M0051600.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

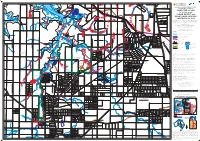

FLOOD EXTENT and PEAK FLOOD SURFACE CONTOURS for 2100

707500E 710000E 712500E 715000E 717500E 720000E 722500E 725000E 11 1 0 2 26 23 18 Middle Arm Road 19 22 BLACKMORE 17 19 27 25 18 1 NOONAMAH 2 19 ELIZABETH and BLACKMORE RIVER 23 3 5 24 20 CATCHMENTS — Sheet 2 25 4 20 4 COMPUTED 1% AEP RIVER 3 Aquiculture Farm Ponds 26 26 21 21 22 (1 in 100 year) 5 Middle Arm Boat Ramp 25 6 24 7 1 23 FLOOD EXTENT and 2 8 22 16 14 18 23 22 9 15 20 13 21 PEAK FLOOD SURFACE 24 10 1 19 12 17 20 23 CONTOURS for 2100 1 3 4 18 25 6 11 21 24 This map shows the Q100 flood and floodway extents caused by a 1% Annual 1.5 10 2 19 1.25 5 Exceedance Probability (AEP) Flood event over the Elizabeth and Blackmore 8600000N 8600000N 1.25 2 25 Keleson Road River Catchments. The extent of flooding shown on this map is indicative only, 17 Middle Arm Road 2 2 Strauss Field 26 hence, approximate. This map is available for sale from: 3 1.5 9 26 3 27 Land Information Centre, 1 1 8 27 3 1 2 Department of Lands, Planning and the Environment 3 1 3 7 16 1.5 1 3rd Floor NAB House, 71 Smith Street, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0800 28 29 29 Finn Road Finn 1.25 T: (08) 8995 5300 Email: [email protected] 6 30 2 28 31 GPO Box 1680, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0801. 3 31 15 4 5 14 27 33 This map is also available online at: 7 32 30 RIVER 6 7 8 10 35 www.nt.gov.au/floods http://nrmaps.nt.gov.au 9 13 11 12 8 26 32 Legend 2.5 4 5 25 34 3 24 6 Flood extent 3 7 24 8 23 Floodway, depth >2 metres (or velocity x depth > 1) 9 23 22 3 1.25 10 Peak flood surface contour, metres AHD 3 22 10.5 21 Creek channel / flow direction 21 20 Limit of flood mapping -

Fishing the Tiwi Islands Welcome to Our Islands

FISHING THE TIWI ISLANDS WELCOME TO OUR ISLANDS The Tiwi Islands are made up of Melville and Bathurst Islands and numerous smaller, adjacent islands. The Vernon Islands also form part of the Tiwi estate. The Tiwi Traditional Owners and custodians of the area welcome you to our islands and ask that you respect and recognise the cultural importance of our land and waters. CODE OF Conduct RESPect THE RIGHts OF TRADITIONAL OWNERS. • Understand and observe all fishing regulations and no fishing zones. Report illegal fishing activities to the FISHWATCH hotline 1800 891 136 or the Tiwi Land Council HQ at Pickataramoor - 08 8970 9373. • Take no more fish than your immediate needs and carefully return excess or unwanted fish into the water unharmed. • Be courteous to all water users and those who belong to local Tiwi communities. • Respect Tiwi cultural ceremonies. This may mean that a particular area is temporarily closed to access. • Do not land ashore without first obtaining a separate Aboriginal land permit, from the Tiwi Land Council and abide by alcohol restrictions for the area. • Respect sacred sites and do not enter any part of the waters containing identified sacred sites unless specifically permitted to do so by the Tiwi Land Council. • Do not clean or dispose of fish within the vicinity of a community. • Prevent pollution and protect wildlife by removing rubbish and dispose of correctly to avoid potentially entrapping birds and other aquatic creatures. TIWI AND VERNON ISLANDS zones PERMIT FREE access The Tiwi have agreed to provide permit free access to the intertidal waters of the Tiwi and the Vernon Islands in the areas as outlined in the attached map. -

Len Mckenzie Seagrass-Watch HQ

Seagrass-Watch Proceedings of a Workshop for Mapping and Monitoring Seagrass Habitats in North East Arnhem Land, Northern Territory th th 18 – 20 October 2008 Len McKenzie Seagrass-Watch HQ First Published 2008 ©Seagrass-Watch HQ, 2008 Copyright protects this publication. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Disclaimer Information contained in this publication is provided as general advice only. For application to specific circumstances, professional advice should be sought. Seagrass-Watch HQ has taken all reasonable steps to ensure the information contained in this publication is accurate at the time of the survey. Readers should ensure that they make appropriate enquires to determine whether new information is available on the particular subject matter. The correct citation of this document is McKenzie, LJ (2008). Seagrass-Watch: Proceedings of a Workshop for Mapping and Monitoring Seagrass Habitats in North East Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, 18–20 October 2008. (Seagrass-Watch HQ, Cairns). 49pp. Produced by Seagrass-Watch HQ Front cover illustration: Len McKenzie Enquires should be directed to: Len McKenzie Seagrass-Watch Program Leader Northern Fisheries Centre, PO Box 5396 Cairns, QLD 4870 Australia 2 Table of Contents OVERVIEW -

Indigenous Women's Preferences for Climate Change Adaptation And

Indigenous women’s preferences for climate change adaptation and aquaculture development to build capacity in the Northern Territory Final Report Lisa Petheram, Ann Fleming, Natasha Stacey, and Anne Perry Indigenous women’s preferences for climate change adaptation and aquaculture development to build capacity in the Northern Territory Charles Darwin University Northern Territory Government Australian National University LISA PETHERAM, ANN FLEMING, NATASHA STACEY AND ANNE PERRY Published by the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility ISBN: 978-1-925039-55-9 NCCARF Publication 84/13 © 2013 Charles Darwin University This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Please cite this report as: Petheram, L, Fleming, A, Stacey, N and Perry, A 2013 Indigenous women’s preferences for climate change adaptation and aquaculture development to build capacity in the Northern Territory, National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, pp. 44. Acknowledgement This work was carried out with financial support from the Australian Government (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency) and the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility. The views expressed herein are not necessarily the views of the Commonwealth or NCCARF, and neither the Commonwealth nor NCCARF accept responsibility for information or advice contained herein. The role of NCCARF is to lead the research community in a national interdisciplinary effort to generate the information needed by decision-makers in government, business and in vulnerable sectors and communities to manage the risk of climate change impacts. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Warruwi community for their participation and support in this project. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

Weddell Design Forum a Summary of the Outcomes of a Workshop to Explore Issues + Options for the Future City of Weddell

Weddell Design Forum A Summary of the Outcomes of a Workshop to explore Issues + Options for the future City of Weddell 27 September - 1 October 2010 Darwin Convention Centre, Darwin A report to the Northern Territory Government from the consultant leaders of the Weddell Design Forum NOVEMBER 2010 Sustainable, Liveable Tropical, Contents Foreword By 2018, Palmerston will be at capacity, vacant blocks around Introduction 1 Darwin will be developed. Darwin is one of the fastest growing cities in Australia. While much of this growth will be absorbed by The Site + Growth Context 2 in-fill development in Darwin’s existing suburbs and new Palmerston suburbs, we have to start planning now for the future growth of the Community Input 4 Territory. Special Interest Groups 5 Our children and grandchildren will want to live in houses that are in-tune with our environment. They will want to live in a community Key Issues for Weddell 6 that connects people with schools, work, shops and recreation Scenarios 9 facilities that are within walking distance rather than a car ride away. Design Outcomes 10 Achieving this means starting now with good land use planning, setting aside strategic transport corridors and considering the Traffic + Streets 26 physical and social services that will be needed. Indicative Development Costs 27 The Weddell Conference and Design Forum gave us a blank canvas Conclusions + Recommendations 28 on which to paint ideas, consider the picture and recalibrate what we had created. Weddell Design Team 30 It was a unique opportunity rarely experienced by our planning professionals and engineers to consider the views of the community, the imagination of our youth and to engage with such a range of experts. -

Studying Trepangers

2. Studying trepangers Campbell Macknight Trepang has been collected, processed, traded or consumed by diverse groups of people, largely in East and Southeast Asia, but also, importantly, in northern Australia. The producers of trepang, however, have not usually traded their product beyond the initial sale, and the consumers have been different again. This has meant that those who have studied and written about trepang and trepangers have often done so in relative ignorance of other parts of the overall story and the separate literatures that have developed are divided not just by geographical coverage, since there are also distinct differences of discipline and approach. As one continues to explore aspects of the subject, more and more unsuspected vistas open up, especially as the consequences of the activities associated with the industry and of those involved in it are pursued. It is difficult, therefore, to find a central focus in any study of trepang and those involved with its exploitation and use. A fruitful way to analyse our knowledge is to distinguish various literatures—as set out in what follows—and this has the benefit of throwing up some inconsistencies and gaps that invite further research. The contrasts between the research done within different disciplines and fields of study provoke many questions about the organisation of knowledge. The first body of literature to consider is a negative case. The collecting, processing and trading of trepang all involve the sea and have thus been open to the view of those who also come and go in ships. Moreover, trepang has only rarely been for the consumption of those who collect and process it, but is usually for trade; there is money in trepang and that drew the interest of observers. -

Learning Through Country: Competing Knowledge Systems and Place Based Pedagogy’

'Learning through Country: Competing knowledge systems and place based pedagogy’ William Patrick Fogarty 2010 'Learning through Country: Competing knowledge systems and place based pedagogy’ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University William Patrick Fogarty September 2010 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, William Patrick Fogarty, declare that this thesis contains only my original work except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. This thesis contains an extract from a jointly authored paper (Fordham et al. 2010) which I made an equal contribution to and is used here with the express permission of the other authors. This thesis does not exceed 100,000 words in length, exclusive of footnotes, tables, figures and appendices. Signature:………………………………………………………… Date:……………………… Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND PHOTOGRAPHS..................................................................III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………………V DEDICATION .................................................................................................................................... VII ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... VIII LIST OF ACRONYMS.........................................................................................................................X CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHOD ..............................................................................1 -

Northern Territory) Act 1976

Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 No. 191, 1976 Compilation No. 41 Compilation date: 4 April 2019 Includes amendments up to: Act No. 27, 2019 Registered: 15 April 2019 Prepared by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel, Canberra Authorised Version C2019C00143 registered 15/04/2019 About this compilation This compilation This is a compilation of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 that shows the text of the law as amended and in force on 4 April 2019 (the compilation date). The notes at the end of this compilation (the endnotes) include information about amending laws and the amendment history of provisions of the compiled law. Uncommenced amendments The effect of uncommenced amendments is not shown in the text of the compiled law. Any uncommenced amendments affecting the law are accessible on the Legislation Register (www.legislation.gov.au). The details of amendments made up to, but not commenced at, the compilation date are underlined in the endnotes. For more information on any uncommenced amendments, see the series page on the Legislation Register for the compiled law. Application, saving and transitional provisions for provisions and amendments If the operation of a provision or amendment of the compiled law is affected by an application, saving or transitional provision that is not included in this compilation, details are included in the endnotes. Editorial changes For more information about any editorial changes made in this compilation, see the endnotes. Modifications If the compiled law is modified by another law, the compiled law operates as modified but the modification does not amend the text of the law. -

The Archaeology of Sulawesi Current Research on the Pleistocene to the Historic Period

terra australis 48 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern Volume 28: New Directions in Archaeological Science. New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) A. Fairbairn, S. O’Connor and B. Marwick (2008) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Volume 29: Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. G. Clark, F. Leach Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and and S. O’Connor (2008) Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 30: Archaeological Science Under a Microscope: Studies in Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Residue and Ancient DNA Analysis in Honour of Thomas H. Loy. M. Haslam, G. Robertson, A. Crowther, S. Nugent Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) and L. Kirkwood (2009) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology Volume 31: The Early Prehistory of Fiji. G. Clark and in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter A. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 21

Aboriginal History Volume twenty-one 1997 Aboriginal History Incorporated The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Secretary), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), Neil Andrews, Richard Baker, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Humes, Ian Keen, David Johnston, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Diane Smith, Elspeth Young. Correspondents Jeremy Beckett, Valerie Chapman, Ian Clark, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Campbell Macknight, Ewan Morris, John Mulvaney, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia will be welcomed. Issues include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Editors 1997 Rob Paton and Di Smith, Editors, Luise Hercus, Review Editor and Ian Howie Willis, Managing Editor. Aboriginal History Monograph Series Published occasionally, the monographs present longer discussions or a series of articles on single subjects of contemporary interest. Previous monograph titles are D. Barwick, M. Mace and T. Stannage (eds), Handbook of Aboriginal and Islander History; Diane Bell and Pam Ditton, Law: the old the nexo; Peter Sutton, Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia; Link-Up (NSW) and Tikka Wilson, In the Best Interest of the Child? Stolen children: Aboriginal pain/white shame, Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, History in Portraits: biographies of nineteenth century South Australian Aboriginal people. -

Catalogue 75 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS Visit Us at the Following Book Fairs

Catalogue 75 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS Visit us at the following book fairs: San Francisco Antiquarian Book, Print & Paper Fair 2 - 3 February 2018 California International Antiquarian Book Fair 9 - 11 February 2018 New York International Antiquarian Book Fair 8 - 11 March 2018 Tokyo International Antiquarian Book Fair 23 - 25 March 2018 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS 720 High Street Armadale Melbourne VIC 3143 Australia +61 3 9066 0200 [email protected] To add your details to our email list for monthly New Acquisitions, visit douglasstewart.com.au © Douglas Stewart Fine Books 2018 Items in this catalogue are priced in US Dollars Front cover p. 37 (#17095). Title page p. 66 (#17314). Back cover p. 14 (#16533). Catalogue 75 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS MELBOURNE • AUSTRALIA 2 McGovern, Melvin P. 1. Specimen pages of Korean movable types. Collected & described by Melvin P. McGovern. Los Angeles : Dawson’s Book Shop, 1966. Colophon: ‘Of this edition, three hundred copies have been printed for sale. Of these, ninety- five copies comprise the Primary Edition and are numbered from I to XCV. The remaining copies are numbered from 96 through 300. This copy is number [in manuscript] A, out of series (Tuttle) / For Mr. & Mrs Charles Tuttle who have heard much & seen nothing these five years. Peter Brogren‘. Folio, original quarter white cloth over embossed handmade paper covered boards, frontispiece, pp 73, with 22 mounted specimen leaves from 15th-19th centuries, identified in Korean as well as in English; bibliography; housed in a cloth slipcase; a fine presentation copy from the book’s printer, Peter Brogren of The Voyagers’ Press, Tokyo, produced out of series for the publisher and bookseller Charles E.