation EA - Executive Agency EMP - Environmental Management Plan EMo - Environmental Monitoring Plan EPL - Environment Protection Liaison ESCM - Environmental Safeguards Compliance Manual GND - Grama Niladhari Division GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GSMB - Geological -

The Government of the Democratic

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 DEPARTMENT OF STATE ACCOUNTS GENERAL TREASURY COLOMBO-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. Note to Readers 1 2. Statement of Responsibility 2 3. Statement of Financial Performance for the Year ended 31st December 2019 3 4. Statement of Financial Position as at 31st December 2019 4 5. Statement of Cash Flow for the Year ended 31st December 2019 5 6. Statement of Changes in Net Assets / Equity for the Year ended 31st December 2019 6 7. Current Year Actual vs Budget 7 8. Significant Accounting Policies 8-12 9. Time of Recording and Measurement for Presenting the Financial Statements of Republic 13-14 Notes 10. Note 1-10 - Notes to the Financial Statements 15-19 11. Note 11 - Foreign Borrowings 20-26 12. Note 12 - Foreign Grants 27-28 13. Note 13 - Domestic Non-Bank Borrowings 29 14. Note 14 - Domestic Debt Repayment 29 15. Note 15 - Recoveries from On-Lending 29 16. Note 16 - Statement of Non-Financial Assets 30-37 17. Note 17 - Advances to Public Officers 38 18. Note 18 - Advances to Government Departments 38 19. Note 19 - Membership Fees Paid 38 20. Note 20 - On-Lending 39-40 21. Note 21 (Note 21.1-21.5) - Capital Contribution/Shareholding in the Commercial Public Corporations/State Owned Companies/Plantation Companies/ Development Bank (8568/8548) 41-46 22. Note 22 - Rent and Work Advance Account 47-51 23. Note 23 - Consolidated Fund 52 24. Note 24 - Foreign Loan Revolving Funds 52 25. -

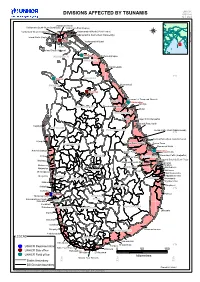

DIVISIONS AFFECTED by TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka

UNHCR DIVISIONS AFFECTED BY TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka ValikamamValikamam NorthNorth ValikamamValikamam South-WestSouth-West (Sandilipay)(Sandilipay) ValikamamValikamam EastEast (Kopay)(Kopay) Valikamam West (Chankanai) VadamaradchiVadamaradchi NorthNorth (Point(Point Perdro)Perdro) JAFFNAJAFFNA VadamaradchiVadamaradchi South-WestSouth-West (Karaveddy)(Karaveddy) Island North (Kayts) JaffnaJaffna VadamaradchiVadamaradchi EastEast Divisions.WOR Affected Jaffna DelftDelft DelftDelftIsland South (Velanai) KillinochchiKillinochchi KILINOCHCHIKILINOCHCHI KillinochchiKillinochchi PuthukudiyiruppuPuthukudiyiruppu MULLAITIVUMULLAITIVU MaritimepattuMaritimepattu 9°N MannarMannar VAVUNIYAVAVUNIYA MANNARMANNAR KuchchaveliKuchchaveli VavuniyaVavuniya TrincomaleeTrincomalee TownTown andand GravetsGravets MorawewaMorawewa TrincomaleeTrincomalee KinniyaKinniya ANURADHAPURAANURADHAPURA ThambalagamuwaThambalagamuwa MutturMuttur TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE SeruvilaSeruvila Verugal/Verugal/ EchchilampattaiEchchilampattai KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu NorthNorth KalpitiyaKalpitiya PUTTALAMPUTTALAM POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Oddamavadi)(Oddamavadi) 8°N KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Valachchenai)(Valachchenai) MundelMundel KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown KURUNEGALAKURUNEGALA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown ManmunaiManmunai NorthNorth ArachchikattuwaArachchikattuwa BatticaloaBatticaloa EravurEravur PattuPattu BatticaloaBatticaloaKattankudyKattankudy ManmunaiManmunai -

Country of Origin Information Report Sri Lanka May 2007

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 11 MAY 2007 Border & Immigration Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 11 MAY 2007 SRI LANKA Contents PREFACE Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA, FROM 1 APRIL 2007 TO 30 APRIL 2007 REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 AND 30 APRIL 2007 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY........................................................................................ 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY............................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY.............................................................................................. 3.01 The Internal conflict and the peace process.............................. 3.13 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS...................................................................... 4.01 Useful sources.............................................................................. 4.21 5. CONSTITUTION..................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .............................................................................. 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 7.01 8. SECURITY FORCES............................................................................... 8.01 Police............................................................................................ -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum