R,1.,\~,JILA LIBRAR Summer Institute of Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [Cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1146/a-sociolinguistic-profile-of-the-kyoli-cori-cry-language-of-kaduna-state-nigeria-51146.webp)

A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [Cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2020-012 A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria Ken Decker, John Muniru, Julius Dabet, Benard Abraham, Jonah Innocent A Sociolinguistic Profile of the Kyoli (Cori) [cry] Language of Kaduna State, Nigeria Ken Decker, John Muniru, Julius Dabet, Benard Abraham, Jonah Innocent SIL International® 2020 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2020-012, October 2020 © 2020 SIL International® All rights reserved Data and materials collected by researchers in an era before documentation of permission was standardized may be included in this publication. SIL makes diligent efforts to identify and acknowledge sources and to obtain appropriate permissions wherever possible, acting in good faith and on the best information available at the time of publication. Abstract This report describes a sociolinguistic survey conducted among the Kyoli-speaking communities in Jaba Local Government Area (LGA), Kaduna State, in central Nigeria. The Ethnologue (Eberhard et al. 2020a) classifies Kyoli [cry] as a Niger-Congo, Atlantic Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Plateau, Western, Northwestern, Hyamic language. During the survey, it was learned that the speakers of the language prefer to spell the name of their language <Kyoli>, which is pronounced as [kjoli] or [çjoli]. They refer to speakers of the language as Kwoli. We estimate that there may be about 7,000 to 8,000 speakers of Kyoli, which is most if not all the ethnic group. The goals of this research included gaining a better understanding of the role of Kyoli and other languages in the lives of the Kwoli people. Our data indicate that Kyoli is used at a sustainable level of orality, EGIDS 6a. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

A Study of the Badjaos in Tawi- Tawi, Southwest Philippines Erwin Rapiz Navarro

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Living by the Day: A Study of the Badjaos in Tawi- Tawi, Southwest Philippines Erwin Rapiz Navarro Master’s thesis in Peace and Conflict Transformation – November 2015 i Abstract This study examines the impacts of sedentarization processes to the Badjaos in Tawi-Tawi, southwest of the Philippines. The study focuses on the means of sedentarizing the Badjaos, which are; the housing program and conditional cash transfer fund system. This study looks into the conditionalities, perceptions and experiences of the Badjaos who are beneficiaries of the mentioned programs. To realize this objective, this study draws on six qualitative interviews matching with participant-observation in three different localities in Tawi-Tawi. Furthermore, as a conceptual tool of analysis, the study uses sedentarization, social change, human development and ethnic identity. The study findings reveal the variety of outcomes and perceptions of each program among the informants. The housing project has made little impact to the welfare of the natives of the region. Furthermore, the housing project failed to provide security and consideration of cultural needs of the supposedly beneficiaries; Badjaos. On the other hand, cash transfer fund, though mired by irregularities, to some extent, helped in the subsistence of the Badjaos. Furthermore, contentment, as an antithesis to poverty, was being highlighted in the process of sedentarization as an expression of ethnic identity. Analytically, this study brings substantiation on the impacts of assimilation policies to indigenous groups, such as the Badjaos. Furthermore, this study serves as a springboard for the upcoming researchers in the noticeably lack of literature in the study of social change brought by sedentarization and development policies to ethnic groups in the Philippines. -

Six Years of MTB MLE: Revisiting Teachers' Language Attitude

Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies Vol. 1, No. 3 (Special Issue), (2018) ISSN 2651-6691 (Print) ISSN 2651-6705 (Online) Six years of MTB MLE: Revisiting Teachers’ Language Attitude towards the Teaching of Chavacano Ali G. Anudin Philippine Normal University, Manila, Philippines Abstract - To gauge the success of the mother tongue-based multilingual education (MTB-MLE) in the Philippines is tantamount to examining it in a milieu where its citizens speak a number of languages. Zamboanga City is credibly one of the cities in the country identified to be multilingual where its people speak about eight (8) languages, namely: Chavacano, Cebuano-Bisaya, Tausug, Sama, Yakan, Tagalog, Subanen, and Hiligaynon. This study surveys the MTB-MLE program in its sixth year of implementation. Specifically, it attempted to determine the general language attitude of the teacher- respondents in using Chavacano as a language of instruction, and the difficulties they faced in the classroom in using the mother tongue. The data were gathered through qualitative descriptive method using survey questionnaire and interview questions. A total of thirty-eight (38) teachers participated as respondents: thirty-two (32) answered the survey questionnaire, and six (6) partook in accomplishing the interview questions. The respondents all come from one of the biggest public primary school i.e. Don Gregorio Elementary Memorial School (DONGEMS), which is located at the heart of Zamboanga City where the implementation of MTB-MLE was seen to be much difficult since there are eight prevailing languages used by the people within the area. The findings revealed that teachers generally have negative attitude towards the use of Chavacano as language of instruction. -

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal Geography and Demographics 196,722 square Size: kilometers (km2) Population: 14 million (2015) Capital: Dakar Urban: 44% (2015) Administrative 14 regions Divisions: Religion: 95% Muslim 4% Christian 1% Traditional Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2015). Note: Population and percentages are rounded. Literacy Projected 2013 Primary School 2015 Age Population (aged 2.2 million Literacy a a 7–12 years): Rates: Overall Male Female Adult (aged 2013 Primary School 56% 68% 44% 84%, up from 65% in 1999 >15 years) GER:a Youth (aged 2013 Pre-primary School 70% 76% 64% 15%,up from 3% in 1999 15–24 years) GER:a Language: French Mean: 18.4 correct words per minute When: 2009 Oral Reading Fluency: Standard deviation: 20.6 Sample EGRA Where: 11 regions 18% zero scores Resultsb 11% reading with ≥60% Reading comprehension Who: 687 P3 students Comprehension: 52% zero scores Note: EGRA = Early Grade Reading Assessment; GER = Gross Enrollment Rate; P3 = Primary Grade 3. Percentages are rounded. a Source: UNESCO (2015). b Source: Pouezevara et al. (2010). Language Number of Living Languages:a 210 Major Languagesb Estimated Populationc Government Recognized Statusd 202 DERP in Africa—Reading Materials Survey Final Report 47,000 (L1) (2015) French “Official” language 3.9 million (L2) (2013) “National” language Wolof 5.2 million (L1) (2015) de facto largest LWC Pulaar 3.5 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Serer-Sine 1.4 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Maninkakan (i.e., Malinké) 1.3 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Soninke 281,000 (L1) (2015) “National” language Jola-Fonyi (i.e., Diola) 340,000 (L1) “National” language Balant, Bayot, Guñuun, Hassanya, Jalunga, Kanjaad, Laalaa, Mandinka, Manjaaku, “National” languages Mankaañ, Mënik, Ndut, Noon, __ Oniyan, Paloor, and Saafi- Saafi Note: L1 = first language; L2 = second language; LWC = language of wider communication. -

Language Classification in the Ethnologue and Its Consequences (Paper)

Sarah E. Cornwell The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada Language Classification in The Ethnologue and its Consequences (Paper) Abstract: The Ethnologue is a widely used classificatory standard for the world’s 7000+ natural languages. However, the motives and processes used by The Ethnologue’s governing body, SIL International, have come under criticism by linguists. This paper investigates how The Ethnologue answers the question “What is a language?” through the theoretical lens presented by Bowker and Star in Sorting Things Out (1999) and presents some consequences of those classificatory decisions. 1. Introduction Language is central to human culture and experience. It is the central core of our communicative capacity, running through all media of communication. Due to this essential role, there is a need to classify and count languages and their speakers1. Governments need to communicate with citizens, libraries need to catalogue books by language, and search engines need to return webpages in the appropriate language for each searcher. For these reasons among others, there is a strong institutional need for a standardized classification structure and labelling system for languages. The most widespread current classificatory infrastructure for languages is based on The Ethnologue. This essay will critically evaluate The Ethnologue using the Foucauldian theory developed for investigating classification structures by Bowker and Star (1999) in Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences. 2. The Ethnologue The Ethnologue is a catalogue of all the world’s languages. First compiled in 1951, The Ethnologue is currently in its 20th edition and contains descriptions of 7099 living languages (2017). Since 1997, The Ethnologue has been available freely online and widely accessible (Simons & Fennig, 2017). -

NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries

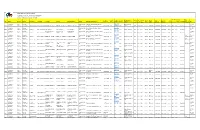

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO.: X- NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries - CY 2020 Other Plant Locations Status Mine Site Mine Mine Site E- Head Office Head Office Head Office E- Head Office Mine Site Mailing Type of Permit Date Date of Area municipality, Non- Telephon Site Fax mail barangay Year Region Mineral Province Municipality Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Head Office Mailing Address Telephone No. Fax No. mail Address Website (hectares) province Producing TIN Address e No. No. Address Permit Number Approved Expiration Producing donjieanim 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Poblacion, Sapang Dalaga, Misamis as@yahoo Dioyo, Sapang 191-223- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Sapang Dalaga Sand and Gravel ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ager Occidental 9654955493 N/A .com N/A Dalaga N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-07-19 11/10/2019 10/10/2020 1.00 N/A N/A Producing 205 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man South Western, Calamba, Misamis ljcyap7@g 432-503- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. ager Occidental 9466875752 N/A mail.com N/A Sulipat, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-18-19 04/02/2020 03/02/2021 1.9524 N/A N/A Producing 363 maconsuel 10-Northern Non- Misamis ROGELIO, MARIA ROGELIO, MA. ROGELIO, MA. Proprietor/Man Northern Poblacion, Calamba, Misamis orogelio@ 325-550- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel CONSUELO A. CONSUELO A. CONSUELO ager Occidental 9464997271 N/A gmail.com N/A Solinog, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-03-20 24/06/2020 23/06/2021 1.094 N/A N/A Producing 921 noel_pagu 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Southern Poblacion, Plaridel, Misamis e@yahoo. -

Mapping India's Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and Its

Mapping India’s Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and its Exclusion in the Indian Census Dr. Shivakumar Jolad1 and Aayush Agarwal2 1FLAME University, Lavale, Pune, India 2Centre for Social and Behavioural Change, Ashoka University, New Delhi, India Abstract In this article, we critique the process of linguistic data enumeration and classification by the Census of India. We map out inclusion and exclusion under Scheduled and non-Scheduled languages and their mother tongues and their representation in state bureaucracies, the judiciary, and education. We highlight that Census classification leads to delegitimization of ‘mother tongues’ that deserve the status of language and official recognition by the state. We argue that the blanket exclusion of languages and mother tongues based on numerical thresholds disregards the languages of about 18.7 million speakers in India. We compute and map the Linguistic Diversity Index of India at the national and state levels and show that the exclusion of mother tongues undermines the linguistic diversity of states. We show that the Hindi belt shows the maximum divergence in Language and Mother Tongue Diversity. We stress the need for India to officially acknowledge the linguistic diversity of states and make the Census classification and enumeration to reflect the true Linguistic diversity. Introduction India and the Indian subcontinent have long been known for their rich diversity in languages and cultures which had baffled travelers, invaders, and colonizers. Amir Khusru, Sufi poet and scholar of the 13th century, wrote about the diversity of languages in Northern India from Sindhi, Punjabi, and Gujarati to Telugu and Bengali (Grierson, 1903-27, vol. -

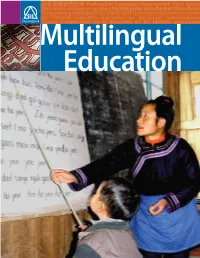

The Components of Sustainable Multilingual Education Programs

A Two-Way Bridge The Components of Sustainable Multilingual Education Programs Studies demonstrate that learning is most effective when the instruction is received in the language the learner knows best. This simple truth extends from basic reading and writing skills in the first language to second language acquisition. In multilingual education programs (MLE) that start with the mother tongue, learners use their own language for learning in the early grades, while also learning the official language as a classroom subject. As learners gain competence in understanding, speaking, reading and writing the language of education, teachers begin using it for instruction. This instructional bridge between the community language and the language of wider communication enables learners—children and adults alike—to meet their broader multilingual goals while retaining their local language and culture. This booklet addresses several important aspects of MLE: ■ The voices of ethnolinguistic minority communities are often not heard. Therefore, advocacy is appropriate for these communities to meet their MLE needs. ■ Conventional instructional methods are not adequate for MLE programs. Educators at both community and national levels need to develop their capacity to design and implement MLE programs. ■ Developing a writing system for a non-dominant language is a challenging but essential early step in developing an MLE program. ■ MLE not only requires the commitment and resources of the local community, but also the resources and expertise available from government agencies, NGOs or others. Resource linking brings the partners together so that each one contributes its own particular resources. ■ MLE gives children and adults a firm foundation for continuing to learn throughout their lives. -

English Planning for Global Cooperation in Sign Language Development Through Networks, Finland, the US, Colombia and Japan Consultants and Resources

SIL International 2009 Partners in Language Development UPDATE YEARS 1934–2009 “No one has ever seen a book in our language before.” Until this year, the Koda community in Bangladesh did not have a written form of their language. Some Koda people thought it was impossible to write their language. A cooperative education and development program for this community was started by Food for the Hungry and SIL. In 2009, a group of eager Koda men met several times with SIL staff to make decisions about a writing system for their language. The men—some of whom had only attended school for two years—participated in an orthography workshop with SIL consultants and began to write in their own language. They worked together to identify the speech sounds that are the same as in Bangla (the national language), the several sounds that are different, and how to Each workshop represent each sound in an alphabet—the first step towards uniform spelling. participant wrote When workshop participants were asked to write stories about their daily lives and a story in Koda and culture, they responded, “We have never written a story before.” But by the end of made his own book. These men have the workshop, each participant had written a short story and made his own book to started to fulfill their take back to his village—an achievement that gave them confidence and increased community’s desire to self-esteem. protect and preserve SIL grew out of one man’s concern for people speaking languages that lacked written their language. -

A Sketch of the Linguistic Geography of Signed Languages in the Caribbean1,2

OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 38 A SKETCH OF THE LINGUISTIC GEOGRAPHY OF SIGNED LANGUAGES IN THE CARIBBEAN Ben Braithwaite The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine June 2017 SCL OCCASIONAL PAPERS PAPER NUMBER 38—JUNE 2017 Edited by Ronald Kephart (2014–2016) and Joseph T. Farquharson (2016–2018), SCL Publications Officers Copy editing by Sally J. Delgado and Ronald Kephart Proofreading by Paulson Skerritt and Sulare Telford EDITORIAL BOARD Joseph T. Farquharson The University of the West Indies, Mona (Chair) Janet L. Donnelly College of the Bahamas David Frank SIL International Ronald Kephart University of North Florida Salikoko S. Mufwene University of Chicago Ian E. Robertson The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Geraldine Skeete The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Donald C. Winford Ohio State University PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY FOR CARIBBEAN LINGUISTICS (SCL) c/o Department of Language, Linguistics and Philosophy, The University of the West Indies, Mona campus, Kingston 7, Jamaica. <www.scl-online.net> © 2017 Ben Braithwaite. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. ISSN 1726–2496 THE LINGUISTIC GEOGRAPHY OF SIGNED LANGUAGES 3 A Sketch of the Linguistic Geography of Signed Languages in the Caribbean1,2 Ben Braithwaite The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine 1. Introduction HE Caribbean… is the location of almost every type of linguistic “Tphenomenon, and of every type of language situation. For example, trade and contact jargons, creole languages and dialects, ethnic vernaculars, and regional and nonstandard dialects are all spoken. There are also ancestral languages used for religious purposes…, regional standards, and international standards. -

INDIGENOUS GROUPS of SABAH: an Annotated Bibliography of Linguistic and Anthropological Sources

INDIGENOUS GROUPS OF SABAH: An Annotated Bibliography of Linguistic and Anthropological Sources Part 1: Authors Compiled by Hans J. B. Combrink, Craig Soderberg, Michael E. Boutin, and Alanna Y. Boutin SIL International SIL e-Books 7 ©2008 SIL International Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008932444 ISBN: 978-155671-218-0 Fair Use Policy Books published in the SIL e-Books series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor Mary Ruth Wise Volume Editor Mae Zook Compositor Mae Zook The 1st edition was published in 1984 as the Sabah Museum Monograph, No. 1. nd The 2 edition was published in 1986 as the Sabah Museum Monograph, No. 1, Part 2. The revised and updated edition was published in 2006 in two volumes by the Malaysia Branch of SIL International in cooperation with the Govt. of the State of Sabah, Malaysia. This 2008 edition is published by SIL International in single column format that preserves the pagination of the 2006 print edition as much as possible. Printed copies of Indigenous groups of Sabah: An annotated bibliography of linguistic and anthropological sources ©2006, ISSN 1511-6964 may be obtained from The Sabah Museum Handicraft Shop Main Building Sabah Museum Complex, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah,