The Ration Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coercive Governance and Remote Indigenous Communities: the Failed Promise of the Whole of Government Mantra

COERCIVE GOVERNANCE AND REMOTE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES: THE FAILED PROMISE OF THE WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT MANTRA Greg Marks* I Introduction be repudiated. The question is whether the assimilationist and paternalistic assumptions and premises underlying the Old assimilation policies, long thought put to bed, were Howard Government’s approach still have resonance. To re-awoken in pronouncements of the Howard Coalition the extent that assimilationist assumptions may continue to Government. For example, then Prime Minister John have valency there is the potential for policies and programs Howard observed in May 2007: to fail despite the best of intentions. Such failures are likely to present as failures of governance. I have always held the view that the best way to help the Indigenous people of this nation is to give them the greatest This article canvasses in section II the general policy context possible access to the bounty and good fortune of this in respect of responding to Indigenous disadvantage. The nation and that cannot happen unless they are absorbed into particular situation of remote Indigenous communities, our mainstream.1 so much at the centre of public concern and discussion, is described in section III. Section III notes the strong Conservative commentators continue to unashamedly theme of hostility to remote communities (including a promote an assimilationist, or ‘integrationist’, policy line and particular animus against small decentralised communities such ideas appear to have gained a considerable degree of – often referred to as ‘outstations’) evident in the policy traction.2 Justice Elizabeth Evatt, former member of the UN pronouncements and program settings of the previous Human Rights Committee, responding to such statements, government. -

March 2013 Issue No: 119 in This Issue Club Meetings Apologies Contact Us 1

March 2013 Issue No: 119 In this issue Club Meetings Apologies Contact us 1. Zontaring on 2. IWD o Second Thursday of the o By 12 noon previous [email protected] 3. Tricia – Life Member of Stadium www.zontaperth.org.au Snappers Master Swimming Club month (except January) Monday 4. ZCP Holiday Relief Scheme o 6.15pm for 6.45pm o [email protected] PO Box 237 5. Dr Sue Gordon o St Catherine’s College, Nedlands WA 6909 6. Fiona Crowe – Volunteer Fire UWA Fighter 7. Diary Dates 1. Zontaring on…. Larraine McLean, President Since the Inzert in November 2012 we have lost and achieved a great deal! We have suffered the loss of and saluted the efforts of Marg Giles. We held a wake in her honour at the Pioneers Memorial Garden in Kings Park; sent condolence letters and cards to her family; placed a notice in the West Australian Newspaper and produced a special edition of Inzert to commemorate her efforts. Marg was with us at our Christmas event in December. I sat at the same table as Larraine McLean, Marg and she seemed to be enjoying the fellowship and fun around her. Marg, as President always, participated in the Christmas Bring and Buy which was a huge success. Delicious Christmas fare was supplied by members that was quickly bought by other members, friends and guests. It is consoling that Marg’s last time with us seemed to be such a positive event for her. In January we heard of the death of Hariette Yeckel. -

Contents Collection Summary

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies MS 4721 Jon Altman research collection Part B 1979-2014 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT .................................................................. 3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION ...................................................................................... 3 COLLECTION OVERVIEW ........................................................................................ 4 BIOGRAPHICAL/ADMINISTRATIVE NOTE ............................................................. 9 SERIES DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 9 SERIES 12 RESEARCH MATERIAL 1980-1990 ............................................................. 9 Subseries 1. Coronation Hill .............................................................................. 10 Subseries 2. RAC (Resource Assessment Commission) related ...................... 12 Subseries 3. Century mine ................................................................................ 12 SERIES 13. (NTER) NORTHERN TERRITORY EMERGENCY RESPONSE......................... 13 SERIES 14. RESEARCH MATERIAL 2005-2013 .......................................................... 26 Subseries 1. Magazine boxes ........................................................................... 27 Subseries 2. Subject files -

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: a Case Study of the Granites Mine

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: A Case Study of The Granites Mine Rodger Donald Barnes BSc (Geol, Geog) Hons James Cook University A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Architecture Abstract This thesis addresses the important issue of implementation of agreements between Aboriginal people and mining companies. The primary aim is to contribute to developing a framework for considering implementation of agreements by examining how outcomes vary according to the processes and techniques of implementation. The research explores some of the key factors affecting the outcomes of agreements through a single case study of The Granites Agreement between Newmont Mining Corporation and traditional Aboriginal landowners made under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) 1976. This is a fine-grained longitudinal study of the origins and operation of the mining agreement over a 28-year period from its inception in 1983 to 2011. A study of such depth and scope of a single mining agreement between Aboriginal people and miners has not previously been undertaken. The history of The Granites from the first European contact with Aboriginal people is compiled, which sets the study of the Agreement in the context of the continued adaption by Warlpiri people to European colonisation. The examination of the origins and negotiations of the Agreement demonstrates the way very disparate interests between Aboriginal people, government and the mining company were reconciled. A range of political agendas intersected in the course of making the Agreement which created an extremely complex and challenging environment not only for negotiations but also for managing the Agreement once it was signed. -

Essay: Trapped in the Aboriginal Reality Show

Essay: Trapped in the Aboriginal reality show Author: Marcia Langton ean Baudrillard generated international controversy when he described in his essay ‘War Porn’ the way images from Abu Graib prison in Iraq and other J‘consensual and televisual’ violence were used in the aftermath to September 11, 2001. Strong words – perversity, vileness – sparked in his brief, acute analysis: ‘The worst is that it all becomes a parody of violence, a parody of the war itself, pornography becoming the ultimate form of the abjection of war which is unable to be simply war, to be simply about killing, and instead turns itself into a grotesque infantile reality‐show, in a desperate simulacrum of power. These scenes are the illustration of a power, without aim, without purpose, without a plausible enemy, and in total impunity. It is only capable of inflicting gratuitous humiliation.’ This made me think about the everyday suffering of Aboriginal children and women, the men who assault and abuse them, and the use of this suffering as a kind of visual and intellectual pornography in Australian media and public debates. The very public debate about child abuse is like Baudrillard’s ‘war porn’. It has parodied the horrible suffering of Aboriginal people. The crisis in Aboriginal society is now a public spectacle, played out in a vast ‘reality show’ through the media, parliaments, public service and the Aboriginal world. This obscene and pornographic spectacle shifts attention away from everyday lived crisis that many Aboriginal people endure – or do not, dying as they do at excessive rates. This spectacle is not a new phenomenon in Australian public life, but the debate about ‘Indigenous affairs’ has reached a new crescendo, fuelled by the accelerated and uncensored exposé of the extent of Aboriginal child abuse. -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Ready Programs and the Papulu CLC Director David Ross

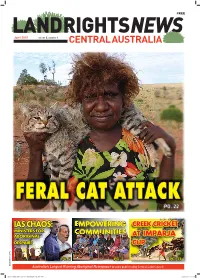

FREE April 2015 VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1. PG. ## FERAL CAT ATTACK PG. 22 IAS CHAOS: EMPOWERING CREEK CRICKET MINISTERS FOR COMMUNITIES ABORIGINAL AT IMPARJA DESPAIR? CUP PG. 2 PG. 2 PG. 33 ISSN 1839-5279 59610 CentralLandCouncil CLC Newspaper 36pp Alts1.indd 1 10/04/2015 12:32 pm NEWS Aboriginal Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion confronts an EDITORIAL angry crowd at the Alice Springs Convention Centre. Land Rights News Central He said organisations got the funding they deserved. Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per year. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Australia Photo courtesy CAAMA To subscribe email: [email protected] IAS chaos sparks ADVERTISING Advertise in the only protests and probe newspaper to reach Aboriginal people THE AUSTRALIAN Senate will inquire original workers. Neighbouring Barkly Regional Council re- into the delayed and chaotic funding round Nearly half of the 33 organisations sur- ported 26 Aboriginal job losses as a result of in remote Central of the new Indigenous advancement scheme veyed by the Alice Springs Chamber of Com- a 35% funding cut to community services in a (IAS), which has done as much for the PM’s merce were offered less funding than they had UHJLRQWURXEOHGE\SHWUROVQLI¿QJ Australia. reputation in Aboriginal Australia as his way previously for ongoing projects. President Barb Shaw told the Tennant with words. -

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No. 116/15cncl TO: ORDINARY COUNCIL – 31 AUGUST 2015 SUBJECT: MAYOR’S REPORT 1. MEETINGS AND APPOINTMENTS 1.1 Robert Sommerville; Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, Mike Crow and Peter Solly 1.2 Alice Springs Masters Games Advisory Committee 1.3 Department of Chief Minister – Scott Lovett 1.4 Rachel and Barb Satour – Rate Payers 1.5 Clontarf - Scott Allen, Greg Buxton & Ian McAdam 1.6 CEOs, Mayors & Presidents Forum, Darwin, The Hon Bess Price, Minister for Local Government and Community Services 1.7 Northern Territory Grants Commission – Peter Thornton 1.8 Post National General Assembly Board Meeting Teleconference 1.9 Deputy Mayor Steve Brown, Cr Brendan Heenan, Cr Eli Melky 1.10 ALGA/Federal Assistance Grants Campaign Steering Committee 1.11 Western Australian Local Government Association Conference, Perth 1.12 Jimmy Cocking ALEC 1.13 Tony Tapsell CEO LGANT 1.14 Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet; Ren Kelly and Trish Johnston Acting Regional Manager 1.15 Tegan Copland - St Phillips College, School assignment 1.16 Hannah Millerick & Chloe Erlich – NT Events Photography 1.17 Alice Springs Accommodation Action Group 1.18 Road Transport Hall of Fame – Meeting re Reunion 2015 1.19 The Hon Robyn Lambley MLA 1.20 Mt Isa to Tennant Creek Pipeline Briefing – Paul Malony, APA Group 1.21 Deputy Mayor Steve Brown, Cr Eli Melky, CEO Rex Mooney 1.22 Debbie Staines - Clarity NT 1.23 Department of Chief Minister, Todd Mall Pop Up Shops 1.24 Athletics’ meeting – Mayor Damien Ryan, Deputy Mayor -

Indigenous Welfare Quarantining in the Northern Territory and Cape York

Balayi: Culture, Law and Colonialism – Volume 10 THE RETURN TO THE LEGAL AND CITIZENSHIP VOID: INDIGENOUS WELFARE QUARANTINING IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY AND CAPE YORK THALIA ANTHONY Introduction This article will suggest that the universal quarantining of Indigenous people‟s social security in Northern Territory communities is a departure from Indigenous people‟s citizenship rights. The Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Payment Reform) Act 2007 (Cth) („Social Security Amendment Act’), which is part of the Commonwealth‟s Northern Territory „emergency‟ measures, represents a return to a historical legal void where Indigenous people had neither rights to their culture nor citizenship rights. The Northern Territory policy, referred to broadly as the „Northern Territory Intervention‟ will be compared to the Commonwealth and State welfare reforms in Cape York, Queensland. Welfare quarantining in Cape York applies to an individual who fails a „responsibility‟ test. It is distinct from the blanket approach to Indigenous welfare recipients in Northern Territory communities. Nonetheless, both systems apply distinctly to Indigenous people and require the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). Both curtail citizenship rights and deny capacities for Indigenous communities to develop their own strategies or economies. In essence, they represent the reemergence of a legal void between Anglo-Australian and Indigenous laws that is filled by paternal state policies. The recurring historical legal void For many years colonial and „post‟(neo)-colonial laws placed Indigenous people in a legal void. Indigenous people were neither allowed to maintain their own Indigenous laws nor to acquire a citizenship status in line with other Australians. -

Department of the Attorney-General and Justice Page 1 of 9

ADULT CHANGE OF NAME BIRTH REGISTERED IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 1. Complete all pages of the form where appropriate and have someone over the age of 18 years witness your signature. If you do not sign your change of name application in front of a witness then it will not be registered. Original application forms must be lodged at a BDM counter or posted in. Please DO NOT FAX or EMAIL in application forms otherwise the change of name will not be processed. 2. Advertise ONCE in any newspaper published and circulating in the Northern Territory. Page Two (2) headed ‘NEWSPAPER ADVERTISEMENT ’ can be used for this purpose. Each applicant needs to organise and pay for the advertisement with the Newspaper. Once the advertisement appears in the Newspaper, remove the FULL PAGE and lodge it together with your completed change of name application form. 3. The reason for the change of name MUST BE PROVIDED . Statements like “Personal”, “I want to”, “Religion” or similar statements are NOT acceptable as reasons for applying to register a change of name. 4. Evidence of identification MUST be sighted prior to a change of name being processed . Please see page Four (4) for full identification requirements. 5. Fees: $88.00 to be paid with lodgement of forms - ($44.00 for the registration fee and $44.00 for a Birth Certificate or Change of Name Certificate). Extra birth or name change certificates are available at a cost of $44.00 each. Registered mail is $12.30 (or $16.10 for international registered mail). Clients can also collect the certificates as per addresses below. -

Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC and SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX D ECONOMIC & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public NOVEMBER 2016 This page has been intentionally left blank Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Public— November 2016 © Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PUBLIC Circle Advisory Pty Ltd PO Box 5428, Albany WA 6332 ACN 161 267 250 ABN 36 161 267 250 T: +61 (0) 419 835 704 F: +61 (0) 9891 6102 E: [email protected] www.circleadvisory.com.au DOCUMENT CONTROL RECORD Document Number NGP_PL002 Project Manager James Kernaghan Author(s) Jane Munday, James Kernaghan, Martin Edwards, Fadzai Matambanadzo, Ben Garwood. Approved by Russell Brooks Approval date 8 November 2016 DOCUMENT HISTORY Version Issue Brief Description Reviewer Approver Date A 12/9/16 Report preparation by authors J Kernaghan B 6/10/16 Authors revision after first review J Kernaghan C 7/11/16 Draft sent to client for review J Kernaghan R Brooks (Jemena) 0 8/11/16 Issued M Rullo R Brooks (Jemena (Jemena) Recipients are responsible for eliminating all superseded documents in their possession. Circle Advisory Pty Ltd. ACN 161 267 250 | ABN 36 161 267 250 Address: PO Box 5428, Albany Western Australia 6332 Telephone: +61 (0) 419 835 704 Facsimile: +61 8 9891 6102 Email: [email protected] Web: www.circleadvisory.com.au Circle Advisory Pty Ltd – NGP ESIA Report 1 Preface The authors would like to acknowledge the support of a wide range of people and organisations who contributed as they could to the overall effort in assessing the potential social and economic impacts of the Northern Gas Pipeline. -

Mungo Man Holds Secrets of First Australians

Elimatta asgmwp.net Summer 2017 Aboriginal Support Group – Manly Warringah Pittwater ICN8728 ASG acknowledges the Guringai People, the traditional owners of the lands and the waters of this area MUNGO MAN HOLDS SECRETS OF FIRST AUSTRALIANS ‘Investing in death’ At a time when Europe was The remains of the first known Australian, Mungo largely populated by Neanderthals Man, have begun their return to the Willandra area of New a much more sophisticated ancient South Wales, where they were discovered in 1974. They’ll be accompanied by the remains of around culture existed down under 100 other Aboriginal people who lived in the Willandra landscape during the last ice age. Their modern descendants, the Mutti Mutti, Paakantyi and Ngyampaa people, will receive the ancestral remains, and will ultimately decide their future. But the hope is that scientists will have some access to the returned remains, which still have much to tell us about the lives of early Aboriginal Australians. The MUNGO Discoveries For more than a century, non-indigenous people have collected the skeletal remains of Aboriginal Australians. This understandably created enormous resentment for many Aboriginal people who objected to the desecration of their grave sites. The removal of the remains from the Willandra was quite different, done to prevent the erosion and destruction of fragile human remains but also to make sense of their meaning. In 1967 Mungo Woman’s cremated remains were found buried in a small pit on the shores of Lake Mungo. Careful excavation by scientists from the Australian National University revealed they were the world’s oldest cremation, dated to some 42,000 years ago.