Haka on the Horizon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cultural Diffusion in Creating Kiwi Culture: the Role of Rugby

The Role of Cultural Diffusion in Creating Kiwi Culture: The Role of Rugby . Forms of Cultural Diffusion . Spread of Rugby . Combining Cultures Cultural diffusion . Spatial spread of learned ideas, innovations, and attitudes. Each cultural element originates in one or more places and then spreads. Some spread widely, others remain confined to an area of origin. Barriers to diffusion . Absorbing barriers completely halt diffusion. Can be political, economic, cultural, technological . More commonly barriers are permeable, allowing part of the innovation wave to diffuse, but acting to weaken and retard the continued spread. Expansion diffusion . Culture/Ideas spread throughout a population from area to area. Subtypes: 1. Hierarchical diffusion: ideas leapfrog from one node to another temporarily bypassing some 2. Contagious diffusion: wavelike, like disease 3. Stimulus diffusion: specific trait rejected, but idea accepted 4. Relocation diffusion occurs when individuals migrate to a new location carrying new ideas or practices with them Cultural diffusion Combining A Diffused Cultural Trait With A Local/Native Cultural Trait: The Haka New Zealand-Polynesia UNC 7300 miles Football (soccer) Football (rugby league) Football (rugby) Football (rugby union) Football (American Football) Football (Australian Rules Football) THE HAKA Ka mate! Ka mate! Ka ora! Ka ora! 1884 - A New Zealand team in New South Ka mate! Ka mate! Ka ora! Ka ora! Wales used a Maori war cry to introduce Tenei te tangata puhuru huru itself to its opponents before each of its Nana nei i tiki mai matches. Whakawhiti te ra A upa … ne! ka upa … ne! A Sydney newspaper reported: A upane kaupane whiti te ra! "The sound given in good time and union Hi! by 18 pairs of powerful lungs was sometimes tremendous. -

Newsletter Spring 2013 Issue

新 西 籣 東 增 會 館 THE TUNG JUNG ASSOCIATION OF NZ INC PO Box 9058, Wellington, New Zealand www.tungjung.org.nz Newsletter Spring 2013 issue ______ —— The Tung Jung Association of New Zealand Committee 2012—2013 President Brian Gee 566 2324 Membership Kirsten Wong 971 2626 Vice President Gordon Wu 388 3560 Immediate past Property Joe Chang 388 9135 president Willie Wong 386 3099 Brian Gee 566 2324 Secretaries- Gordon Wu 388 3560 English Sam Kwok 027 8110551 Chinese Peter Wong 388 5828 Newsletter Gordon Wu 388 3560 Peter Moon 389 8819 Treasurer Robert Ting 478 6253 Assistant treasurer Virginia Ng 232 9971 Website Gordon Wu 388 3560 Peter Moon 389 8819 Social Elaine Chang 388 9135 Willie Wong 386 3099 Public Valerie Ting 565 4421 relations Gordon Wu Please visit our website at http://www.tungjung.org.nz 1 President’s report ………….. Hi Tung Jung Members Trust this newsletter finds you all well. In the past few months in Wellington, we have experienced a huge storm with wind gusts exceeding the Wahine storm and causing much damage and disruption to our city. On top of this we were hit with a number of earthquakes which really shook us up and left us wondering when the proverbial Big One would come. It was however good for the supermarkets because everyone stocked up on bottled water, candles, canned foods, batteries and torches. OK for some? Midwinter Seniors’ Yum Cha In June the Association held a Midwinter Seniors Yum Cha at Dragon Restaurant. It was well attended by over 60 members. -

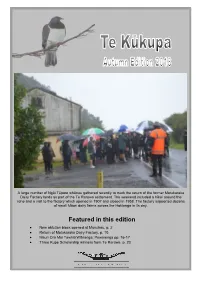

Featured in This Edition

A large number of Ngāi Tūpoto whānau gathered recently to mark the return of the former Motukaraka Dairy Factory lands as part of the Te Rarawa settlement. The weekend included a hīkoi around the rohe and a visit to the factory which opened in 1907 and closed in 1958. The factory supported dozens of small Māori dairy farms across the Hokianga in its day. Featured in this edition New ablution block opened at Manukau, p. 2 Return of Motukaraka Dairy Factory, p. 10 Mauri Ora Mai Tawhiti Wānanga; Pawarenga pp. 16-17 Three Kupe Scholarship winners from Te Rarawa. p. 20 Manukau Marae Ko Orowhana te maunga Ko Taunaha te tupuna Ko Kohuroa te waihīrere Ka Rangiheke me Te Uwhiroa ngā awa Ko Ōwhata te wahapū Ko Ngāti Hine me Te Patu Pīnaki ngā hapū New ablution block opened Manukau Marae committee wish to recog- Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi; engari, he nise and thank the contractor, Jennian toa takitini. (This is not the work of one, but Homes; as well as Foundation North (Cyril the work of many.) The completion and ded- Howard,) and Internal Affairs/ Lotteries ication of the new ablution block at Manu- (Anna Pospisil) for funding; and Te kau Marae epitomises this whakatauki. It Runanga o Te Rarawa, and the local project was a pleasure to see all those that have team that was led by Dave Smith and Caro- supported the project at the opening in line Rapana. Following the opening and mi- March. The new facilities are great notwith- himihi, our manuhiri were treated to a won- standing the challenges. -

APO Annual Report 2017

AUCKLAND PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA 2017 ANNUAL REPORT AUCKLAND PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra is New Zealand’s full-time professional Metropolitan CONTENTS orchestra, serving Auckland’s communities with a comprehensive programme of concerts and education and outreach activities. Chairman’s Report 1 In more than 70 self-presented performances annually, the Chief Executive’s Report 2 APO presents a full season of symphonic work showcasing Premieres in 2017 4 many of the world’s finest classical musicians. Renowned for its innovation, passion and versatility, the APO collaborates with New Zealand Artists Performing some of New Zealand’s most inventive contemporary artists. with the APO in 2017 4 Artistic and Performance Highlights 6 The APO is proud to support both New Zealand Opera and the Royal New Zealand Ballet in their Auckland performances. It Marketing and Sales 7 also works in partnership with Auckland Arts Festival, the New APO Connecting 8 Zealand International Film Festival, the Michael Hill International Violin Competition and Auckland War Memorial Museum, among Business Partnerships other organisations. and Development 10 Through its numerous APO Connecting (education, outreach APO Musicians, Management, and community) initiatives the APO offers opportunities to Board and Support Organisations 11 more than 27,000 young people and adults nationwide to Financial Overview 12 engage with and participate in music activities ranging from hip-hop and rock to contemporary and classical. APO Financial Statements 13 APO Funders, Donors More than 250,000 people worldwide experience the orchestra and Supporters 41 live each year with many thousands more reached through recordings, broadcasts and other media. APO Sponsors 45 COVER IMAGE: Steven Logan, Principal Timpanist and Eric Renick, Principal Percussionist (Photo: Adrian Malloch) CHAIRMAN’S REPORT It is my pleasure to report on 2017 on behalf of the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra Board, a year of exciting new opportunities for the orchestra. -

Griffith REVIEW Editon 43: Pacific Highways

Griffith 43 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS GriffithREVIEW43 Pacific Highways ESSAY HINEMOANA BAKER Walking meditations BERNARD BECKETT School report DAVID BURTON A Kiwi feast HAMISH CLAYTON The lie of the land RE KATE DE GOLDI Simply by sailing in a new direction LYNN JENNER Thinking about waves FINLAY MACDONALD Primate city LYNNE McDONALD Cable stations V GREGORY O’BRIEN Patterns of migration ROBERTO ONELL To a neighbour I am getting to know IE ROD ORAM Tectonic Z REBECCA PRIESTLEY Hitching a ride W HARRY RICKETTS On masks and migration JOHN SAKER Born to run CARRIE TIFFANY Reading Geoff Cochrane MATT VANCE An A-frame in Antarctica 43 IAN WEDDE O Salutaris LYDIA WEVERS First, build your hut DAMIEN WILKINS We are all Stan Walker ALISON WONG Pure brightness Highways Pacific ASHLEIGH YOUNG Sea of trees MEMOIR KATE CAMP Whale Road PAMELA ‘JUDY’ ROSS Place in time PETER SWAIN Fitting into the Pacific LEILANI TAMU The beach BRIAN TURNER Open road MoreFREE great eBOOKstories and KATE WOODS Postcard from Beijing poetry are available in PACIFIC HIGHWAYS Vol. 2 REPORTAGE as a free download at SALLY BLUNDELL Amending the map www.griffithreview.com STEVE BRAUNIAS On my way to the border GLENN BUSCH Portrait of an artist FICTION WILLIAM BRANDT Getting to yes EMILY PERKINS Waiheke Island CK STEAD Anxiety POETRY JAMES BROWN GEOFF COCHRANE CLIFF FELL PACIFIC DINAH HAWKEN YA-WEN HO BILL MANHIRE GREGORY O’BRIEN HIGHWAYS VINCENT O’SULLIVAN CO-EDITED BY JULIANNE SCHULTZ ‘Australia’s most stimulating literary journal.’ & LLOYD JONES Cover design: Text Publishing design: Text Cover Canberra Times JOURNAL QUARTERLY Praise for Griffith REVIEW ‘Essential reading for each and every one of us.’ Readings ‘A varied, impressive and international cast of authors.’ The Australian ‘Griffith REVIEW is a must-read for anyone with even a passing interest in current affairs, politics, literature and journalism. -

Navigating the Waka of Māori Community Development

New Zealand Journal of History, 49, 1 (2015) Navigating The Waka Of Māori Community Development PANGURU, ‘THE MAORI AFFAIRS’ AND ANTHROPOLOGY IN THE 1950S BETWEEN 1954 AND 1957, THE PEOPLE OF PANGURU in North Hokianga participated in a community development experiment administered by the Department of Maori Affairs. The Panguru Community Development Pilot Project, as it was officially named, was initiated by John Booth, the first anthropologist employed by the department.1 The project signalled an experimental policy shift away from individualistic ‘land development’ to collective ‘people development’. Although the project was a one-off, ‘tri-anthropological’ engagement was not new; throughout the early and mid-twentieth century, anthropology established a role in determining the pace and shape of the state’s assimilation policy, as well as in Māori efforts to revitalize tribal economies. The Panguru project provides a unique window into Māori negotiations with anthropology and the state. At the heart of this complex interaction was a clash of world views about what a ‘modern Maori community’ could and should have been in the 1950s. Although the state increasingly managed the processes of assimilation within the frame of modernity, such a view was peripheral if not irrelevant to the people of Panguru. Their participation in the project highlights how the leaders and people of Panguru took advantage of what they believed were the most beneficial features of the project. They sought control of their land, resources and economic futures, as well as access to modern technology and ideas. Examining their experience shows how Māori people – at both community and national levels – worked with the state and New Zealand’s emergent anthropological community, and negotiated anthropological theory in order to achieve divergent goals in the mid-twentieth century. -

Rekohu Report (2016 Newc).Vp

Rekohu REKOHU AReporton MorioriandNgatiMutungaClaims in the Chatham Islands Wa i 6 4 WaitangiTribunalReport2001 The cover design by Cliff Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfoldsinapatternnotyetcompletelyknown AWaitangiTribunalreport isbn 978-1-86956-260-1 © Waitangi Tribunal 2001 Reprinted with corrections 2016 www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by Printlink, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Set in Adobe Minion and Cronos multiple master typefaces e nga mana,e nga reo,e nga karangaranga maha tae noa ki nga Minita o te Karauna. ko tenei te honore,hei tuku atu nga moemoea o ratou i kawea te kaupapa nei. huri noa ki a ratou kua wheturangitia ratou te hunga tautoko i kokiri,i mau ki te kaupapa,mai te timatanga,tae noa ki te puawaitanga o tenei ripoata. ahakoa kaore ano ki a kite ka tangi,ka mihi,ka poroporoakitia ki a ratou. ki era o nga totara o Te-Wao-nui-a-Tane,ki a Te Makarini,ki a Horomona ma ki a koutou kua huri ki tua o te arai haere,haere,haere haere i runga i te aroha,me nga roimata o matou kua mahue nei. e kore koutou e warewaretia. ma te Atua koutou e manaaki,e tiaki ka huri Contents Letter of Transmittal _____________________________________________________xiii 1. Summary 1.1 Background ________________________________________________________1 1.2 Historical Claims ____________________________________________________4 1.3 Contemporary Claims ________________________________________________9 1.4 Preliminary Claims __________________________________________________11 1.5 Rekohu, the Chatham Islands, or Wharekauri? _____________________________12 1.6 Concluding Remarks ________________________________________________13 2. -

The Metabolic Demands of Culturally-Specific

THE METABOLIC DEMANDS OF CULTURALLY-SPECIFIC POLYNESIAN DANCES by Wei Zhu A thesis submitted in partial FulFillment oF the requirements For the degree of Master oF Science in Health and Human Development MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Wei Zhu 2016 All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 Historical Background ............................................................................................... 1 Statement oF Purpose ............................................................................................... 3 SigniFicance oF Study ................................................................................................. 3 Hypotheses ............................................................................................................... 4 Limitations ................................................................................................................ 5 Delimitations ............................................................................................................. 5 2. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ..................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 6 Health Status in NHOPI ............................................................................................. 6 PA – A Strategy -

Natural Areas of Aupouri Ecological District

5. Summary and conclusions The Protected Natural Areas network in the Aupouri Ecological District is summarised in Table 1. Including the area of the three harbours, approximately 26.5% of the natural areas of the Aupouri Ecological District are formally protected, which is equivalent to about 9% of the total area of the Ecological District. Excluding the three harbours, approximately 48% of the natural areas of the Aupouri Ecological District are formally protected, which is equivalent to about 10.7% of the total area of the Ecological District. Protected areas are made up primarily of Te Paki Dunes, Te Arai dunelands, East Beach, Kaimaumau, Lake Ohia, and Tokerau Beach. A list of ecological units recorded in the Aupouri Ecological District and their current protection status is set out in Table 2 (page 300), and a summary of the site evaluations is given in Table 3 (page 328). TABLE 1. PROTECTED NATURAL AREA NETWORK IN THE AUPOURI ECOLOGICAL DISTRICT (areas in ha). Key: CC = Conservation Covenant; QEII = Queen Elizabeth II National Trust covenant; SL = Stewardship Land; SR = Scenic Reserve; EA = Ecological Area; WMR = Wildlife Management Reserve; ScR = Scientific Reserve; RR = Recreation Reserve; MS = Marginal Strip; NR = Nature Reserve; HR = Historic Reserve; FNDC = Far North District Council Reserve; RFBPS = Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society Site Survey Status Total Total no. CC QEII SL SR EA WMR ScR RR MS NR HR FNDC RFBPS prot. site area area Te Paki Dunes N02/013 1871 1871 1936 Te Paki Stream N02/014 41.5 41.5 43 Parengarenga -

Tui Motu Interislands Monthly Independent Catholic Magazine June 2013 | $6

Tui Motu InterIslands monthly independent Catholic magazine June 2013 | $6 HONE PAPITA RAUKURA ‘RALPH’ HOTERE . editorial a rare diamond hildren are always curious . Daniels was destined for great things spirits soar because of the beauty As a boy of seven or eight, I from birth . A bright child, Ralph and aesthetic power they bring to was fascinated by my moth- excelled easily at primary school, their art . They stop us in our tracks . Cer’s diamond engagement ring . It was winning a boarding scholarship to Ralph’s ventures into such vital issues an unexceptional gold ring set with St . Peter’s Maori School (now Hato as the plight of the Algerian people three small diamonds . However, now Petera College) . Going to Auckland in their search for freedom from I can see why I was entranced . The Teachers College for two years seemed colonial domination, the Cuban mis- exceptional quality of these jewels a logical step forward . And from there, sile crisis, and proposed aluminium shone forth in their beauty and his known ability at art meant he was smelter at Aramoana are at the heart diaphanous colours . A jeweller told sent, in 1952, to Dunedin Teachers of this man’s work . He combined me that the natural quality of the College to train as an arts adviser in in his unique way a Māori heritage diamonds has been enhanced by fine schools . Such is the background of and a thoughtful but fiery spirit that bevelling of the jewels themselves — the man we honour . exposed what was not right in our ‘nature and nurture’ combined to A most important reason for world . -

The Misappropriation of the Haka: Are the Current Legal Protections Around Mātauranga Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand Sufficient?

523 THE MISAPPROPRIATION OF THE HAKA: ARE THE CURRENT LEGAL PROTECTIONS AROUND MĀTAURANGA MĀORI IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND SUFFICIENT? Isabella Tekaumārua Wilson* This article analyses the protections the New Zealand intellectual property framework provides for the haka and mātauranga Māori. Part II of this article defines the key terms of "misappropriation", "traditional knowledge" and "mātauranga Māori" in order for the reader to fully understand these concepts in an indigenous, and specifically Māori, context. Part III of this article discusses the importance and significance of haka in Māori culture, particularly looking at the history and significance of Ka Mate, the most well-known haka in New Zealand and the world. Examples of different companies, both New Zealand and internationally-owned, using the haka for commercial benefit are analysed to establish whether or not their use of the haka is misappropriation, and if so, the harm this misappropriation has caused Māori. Part IV discusses the current legal protections New Zealand provides for mātauranga Māori and whether they sufficiently protect the haka and mātauranga Māori generally. It will assess the Haka Ka Mate Attribution Act 2014 as a case study. Part V outlines the limitations of the intellectual framework. Part VI of this article looks to what legal protections would be sufficient to protect against the misappropriation of the haka and mātauranga Māori generally. I INTRODUCTION Kua tae mai te wa, e whakapuru ai tatou i nga kowhao o te waka. The time has come where we must plug the holes in the canoe. * Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei and Waikato-Tainui. 524 (2020) 51 VUWLR All over the world, indigenous communities are seeking greater control of their culture.1 Māori culture has been suppressed in Aotearoa New Zealand for decades, and now, non-Māori businesses and individuals, in New Zealand and overseas, have begun to exploit Māori culture to promote and enhance their business dealings and sell their products. -

Pe Structure Cf Tongan Dance a Dissertation

(UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY P E STRUCTURE CF TONGAN DANCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION CF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FUIFILDffiNT CF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE CF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ANTHROPOLOGY JUNE 1967 By _\G Adrienne L? Kaeppler Dissertation Committee: Alan Howard, Chairman Thomas W. Maretzki Roland W. Force Harold E. McCarthy Barbara B. Smith PREFACE One of the most conspicious features of Polynesian life and one that has continually drawn comments from explorers, missionaries, travelers, and anthropologists is the dance. These comments have ranged from outright condemnation, to enthusiastic appreciation. Seldom, however, has there been any attempt to understand or interpret dance in the total social context of the culture. Nor has there been any attempt to see dance as the people themselves see it or to delineate the structure of dance itself. Yet dance has the same features as any artifact and can thus be analyzed with regard both to its form and function. Anthropologists are cognizant of the fact that dance serves social functions, for example, Waterman (1962, p. 50) tells us that the role of the dance is the "revalidation and reaffirmation of the aesthetic, religious, and social values shared by a human society . the dance serves as a force for social cohesion and as a means to achieve the cultural continuity without which no human community can persist.” However, this has yet to be scientifically demonstrated for any Pacific Island society. In most general ethnographies dance has been passed off with remarks such as "various movements of the hands were used," or "they performed war dances." In short, systematic study or even satisfactory description of dance in the Pacific has been virtually neglected despite the significance of dance in the social relations of most island cultures.