Download Date 28/09/2021 05:31:59

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wave Data Recording Program

Wave data recording program Weipa Region 1978–2004 Coastal Sciences data report No. W2004.5 ISSN 1449–7611 Abstract This report provides summaries of primary analysis of wave data recorded in water depths of approximately 5.2m relative to lowest astronomical tide, 10km west of Evans Landing in Albatross Bay, west of Weipa. Data was recorded using a Datawell Waverider buoy, and covers the periods from 22 December, 1978 to 31 January, 2004. The data was divided into seasonal groupings for analysis. No estimations of wave direction data have been provided. This report has been prepared by the EPA’s Coastal Sciences Unit, Environmental Sciences Division. The EPA acknowledges the following team members who contributed their time and effort to the preparation of this report: John Mohoupt; Vince Cunningham; Gary Hart; Jeff Shortell; Daniel Conwell; Colin Newport; Darren Hanis; Martin Hansen; Jim Waldron and Emily Christoffels. Wave data recording program Weipa Region 1978–2004 Disclaimer While reasonable care and attention have been exercised in the collection, processing and compilation of the wave data included in this report, the Coastal Sciences Unit does not guarantee the accuracy and reliability of this information in any way. The Environmental Protection Agency accepts no responsibility for the use of this information in any way. Environmental Protection Agency PO Box 15155 CITY EAST QLD 4002. Copyright Copyright © Queensland Government 2004. Copyright protects this publication. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this report can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without having prior written permission. -

Fishing the Tiwi Islands Welcome to Our Islands

FISHING THE TIWI ISLANDS WELCOME TO OUR ISLANDS The Tiwi Islands are made up of Melville and Bathurst Islands and numerous smaller, adjacent islands. The Vernon Islands also form part of the Tiwi estate. The Tiwi Traditional Owners and custodians of the area welcome you to our islands and ask that you respect and recognise the cultural importance of our land and waters. CODE OF Conduct RESPect THE RIGHts OF TRADITIONAL OWNERS. • Understand and observe all fishing regulations and no fishing zones. Report illegal fishing activities to the FISHWATCH hotline 1800 891 136 or the Tiwi Land Council HQ at Pickataramoor - 08 8970 9373. • Take no more fish than your immediate needs and carefully return excess or unwanted fish into the water unharmed. • Be courteous to all water users and those who belong to local Tiwi communities. • Respect Tiwi cultural ceremonies. This may mean that a particular area is temporarily closed to access. • Do not land ashore without first obtaining a separate Aboriginal land permit, from the Tiwi Land Council and abide by alcohol restrictions for the area. • Respect sacred sites and do not enter any part of the waters containing identified sacred sites unless specifically permitted to do so by the Tiwi Land Council. • Do not clean or dispose of fish within the vicinity of a community. • Prevent pollution and protect wildlife by removing rubbish and dispose of correctly to avoid potentially entrapping birds and other aquatic creatures. TIWI AND VERNON ISLANDS zones PERMIT FREE access The Tiwi have agreed to provide permit free access to the intertidal waters of the Tiwi and the Vernon Islands in the areas as outlined in the attached map. -

Natural Values and Resource Use in the Limmen Bight

NATURAL VALUES AND RESOURCE USE IN THE LIMMEN BIGHT REGION © Australian Marine Conservation Society, January 2019 Australian Marine Conservation Society Phone: +61 (07) 3846 6777 Freecall: 1800 066 299 Email: [email protected] PO Box 5815 West End QLD 4101 Keep Top End Coasts Healthy Alliance Keep Top End Coasts Healthy is an alliance of environment groups including the Australian Marine Conservation Society, the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Environment Centre of the Northern Territory. Authors: Chris Smyth and Joel Turner, Centre for Conservation Geography Printing: Printed on 100% recycled paper by IMAGE OFFSET, Darwin. Maps: Centre for Conservation Geography This report is an independent research paper prepared by the Centre for Conservation Geography commissioned by, and for the exclusive use of, the Keep Top End Coasts Healthy (KTECH) alliance. The report must only be used by KTECH, or with the explicit permission of KTECH. The matters covered in the report are those agreed to between KTECH and the authors. The report does not purport to consider exhaustively all values of the Limmen Bight region. The authors do not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation, compensatory, direct, indirect, or consequential damages and claims of third parties that may be caused directly or indirectly through the use of, reliance upon or interpretation of the contents of the report. Cover photos: Main - Limmen River. Photo: David Hancock Inset (L-R): Green Turtle, Recreational fishing is an important leisure activity in -

A Diagnostic Study of the Intensity of Three Tropical Cyclones in the Australian Region

22 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 138 A Diagnostic Study of the Intensity of Three Tropical Cyclones in the Australian Region. Part II: An Analytic Method for Determining the Time Variation of the Intensity of a Tropical Cyclone* FRANCE LAJOIE AND KEVIN WALSH School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia (Manuscript received 20 November 2008, in final form 14 May 2009) ABSTRACT The observed features discussed in Part I of this paper, regarding the intensification and dissipation of Tropical Cyclone Kathy, have been integrated in a simple mathematical model that can produce a reliable 15– 30-h forecast of (i) the central surface pressure of a tropical cyclone, (ii) the sustained maximum surface wind and gust around the cyclone, (iii) the radial distribution of the sustained mean surface wind along different directions, and (iv) the time variation of the three intensity parameters previously mentioned. For three tropical cyclones in the Australian region that have some reliable ground truth data, the computed central surface pressure, the predicted maximum mean surface wind, and maximum gust were, respectively, within 63 hPa and 62ms21 of the observations. Since the model is only based on the circulation in the boundary layer and on the variation of the cloud structure in and around the cyclone, its accuracy strongly suggests that (i) the maximum wind is partly dependent on the large-scale environmental circulation within the boundary layer and partly on the size of the radius of maximum wind and (ii) that all factors that contribute one way or another to the intensity of a tropical cyclone act together to control the size of the eye radius and the central surface pressure. -

5 Potential Impacts and Mitigation – Water Quality

5 POTENTIAL IMPACTS AND MITIGATION – WATER QUALITY The approach adopted for this study to evaluate potential water quality impacts associated with the proposed discharge relied on the application and interpretation of calibrated far-field, two-dimensional hydrodynamic (HD) and advection dispersion (AD) modelling tool built using MIKE21. This modelling was supported, guided and informed by a range of data and other relevant information. These data, the work conducted, and key findings are presented below. 5.1 Numerical Modelling Numerical modelling was used to simulate the transport, dilution and dispersion of the proposed discharge at Gunn Point and surrounding waters. The proposed discharge was modelled (see Appendix A) as a conservative tracer. This allows the dilution and dispersion of the effluent to be understood. The numerical modelling, and therefore the modelled tracer concentrations, can be considered conservative for the following reasons: Biological and physical processes such as the deposition of particulate material or the take up of bioavailable nutrients or absorption by sediments and algal mats (microphytobenthos) growing on the sediments of the significant intertidal areas in and around Shoal Bay are not included in the modelling. Three-dimensional turbulent dispersion associated with wave action has not been included in the modelling. Because the model was very computationally demanding, all scenarios were undertaken in 2D. However, during the model calibration and sensitivity testing, 3D simulations were carried out to confirm the mixing processes were resolved appropriately. The strong tidal currents and shallow water mean the site is well mixed, and the 3D modelling did not provide significantly different results. 5.1.1 Simulation Scenarios The model was run for two separate years: June 2005 – May 2006 inclusive May 2016 to April 2016 inclusive Whilst tropical conditions are highly variable, 2005-2006 was considered a ‘typical’ wet season, and 2016- 2017 a season with higher than average rainfall. -

Project 4.13 Assessing the Gulf of Carpentaria Mangrove Dieback

Project 4.13 Assessing the Gulf of Carpentaria Mangrove Dieback Project Summary In early 2016, extensive dieback of mangrove forests was recorded along the southern and western Gulf of Carpentaria coastline. Landsat analysis suggests that more than 8,000 hectares of mangrove forest suffered dieback over a relatively short and synchronous time period around November 2015 along a >2,000km wide front from Pormpuraaw in the east (Queensland) to Rose River in the west (Northern Territory). Initial field visits to a limited range of affected sites suggest that a relatively low percentage of trees have recovered and most are dying or dead. This is the largest event of natural dieback of mangroves ever recorded in the world. Problem Across the whole dieback area, there is not for any location, a current formal assessment of the condition of affected forests and what proportion are recovering. Of the affected forests, most are shoreline mangroves, whose death would leave the coastal shoreline exposed to erosion and storm surge effects which may cause even greater and more serious geomorphic and ecological disturbance to this coastline. Biodiversity is likely to have been significantly impacted. Recent field observations showed the epibiont communities that reside upon the trunks and aerial roots of the mangroves have been shed as these structures die and decay, and leaf litter supplies, an important source of food for fisheries production, has significantly decreased. How Research Addresses Problem This project will survey, describe and analyse the dieback across its range. Examination of the patterns of dieback will provide significant insights into the causative factors, what species are in what locations, and in what tidal elevations were species most impacted, and where it was most pronounced. -

Feather Stars Page 2

Autumn 2020 VOLUME 21 Supporter Newsletter CREATURE FEATURE Feather Stars Page 2 Imagine: Carbon Threatened Protecting Free Future Species: Sharks Ningaloo Page 4 Page 6-7 Page 12 With Thanks to YOU Humpback Whales Humpback On the cover: Feather star (Crinoid). This page: Feather Star, Coral Sea © Steve Parish. Sea © Steve Coral Star, This page: Feather (Crinoid). star Feather On the cover: Creature Feature Protecting amazing sea life thanks to you... Reflecting On Summer 2019/20 Together we fight for healthy oceans and planet… The ocean is our planet’s Feather stars life support system. are plant-like marine animals Crisis Southern Ocean Fabulous Feather Stars Summer Whales Win Feather stars look like feathery plants, but they Australia is uniquely vulnerable to the This summer was a historic time for the whales are in fact marine animals. impacts of global warming. of the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. These creatures hide in plain sight among bright This past summer we have experienced For more than a century, whaling fleets have corals and anemones. extreme weather events across our beautiful hunted the Southern Oceans each summer, They get their name from their long branched country, which climate scientists have warned but now - at long last - Antarctic whales are arms, which have a feathery appearance. about for decades. While our land has free from the harpoons. Feather stars can have as many as 40 arms, been ravaged by fires and droughts, our Thanks to you, and whale lovers around our which they wave around catching small food oceans are suffering from escalating marine blue planet taking action, Japan’s whaling fleet particles that float by. -

Northern Territory) Act 1976

Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 No. 191, 1976 Compilation No. 41 Compilation date: 4 April 2019 Includes amendments up to: Act No. 27, 2019 Registered: 15 April 2019 Prepared by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel, Canberra Authorised Version C2019C00143 registered 15/04/2019 About this compilation This compilation This is a compilation of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 that shows the text of the law as amended and in force on 4 April 2019 (the compilation date). The notes at the end of this compilation (the endnotes) include information about amending laws and the amendment history of provisions of the compiled law. Uncommenced amendments The effect of uncommenced amendments is not shown in the text of the compiled law. Any uncommenced amendments affecting the law are accessible on the Legislation Register (www.legislation.gov.au). The details of amendments made up to, but not commenced at, the compilation date are underlined in the endnotes. For more information on any uncommenced amendments, see the series page on the Legislation Register for the compiled law. Application, saving and transitional provisions for provisions and amendments If the operation of a provision or amendment of the compiled law is affected by an application, saving or transitional provision that is not included in this compilation, details are included in the endnotes. Editorial changes For more information about any editorial changes made in this compilation, see the endnotes. Modifications If the compiled law is modified by another law, the compiled law operates as modified but the modification does not amend the text of the law. -

Public Environmental Report

Darwin 10 MTPA LNG Facility Public Environmental Report March 2002 Darwin 10 MTPA LNG Facility Public Environmental Report March 2002 Prepared for Phillips Petroleum Company Australia Pty Ltd Level 1, HPPL House 28-42 Ventnor Avenue West Perth WA 6005 Australia by URS Australia Pty Ltd Level 3, Hyatt Centre 20 Terrace Road East Perth WA 6004 Australia 12 March 2002 Reference: 00533-244-562 / R841 / PER Darwin LNG Plant Phillips Petroleum Company Australia Pty Ltd ABN 86 092 288 376 Public Environmental Report PUBLIC COMMENT INVITED Phillips Petroleum Company Australia Pty Ltd, a subsidiary of Phillips Petroleum Company, proposes the construction and operation of an expanded two-train Liquefied Natural Gas facility with a maximum design capacity of 10 million tonnes per annum (MTPA). The facility will be located at Wickham Point on the Middle Arm Peninsula adjacent to Darwin Harbour near Darwin, NT. The proposed project will include gas liquefication, storage and marine loading facilities and a dedicated fleet of ships to transport LNG product. A subsea pipeline supplying natural gas from the Bayu-Undan field to Wickham Point and a similar, but smaller 3 MTPA LNG plant were the subject of a detailed Environmental Impact Assessment process and received approval from Commonwealth and Northern Territory Environment Ministers during 1998. The environmental assessment of the expanded LNG facility is being conducted at the Public Environmental Report (PER) level of the Northern Territory Environmental Assessment Act and the Commonwealth Environmental Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act. The draft PER describes the expanded LNG facility with particular emphasis on its differences from the previously approved LNG facility and addresses the potential environmental impacts and mitigation measures associated with the project. -

Flood Watch Areas Arnhem Coastal Rivers Northern Territory River Basin No

Flood Watch Areas Arnhem Coastal Rivers Northern Territory River Basin No. Blyth River 15 Buckingham River 17 East Alligator River 12 Goomadeer River 13 A r a f u r a S e a Goyder River 16 North West Coastal Rivers Liverpool River 14 T i m o r S e a River Basin No. Adelaide River 4 below Adelaide River Town Arnhem Croker Coastal Daly River above Douglas River 10 Melville Island Rivers Finniss River 2 Island Marchinbar Katherine River 11 Milikapiti ! Island Lower Daly River 9 1 Elcho ! Carpentaria Coastal Rivers Mary River 5 1 Island Bathurst Nguiu Maningrida Galiwinku River Basin No. Island 12 ! ! Moyle River 8 ! Nhulunbuy 13 Milingimbi ! Yirrkala ! Calvert River 31 South Alligator River 7 DARWIN ! ! Howard " Oenpelli Ramingining Groote Eylandt 23 Tiwi Islands 1 2 Island 17 North West 6 ! 14 Koolatong River 21 Jabiru Upper Adelaide River 3 Coastal 15 Batchelor 4 Limmen Bight River 27 Wildman River 6 Rivers ! 16 7 21 McArthur River 29 3 5 ! Bickerton Robinson River 30 Island Daly River ! Groote Roper River 25 ! ! Bonaparte Coastal Rivers Bonaparte 22 Alyangula Eylandt Rosie River 28 Pine 11 ! 9 Creek Angurugu River Basin No. Coastal 8 Towns River 26 ! ! Kalumburu Rivers Numbulwar Fitzmaurice River 18 ! Walker River 22 Katherine 25 Upper Victoria River 20 24 Ngukurr 23 Waterhouse River 24 18 ! Victoria River below Kalkarindji 19 10 Carpentaria G u l f 26 Coastal Rivers ! o f ! Wyndham Vanderlin C a r p e n t a r i a ! 28 Kununurra West Island Island 27 ! Borroloola 41 Mount 19 Barnett Mornington ! ! Dunmarra Island Warmun 30 (Turkey 32 Creek) ! 29 Bentinck 39 Island Kalkarindji 31 ! Elliott ! ! Karumba ! 20 ! Normanton Doomadgee Burketown Fitzroy ! Crossing Renner ! Halls Creek ! Springs ! ! Lajamanu 41 Larrawa ! Warrego Barkly ! 40 33 Homestead QLD ! Roadhouse Tennant ! Balgo Creek WA ! Hill Camooweal ! 34 Mount Isa Cloncurry ! ! ! Flood Watch Area No. -

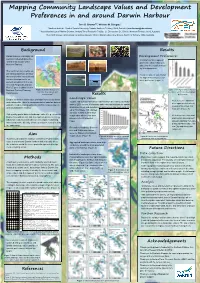

New PPGIS Research Identifies Landscape Values and Development

Mapping Community Landscape Values and Development Preferences in and around Darwin Harbour Tom D. Brewera,b, Michael M. Douglasc a Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0909, Australia ([email protected]). b Australian Institute of Marine Science, Arafura Timor Research Facility, 23 Ellengowan Dr., Brinkin, Northern Territory, 0810, Australia. a Research Institute of Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0909, Australia. Background Results Darwin Harbour is a highly val- Development Preferences ued and contested place; the A total of 647 development ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the preference sticker dots were Northern Territory. placed on the supplied maps by 80 respondents. The catchment is currently ex- periencing significant develop- ‘No development’ was, by far, ment and further industrial and the highest scoring develop- tourism development is ex- ment preference (Figure 7). pected, as outlined in the cur- rent draft Regional Land Use Plan1 (Figure 1) tabled by the Northern Territory Planning Figure 1. Darwin Harbour sec- Figure 7. Average scores (of a possi- tion of the development plan ble 100) for each of the development Commission. overview map1 Results preferences. Landscape Values Despite its obvious iconic value and significant use by locals Preference for industrial and visitors alike, there is no representative baseline data on To date 136 surveys have been returned from the mail-out question- development is clustered what the residents living within the catchment most value in naire to 2000 homes. Preliminary data entry and analysis for spatial around Palmerston and and around Darwin Harbour. landscape values and development preferences has been conduct- East Arm (Figure 8). -

Dugongs Information Valid As of June 2014

Dugongs Information valid as of June 2014 mortality from boat strike, or chronic indirect Summary pressures on seagrass meadows resulting from declining water quality. Boat strike is more likely to Diversity occur in areas adjacent to population centres and Single species – dugong (Dugong dugon, last entrances to busy ports that may also be important remaining species of the family Dugongidae; Order: foraging grounds for dugongs. These areas might Sirenia) also be exposed to declining water quality from catchment run-off and habitat degradation due to Susceptibility increased coastal and marine development. The Life-history traits that predispose dugongs to threats combination of these pressures over time can cause include being long-lived with low reproductive impacts on dugong health, the availability or health of potential, delayed sexual maturity, high female their food (primarily seagrasses) and eventually the investment in each offspring, migratory (they range status of the population. across international boundaries into areas where they Applied or assessed separately, these pressures may are highly targeted and less protected), and a reliance not seem significant, but research indicates the on inshore habitats which increases their exposure to combined and cumulative impact of these major human-related and land-based threats. pressures present significant concerns for the conservation and management of dugongs in the Major pressures World Heritage Area. Impacts of greatest significance to dugongs south of Cooktown are habitat