The Voyage Author(S): Jonas Lied Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developments in Arctic Shipping and Logistics

Felix H. Tschudi Tschudi Shipping Company Centre for High North Logistics Developments in Arctic Shipping and Logistics Seminar on Economic Risks and Opportunities in the Arctic Reykjavik, 22.11.2012 TSCHUDI SHIPPING COMPANY The Tschudi Group with roots back to 1883 (www.tschudishipping.com) is an offshore, shipping and logistics group with particular focus on the east-west trades of cargoes and projects involving the Baltic, Russia and the CIS countries including the High North of Russia and Norway. CONVENTIONAL SHIPPING ICE CLASS MULTIPURPOSE CONTAINER VESSELS TANKERS, BULK AND COMBINATION CARRIERS PROJECT CARGOES COMMODITY SHIPPING OFFSHORE •Anchorhandling tug supply vessels •Ocean going tugs TSCHUDI LOGISTICS East – West .Container lines logistics between western Europe, .Door – door transportation Russia and the Central Asian .Project cargoes Republic .Rail and road forwarding Including Tschudi Northern Logistics based in Kirkenes and Murmansk, specialising in cross border transportation and custom clearance The TSC rationale for focusing on logistics in the High North is: . Energy and Mineral Resource development in the High North is accelerating transport solutions are key to its realisation! . This development is possible due to : climate change - ice reduction technological developments - resource extraction/ice operations active interest from Russia and a general cooperative spirit but most importantly; high commodity prices Sydvaranger Gruve – Northern Iron In 2006, the closed down Sydvaranger iron ore mine in Kirkenes, Northern Norway was acquired in order to gain access to arctic port facilities. In November 2009 the first vessel was loaded for China with 75 000 of iron ore concentrate. During 2010 all shipments went to China The company Northern Iron (www.northerniron.com.au) is listed on the Australian stock exchange (ASX) Tschudi controls 20% of the outstanding shares today. -

Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R

STUDIA FORESTALIA SUECICA NR 39 1966 Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R. An Analysis of Soviet Competitive Potentialities Skogsekonomi i Sovjet~rnionen rned en unalys av landets potentiella konkurrenskraft by KARL VIICTOR ALGTTERE SICOGSH~GSICOLAN ROYAL COLLEGE OF FORESTRY STOCKHOLM Lord Keynes on the role of the economist: "He must study the present in the light of the past for the purpose of the future." Printed in Sweden by ESSELTE AB STOCKHOLM Foreword Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R. is a special study of the forestry sector of the Soviet economy. As such it makes a further contribution to the studies undertaken in recent years to elucidate the means and ends in Soviet planning; also it attempts to assess the competitive potentialities of the U.S.S.R. in international trade. Soviet studies now command a very great interest and are being undertaken at some twenty universities and research institutes mainly in the United States, the United Kingdoin and the German Federal Republic. However, it would seem that the study of the development of the forestry sector has riot received the detailed attention given to other fields. In any case, there have not been any analytical studies published to date elucidating fully the connection between forestry and the forest industries and the integration of both in the economy as a whole. Studies of specific sections have appeared from time to time, but I have no knowledge of any previous study which gives a complete picture of the Soviet forest economy and which could faci- litate the marketing policies of the western world, being undertaken at any university or college. -

The Northern Sea Route: Turning a Transportation Disadvantage Into an Advantage

Felix H. Tschudi Chairman Tschudi Shipping Company Centre for High North Logistics The Northern Sea Route: Turning a transportation Disadvantage into an Advantage Arctic Tipping Points Tromsø, January 25, 2010 CONVENTIONAL SHIPPING ICE CLASS MULTIPURPOSE CONTAINER VESSELS TANKERS, BULK AND COMBINATION CARRIERS PROJECT CARGOES COMMODITY SHIPPING OFFSHORE •Anchorhandling tug supply vessels •Ocean going tugs Tschudi Logistics .Container lines East – West logistics between .Door – door transportation western Europe, Russia and the . Central Asian Project cargoes Republic .Rail and road forwarding Including Tschudi Northern Logistics based in Kirkenes and Murmansk, specialising in cross border transportation and custom clearance We like to see the Earth from this Direction The TSC rationale for focusing on logistics in the High North is: . Energy and Mineral Resource development in the High North is now accelerating transport solutions are key to realising this . This development is more realistic than ever before due to : ice reduction technological developments high commodity prices and, not least, an interest from Russia in making it possible. Too large savings to be ignored! An example: Iron ore prices and the importance of freight Centre for High North Logistics An international independent non-profit organisation initiated by TSC and supported by the Norwegian MFA , Statoil, DnV and others (www.chnl.no) Vision: To be the preferred knowledge network for creating and developing efficient and sustainable logistical solutions for the -

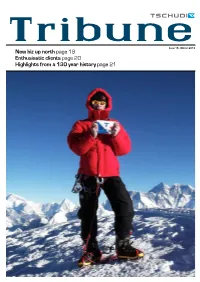

New Biz up North Page 19 Enthusiastic Clients Page 20 Highlights from a 130 Year History Page 21 2 Contents Editorial 3

Issue 15 - Winter 2013 New biz up north page 19 Enthusiastic clients page 20 Highlights from a 130 year history page 21 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 Editorial 3 Networking in Angola 4 Tow out 6 An ocean of opportunities 9 Double green for Tschudi Logistics 10 Good teamwork – the key to success 12 Fridtjof Nansen’s footsteps 14 Strong team working together 17 More gas to Japan 18 New biz up north 19 Enthusiastic clients 20 Highlights from a 130 year history 21 Dear friends News from sea 29 News from Holland 34 and colleagues! News from England 36 News from Finland 37 Welcome to the December 2013 issue of the Tschudi Tribune. lowering our standards is not an issue. Even if the markets News from Russia 38 Our regular readers will hopefully discover that this issue has don’t always reward a good service in monetary terms, we are News from Latvia 39 130 YEARS been subject to a “makeover” and has a “fresher” look than pleased that for our conventional and unconventional shipping Moderne Transport prize 40 previous ones. As this issue of the Tschudi Tribune goes to services we also experience repeat business and good refer- South meets north 42 print Tschudi Shipping Company’s 130th year is coming to an ences. It again shows that performance is all about people and Out and nbout 44 New faces 45 end but it is hoped that this magazine will assist us in com- that we have the right people with the right attitude onboard Where to find your colleagues 46 municating that the Tschudi Group is only 130 years young and ashore. -

Downloaded from the Web-Site

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 52, August, 2006 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089-4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740-2735 Fax: (213) 740-8550; E: [email protected] website: http://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the fifty-second biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in February, 2006. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the spring and summer of 2006. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2005 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can also be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 if overseas airmail). In August, 2004, the IMRC transferred the Newsletter to an electronic format and individuals and institutions on our courtesy list are receiving the issues as an e-attachment. Members in full standing, however, continue to receive hard copies of the Newsletter as well as the text in electronic format, wherever feasible. Please send us new and corrected e-mail addresses. An illustrated brochure describing the programs, collections, and functions of the IMRC is also available RUSSIA: Land of Milk and Money Amidst the astounding material abundance in the new Moscow, symbolized by the colossal twenty- four hour hypermarkets and the mega department stores, there is a line of products which stands quite apart from the Italian footwear, Chinese jeans, Japanese sushi and German lawnmowers – and that is the ever expanding dairy section in the local food store. -

The Following Section on Early History Was Written by Professor William (Bill) Barr, Arctic Historian, the Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary

The following section on early history was written by Professor William (Bill) Barr, Arctic Historian, The Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary. Prof. Barr has published numerous books and articles on the history of exploration of the Arctic. In 2006, William Barr received a Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to the recorded history of the Canadian North from the Canadian Historical Association. As well, Prof. Barr, a known admirer of Russian Arctic explorers, has been credited with making known to the wider public the exploits of Polar explorations by Russia and the Soviet Union. HISTORY OF ARCTIC SHIPPING UP UNTIL 1945 Northwest Passage The history of the search for a navigable Northwest Passage by ships of European nations is an extremely long one, starting as early as 1497. Initially the aim of the British and Dutch was to find a route to the Orient to grab their share of the lucrative trade with India, Southeast Asia and China, till then monopolized by Spain and Portugal which controlled the route via the Cape of Good Hope. In 1497 John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto), sponsored by King Henry VII of England, sailed from Bristol in Mathew; he made a landfall variously identified as on the coast of Newfoundland or of Cape Breton, but came no closer to finding the Passage (Williamson 1962). Over the following decade or so, he was followed (unsuccessfully) by the Portuguese seafarers Gaspar Corte Real and his brother Miguel, and also by John Cabot’s brother Sebastian, who some theorize, penetrated Hudson Strait (Hoffman 1961). The first expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage that are definitely known to have reached the Arctic were those of the English captain, Martin Frobisher in 1576, 1577 and 1578 (Collinson 1867; Stefansson 1938). -

The Historical and Cultural Heritage of Russia Историческое И Культурное Наследие России

Министерство образования и науки Российской Федерации Сибирский федеральный университет Е.В. СЕМЕНОВА, В.И. СЕМЕНОВ, Л.Э. ТОМАС THE HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE OF RUSSIA ИСТОРИЧЕСКОЕ И КУЛЬТУРНОЕ НАСЛЕДИЕ РОССИИ Рекомендовано: УМО РАЕ по классическому университетскому и техническому образованию в качестве учебного пособия для студентов высшего профессионального образования, обучающихся по направлению подготовки 050100.62 – «Педагогическое образование» (Профиль подготовки: 050100.62.00.12 – «Иностранный язык»)» (Протоко л № 514 от 25 мая 2015 г.) Издание второе, дополненное Красноярск, Лесосибирск 2016 УДК 37 (930.85) ББК 81.2 С 30 Рецензенты: В.И. Петрищев, доктор педагогических наук, профессор, академик Академии социальных наук; Л.Н. Перевалова, учитель английского языка высшей категории, МБОУ «Гимназия», г. Лесосибирск Семенова Е.В., Семенов В.И., Томас Л.Э. С 30 Историческое и культурное наследие России: учеб. пособие, англ. / Е.В. Семенова, В.И. Семенов, Л.Э. Томас. 2-е изд., доп. Красноярск: Сибирский федеральный ун-т, 2016. 147 с. ISBN 978-57638-3443-7 Пособие содержит материалы, тексты, задания на английском языке по истории и культуре России для студентов педагогических вузов – будущих учителей иностранного языка. Пособие знакомит с историей и культурой России на примере Москвы, Санкт-Петербурга, Красноярска, города-памятника Енисейска и молодого сибирского города Лесосибирска. Приводится вокабуляр по основным темам курса. В приложении представлены задания и извлечения из специальной литературы, которые помогут студентам лучше усвоить материал пособия. Для студентов и преподавателей гуманитарных вузов, направление «педагогическое образование», профиль «иностранный язык», для учителей английского языка, а также для широкого круга лиц, изучающих английский язык. УДК 37 (930.85) ББК 81.2 ISBN 978-57638-3288-4 ( 1-е изд.) ISBN 978-57638- 3443-7 (2-е изд.) © ЛПИ – филиал СФУ, 2016 © Е.В. -

British Perceptions of Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Fedorovna

British Perceptions of Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Fedorovna 1894-1918 Claire Theresa McKee UCL PhD I, Claire Theresa McKee confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: C.T. McKee 1 Abstract Attitudes towards Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Fedorovna can be characterised by extremes, from hostility to sentimentality. A great deal of what has been written about the imperial couple (in modern times) has been based on official records and with reference to the memoirs of people who knew the tsar and empress. This thesis recognises the importance of these sources in understanding British perceptions of Nicholas and Alexandra but it also examines reactions in a wider variety of material; including mass circulation newspapers, literary journals and private correspondence. These sources reveal a number of the strands which helped form British understanding of the tsar and empress. In particular, perceptions were influenced by internal British politics, by class and by attitudes to the role of the British Empire in world affairs, by British propaganda and by a view of Russia and her society which was at times perceptive and at others antiquated. This thesis seeks to evaluate diverse British views of Nicholas and Alexandra and to consider the reasons behind the sympathetic, the critical, the naïve and the knowledgeable perceptions of the last tsar and empress of Russia. 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements p. 4 Preface p.5 Abbreviations p. 6 Introduction: Sources, Personalities and their World p. -

Trading with the Communists: the International Aluminium Industry

12th Annual Conference of the European Business History Association, Bergen, 21-23 August, 2008 The Cartel and the Communists: The Aluminium Industry and the Norwegian Export Guarantees, 1929-1935 Espen Storli, PhD-student, Department of History and Classical Studies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim [email protected] The Soviet Union was one of the few growing markets in the world during the worldwide economic depression after 1929, and to many Western corporations exports to the country appeared to be a potential “eldorado”.1 However, trade with the Communists was difficult. There were serious political obstacles to trade, and since the Soviet Union was constantly pressed for hard currency, all the purchases had to be financed through credit arrangements. The difficulties apart, for those corporations that managed to overcome the pitfalls, the affairs could be very profitable. The Soviet market was for example virtually essential for the survival of German and US machine exports during the depression. 2 This market was also extremely important for the international aluminium industry. In a period when demand for the metal on practically all other markets was shrinking, the Soviet Union started to import large quantities of aluminium annually. Initially the large aluminium producers competed vigorously for the orders, but after the international aluminium cartel had been reorganized in 1931 the cartel members presented a united front towards the Soviet government by coordinating their sales. However, the large producers had to take into consideration both the presence of independent and semi-independent aluminium companies and the unusual nature of the Soviet sales, i.e. -

NIEMI, SEIJA ASTRID: a Pioneer of Nordic Conservation: the Environmental Literacy of A. E. Nordenskiöld (1832-1901)

ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS B 458 Seija A. Niemi A PIONEER OF NORDIC CONSERVATION: THE ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY OF A. E. NORDENSKIÖLD (1832-1901) Seija A. Niemi Painosalama Oy, Turku , Finland 2018 Turku Painosalama Oy, ISBN 978-951-29-7317-0 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-7318-7 (PDF) TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. B osa - tom. 458 | Humaniora | Turku 2018 ISSN 0082-6987 (PRINT) | ISSN 2343-3191 (PDF) A PIONEER OF NORDIC CONSERVATION: THE ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY OF A. E. NORDENSKIÖLD (1832-1901) Seija A. Niemi TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. B osa - tom. 458 | Humaniora | Turku 2018 University of Turku Faculty of Education Department of teacher education Doctoral Programme on Learning, Teaching and Learning Environments Research Supervised by From year 2017 From year 2016 Mika Kallioinen Tuomas Räsänen University of Turku, Finland University of Turku, Finland To year 2017 To year 2016 Professor Timo Myllyntaus Docent Laura Hollsten University of Turku, Finland Åbo Akademi, Finland Reviewed by Professor Mikko Saikku Docent Jukka Nyyssönen University of Helsinki, Finland FUiT Norges arktiske universitet, Tromsø, Norway Opponent Professor Mikko Saikku University of Helsinki, Finland Custos Professor Mika Kallioinen University of Turku, Finland The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. ISBN 978-951-29-7317-0 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-7318-7 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 (PRINT) ISSN 2343-3191 (PDF) Painosalama Oy – Turku, Finland 2018 5 TURUN YLIOPISTO Humanistinen tiedekunta Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Suomen historia NIEMI, SEIJA ASTRID: A Pioneer of Nordic Conservation: The Environmental Literacy of A. -

Download from Warfare to Welfare

Hans Otto Frøland and Mats Ingulstad (eds.) Hans Otto Frøland and Mats Ingulstad (eds.) Ingulstad Mats and Frøland Otto Hans The rapid growth of the aluminium industry during the last hundred years reflects the status of aluminium as the quintessentially modern metal. Given its impact on every facet of modern life, its aptitude for aca- demic analysis is only rivaled by the versatility of the metal in industrial From Warfare to Welfare application. Business-Government Relations in the Aluminium Industry While during the 19th century aluminium was the source of luxury goods for the rich few, during the First World War it was subjected to strate- gic considerations by belligerent states. It had become a warfare metal. It remained a military-strategic metal well into the 1950s, before it regained a position as a metal for civilian consumption, this time for the masses. This book takes a historical approach, informed by an institutionalist per- spective, to elucidate the political economy of the aluminium industry in the twentieth century. It is structured as a series of analyses of the inter- actions between the state and the corporations in different countries. By Welfare to Warfare From looking at business-government relationships we can better grasp the linkages between the aluminium industry and the two key features of the history of the twentieth century: The rise of the industrial warfare state and its subsequent replacement by the welfare state. The ROSTRA series takes its name from the Forum Romanum rostrum ROSTRA is published by Akademika Publishing in co-operation with the Department of History and Classical Studies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). -

'Icy Futures': Carving the Northern Sea Route Satya

‘Icy Futures’: Carving the Northern Sea Route Satya Savitzky (BA, MA) This thesis is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted January, 2016 I declare that this thesis is my own work, and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the reward of a higher degree elsewhere. (Total word count: 81516) 1 Abstract The research examines intersections between globalisation and climate change in the (re)emergence of a 'Northern Sea Route' through the Russian Arctic, which some speculate could soon rival or replace the Suez Canal as major global trade artery. The research explores shifts in the contemporary shipping system, a relatively underexplored area of mobilities research, examining the affordances and risks posed to shipping and resource extraction activities by melting Arctic sea-ice, as sections of the maritime Arctic become increasingly integrated into global circuits. The research examines actual and potential developments surrounding the Northern Sea Route (NSR) in the Russian Arctic, examining the ways geopolitics, geoeconomics and geophysical processes collide in the ‘Anthropocene Arctic’. 2 ‘Icy Futures’: Carving the Northern Sea Route Satya Savitzky Contents Preface/Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... 6 Chapter one: introduction........................................................................................................... 7 Globalisation, cargo shipping and climate