The Northern Territory 'Emergency Response'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2013 Issue No: 119 in This Issue Club Meetings Apologies Contact Us 1

March 2013 Issue No: 119 In this issue Club Meetings Apologies Contact us 1. Zontaring on 2. IWD o Second Thursday of the o By 12 noon previous [email protected] 3. Tricia – Life Member of Stadium www.zontaperth.org.au Snappers Master Swimming Club month (except January) Monday 4. ZCP Holiday Relief Scheme o 6.15pm for 6.45pm o [email protected] PO Box 237 5. Dr Sue Gordon o St Catherine’s College, Nedlands WA 6909 6. Fiona Crowe – Volunteer Fire UWA Fighter 7. Diary Dates 1. Zontaring on…. Larraine McLean, President Since the Inzert in November 2012 we have lost and achieved a great deal! We have suffered the loss of and saluted the efforts of Marg Giles. We held a wake in her honour at the Pioneers Memorial Garden in Kings Park; sent condolence letters and cards to her family; placed a notice in the West Australian Newspaper and produced a special edition of Inzert to commemorate her efforts. Marg was with us at our Christmas event in December. I sat at the same table as Larraine McLean, Marg and she seemed to be enjoying the fellowship and fun around her. Marg, as President always, participated in the Christmas Bring and Buy which was a huge success. Delicious Christmas fare was supplied by members that was quickly bought by other members, friends and guests. It is consoling that Marg’s last time with us seemed to be such a positive event for her. In January we heard of the death of Hariette Yeckel. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT Contents AIEF Annual Report 2009 1 Messages from our Patrons 2 2 Chairman’s Overview – Ray Martin AM 4 3 Chief Executive’s Report – Andrew Penfold 6 4 AIEF Scholarship Programme 8 5 AIEF 2009 Partner Schools: Kincoppal – Rose Bay School 12 Presbyterian Ladies’ College, Sydney 14 St Catherine’s School, Waverley 16 St Scholastica’s College, Glebe 18 St Vincent’s College, Potts Point 20 Other Partnerships and Scholarships 22 6 Student Overviews – Current and Past Students at 2009 Partner Schools 24 7 Financial Summary 34 APPENDIX A Governance and People 38 B Contact and Donation Details 40 1 Messages from our Patrons Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir AC CVO Governor of New South Wales Patron-in-Chief It is an honour to be the Patron-in-Chief of the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation and to be able to follow the growth and development of the organisation over the past 12 months in its resolve and drive to create opportunities for a quality education for more Indigenous children across the nation. AIEF is an excellent example of how individuals and corporate organisations can make a difference to the lives of Indigenous children by facilitating access to educational opportunities that would not otherwise be available to them, and to do so in an efficient framework that provides clear, transparent and regular reporting. This initiative also benefits non-Indigenous children in our schools by providing the opportunity for our non-Indigenous students to form bonds of friendship with, and cultural understanding of, their Indigenous classmates. In this way, we are together working towards a brighter future for all Australians and empowering Indigenous children to have real choices in life. -

The Task Cards

HEROES HEROES TASK CARD 1 TASK CARD 2 HERO RECEIVES PURPLE CROSS YOUNG AUSTRALIAN OF THE YEAR The Young Australian of the Year has been awarded since 1979. It Read the story about Sarbi and answer these questions. recognises the outstanding achievement of young Australians aged 16 to 30 and the contributions they have made to our communities. 1. What colour is associated with the Australian Special Forces? YEAR Name of Recipient Field of Achievement 2011 Jessica Watson 2. What breed of dog is Sarbi? 2010 Trooper Mark Donaldson VC 2009 Jonty Bush 3. What is Sarbi trained to do? 2008 Casey Stoner 2007 Tania Major 4. What type of animal has also received 2006 Trisha Broadbridge the Purple Cross for wartime service? 2005 Khoa Do 2004 Hugh Evans 5. In which country was Sarbi working 2003 Lleyton Hewitt when she went missing? 2002 Scott Hocknull 2001 James Fitzpatrick 6. How was Sarbi identified when she was found? 2000 Ian Thorpe OAM 1999 Dr Bryan Gaensler 7. What does MIA stand for? 1998 Tan Le 1997 Nova Peris OAM 8. Which word in the text means ‘to attack by surprise’? 1996 Rebecca Chambers 1995 Poppy King 9. How many days was Sarbi missing for? Find out what each of these people received their Young Australian 10. Why did Sarbi receive the Purple cross? Award for. Use this list of achievements to help you. Concert pianist; Astronomer; Champion Tennis Player; Sailor; Palaeontologist; MotoGP World Champion; Business Woman; World Champion Swimmer; Youth Leader & Tsunami Survivor; Anti-poverty Campaigner; Olympic Gold Medallist Athlete; Victim -

Essay: Trapped in the Aboriginal Reality Show

Essay: Trapped in the Aboriginal reality show Author: Marcia Langton ean Baudrillard generated international controversy when he described in his essay ‘War Porn’ the way images from Abu Graib prison in Iraq and other J‘consensual and televisual’ violence were used in the aftermath to September 11, 2001. Strong words – perversity, vileness – sparked in his brief, acute analysis: ‘The worst is that it all becomes a parody of violence, a parody of the war itself, pornography becoming the ultimate form of the abjection of war which is unable to be simply war, to be simply about killing, and instead turns itself into a grotesque infantile reality‐show, in a desperate simulacrum of power. These scenes are the illustration of a power, without aim, without purpose, without a plausible enemy, and in total impunity. It is only capable of inflicting gratuitous humiliation.’ This made me think about the everyday suffering of Aboriginal children and women, the men who assault and abuse them, and the use of this suffering as a kind of visual and intellectual pornography in Australian media and public debates. The very public debate about child abuse is like Baudrillard’s ‘war porn’. It has parodied the horrible suffering of Aboriginal people. The crisis in Aboriginal society is now a public spectacle, played out in a vast ‘reality show’ through the media, parliaments, public service and the Aboriginal world. This obscene and pornographic spectacle shifts attention away from everyday lived crisis that many Aboriginal people endure – or do not, dying as they do at excessive rates. This spectacle is not a new phenomenon in Australian public life, but the debate about ‘Indigenous affairs’ has reached a new crescendo, fuelled by the accelerated and uncensored exposé of the extent of Aboriginal child abuse. -

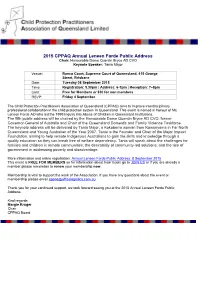

2015 CPPAQ Annual Leneen Forde Public Address Chair: Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO Keynote Speaker: Tania Major

2015 CPPAQ Annual Leneen Forde Public Address Chair: Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO Keynote Speaker: Tania Major Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, 415 George Street, Brisbane Date: Tuesday 08 September 2015 Time: Registration: 5.30pm | Address: 6-7pm | Reception: 7–8pm Cost: Free for Members or $30 for non members RSVP: Friday 4 September The Child Protection Practitioners Association of Queensland (CPPAQ) aims to improve interdisciplinary professional collaboration in the child protection system in Queensland. This event is named in honour of Ms Leneen Forde AO who led the 1999 Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions. The fifth public address will be chaired by the Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO, former Governor-General of Australia and Chair of the Queensland Domestic and Family Violence Taskforce. The keynote address will be delivered by Tania Major, a Kokoberra woman from Kowanyama in Far North Queensland and Young Australian of the Year 2007. Tania is the Founder and Chair of the Major Impact Foundation, aiming to help remote Indigenous Australians to gain the skills and knowledge through a quality education so they can break free of welfare dependency. Tania will speak about the challenges for families and children in remote communities; the desirability of community-led solutions; and the role of government in addressing poverty and disadvantage. More information and online registration: Annual Leneen Forde Public Address: 8 September 2015 This event is FREE FOR MEMBERS so for information about how to join go to JOIN US or if you are already a member please remember to renew your membership now. -

Indigenous Welfare Quarantining in the Northern Territory and Cape York

Balayi: Culture, Law and Colonialism – Volume 10 THE RETURN TO THE LEGAL AND CITIZENSHIP VOID: INDIGENOUS WELFARE QUARANTINING IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY AND CAPE YORK THALIA ANTHONY Introduction This article will suggest that the universal quarantining of Indigenous people‟s social security in Northern Territory communities is a departure from Indigenous people‟s citizenship rights. The Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Payment Reform) Act 2007 (Cth) („Social Security Amendment Act’), which is part of the Commonwealth‟s Northern Territory „emergency‟ measures, represents a return to a historical legal void where Indigenous people had neither rights to their culture nor citizenship rights. The Northern Territory policy, referred to broadly as the „Northern Territory Intervention‟ will be compared to the Commonwealth and State welfare reforms in Cape York, Queensland. Welfare quarantining in Cape York applies to an individual who fails a „responsibility‟ test. It is distinct from the blanket approach to Indigenous welfare recipients in Northern Territory communities. Nonetheless, both systems apply distinctly to Indigenous people and require the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). Both curtail citizenship rights and deny capacities for Indigenous communities to develop their own strategies or economies. In essence, they represent the reemergence of a legal void between Anglo-Australian and Indigenous laws that is filled by paternal state policies. The recurring historical legal void For many years colonial and „post‟(neo)-colonial laws placed Indigenous people in a legal void. Indigenous people were neither allowed to maintain their own Indigenous laws nor to acquire a citizenship status in line with other Australians. -

Mungo Man Holds Secrets of First Australians

Elimatta asgmwp.net Summer 2017 Aboriginal Support Group – Manly Warringah Pittwater ICN8728 ASG acknowledges the Guringai People, the traditional owners of the lands and the waters of this area MUNGO MAN HOLDS SECRETS OF FIRST AUSTRALIANS ‘Investing in death’ At a time when Europe was The remains of the first known Australian, Mungo largely populated by Neanderthals Man, have begun their return to the Willandra area of New a much more sophisticated ancient South Wales, where they were discovered in 1974. They’ll be accompanied by the remains of around culture existed down under 100 other Aboriginal people who lived in the Willandra landscape during the last ice age. Their modern descendants, the Mutti Mutti, Paakantyi and Ngyampaa people, will receive the ancestral remains, and will ultimately decide their future. But the hope is that scientists will have some access to the returned remains, which still have much to tell us about the lives of early Aboriginal Australians. The MUNGO Discoveries For more than a century, non-indigenous people have collected the skeletal remains of Aboriginal Australians. This understandably created enormous resentment for many Aboriginal people who objected to the desecration of their grave sites. The removal of the remains from the Willandra was quite different, done to prevent the erosion and destruction of fragile human remains but also to make sense of their meaning. In 1967 Mungo Woman’s cremated remains were found buried in a small pit on the shores of Lake Mungo. Careful excavation by scientists from the Australian National University revealed they were the world’s oldest cremation, dated to some 42,000 years ago. -

Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen and Women / Noah Riseman

IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), Acton, ANU, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women NOAH RISEMAN Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Riseman, Noah, 1982- author. Title: In defence of country : life stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander servicemen and women / Noah Riseman. ISBN: 9781925022780 (paperback) 9781925022803 (ebook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Wars--Veterans. Aboriginal Australian soldiers--Biography. Australia--Armed Forces--Aboriginal Australians. Dewey Number: 355.00899915094 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Biopolitics Meets Terrapolitics: Political Ontologies and Governance in Settler- Colonial Australia

Biopolitics meets Terrapolitics: Political Ontologies and Governance in Settler- Colonial Australia ∗ Morgan Brigg ∗∗ Keywords : Indigenous Affairs, Governance, Biopolitics, Indigenous Australians, Settler-Colonialism, Political Ontology Abstract Crises persist in Australian Indigenous affairs because current policy approaches do not address the intersection of Indigenous and European political worlds. This paper responds to this challenge by providing a heuristic device for delineating Settler and Indigenous Australian political ontologies and considering their interaction. It first evokes Settler and Aboriginal ontologies as respectively biopolitical (focused through life) and terrapolitical (focused through land). These ideal types help to identify important differences that inform current governance challenges. The paper discusses the entwinement of these traditions as a story of biopolitical dominance wherein Aboriginal people are governed as an “included-exclusion” within the Australian political community. Despite the overall pattern of dominance, this same entwinement offers possibilities for exchange between biopolitics and terrapolitics, and hence for breaking the recurrent crises of Indigenous affairs. ∗ Thanks to Lyndon Murphy, Rebecca Duffy, Bree Blakeman and two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on earlier drafts. 1 Introduction Australian Indigenous affairs is characterised by a pattern of recurrent crises. Summits are called and ministers make bold pronouncements: a “new approach” is required and duly devised. Efforts to address “Aboriginal disadvantage” and “Third World conditions” are revised and redoubled. But in continuation of an overall pattern, the renewed efforts are likely to be subject to future revision. It seems that, as Jeremy Beckett (1988, 14) noted in the year of the Australian bicentenary, colonisation and its outcomes ‘have produced a level of poverty and deprivation that is beyond the capacity of the market or the welfare apparatus to remedy’. -

Atomic Thunder: the Maralinga Story

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Members of the Editorial Board Maria Nugent (Chair), Tikka Wilson (Secretary), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Co-Editor), Liz Conor (Co-Editor), Luise Hercus (Review Editor), Annemarie McLaren (Associate Review Editor), Rani Kerin (Monograph Editor), Brian Egloff, Karen Fox, Sam Furphy, Niel Gunson, Geoff Hunt, Dave Johnston, Shino Konishi, Harold Koch, Ann McGrath, Ewen Maidment, Isabel McBryde, Peter Read, Julia Torpey, Lawrence Bamblett. Editors: Ingereth Macfarlane and Liz Conor; Book Review Editors: Luise Hercus and Annemarie McLaren; Copyeditor: Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. -

Success Stories in Indigenous Health

SUCCESS STORIES IN INDIGENOUS HEALTH A showcase of successful Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health projects Australians for Native Title & Reconciliation Acknowledgements ANTaR acknowledges the generous gave us the ground rules to identify these Colyer, Kathleen Gilbert, Glenn Giles, assistance of the spokespeople and stories from the hundreds of inspiring Melanie Gillbank, Gary Highland, Christine communities described in this collection. projects from which we could have Howes, Jean Murphy, Kate Sullivan and Thank you for sharing your knowledge chosen. Sue Storry from ANTaR for all that they with us. Also: have done to pull the booklet together. Associate Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver Sally Fitzpatrick for editing the volume as and Jill Guthrie from the Muru Marri ANTaR’s Indigenous Reference Group and well as researching and writing the stories Indigenous Health Unit, University of our partners in the Indigenous Health with co-writers James Iliff e, Monique NSW, for their ongoing support and Rights campaign including the Aboriginal Zammit and Dr Silas Taylor. advice. Professor Judy Atkinson, Professor & Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Unit Ken Wyatt, Dr Alan Cass, Dr Phyll Dance, of the Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Cindy Shannon, John Wakerman, Peter Dr Hilton Immerman, Dr David Thomas, Commission, the Australian Indigenous Hill, Tony Barnes, Robert Griew and Mike Cooper, Pieta Laut, John Paterson, Doctors’ Association, the Australian Ann Ritchie for their valuable work Tristan Ray, Andrew Reefman and Jeff Medical Association, the National Achievements in Aboriginal and Torres Standen for assistance throughout the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Strait Islander Health: Final Report (Volume project. Organisation, Oxfam and the Public 1) produced by the Co-operative Research Health Association of Australia. -

Alice Springs Convention Centre National Child Protection Clearing House 4

Workshops Workshop options - Group A – Saturday morning NATIONAL 1. Providing a secure and healthy emotional environment and secure attachments in out of home care - Susan Von Leonhardi 2. Cross Cultural Fostering - Jodie Satour and Robyn Donnelly and Kinship care - Mapping our progress in Central Australia - Anne Williams, David Ross and Colleen Hays 3. Your stories - Arts intervention models for Life Story work facilitation - CREATE (Rob Ball and others) 4. Is anyone listening to me? Effective Support systems - What they are and what they definitely are not? - Heather Lovatt and FOSTER CARE CONFERENCE What makes for best practice in foster carers working with birth families - Views from a research study - Ros Thorpe and Chris Klease 5. Domestic Violence - Chris Burke 2005 6. Aboriginal foster care policy and issues - Secretariat for National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC) and Foster Care policy issues - Australian Foster Care Assocation Workshop options - Group B – Saturday afternoon Friday 29th July - Sunday 31st July 2005 1. Training and assessment of Indigenous carers - SNAICC, Aboriginal Family Support Services (AFFS) and Yourganup panel and You make the difference - Recruiting foster carers in SA - Karyn Webb and Alisa Marshall 2. Interpreting behaviour through a Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder lens - Childhood growth and development & neurological aspects of FASD and how that impacts on behaviour including strategies for success - Sue Miers and Lorian Hays 3. Indigenous Communities and out of home care: Models of Best Practice - Daryl Higgins, Nicholas Richardson and Leah Bromfield, Alice Springs Convention Centre National Child Protection Clearing House 4. Support in Kith and Kin - Cas O’Neill and Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia Learning from each other - Kinship care - It’s all relative - Susie and Chelsea Edwards 5.